Ed. Note. The following is an excerpt of Dr. Andreas Kuerten’s review of Ronit Y. Stahl’s Enlisting Faith: How the Military Chaplaincy Shaped Religion and State in Modern America, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017. Pp. x + 384. $41.00 hardcover (ISBN 9780674972155), which appears in Law and History Review 39, no. 1 (February, 2021), 215-17.

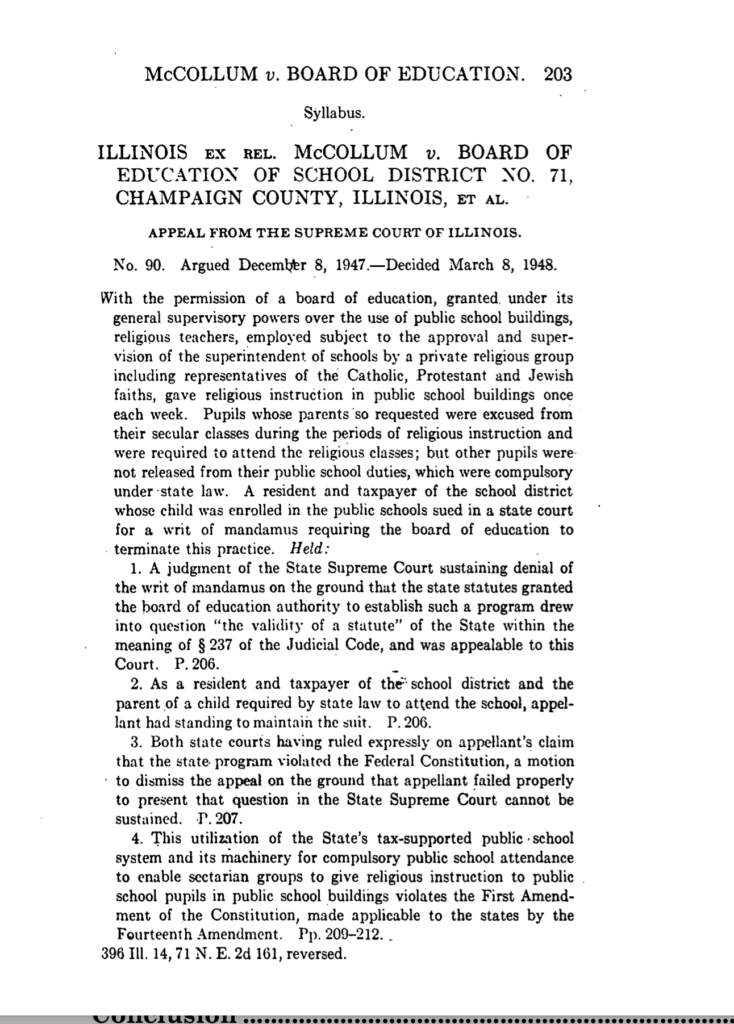

In its 1948 opinion in McCollum v. Board of Education, the U.S. Supreme Court famously stated that “the First Amendment [of the U.S. Constitution] rests upon the premise that both religion and government can best work to achieve their lofty aims if left free from the other within its respective sphere.” Courts have interpreted the passage as barring the government from endorsing religion, using religion for public aims, or inhibiting the free exercise of religion absent extenuating conditions. This separation of church and state has been dutifully policed by actors deploying the First Amendment to prevent either from encroaching too significantly on the other.

Nevertheless, as Ronit Stahl explores in her book Enlisting Faith, there exists a roughly century-old government religious corps that ostensibly flouts such a division. Through it, the government deploys religion “as a public interest” and strictly regulates religion and the conduct of religious professionals and, in turn, religious groups receive state recognition and their members become religious government officials (p. 7). This “constitutionally anomalous institution” is the military chaplaincy, which “manages a tremendous state infrastructure” dedicated to religion (p. 264). And, over the course of its crystallization and growth in the twentieth century, the chaplaincy “yoked religion to the state” and was a conduit through which the military influenced religion in America and religious groups influenced government (p. 265).

Across eight chapters and using several major twentieth-century conflicts and inter-conflict periods as temporal and developmental markers, Stahl elegantly and engagingly traces the history of the “bidirectional influence of religion and state” in the military chaplaincy and the evolution of this institution from World War I to the 1980s (p. 6). [….]

The main threads of Enlisting Faith are the development of a unique religious military contingent and ethos and the religious exchange that took place between the military and broader civil and civilian society over time. For its part, the military chaplaincy is as old as the republic. However, the scale of the Great War prompted the military to officially bring a previously “rudimentary and makeshift” enterprise under its ambit as a distinct officer corps through which “the state mobilized faith to sustain its martial goals” (pp. 9, 17). An organization and process emerged that molded religion to fit the narrow aims of the military, namely, the maintenance of good order and discipline and the fielding of effective fighting forces. This was achieved chiefly by eschewing “pernicious sectarianism” and emphasizing pluralism (p. 20). The armed forces cultivated what Stahl calls “moral monotheism”: “an imprecise yet productive religious worldview” stressing general faith, honorable conduct, and national belonging (p. 17). Religion became a tool for creating unity, boosting morale, encouraging proper behavior, and inculcating patriotism. Chaplains, for their part, were tasked with addressing the spiritual needs of all, regardless of creed, and, in large part, practiced a military-conceived and -shaped conception of religion based on ecumenical principles. Accordingly, “[o]ver the twentieth century, . . . [chaplains] built—in concrete policy and as figurative symbols—state-sponsored American religion” (p. 14). And through both deliberate and unmethodical interactions with civil and civilian society, “changes wrought through the chaplaincy traveled back home and permeated American life” (p. 9), including increased acceptance of minority religions and a view of religion emphasizing broadly acceptable moral imperatives over group differences.

Civil and civilian society, and religious groups and individuals therein in particular, influenced and used the chaplaincy as well. A prime example is the military’s approach to determining which religions were primary in or even part of the “moral monotheism” melting pot, as the “rhetoric of religious pluralism often outpaced reality” (p. 7). For much of the twentieth century, the military viewed religion and religious groups in severely circumscribed terms, deploying a tri-faith framework: Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish (in practice, African American was a fourth “religious” category for a substantial period of time). This only incrementally and inconsistently changed as diversity in the ranks increased and religious groups and individuals effortfully sought and obtained state recognition and accommodation. Stahl recounts Buddhists and Muslims striving for acknowledgement and chaplaincy commissions, Orthodox Christians and Mormons struggling to not simply be labeled Protestant, and Seventh-Day Adventists facing courts-martial seeking compromises to properly observe their Saturday Sabbath. These and other efforts steadily broadened the military conception of religion, elevated the standing of numerous religious groups in the military and America, and increased access to the chaplaincy and state power. [….]

If Enlisting Faith has a shortcoming, it is that more extensive treatment of certain topics would have been welcome, such as the chaplaincy’s interactions with atheism and homosexuality and the reasonings of military courts when they confronted contests between military demands and religious exercise. But this critique is hardly substantial; such deficiencies are relative to the considerable detail that Stahl provides on nearly all of the subject matter she addresses.

Overall, Enlisting Faith warrants high praise and a wide readership. Upon finishing the book, this reader was left hoping for a second volume that continues Stahl’s endeavor into the twenty-first century.