Introduction[1]

This essay examines the representation of seventeenth-century colonial North America in early Native American literature. While the history of Native-colonial relations of this period is complex, conflict was an inevitable and often dominating part of those encounters, and, in turn, drew the attention of Native writers and historians: Samson Occom, Elias Boudinot, Black Hawk, and William Apess, whose works we examine. While we attempt to focus on the perception of conflicts, the larger issue addressed here is the perception of history in general, of how history was seen drastically different by different cultures of North America, how history was re-told and written by Native American authors with their unique position on the intersection of cultural traditions. The next logical question, which we briefly touch upon (and hope to explore further in the future) is how all those differing ideas of history influenced the lives, philosophies, and politics of both individuals -Native writers and activists – and whole communities.

But first, it might be prudent to give a very brief overview of the events of seventeenth- century as we see them today, to provide context for understanding the texts we examine. A necessary disclaimer concerning the geographic boundaries of our study — when talking about seventeenth- century North American colonies is that we mean mostly the New England colonies. While both Virginia and the Carolinas were indeed founded in the seventeenth- century, in later historic writing on the period they occupy a far less important position than the New England colonies. Simply put, when talking about the founding of America, early historians, both Native and Euro-American, mostly mean the founding of New England. We realize, of course, that from our modern point of view, this is a reductive, limited, and generally unproductive approach, but since our primary concern is historical thinking, not history as such, we will follow our primary sources in this regard.

The founding of North American colonies became an integral part of the foundational myth of the United States — the Pilgrim Fathers landing on Plymouth Rock, the founding of Boston ten years later, the whole complex of mythological, legendary, and occasionally even historic images surrounding Thanksgiving, should all be familiar to anyone with even a vague notion of American history. Of course, the reality was far more complex than such popular images suggest or even hint at, but we are primarily concerned with the general idea of history at this point. The early colonial conflicts, Native-colonial conflicts in particular, occupy a far less prominent place in public image of American history.

The first such conflict in New England was the Pequot war in mid-1630s. The Pequot people were a Native group exerting a significant influence over the Connecticut River valley area, the territory that both the colonists and a number of other Native groups were interested in. Rapid expansion of the Massachusetts Bay Colony caused tensions to escalate and eventually a conflict erupted, with Pequots on one side and the English and their allies (numerous, probably outnumbering the colonists) on the other. The war left the Pequots decimated, and the survivors were distributed among the English and their allies, though some eventually returned to their ancestral lands. During the war, the English demonstrated their conceptof waging war against Native peoples by massacring Pequot non-combatants during the destruction of a Pequot settlement on Mystic River, to the horror of both Pequots and English allies. While the Pequot War was (and to a degree still is) mostly overlooked by historians, it is important for our topic, not just because it was the first open Native-colonial conflict, but also because William Apess, one of the authors whose work we examine, was a Pequot.

The second major conflict of the period was King Philip’s War. The New England colonists and their (by now less numerous) allies clashed with the Wampanoag — Philip/King Philip was the English name for Metacom, the Wampanoag chief sachem(chief; though Native American leaders are sometimes referred to as chiefs, most historians today prefer the Native term sachem, to distinguish a specific type of Native American leadership from similar power structures in other societies). The colonists were victorious, again, but the war certainly took its toll on the colonies, and the victory was not an easy one -— in fact, at first it seemed that the Wampanoag were winning. It was primarily the intervention of the New York Mohawks, who saw the opportunity to deal a serious blow against their old enemies the Algonquians of New England, that ensured the English victory. The outcome of King Philip’s War was English political domination of the region.

King Philip’s War subsequently became the origin point for one of the most persistent myths about Native Americans in New England and later in other parts of the continent, that of the “vanishing Indian.”The core idea of the vanishing Indian myth is simple – the Indians are, indeed, vanishing, disappearing, they ultimately have no chance of holding their ground against the technologically superior Europeans, and their culture will not survive contact with “civilized” European ones, so even if the Indians survive physically they will assimilate completely and without a trace, their culture and way of life will drift off into obscurity, products of a bygone pre-historic age. This foundational idea was supplemented by an understanding, implicit in many early narratives and scholarly works, that the Indians themselves recognized they were vanishing and were thus,resigned to their inevitable destiny. In reality, most Native groups survived, though diminished, as people who managed to preserve their culture and traditions.

The struggle for cultural survival thankfully, has increasingly became an object of active research in recent decades. However, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the period our sources were created in, the vanishing Indian image was still firmly believed in, forming the basis of Euro-American understanding of Native-colonial relations, and inevitably deeply affecting the mindsets of the Native historians we will examine: Samson Occom, Elias Boudinot, Black Hawk, and William Apess.

