Felice Batlan is Professor of Law, Director of the Institute for Compliance, and Co-Director of the Institute for Law and the Humanities at the Chicago-Kent College of Law. She was previously an Associate Editor of Law and History Review. She is the author of several major works, including Women and Justice for the Poor: A History of Legal Aid, 1863-1945 (Cambridge University Press, 2015). She is a graduate of Harvard Law School, earned her Ph.D. in History at New York University, and clerked for the Honorable Constance Baker Motley of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. She can be reached at fbatlan (at) kentlaw.edu.

She is the author of several major works, including Women and Justice for the Poor: A History of Legal Aid, 1863-1945 (Cambridge University Press, 2015). She is a graduate of Harvard Law School, earned her Ph.D. in History at New York University, and clerked for the Honorable Constance Baker Motley of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. She can be reached at fbatlan (at) kentlaw.edu.

On Friday January 27th, 2017, Donald Trump executed the infamous Executive Order —-banning immigration and even travelers from seven countries. The order affected those with travelers’ visas headed to the United States as well as U.S. permanent residents from seven banned countries attempting to re-enter the United States. By Saturday morning, tens of thousands of protestors appeared at airports denouncing what quickly came to be called the “Muslim Ban.” Protestors chanted to the world, “Immigrants are Welcome Here.” At times, neither those affected by the ban nor the protestors were the stars of these dramatic events. Rather, attorneys who had also gathered spontaneously became central to the story and the ongoing crisis.[1] As organizations such as the ACLU and other immigrant rights groups began to mount lawsuits to challenge the ban, volunteer attorneys staffed makeshift airport desks.[2]

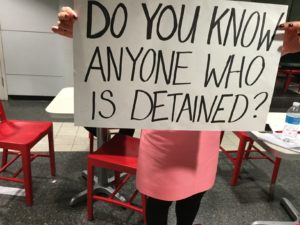

At Chicago’s O’Hare airport, lawyers walked through the crowd at the international arrivals area with handmade oak tag placards that read “Need an Attorney? We are Here.” For the most part, the lawyers sought to comfort families waiting for a loved one to clear immigration, tracked arriving flights, and collected information regarding who was being detained by officials or subjected to “enhanced questioning.” One lawyer said, “I am here to do anything. I just want to help.”[3]

For those who may have noticed, women attorneys appear to have composed the majority of airport volunteer lawyers.[4] In the following months, the attention of a vast network of individual attorneys, social welfare organizations, and non-profit legal organizations turned from the airports to preventing deportation of undocumented immigrants and litigating the Executive Order, along with other issues such as sanctuary cities, and the horrifying separation of children from parents.[5]

These events that seemed so unprecedented are part of a much longer history about restrictive immigration laws, organizations that advocated on behalf of immigrants, and the origins of the everyday practice of immigration law. Yet, the history of when and how the practice of immigration law arose has not been fully explored. In fact, the first professional organizations for immigration lawyers were not even formed until after World War II. The few works of scholarship that discuss lawyers who represented people with matters involving immigration law do not explore fully the role of philanthropic organizations as providing legal representation, and thus miss the crucial contributions of women social workers.[6] That women social workers were deeply involved in representing and providing advice to potential immigrants trying to enter the U.S. or those threatened with deportation is not surprising given the enormous role that women, who were not professional lawyers, played in the creation and provision of free legal aid to the poor in the nineteenth and twentieth century.[7]

This article examines the Chicago Immigrants’ Protective League, which was founded in 1908. The League was a grassroots social welfare organization in Chicago. Through its activism, its leaders became immigration law experts and disseminators of knowledge about immigration laws. It also provided free counsel to tens of thousands of poor migrants in a multitude of situations. Crucially, the League’s legal practice was not court based but rather on the ground where it provided advice to migrants and their families and represented migrants when dealing with the Bureau of Immigration. Always headed by women social workers who were deeply connected to Jane Addams’ Hull House, the women of the League created a robust model of immigration advocacy. Overtime, it combined the everyday legal representation of immigrants, the production of social science research and scholarship about immigration and immigrants, the lobbying of immigration officials and the federal government for better and less restrictive immigrations laws, and the provision of a variety of social services to immigrants. The League and its women, although certainly far from perfect, accomplished this work at a time of growing xenophobia and ever increasing restrictive immigration laws. It also did so during an era when only a handful of women were professionally trained lawyers.[8]

