Inge Van Hulle’s article explores some of the main themes of her recent book, Britain and International Law in West Africa (Oxford University Press, 2021). Van Hulle seeks to uncover the international law practices and processes that made possible European hegemony West Africa, with a particular focus on treaties, use of force, and extraterritoriality.

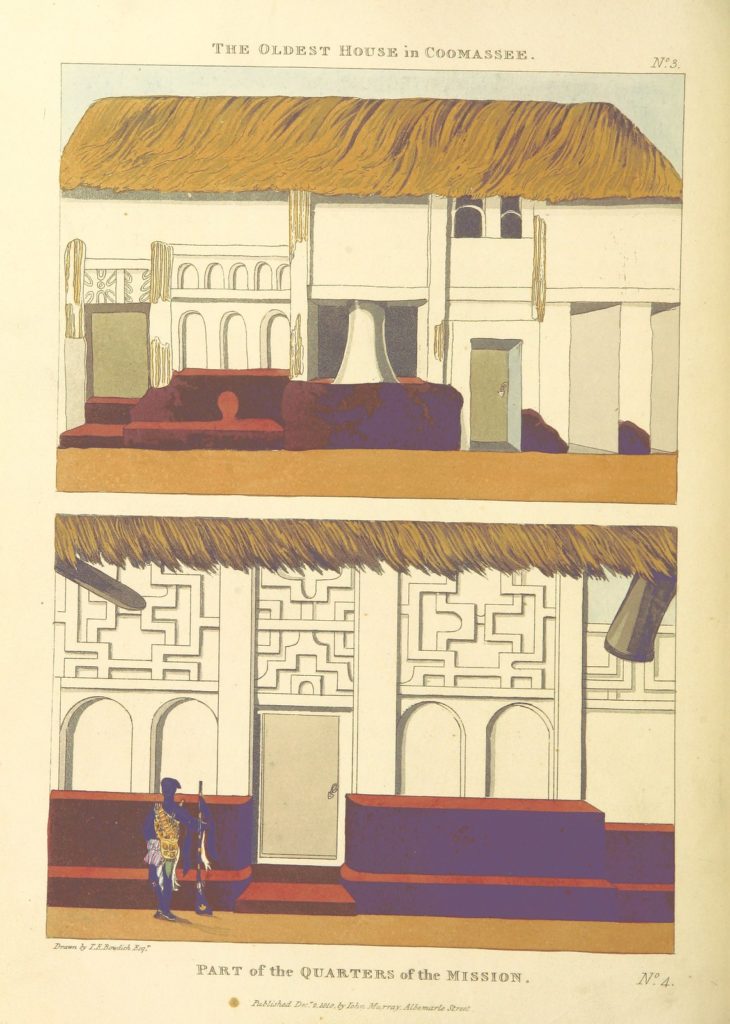

On 29 August 1817, Thomas Bowdich wrote to his superior, John Hope-Smith, that he had ‘the satisfaction to enclose a copy of the preliminaries to the general Treaty’ with the Osei Tutu, the king (aka the Asantehene) of Asante.[1] The letter forms part of Bowdich’ famous travel account, ‘A Mission to Ashantee’ in which he describes in detail the travails of a mission sent to Asante on behalf of the African Company of Merchants which administered the British forts on the Gold Coast (present-day Ghana). The idea was to establish peaceful trade with Asante in order to off-set Dutch competition and to smooth over some of the tensions that had arisen with Asante following its expansion in the direction of the coastline in the previous decade.

Bowdich was 25 years old at the time.[2] The son of a Bristol merchant, his superior penmanship and his family connections (John Hope-Smith was his uncle and Governor-in-Chief of the Company’s settlements) earned him a position as a clerk in the service. The expedition to Asante was headed by Frederick James, a company officer. Originally, Bowdich formed part of the mission as a scientific observer. However, after having become increasingly frustrated with the inept leadership skills of Frederick James and the protracted negotiations with the Asantehene, he set himself up as the new leader of the expedition and even had Frederick James recalled home. The treaty that Bowdich concluded with the Asantehene confirmed a mutual desire for trade and peace, but left open the thorny question of the overlordship over the Fante communities who lived in the vicinity of the British forts. In the treaty a reference to the Fante as ‘all nations residing under the protection of the Company’s forts and settlements was made’.[3] What did this protection mean? Was it some kind of watered-down version of Company sovereignty? Some kind of administrative responsibility, extraterritoriality or an alliance? In the end, the treaty created more confusion than it cleared up and by 1820 a new mission headed by Joseph Dupuis was sent to negotiate a new treaty. Nevertheless, the early mentioning of ‘protection’ in the Bowdich treaty paved the way for its increased use in the description of the legal relationship between the Company and Crown administrators of the forts on the Gold Coast and the neighbouring Fante over the years to come.

