The defining event in the legal history of early modern Wales was the passing of the Acts of Union in 1536 and 1543. Wales in its entirety had been under English governance since the 1282/3 conquest of Wales by Edward I of England. The 1284 Statute of Rhuddlan formally annexed Wales to England, but the statute preserved Welsh custom and parts of Welsh law, creating dual legal systems for the native Welsh and the new English settlers respectively. It was a particularly important distinction for landholdings: land held under Welsh tenure was subject to cyfran, a form of gavelkind, and divided between the holder’s sons at his death; land held under English tenure followed the principles of primogeniture and thus the eldest son inherited it. Welsh land fragmented into smaller holdings with every generation, but English land tenure permitted the development of estates.[1] This dual legal system caused complications because it was possible for one person to have multiple landholdings, some held under English tenure and others under Welsh tenure. The Acts of Union addressed these complications by abolishing the Welsh legal system, including Welsh land tenure, and extended English liberties, rights, and law to Wales. After 1536, everyone in Wales was English under the law.[2]

The Acts of Union devolved the administration of Wales to the Welsh gentry, the families who provided leadership in their local communities. Traditionally, the Acts of Union are seen as a watershed in Welsh history; according to this view, the extension of English rights and liberties, as well as the requirement for officials to speak English, caused the Anglicization of the Welsh gentry and established them as a social order who increasingly isolated themselves from their communities. My doctoral research looks at the legal records of one Welsh gentry family, the Salesburys of Rhug and Bachymbyd. These include both the family’s own papers, mainly deeds, and the records of local and national courts. The legal records show that the Salesburys embraced a Welsh identity both before and after the Acts of Union, challenging the notion of Anglicization. The Salesburys became Welsh before the Acts of Union and they stayed Welsh after the Acts of Union.

The Salesburys of Rhug and Bachymbyd were the descendants of English settlers, the Salusburys of Lleweni, who arrived in Denbighshire, north Wales, after the Edwardian Conquest. By 1536, however, the Salesburys of Rhug and Bachymbyd were a notable Welsh gentry family in their own right; they had married into Welsh families and obtained two estates, both originally held under Welsh tenure and thus subject to Welsh land law. John Salesbury (b. circa 1450) was a younger son and thus he had little hope of inheriting his father’s English estate at Lleweni. Instead, John purchased his own estate at Bachymbyd in Denbighshire. This land, however, was held under Welsh tenure and thus it was illegal to sell or alienate it; the land belonged to the kindred alone. Instead, John utilised a form of mortgage which had gradually developed in late medieval Wales to circumvent the restrictions on the sale of Welsh land.[3] In 1482, John leased the house and demesne of Bachymbyd from its existing owner, Madog ab Ieuan, for twenty pounds and a term of four years, which continuously renewed until Madog repaid the twenty pounds. In reality, Madog would never repay and, indeed, never intended to repay the mortgage; John bought Madog’s estate at Bachymbyd for twenty pounds. Although the Salesburys were originally English settlers in Wales, John was willing and able to utilise the Welsh land market to purchase his own estate. The Salesburys’ English origins did not prevent them from engaging with the Welsh land market. John later converted Bachymbyd to English tenure through letters patent from King Henry VII, thus the whole estate descended to his eldest son.