A close and thick reading of the League’s archival documents, manifests how the events of Donald Trump’s immigration policies has a long and painful history. U.S. immigration law has consistently been cruel, inhumane, arbitrary, and capricious. [9] Told from the ground up, one dramatically sees how immigration laws and practices were (and still are) like quicksand – changing and unstable— consistently thwarting the legitimate expectations of migrants, at times, leaving people in a legal limbo and at other times, destroying lives. In response, the League and others participated in creating a grassroots legal practice which was continually improvised as it quickly responded to changing laws, rules, policies and customs, and the needs of those trying to immigrate.

This article draws upon a vast and excellent scholarship on immigration law and policy while making numerous new contributions about the development of the practice of immigration law and the role of women legal providers.[10] In doing so, it examines how and why the League, primarily consisting of women social workers, became immigration law experts and advocates, and the role that gender played. On a micro, grass roots level, it examines the day-to-day practice of immigration law outside of the courts. The article highlights the at times close relationship the League had to immigration officials and how the League acted as legal intermediaries, often walking a tightrope between “accommodation and resistance” to the state.[11] Finally, it examines how an organization facing incredible social, legal, and political hostility to immigration continued to mobilize pro-immigration arguments and discourses. In answering these questions, the article, reflecting the League’s immigration practice, intentionally de-emphasizes formal law and instead examines how a series of people and institutions interpreted, lived, and experienced law in the everyday.[12]

By focusing on the League, always located in Chicago, this work further provides a unique geographical dimension to the history of the practice of immigration law. Many historians focus upon immigration stations at ports, whether Ellis Island, Angel Island, or even Philadelphia.[13] Newer scholarship focuses upon Mexican and Central American immigration and the creation and policing of the Mexican and U.S. border.[14] This makes sense as immigration officials’ decisions about admission to the U.S., as well as immediate appeals, occurred at such locations. At first, it seems strange to imagine Chicago as an early- twentieth-century hot spot of immigration law, but as we shall see, it was. The League became a sort-of immigration clearinghouse for the Midwest, and it had extensive contacts in the U.S. Bureau of Immigration, the State Department, other federal agencies, Ellis Island, and with national and international aid organizations. In part, this was due to the immense cultural capital of the women who ran the League and their institutional connections with Hull House and later the University of Chicago. Moreover, Chicago was not that far from the Canadian border and some immigrants from Europe attempting to reach Chicago, did so by crossing at the U.S/Canadian border.

Although historians generally tell stories about change over time, examining the League’s work demonstrates that the techniques that the federal government currently employs to deny people entry into the U.S. or to deport immigrants began much earlier. This is a continuing story of families torn apart, of unfettered bureaucratic power, and of how a specific organization intervened in a process that was part law, part policy, part custom and part bureaucratic discretion, which could inure to a migrant’s benefit or harm.

Part I of the article provides a brief history of the intense anti-immigration sentiment that lead to Congress enacting restrictive immigration laws before World War I. It goes without saying, that the practice of immigration law only developed in response to the enactment and enforcement of such laws. Part II intensely examines the origins of the League and the role that gender played in carving out a space in which the middle-class white women leaders of the League could claim an expertise in caring for and supervising poor white immigrant women. Part III discusses the pro-immigration discourse that the League used to counter intense social, legal, and political anti-immigration arguments and actions. The League’s leaders continually attempted to demonstrate the importance of immigration to the very identity of the United States. In part, the League did so by claiming an expertise, based upon first hand observation and study, of immigrant community life in the United States. Part IV of the article depicts and situates how the League, and other philanthropic organizations, engaged in and helped create the practice of immigration law. It argues that the League’s women workers, though not trained lawyers, were deeply involved in advising clients about the law and representing them in administrative immigration proceedings. Part V examines how, in the years before World War I, League workers quickly gained an expertise in handling matters involving immigration officials’ decisions to deny migrant women’s entry into the U.S. or begin deportation proceedings. In such cases, the League performed a type of balancing act between advocating for such women and earning the trust of immigration officials. Part VI explores the work of the League during World War I as it became legal interpreters and intermediaries between immigrant communities and the Federal government in connection with the Selective Service laws. It was through this work, that the League earned significant trust and began representing immigrant men on a wide scale. Such work also prepared the League to become experts in dealing with the bureaucratic administrative state. Part VII analyzes the League’s role in representing migrants after Congress passed highly restrictive immigration laws in 1921 and 1924. It examines both the League’s fury at such laws, and how such laws dramatically and without warning affected their clients. The final section describes the League’s day-to-day and mature legal practice as the 1924 law became fully enshrined. As the League documented, such laws often separated families and made reunification virtually impossible. This story, of course, deeply echoes the present.

