Ed. Note: Catherine L. Fisk’s article, “‘People Crushed by Law Have No Hopes but from Power’: Free Speech and Protest in the 1940s,” appears in the February issue of Law and History Review (vol. 39, no. 1, February, 2021, pp. 173-204). Professor Fisk kindly took a few moments to reflect on her research and her new project on 20th century American labor lawyers. Our conversation is below.

The Docket [TD]: Your fascinating article walks readers through a kind of hidden history of the Hughes v. Superior Court case that dates back to 1950. Can you tell our readers how you got interested in this case and what led you to this idea for the article?

Catherine Fisk [CF]: I’ve been studying the history of legal restraints on labor activism between 1935 and 1990. While reading the 50-plus United States Supreme Court decisions from that period on picketing and labor protest, I was struck by the difference in how the Court treated (and still treats) civil rights picketing and boycotts as compared to labor picketing and boycotts. If labor activists picket or boycott, the law deems it coercive conduct that is prohibited by federal law and sometimes is subject to crushing damages liability. If civil rights activists engage in the same conduct, it is political speech that enjoys the highest level of protection under the First Amendment. But, as I show, Hughes treated them the same way. In trying to understand the context of the case, I began digging into the collaboration between civil rights activists and labor activists, such as the CIO’s famous organizing drive in the South (known as Operation Dixie), and the less well known collaborations between labor and civil rights radicals in California.

TD: Why do you think that legal historians haven’t understood the importance of Hughes in the trajectory of American legal history?

CF: There are many reasons. Some people have taken the reasoning of Hughes at face value and have treated it as a challenge to affirmative action, without digging into the story behind it. Part of the reason is that there hasn’t yet been a history of labor lawyers in the twentieth century (though I’m working on one, and Willy Forbath is working on another, with a different focus). Part of it is that the histories of the labor movement and the civil rights movement, such as Reuel Schiller’s, didn’t focus on this period and this fight.

TD: This seems like a particularly exciting moment for scholars interested in modern US labor history. Are there scholars or scholarly works in this field that you have particularly admired in recent years?

CF: Wow — that’s a hard question because there are decades worth of really superb work on labor history and labor law history, and I’m terrified that in identifying anyone I’ll accidently overlook someone. There are the greats whose works I read when I was starting out in the field — the works of Nelson Lichtenstein, David Montgomery, Chris Tomlins, Jim Pope, and Willy Forbath are among those that especially inspired and intimidated me. More recently, Laura Weinrib, Sophia Lee, and Reuel Schiller have written superb and broad-ranging books that shaped my thinking about the intersection of labor, free speech, and civil rights. And, among the recent books on more specific struggles, I admire Ahmed White on the Little Steel strike, and Donna Haverty-Stacke on the federal prosecutions of Minneapolis labor activists for alleged sedition under the Smith Act. Of legal scholars who’ve written about labor law and labor protest, there’s a long list of great people, but Cindy Estlund and Deborah Malamud, and more recently Ben Sachs and Kate Andrias, are scholars whom I particularly admire.

