Public Trust and Public Access: Deborah Dinner Reviews Free the Beaches

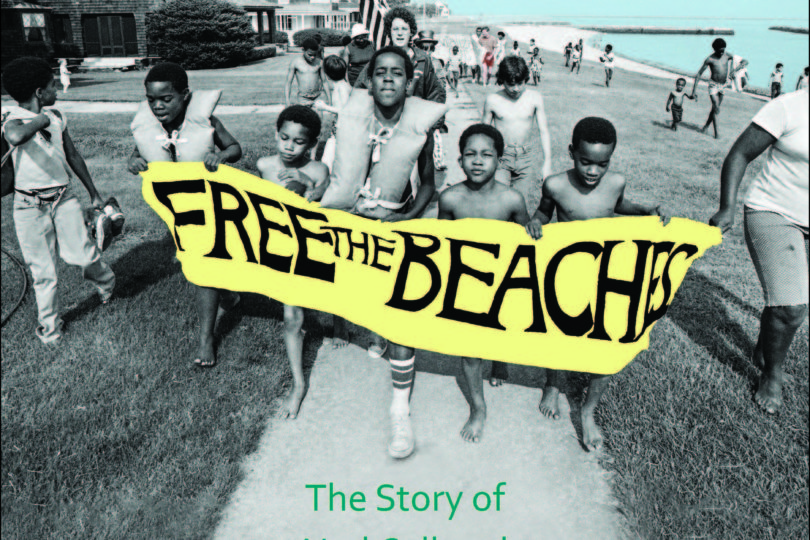

On July 4, 1974, a daring, no-holds-barred activist named Ned Coll launched an amphibian assault on an exclusive Beach Club in Madison, Connecticut. Coll’s comrades included more than fifty children from nearby Hartford’s poor, majority African-American housing projects. The children, their mothers, and staff members of Revitalization Corps, an advocacy organization dedicated to racial equality and justice for the poor, were clothed in bathing suits and armed only with laughter, songs, and excitement. Yet the affluent white parents on the beach saw the newcomers’ entry as an ambush and quickly retreated, children in tow, to their private club. The episode constituted one highlight of Coll’s campaign to win public access to the beaches along the shoreline of a state plagued by extreme wealth inequality.

A somewhat obscure common law doctrine—newly and hotly contested in the 1970s—rested at the heart of Coll’s creative protest of the Madison Beach Club. The public trust doctrine, recognized in the United States Supreme Court case Illinois Central Railroad v. Illinois, (1892), specified that navigable waters belonged to the public and that the state could not sell or delegate control over these waters to a private entity. This holding, however, left open multiple legal questions. Should the public trust doctrine apply to swimming and sunbathing as well as fishing and water travel? Did it extend to the dry sand and not only the wet sand? Could affluent white towns restrict the scope of the “public” to their own residents? Could they do it indirectly by banning or limiting parking?

Free the Beaches joins an important body of scholarship plumbing the depths of racism in the North. Historian Andrew Kahrl argues that New England manufactured its own brand of Jim Crow that operated “through ostensibly color-blind and race-neutral land-use regulations and the privatization . . . of public space” (13). The book begins by recalling how, in the first half of the twentieth century, the federal government, localities, and real estate boards all produced a racial divide between cities and suburbs. Kahrl’s focus on the Connecticut shoreline newly illuminates the ways in which wealthy white suburbanites strove to preserve their towns’ inflated property values and social exclusivity, from mid-century through the present. They fought hard to keep poor people of color out of ostensibly public schools, allegedly free housing markets, and state parks and beaches. When judicial and legislative action made explicitly discriminatory practices unlawful, advocates deployed formally race neutral traditions of private property and local autonomy. Kahrl notes that Connecticut’s affluent white enclaves used what political scientist Margaret Weir terms “defensive localism” to keep outsiders at bay (p. 35).

Legal historians will be particularly interested in what this history has to say about federalism. Like Karen Tani’s recent book States of Dependency: Welfare, Rights, and American Governance, 1935-1972 (2016), Kahrl’s work depicts federalism not as a duet but as a trio featuring localities as well as states and the national government. One mechanism of such localism was the appeal to what historian Camille Walsh calls “taxpayer citizenship” (Racial Taxation: Schools, Segregation, and Taxpayer Citizenship, 1869–1973 (2018)). Opponents of inclusion, Kahrl explains, argued that their local taxes gave them exclusive ownership over their towns’ beaches. Attorneys seeking inclusion for Connecticut’s broader public were able to crack fissures in defensive localism by exposing localities’ interdependence with other levels of government.

In analyzing the battles over Connecticut’s beaches, Kahrl deftly illuminates shifts in liberalism from the sixties to the seventies. His protagonist, Ned Coll, fought to preserve John F. Kennedy’s vision for a “New Frontier” and embraced Robert Kennedy’s position that liberal ideals came with a cost—one that the privileged should pay (p. 120). Coll’s political philosophy butted up against a “growth liberalism,” championed by Lyndon Johnson, which did not demand self-sacrifice (p. 121). When the pie stopped expanding in the early 1970s, the New Right was able to caricature federal anti-poverty programs as serving the interests of a leviathan bureaucracy committed to crude redistribution. In this broader political context, Coll’s activism hit a wall. While Kahrl celebrates activists’ hope and determination, Free the Beaches ends on tragic notes.

Free the Beaches is essential reading for historians interested in income and racial inequality, land use, and the relationship between law and social movements. Writing with passion and eloquence, Kahrl deftly fuses social, legal and environmental history, arguing that towns’ exclusionary practices ultimately heightened the vulnerability of the Connecticut shoreline to climate change. While Kahrl’s centering of one man’s story yields a powerful narrative, this focus sometimes sidelines the legal history in the book. Kahrl’s analysis piqued my curiosity about the public trust doctrine more than it satisfied my questions about the doctrine’s legal evolution. Nonetheless, legal historians—and particularly those who teach Property to law students—might never approach the beach, their classrooms, or the drive along I-95 towards Greenwich and Manhattan in quite the same way, after reading this fascinating book.

Deborah Dinner is Associate Professor at Emory University School of Law. She is currently preparing a book manuscript titled The Sex Equality Dilemma: Work, Family, and Legal Change in Neoliberal America. She tweets at @deborahdinner.