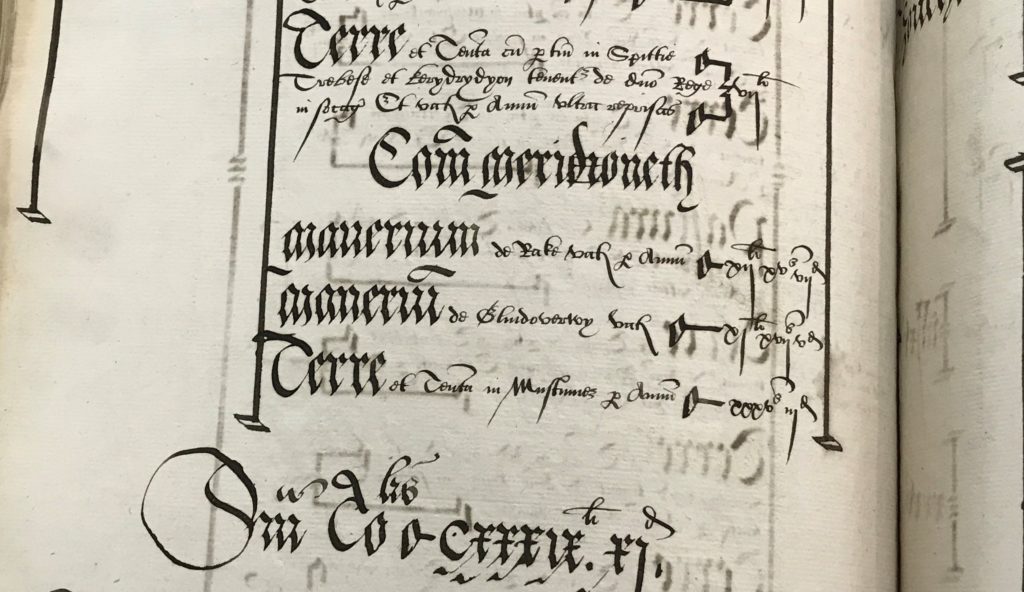

The Salesburys acquired the Rhug estate in neighbouring Merionethshire through the marriage of John Salesbury’s son, Piers, and Margaret Wen, the Welsh heiress of Rhug. This marriage became a key part of the Salesburys’ identity as a Welsh gentry family. Through Margaret Wen, the Salesburys became barons of Edeirnion, successors to medieval Welsh lords who had survived the Edwardian conquest and held their land directly from the Crown or Prince of Wales by ‘Welsh barony’. Piers and Margaret’s son, Robert (d.1550), was described as ‘baron of [E]dernion’ in a deed of 1548.[4] This title came with privileges, such as the right to hold a court, but it also gave the Salesburys a distinguished, Welsh ancestry. The Salesburys’ use of this title in their deeds demonstrates that they valued it and that it contributed to their status and sense of identity. Before the Acts of Union, the Salesburys recognised advantages in being Welsh; it gave them lineage, status, and a claim to leadership.

In contrast to the dominant narrative of Anglicization, the Salesburys also remained Welsh after the Acts of Union. For example, legal records demonstrate that the family continued to be Welsh speakers, which was vital for communicating with their servants and tenants. In a 1574 Star Chamber suit, John Salesbury (d.1580), the patriarch of the family, was accused of murdering a Denbighshire justice of the peace. Most of John’s co-defendants in the suit were part of his retinue and they had sworn an oath to protect his property in a dispute with another gentleman. A Welsh gentleman’s retinue, or plaid, was a culturally significant feature of late medieval and early modern Wales.[5] When the justice of the peace arrived to disperse John’s men, he read a proclamation to ask the men to disperse. The men said in their defence that they could not understand the proclamation because it was in English and they only understood Welsh. This might be simply a convenient defence, but an English jury from Shropshire also complained that they could not understand the deponents in the suit and needed to rely on translators. John Salesbury, the leader of the men, was able to communicate with his retinue and thus he could certainly speak Welsh. John, like the murdered man, was a justice of the peace, and so he could also speak English, a requirement of the role. John Salesbury was not Anglicized after the Acts of Union; he continued to speak Welsh and engage in Welsh cultural practices.

In the 1670s, William Salesbury of Rhug sued his cousin, Dame Jane Bagot, for the ownership of the Bachymbyd estate. William’s grandfather had bequeathed Bachymbyd to his younger son, Charles, rather than his elder son, William’s father, Owen. Instead, Owen received the Rhug estate which passed after his death in 1658 to William. The Bachymbyd estate, meanwhile, passed to Charles’ only child, Jane, who inherited it in 1666. Jane married Sir Walter Bagot of Blithfield Hall, Staffordshire, the heir to a prominent English gentry family. For full details of the dispute, see my recent article on ‘Credibility in the Court of Chancery: Salesbury v Bagot, 1671-1677’, published in The Seventeenth Century.[6] When William first threatened to sue the Bagots for Bachymbyd, the Bagots expressed concern over a potential trial in Denbighshire; they received legal advice advising them to be wary of ‘the jealousy of a Welsh Jury where an English man is concerned’.[7] The implication, of course, is that a local jury would favour the Welsh Salesburys over the English Bagots. A century and a half after the Acts of Union, the Salesburys still remained a recognisably Welsh family and there were demonstrable advantages to this identity when they engaged with the local legal system.

The legal records of the Salesburys

of Rhug and Bachymbyd demonstrate their sense of self as a Welsh gentry family.

These records establish that the Salesburys willingly embraced Welsh law prior

to the Acts of Union, despite their origins as an English family. They also show

that the Salesburys were not Anglicized and isolated from their communities

after the Acts of Union; the family remained connected to the people of their

local society through language and culture, and local society continued to

recognise the Salesburys as a Welsh family. Legal records are thus an unusual,

but invaluable source for understanding the early modern Welsh gentry and how

they perceived themselves.

[1] For the details of Welsh inheritance practices, see Thomas Charles-Edwards, Early Irish and Welsh Kinship (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), chapter 4.

[2] Glanmor Williams, Renewal and Reformation: Wales c.1415-1642 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), chapter eleven.

[3] Llinos Beverley Smith, “The Gage and the Land Market in Late Medieval Wales”, Economic History Review, New Series, 29, no. 4 (1976): 537-550.

[4] Caernarfon Record Office, XD2/1149.

[5] A.D. Carr, The Gentry of North Wales in the Later Middle Ages (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2017): 20-21.

[6] Sadie Jarrett, “Credibility in the Court of Chancery: Salesbury v Bagot, 1671-1677”, The Seventeenth Century (2019 online), DOI: 10.1080/0268117X.2019.1694060.

[7] National Library of Wales, Bachymbyd Letters 115.