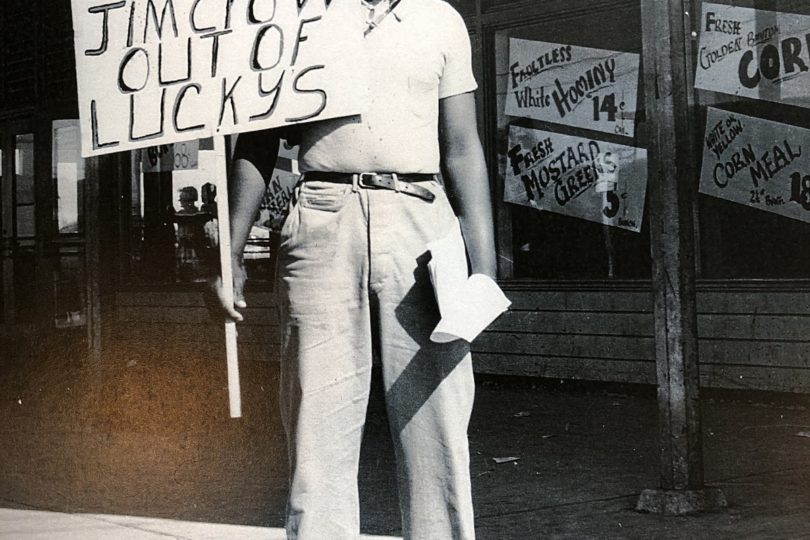

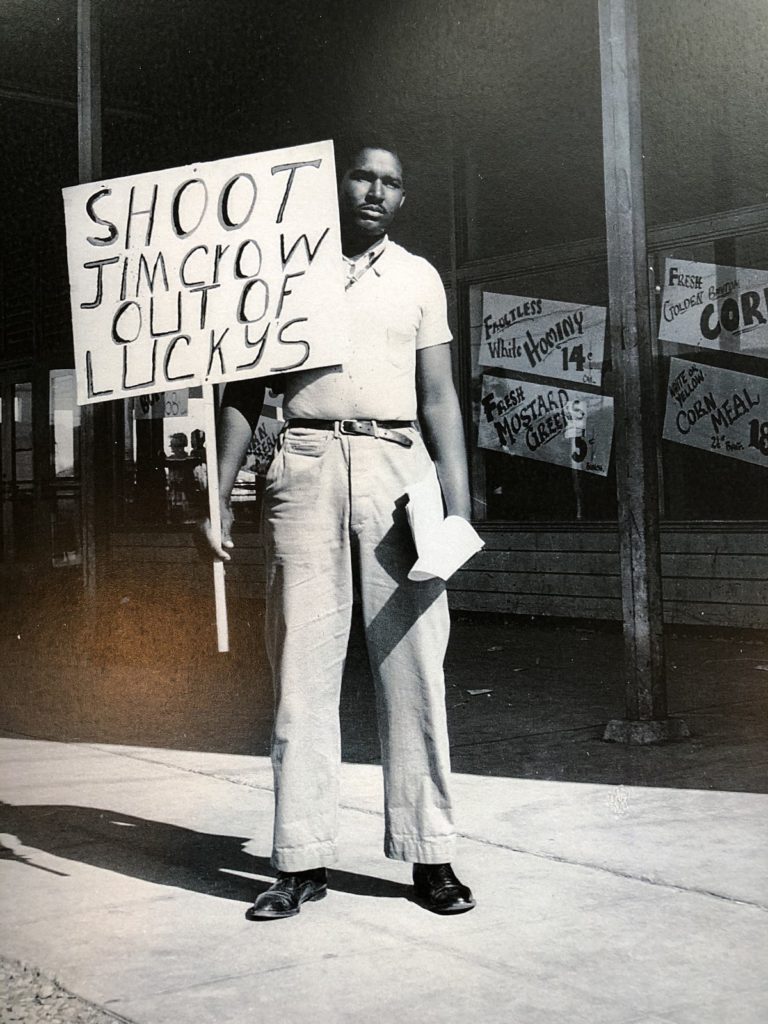

TD: The story of the Hughes case begins with the Lucky’s store on Canal Street in Richmond in 1947. In the article you explain what race discrimination looked like for African-American customers, and why Louis Richardson and John Hughes decided to take to the picket line. You also provide us with a startling image of a protestor holding a sign that reads, “Shoot Jim Crown Out of Lucky’s.” Can you walk us through what you know about this image, and perhaps any other details you learned about the protests outside the Lucky Story that gave rise to the case?

CF: For the photographs of the picket and the store, a hat tip to Rey Fuentes, my superb Berkeley Law research assistant in 2018, who went to the Richmond Museum of History and the California Historical Society hunting for the history of this case, and credit to the Richmond Museum of History which has the images in its collection. I don’t know who the man is holding the “Shoot Jim Crow Out of Lucky’s” picket sign, but it’s the protest in this case. I just don’t know how many other people, if any, were involved besides Hughes and Richardson.

TD: The U.S. Supreme Court takes center stage toward the middle of your article. One particularly fascinating story you recount is the Chicago dairy driver case, or Meadowmoor Dairies. In that case Justice Felix Frankfurter favored states ability to prevent violence over individual civil liberties, including free speech. Justices Frankfurter and Black have a little back and forth that will intrigue many of our readers. Can you explain a bit more about what happened here, and why Black chose to dissent in this case? Was this a turning point in how Black understood civil liberties?

