Ed. Note: Vanessa Mongey’s article, “Protecting Foreigners: The Refugee Crisis on the Belize-Yucatán Border, 1841-1871,” appears in the February, 2021 issue of Law and History Review (vol. 39, no. 1). In conversation with The Docket, Dr. Mongey reflected on several questions that lie at the heart of her article, as well as her other projects.

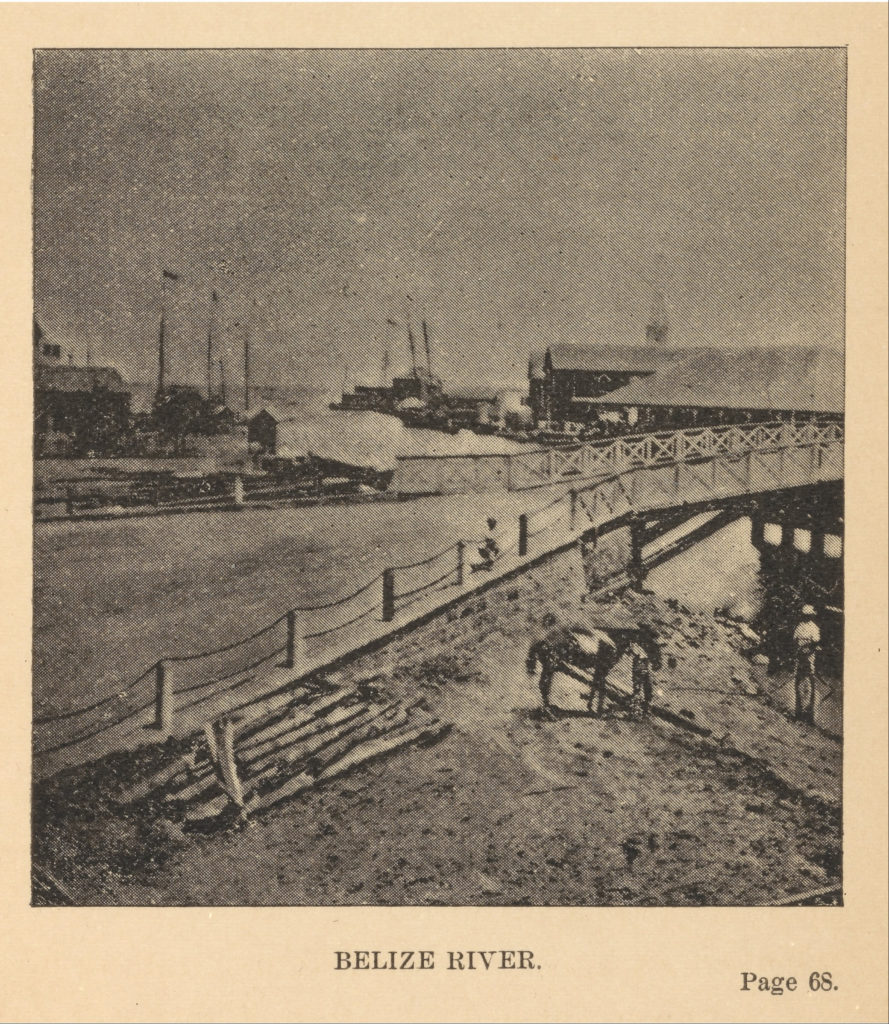

The Docket [TD]: When people think of the British Empire, or even the British empire in the Americas, they rarely think of Belize (or British Honduras as it was known then). The article starts with thousands of people from the Mexican region of Yucatáncrossing the border in 1847. This movement of peoples eventually doubled the population of Belize. Can you tell us why so many Mexicans moved to Belize and why they played such a role in shaping the destiny of Belize and the British Empire?

Vanessa Mongey [VM]: Starting in 1847, an armed conflict broke out among different groups in the Yucatán Peninsula. The so-called Caste War was a complex conflict that devastated the region for over fifty years. At the time, Belize had an ambiguous status within the British Empire. It was a settlement, not a formal colony, and white settlers were attached to their autonomy. Belize was also adjusting to the abolition of slavery and the place of free Afro-Belizeans. Although Belize is often neglected by the scholarship on both Latin America and the British World, my article argues that the response to the refugee crisis in Belize provides valuable insight into how ideas around protection and asylum were interpreted and manipulated in the Atlantic World.

Asylum has a long lineage in Britain. In 19th century British expansionist liberal ideology especially, the label of refugee, although nowhere defined in law, was recognized by the public as a special status. The refugee was a –usually male—foreigner who had suffered persecutions or abuse and sought protection on British soil. The Caste War became an opportunity to reshape the interface between the metropole and Belize. Local authorities were unable to police the borders and stop these newcomers. They quickly realized the economic benefits that these refugees brought with them: they grew valuable crops such as coffee, tobacco, and sugarcane and unlocked the agricultural potential of the settlement. Through trial and error, authorities in Belize framed this movement of peoples into a “refugee crisis” and into a humanitarian discourse that eventually enabled them to secure British sovereignty over the territory (and the people living on it) and Belize’s transition to a colony.

TD: This seems like an exciting moment for scholars interested in the intersections among legal history, humanitarianism, and imperialism. Are there scholars or scholarly works that you have particularly admired in recent years?

VM: Several scholars have shown how the language around protection often served to fortify imperial claims and reinforced the legitimacy of British rule. I think of Luke Glanville, Lauren Benton, Lisa Ford, and Bronwen Everill in particular. Other scholars, such as Caroline Shaw, Bernard Porter, and Thomas C. Jones, have shown the complex history behind Britain’s ‘”right of asylum.”