The above mentioned Indian wars, while not as prominent in public consciousness as the Revolutionary War or the Civil War, still have a place in the popular image of American history – a place constructed by the early colonial authors according to their perception of the nature of these conflicts. And the ideological legacy of the colonial writing of history, such as the “vanishing Indian” myth, still in many ways defines the popular understanding of the earliest period of European expansion in the New World.

Samson Occom

Native American literature was, of course, a product of an amalgamation of cultural traditions — the very act of learning to read and write, not to mention publishing, was generally only accessible with mediation from the English. Despite that, the Native authors we will focus on definitely saw themselves as Indians first and foremost and stressed that aspect of their identity.

The first Native American whose writing was published in North America was Samson Occom (1723-1792), a Mohegan Presbyterian preacher and what we would call today an activist. Occom, who converted to Christianity around 1743 (influenced by the charismatic evangelical preachers of the Great Awakening) is well-known for his missionary work, his involvement with establishing the Brothertown Indians community, and his attempt to establish a college for providing Native Americans with education (the college, for which Occom acquired the funding, Dartmouth College, was eventually established, but due to the machinations of Eleazar Wheelock, did not admit Native Americans). Today, Occom’s writings are not widely known and were less known during his lifetime mostly because very little of this creative output was published — A Sermon Preached at the Execution of Moses Paul, an Indian… (1772), and A Choice Collection of Hymns and Spiritual Songs (1774) are exceptions.

And in most of his published works, Occom says remarkably little of Indians in general, Indian history in particular, and of himself as an Indian.The opening passage of “A Sermon Preached at the Execution…”expresses worry that the sermon might not be taken seriously coming from an Indian. Occom was, of course, keenly aware of the widespread prejudice of the time and a critique of this prejudice can be seen in the sermon’s opening, but another reading is also possible. Occom goes on to state that his language is simple and mundane, since he himself is a simple and uneducated person, so that”even my poor Indian brethren” can understand him. This humble near-apology at the start of the work is actually quite common in the European literary tradition, and similar passages are found in many theological works from early middle ages onward. Reference to Indian origins differ from the standard formula, but ultimately serve the same purpose, and to demonstrate to the reader (and, presumably, the audience at the sermon) Occom’s familiarity with theological literature. The social and cultural critique, if present at all, is quite tame—no more than a secondary sub-text in an updated version of a traditional literary formula. Reflection on history seems to be completely absent. This absence of “visibly Native” elements and evaluations of English-Native interactions in Occom’s published works may be easily explained. In my opinion, it should be considered a result of Occom’s desire to avoid confrontation with a predominantly white audience that would thus endanger his missionary and civic work among the Indians.

Occom’s unpublished works, his journals and letters, show clearly that he was very much aware of the prejudice that Native Americans faced. He was sharply critical of colonial culture and it is hard to imagine that he somehow completely avoided reflecting on history of Native-colonial relations. But all this critique remained concealed from the reading public (we have no way of determining if Occom expressed his disdain in unrecorded public speeches), for practical reasons. It seems, Occom was a preacher first and an activist second, as would not jeopardize his work through publishing anything that might spark conflict with the dominant culture.

Elias Boudinot

Unlike Occom, Elias Boudinot (1802-1839), a Cherokee journalist, writer and activist, wrote primarily of Indians and of himself as an Indian, examining thoroughly both the current position of the Cherokee community and, crucially for us, Indian and Indian-colonial history. He was a well-read, highly educated, financially secure man of mixed ancestry, who chose to direct all his energy to helping his people, the Cherokee. He is also often characterized as being “stuck” between cultures, of being”ambivalent in his loyalties,” “problematic,” or of being outright “traitorous.” His impact on the position of Native Americans in the US was, indeed, controversial at the very least. Boudinot, despite the opposition from the Cherokee leaders and the majority of the people, signed the Treaty of New Echota, which laid the groundwork for the Trail of Tears. Despite all of his contributions — being the editor of The Cherokee Phoenix, translating the Bible into Cherokee — and despite his criticism of many US policies towards Native Americans, Boudinot was branded a traitor and assassinated by fellow Cherokees.