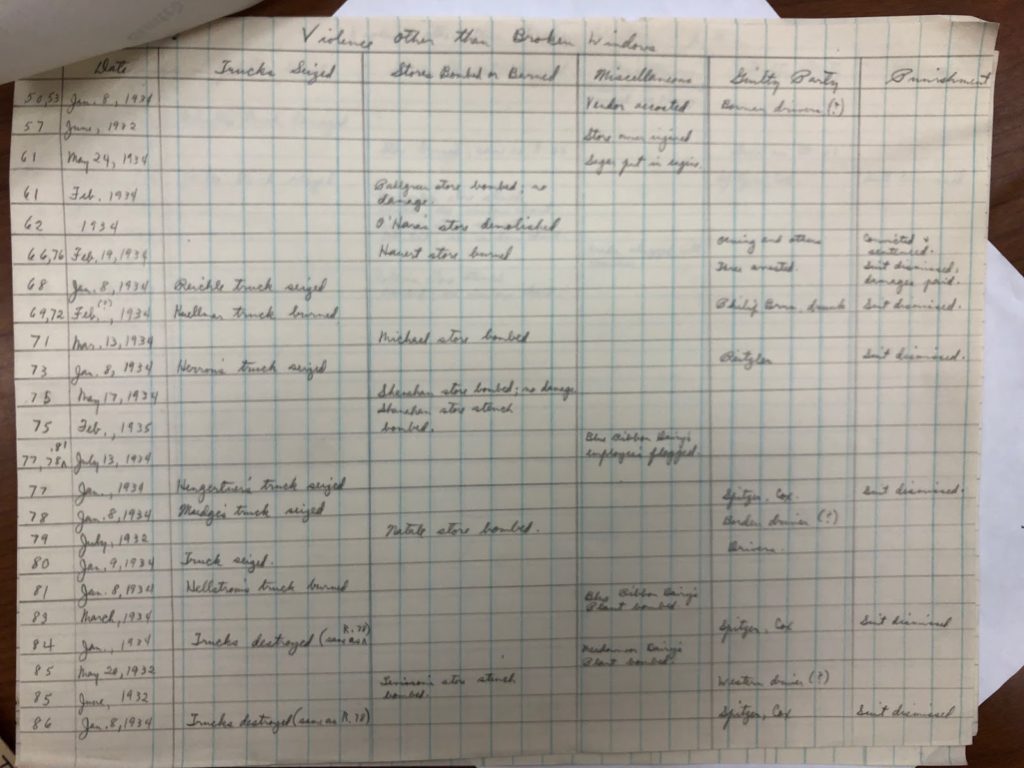

CF: In Meadowmoor, Justice Frankfurter began to move the Court away from treating labor picketing as speech protected by the First Amendment. Most cases citing Meadowmoor treat the facts and the holding of the case exactly as you did — states can enjoin picketing to prevent violence. But when I went to the Library of Congress to research the Supreme Court’s files on the labor protest cases, I discovered a very different story in Justice Black’s files on the Meadowmoor case. As Justice Black explains in his dissent, and as his notes exhaustively reveal, the violence in the Chicago dairy drivers’ strike was very far removed in time from the picketing that the court enjoined. Black saw the Court removing labor protest from the sphere of free speech and allowing state courts to do precisely what Frankfurter had excoriated in his 1930 book on labor injunctions — to issue sweeping injunctions against labor protest whenever a judge decided that somebody on a picket line might engage in violence or destroy property.

This image from Black’s notes shows how Black painstakingly scoured the record in the case to document incidents of property damage and how far removed they were from what the court enjoined. Black was still relatively new on the Court, and Frankfurter quite famously patronized him. I love the story of Black tweaking Frankfurter and gaining confidence to push back against Frankfurter’s efforts to eliminate constitutional protection for protest. Scholars of the mid-20th century Supreme Court are familiar with the bitter disagreements about civil liberties and civil rights that spilled over into personal nastiness among the justices in the late 1940s and 1950s. They were, many have said, like scorpions in a bottle. I hadn’t realized until I looked at the files of this case, that the rift between Black and Frankfurter was quite so stark in this case.

TD: In the conclusion of your article, you write: “Today’s labor and civil rights activists protest together and speak the same social justice language” of the social movement organizations and actors in the mid-twentieth-century US. “They follow the example of John Hughes and Louis Richardson, but not the case that bears their name.” This powerful conclusion does lead us to think a bit more about the state of labor politics in the present. Can you say a bit more about how the story of the case speaks to the present?

CF: I see two ways the story of Hughes speaks to the present. First, the discrimination and the violence directed at Black people persists, as does the Supreme Court’s indifference to it. The store employee shot Jackson for alleged shoplifting. The police do nothing to protect Jackson or any other customer from violence. When the community protested, company management say the employee was fired, which was a lie. When Hughes and Richardson then try to enlist community support in their efforts, then the courts suddenly perceive a threat to public order and enjoin the picketing calling for a boycott. Lucky’s lawyers portray an effort to remedy blatant race discrimination as an effort to demand racial quotas, and the Supreme Court agrees. Truly, it feels like nothing has changed in 70 years and that makes me angry.

The second way the case speaks to the present is that it reminds us that labor protest and civil rights protest are not two different things (contrary to the way the Supreme Court has treated them); they are the same thing. The organizing and activism that both preceded and followed the police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and so many others connects economic inequality and racial inequality. There is a great deal of worker activism now, such as demanding hazard pay for workers at high risk of contracting Covid-19, or demanding an increase in the minimum wage to $15 an hour and the right to unionize. Hope springs eternal that it will lead to sustained worker power across the economy.

TD: Many of our readers will be familiar with your previous scholarship, especially your books Working Knowledge: Employee Innovation and the Rise of Corporate Intellectual Property, 1800-1930 (2009) and Writing for Hire: Unions, Hollywood, and Madison Avenue (2016). Could you give our readers a quick look at your current research projects?

CF: This article is part of my current book project, which is still in its early stages. I’m writing about mid-20th century labor lawyers, and I’m especially interested in those that represented CIO unions or unions engaged in the kind of activism that courts aimed to restrain, as in Hughes. The lawyers who represented Hughes and Richardson are among the group I’m studying. These lawyers were drawn to the labor movement because they were activists at heart, and many of them faced retaliation from the FBI and the organized bar for representing radical clients. I’m trying to understand how they reconciled their desire to support the movement and activism with the increasingly repressive law after 1947. For example, in a recent article with Diana Reddy, Protection by Law, Repression by Law: Bringing Labor Back Into Law and Social Movement Studies, 70 Emory Law Journal 63 (2020), we dig into the history of the first major damages judgment against a union under the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 to understand what effect it had on the work of union lawyers.