The failed Bowdich treaty is a good illustration of the way that international legal instruments were created in West Africa through the negotiation or imposition of British commercial, political, and ‘humanitarian’ demands vis-à-vis African communities at the start and middle of the nineteenth century. It shows that legal ordering was not done in reference to adjudication before courts or the writings of Western learned lawyers, but in reference to what was deemed politically expedient and practically feasible. International law in practice revolved around ‘vernacular’ international law.[4] Bowdich was a low-level company employee who was motivated not just by his official instructions, but also by his personal ambitions and by a chance to prove his worth in the face of his superior, Frederick James’ ineptitude. He did not form a part of the elite, trained lawyers of Europe’s law schools, nor was he very familiar with treaty-making or with pre-existing legal customs on the Gold Coast. Imperial law-makers, such as company officials, but also merchants, naval officers, colonial personnel or African rulers, operated under a range of theoretical assumptions that constituted their ‘legal imagination’ which was based on a particular consciousness concerning law, politics, trade, and what they considered as marks of so-called ‘civilized’ culture. Applying a new perspective that looks at the creation of international law on the ground and from a bottom-up point of view substantially revises a number of established truths about how international law and empire operated in Africa.[5] First of all, it means that we need to take seriously the period before the so-called Scramble for Africa when European states consolidated colonial control over Africa. Many of the instruments that would prove so important during the ‘Scramble’, such as for example, the protectorate, found their inspiration during the earlier decades of the nineteenth century. Second, it illustrates the chaos and haphazard nature of imperial international law-making.

“Thirdly, and perhaps most fundamentally, the gradual creation of European hegemony through international law in Africa was about more than just treaties that transferred land and sovereignty. It included legal techniques such as commercial or slave trade treaties, use of force, and extraterritoriality that have so far not been studied comprehensively with respect to West Africa.”

-Inge Van Hulle

Much of our information on international law and empire in Africa is still largely based on accounts of late nineteenth-century lawyers. In line with the positivist methodological ethos of the age, late nineteenth-century internationalists sought to find doctrinal consistency in vastly contradictory treaties and official state documents and, in their efforts, smoothed over the muddier aspects international law in practice. If we are to believe these accounts, then international legal techniques in Africa were ready-made constructs, to be categorized in relatively self-contained conceptual boxes, devised in European cabinets and applied in a top-down fashion to the African continent. Thirdly, and perhaps most fundamentally, the gradual creation of European hegemony through international law in Africa was about more than just treaties that transferred land and sovereignty. It included legal techniques such as commercial or slave trade treaties, use of force, and extraterritoriality that have so far not been studied comprehensively with respect to West Africa. These instruments were inherently entangled: humanitarian objectives to suppress the slave trade might lead to the conclusion of a treaty in which strategically located regions were ceded to Britain and which might, at a later point, be used to justify forcible intervention against African communities.

[1] Thomas E Bowdich, Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee (London: John Murray, 1819), 108.

[2] Sonia Abun-Nasr, “Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee. One Work’s Significance for European Knowledge Production about the Asante Empire” in Science, Africa and Europe. Processing Information and Creating Knowledge, ed. Martin Lengwiler, Nigel Penn and Patrick Harris (New York: Routledge, 2019) 105.

[3] Article 2, Treaty Made and Entered into by Thomas Edward Bowdich, Esquire, in the Name of the Governor and Council at Cape Coast Castle, on the Gold Coast of Africa, and on Behalf of the British Government, with Saï Tootoo Quamina, King of Ashantee and its Dependencies, and Boïtinnee Quama, King of Dwabin and its Dependencies, in Bowdich, Mission, 124.

[4] Inge Van Hulle, Britain and International Law in West Africa. The Practice of Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

[5] Inge Van Hulle, Britain and International Law in West Africa.