Boudinot’s personal politics were very much grounded in his view of history and the Native American’s place in it. His understanding of history shares a few key assumptions with contemporary Euro-American historiographers. Firstly, Boudinot wholeheartedly believed in the cruelty of “savage” Indians. This cruelty stemmed not from some natural inclination but rather, that it was characteristic of any “uncivilized” population. And that such “savagery” would slowly cease after the contact with the “civilized” English, and later with the United States. For Boudinot, the Colonial period was a crucial and necessary stage of improvement that spurred them the Indians towards the heights of civilization. He criticized, sometimes sharply, the US government for underestimating the Indians or for hindering their advancement for immediate profit, thus jeopardizing the grand civilizing mission, but not for the prejudice against “savages” as such. He was also critical of Native customs/beliefs and he believed that the only way to achieve civilized status — and to eventually eliminate prejudice against Indians — was by abandoning the traditional way of life through the embracing of European culture and innovation. This, however, doesn’t mean that Indians had to stop being Indians. Boudinot did not promote, consciously or unconsciously, the “vanishing Indian” myth. On the contrary, he insisted on the capacity of Native culture to evolve, adapt and adopt “civilized” cultural practices, while retaining the core Indian identity — for all his admiration of European material civilization and Euroamerican culture, Boudinot was very clear about the distinctiveness of Native people.

Boudinot’s fascinations with progress and his somewhat naïve, from modern perspective, faith in it, is very much in line with nineteenth century Western ideas of progress in history. Boudinot’s concept is very similar to the later ideas of a precursor of modern political anthropology, Lewis Henry Morgan. Morgan believed in the existence of a universal path of development (i.e. the same pathway for all human societies). This notion implied that all human societies were capable of eventually reaching the heights of civilization while any setbacks on this progression were attributable to external circumstances. Morgan did not invoke racist explanations to explain why different humans societies experienced differential levels of civilization. According to Boudinot, this is exactly what was happening to Indians. They were passing from the stage of barbarism to a civilized state. Morgan explored the mechanisms of social evolution in detail, while Boudinot focused on inserting Native Americans, considered to be “vanishing Indians” at the time,back into the general flow of human progress. For all his insistence on his own Native identity and Native perseverance in general, Boudinot’s understanding of history along with the impact of Native-colonial relations was very much in line with a European understanding of history. We will return to Boudinot when we search for traces of “traditional” history in his writings.

Black Hawk

Black Hawk (1767-1838) may seem at first glance to be somewhat out of place in the list of Native American writers we examine. For starters, he was not exactly a writer. Black Hawk was a Sauk sachem who lead his people in wars against the United States, first siding with the British in the War of 1812, and later in the eponymous Black Hawk War. His autobiography was recorded (and inevitably edited) while he was imprisoned after the latter conflict. Its authenticity was questioned on multiple occasions, with accusations ranging from the English “editor” influencing the general direction of the narrative all the way to the entire work being judged a complete fabrication. Today, it is generally accepted that the text was indeed a record of narration by Black Hawk himself, and while some misrepresentations are inevitable, the majority of the text is considered to be authentic. While Black Hawk may not fit the exact definition of a Native American historian, he most certainly should be considered as being a Native American author.

Secondly, Black Hawk’s narrative does not even mention any early Native-colonial conflicts, focusing instead, on Black Hawk’s own life and the lives of his immediate ancestors. And his narrative is certainly not concerned with the New England colonies — Black Hawk’s tale takes place a century later and hundreds of miles away. But Black Hawk’s narrative provides us with an image of history so drastically different from other Native writers that it would be wise to give it careful consideration. His narrative also provides a perfect counterpoint to the historical thinking of William Apess, whose works are of major interest to historians. Black Hawk’s history is Native history, or as close as we can get to it without leaving the realm of literature altogether.

In terms of historical thought, what first draws attention in Black Hawk’s autobiography is the lack of dates. In the entire text, there are just a couple of dates, and even these seem chronologically disjointed, almost like the aforementioned misrepresentations. In this narrative, time, historical time specifically, is not tied to an absolute chronology. Instead of dates, Black Hawk’s chronology is focused around specific events – new sachems assuming power, the transferring of the medicine bag, etc. The second specific feature of history in Black Hawk’s autobiography is its focus. There is no mention of ’Indians’ as a general category here. Unlike Boudinot, who, while focusing on the Cherokees, viewed Natives as a whole as being on the path towards civilization, Black Hawk’s narrative is the history of the Sauk. Other Native groups are only occasionally mentioned as either allies or enemies.But the general opposition of Indian and white, Native and colonial, prominent in European historiography of the period, in Boudinot’s and Apess’s writings, is not found in Black Hawk’s autobiography. There is no grand, all-encompassing narrative. On one occasion, Black Hawk ruminated on Indian-White relations in general, but only very briefly, and likely prompted to do so by an editor.