Although Belize is often absent from Latin American studies, what happened there tie into conflicts between local authorities and other groups, the ambiguous place of people of African and indigenous decent that you see in many Latin american countries after independence. Some fabulous scholars have enhanced our understanding of Belize and the fluidity of racial and ethnic categories, notably O. Nigel Bolland, Elisabeth Cunin, Odile Hoffman, and recently Rajeshwari Dutt and her book Empire on Edge: The British Struggle for Order in Belize during Yucatán’s Caste War.

What made Belize unique was that the people who escaped the conflicts in Yucatán did not fit the usual image of refugees: many of them were neither white nor male. They received unstable labels such as “Indian,” “Maya,” “Hispanic,” or “Spaniard.” As I show in the article, the label of refugee was equally unstable: it was not only a way to showcase British liberal and humanitarian values, but also a way to control these newcomers. The article explains how Belize put in place a system that disenfranchised the refugees. The discourse around asylum and refugees in Belize consolidated white settler colonialism and expanded imperial power. You can see a similar process in different parts of the British empire and other empires and countries as well.

TD: Chief Justice Robert Temple takes center stage in Belize’s treatment of refugees from Yucatán. Can you tell us more about him?

VM: If Belize is often under-represented in studies of the British empire and Latin America, the same is true of Chief Justice Robert Temple in studies of Belize or British legal history. Temple arrived in Belize a few years before the outbreak of the Caste War and struggled with the settler elite. A small number of wealthy white inhabitants, often in the mahogany business, was not keen on formal British rule. Temple therefore used the movement of peoples from Yucatán to strengthen English law in the settlement and to push for colonial status. His Supreme Court decisions redefined the legal and jurisdictional landscape of the settlement. He drew on legal theorists Hugo Grotius, Samuel von Pufendorf, and Matthew Hale. He saw this refugee crisis as a litmus test for Belize’s status as a “civilized” state and its place in the British empire.

Temple referred to Belize as a “city of refuge” where virtuous and persecuted refugees benefited from a strong and liberal government, leaving chaos behind. He framed Belize as a place of law and order in the midst of a disorderly Central America. The fact that many of these refugees were Maya also helped him as a pre-Hispanic craze was in full swing in the Atlantic World: local authorities, including Temple, donated Maya antiquities to the British Museum. I’ve been trying to track these artifacts.

This image of Belize as a city of refuge was a double-edged sword. Belize had a rotating cast of superintendent in the 19thcentury: one of them argued that Belize would turn into a sanctuary for criminals, or as he put it, “scourings of the populations of neigboring countries, including some of the greatest ruffians the world can produce.” But whether it was to prove Belize’s status as a humanitarian haven or to protect Belize from these foreign ruffians, both the superintendent and the chief justice demanded stronger support and recognition from Britain.

Yucatecans were a solution to the economic needs of the settlement. Belize needed foreigners to thrive. Temple reached out to U.S. African Americans and promised them that Belize was a land of equality, justice and opportunity. When this scheme didn’t work out, he turned to white U.S. Southerners. Embroiled in various scandals, Temple’s commission was revoked in 1861: he was not there when Belize officially became a British colony in 1863 and a Crown colony in 1870.

TD: In the conclusion of your article, you write that after Belize transitioned to a colony: “the discourse around protection became a way to control and exploit the refugees,” and you mention the Extradition Act of 1870 and aliens Act in 1905 as part of global trend to legislate for immigration restrictions. Can you say a bit more about this marginalization and how the refugee crisis in Belize speaks to the present?

VM: If Chief Justice Temple managed to extend English law and jurisdiction to all those living in Belize, regardless of their race or place of birth, most native or foreign-born non-white inhabitants were excluded from landownership and political representation. They were not allowed to own land, they could only rent or become wage laborers. Yucatecans living in Belize became increasingly suspicious. Again, this was part of a broader movement in the British Atlantic world with many advocating for a distinction between honest refugees and violent criminals, leading to the Extradition Act in 1870 and the Aliens Act in 1905.

Refugees had to show –and perform—their appreciation to the liberal British government. Any act or behavior that was perceived as ungrateful was punished. It echoes what is happening today. The anthropologist Didier Fassin has argued that the current debate about refugees has shifted from a legal question of rights to a moral question of favor or as he calls it “[s]elective humanitarianism.’” Dina Nayeri explains this process in detail in Ungrateful Refugee, based on her Guardian article.

Many governments, including the British government, portray refugees as forces of chaos and criminals. Former Prime Minister David Cameron used the phrase “swarm of people” to describe refugees in the grim camps of Calais. The current government has just removed protective measures for refugee children. Of course, unlike 19th century Belize where foreign-born inhabitants were a majority, asylum seekers are a very small percentage of overall migrants to the U.K. and an even smaller percentage of the overall population. And yet, they are the objects of disproportionate fears and anxieties.

TD: Your book, Rogue Revolutionaries: The Fight for Legitimacy in the Greater Caribbean, recently won the Gilbert Chinard Prize by the Society for French Historical Studies. Congratulations! Could you tell us more about your current research projects?

VM: I created a digital companion with a lot of extra resources if people want to use it alongside the book itself. The site is in English, French and Spanish.

I’m currently working on international travel in the North Atlantic world (1770-1870) and the right to travel –especially for Afro-descendants in the French-speaking world. While the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights guarantees the right to freedom of movement, no one questions today that individuals categorized as suspicious, namely criminals or terrorists, may be restricted or even barred from traveling freely. I would like to trace the origins of these debates and how freedom of movement became a testing ground for ideas about nationality, race, and gender.

I also started a project called Paths Across Waters on Black British history in the North East of England. It follows the sailors, students, doctors, and musicians, who came to a region we do not often associate with migrants from the Caribbean and West Africa –unlike London or Liverpool, but that has a rich history of anti-racism and Pan-African activism in the pre-Windrush period. People can check my website to see the documents and essays I have put online.