An obvious difference from Western historical writing and the historical thought of the era is thecomplete absence of references not just to written sources, but to any sources of information external to the community. The only authority cited was the oral tradition and, in Black Hawk’s case, what he witnessed. This is in direct opposition to both Boudinot’s and Apess’ approaches. This absence of a need for outside confirmation makes history legendary, even mythological in nature. The events beyond the life of the current generation, including the early colonial period, have a recognizable mythological flair, especially in the story of first contact with Europeans. This event was foretold to Black Hawk’s ancestor in a prophetic dream, and he observed a number of specific taboos for several years awaiting the prophesized event. The practice of describing events via a legendary-mythological lens imbued such events with a significance that was often lacking in Euro-American narratives. However, this practice may also diminish the importance of the narrative as the text may simply be dismissed as just being another ‘myth.’Myths, while serving as moral points of reference, may be considered of little practical use when confronting the destructive forces of colonization.

The last point that should be mentioned about Black Hawk’s history is it mournful nature. At first glance,it might seem that it is a story about a people in decline, soon to be gone completely – quite in line with the “vanishing Indian” myth. In reality, this is an element of the folklore tradition. Bemoaning the passing of an old way of life is not about Native peoples dying and disappearing but rather, it is about change and renewal. In essence, the old way of living will no longer be feasible and this is worth lamenting. However, Natives were not to vanish from the earth completely. Indian ways of life will continue but in a new and in sometimes unfamiliar forms. Therefore, Black Hawk’s lamentation should not be viewed as an expression of a fatalistic resignation to the disappearance of the American Indian (a belief that many Euro-Americans of his time embraced). Instead, Black Hawk held that the changes that Native peoples are undergoing would in the end, result in the renewal of American Indian societies.

William Apess

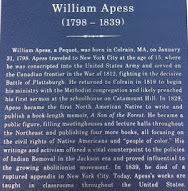

Black Hawk’s understanding of history is in stark contrast to the views of William Apess (1798-1839). Apess, a preacher, writer and activist of Pequot ancestry, was active in New England in 1830s, and was widely known both for his public preaching, his writing and for his participation in a series of peaceful protests later dubbed The Mashpee Revolt in 1833-34. Out of Apess’ writings, of paramount interest is his autobiography, A Son of the Forest (1829), and The Eulogy of King Philip (1836, a published version of a lecture Apess gave several times in 1836-37). Unlike Occom, Apess wrote extensively about Native American experiences, Native American history, and Native American identity. Unlike Boudinot, he was sharply critical of European colonization. Being a devout Christian, he acknowledged the role that Europeans played in spreading the Gospel among Indians, but Apess did not share Boudinot’s fascination with notions of progress. In fact, Apess did not hesitate to condemn the cruelty of Europeans. Moreover, he denounced the hypocrisy of Europeans who claimed to promote Christian values while treating Indians in a decidedly non-Christian manner. Appes also paid much attention to the history of Native-colonial relations, especially to King Philip’s War.

The first thing that is immediately noticeable in A Son of the Forest is the fact that Apess, a Pequot, insisted that Philip was a Pequot “king” and that it was the Pequots who fought against the English in King Philip’s War. That is factually incorrect. Metacom\Philip was, in fact, a Wampanoag sachem. Also, by the time that the King Philip’s War had taken place, the Pequots had lost their political independence. If any Pequots had actually fought in this war, they had most likely fought on the side of the colonists. All this was well known — it was this mistake for which Samuel Drake, an antiquarian and a supposed major authority on Native American history at the time, criticized Apess, advising him to “learn the history of what he is writing about.” The crucial point for us, though, is not the “mistake” itself, on which Apess insisted stubbornly, but the fact that its source was not Native oral tradition (something he learned from other Indians), but rather it came from a mistake found in an early scholarly work. Unlike Black Hawk, Apess consulted an impressive amount of external sources. His Eulogy… and A Son of the Forest are full of references and quotations (some going on for several pages). Apess’ assessment of the history of Indian wars is different from that of European historians, but it is nevertheless history as Europeans understood it at the time — documentary, chronological, striving (or at least claiming to) to avoid “legendary” elements. Like Boudinot, Apess attempted to place Native Americans within the general framework of global history. But instead of using the idea of a universal path towards civilization, he equated Native and European histories. An example of this can be found in how he compared Philip to notable historical figures such as Alexander the Great and George Washington.

Despite his emphasis on his own Pequot identity, Apess framed Native American history very much as a history of Native-colonial opposition, with little regard to inter-tribal differences or inter-tribal conflicts. In his interpretation of King Philip’s War, Philip and the Pequots (standing in for the Wampanoag) serve as a quintessential example of this historic Indian-European opposition. While on individual level, Apes recognized the importance of his own Pequot identity, when considering the Indian-European relations in general he seemingly saw no point in separating Indians into distinct groups in their opposition to Europeans. This approach seems alien to contemporaneous Native views such as those expressed in Black Hawk’s Sauk-specific history. However, Apess’ approach resonated with later pan-Indian concepts and perceptions.

In his Eulogy…Apess created a vivid image of Metacom\Philip. For early colonial authors, Philip was a monster, a cruel, brutal, and treacherous savage, barely distinguishable from a wild animal. For Apess, Philip was a wise, noble, and generous leader. He also believed Philp to be a political and military genius.In fact,at the dramatic high point of Eulogy…,Apess claimed that Philip was the greatest leader to have ever lived in America and compared him favorably to George Washington. This in and of itself is to be expected because a positive portrayal of Philip is a logical conclusion of Apess’ entire approach to Native-colonial relations. Less obvious is the fact that such an image is quite in line with later Euro-American interpretations. Late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century Anglo-American historians often described Philip with respect and even compassion, noting the difficulty of his position while criticizing the cruelty of the colonists. Apess goes further than that, but not by much. But he also attempted to show that Indian history even in New England did not end with Philip’s defeat — the condescending generosity of subsequent Euro-American authors stemmed from perception of Natives as long gone, and of Philip as a romantic figure of a bygone age: somewhat nostalgic, but ultimately irrelevant. Apess stressed the perseverance of Native American culture — his commitment to both his own and Philip’s Pequot identity showed the reader quite clearly that Philip’s people were still here, still active, and still very much Native American. He framed Philip as an active part of contemporary historical discourse by comparing him to other notable figures of American and European history. His idea of early Native-colonial history as highly relevant was certainly unique. But the positive portrayal of Philip was not. Some of Apess arguments, such as considering Philip’s attack against the colonies as the only possible course of action in his situation, were clearly influenced by contemporaneous historiographers. Apess’ view of Philip is a perfect example of his historical craft — clearly intended to serve the interests of the Native Americans, clearly in active opposition to the “vanishing Indian” myth that was prominent in Euro-American thinking, but also clearly based on a Euro-American understanding of history, albeit striving to portray Native American history as part of a global history of human development, thus equating it with European history, and firmly tied to the historiographic tradition.

Some scholars consider the entire Eulogy… and Apess’ work in general, to fit with the mournful Native folklore tradition. While such a reading is possible, it is important to remember that Apess was clearly opposed to the widespread “vanishing Indian” mythology. Indeed, there is an element of lamentation regarding the passing of the old, somewhat idealized, way of life in his writing. However, it is important to note that Apess and Boudinot, while lamenting the passing of the old way of life, both celebrated the capacity of Native Americans to persevere and to adapt.Both adopted the language of Euro-American history-writing, but they replaced the “vanishing Indian”myth,characteristically embraced by colonial era historians, with the belief in the future renewal of Native culture along with a powerful insistence on the survival of Native societies in the face of adversity.Both, therefore, subverted the widespread “vanishing Indian myth completely. The notion, which resonated with their Native backgrounds, became, in their writing of history, an instrument of asserting the identity, agency, and persistence of Native American societies in the face of the “vanishing Indian” myth.

Conclusion

While the very first published Native American writer, Samson Occom, generally tried to avoid antagonizing his predominantly white audience in his works available to the public, XVIII-XIX centuries Native American literature, namely the writings of Elias Boudinot and William Apess, contained numerous reflections on history, examining both the specific events and early colonial conflicts (Apess) and the general course of global history (Boudinot). The way Boudinot and Apess viewed history was in many aspects similar to Euro-American historical thinking. This was drastically different from traditional Native perception of history, vividly demonstrated by Black Hawk’s narrative. One crucial difference between Native and European writers was their opposition to the “vanishing Indian” myth in its various forms. While acknowledging the inevitability of change, Boudinot and Apess insisted on the Native American’s ability to adapt and persevere in the face of changes brought by colonization. They successfully adjusted to European concepts of history, ways of thinking, and writing history, to serve the needs of Natives. Their writings were and continue to be an important tool for preservation of Native identity.

[1] This is a product of an ongoing project in relatively early stages, and the conclusions presented here are very much preliminary. I would also like to take this opportunity to, once again, express my gratitude to Dr. Richard J. Chacon from Winthrop University for his help in editing these remarks. The research presented here has received funding from the Basic Research Program at the National Research University Higher School of Economics(Moscow, Russian Federation).