I. A Brief History of Immigration Law Before 1917

To understand the emergence of the League, a basic knowledge of anti-immigration ferment in the U.S., and the body of restrictive immigration laws that it spawned is helpful. Rarely has there been a time between the 1870s and the present day, when nativist and anti-immigration sentiment did not exist in some form. Rallying cries of nativism were almost always present as low hums, and, at times, exploded. Elite forms of nativism such as Boston’s Immigrant Restrictive League spent years lobbying for immigrant literacy tests. Chinese and Japanese immigrants were long prohibited from seeking citizenship, and for long periods most were excluded from the country altogether. Vigilante groups engaged in multiple forms of violence against immigrants, including lynching. Discrimination in employment, housing, and various accommodations were long the norm. Many mainstream periodicals specialized in anti-immigration, anti-Chinese, anti-Semitic, and anti-Catholic hysteria. In a way that still resonates, politicians, writers, and others continually associated immigrants with crime and poverty. Moreover, by the first decade of the twentieth century, many elite and middle-class citizens argued that immigrants from Italy, Eastern Europe, Russia, Asia, and the Middle East were incapable of assimilation or self-governance. By the early twentieth century, pseudo eugenics had become part of mainstream science where politicians, journalists, and reformers maintained that certain races were genetically and biologically inferior to White Anglo-Saxon Protestants. At their most extreme, they suggested that immigrants would eventually populate the U.S., leading to the extinction of the white “race.”[15]

Given the current crisis over federal immigration policy in the United States, it can be difficult to grasp that the federal government was not particularly interested in running the day-to-day administration of immigration until the 1880s. Rather immigration was primarily left to individual states. Their focus was on preventing the entry of poor immigrants who might become financial drains.[16] States such as Massachusetts and New York supported their immigration apparatus by leveling a head tax on immigrants. Like so much else in U.S. legal history, such practice implicated federalism and in Henderson v. Mayor of New York, the U.S. Supreme Court found that such head taxes when levied by a state were unconstitutional.[17] This left states without funding to run immigration stations, and the federal government was forced to step in. Meanwhile, anti-immigration sentiment was growing, and Congress began facing political pressure to act.

For decades, whites had shown hostility and even murderous rage towards Chinese immigrants, especially in Western states. Whites claimed that the Chinese took away jobs from Americans, that Chinese women were prostitutes, and that Chinese immigrants belonged to criminal gangs that spread the opium trade. Responding to ever growing anti-immigration sentiment against Asians, Congress first passed the 1875 Page Act which prohibited the entry of Chinese, Japanese, and “Oriental” laborers who had entered into “involuntary” labor contracts, and the entry of Asian prostitutes.[18] Enforcement of the Act limited the entry of Chinese women whom officials automatically deemed prostitutes.[19] In 1882, Congress passed a more general immigration law based upon a conception of what immigrants were fit to live in the U.S and potentially become citizens. Specifically, it excluded immigrants who were or were likely to become public charges upon entering the U.S., along with “idiots” and “lunatics.”[20] That same year, it passed the Chinese Exclusion Act.[21] Historian Lucy Salyer writes that the Chinese Exclusion Act broke with past U.S. policy, which had seen the ability to change one’s homes and alliances as inalienable rights. The Chinese Exclusion laws were not tangential to larger immigration issues but would boomerang and after World War I serve as the basic framework for the nation’s immigration laws.[22]

Congress next passed the Immigration Act of 1891 which expanded categories of exclusion, extended the power to deport immigrants, and provided that federal officers would take charge of immigration. The Act created the federal Bureau of Immigration, which was headed by the Superintendent of Immigration and later the Commissioner-General of Immigration both under the Department of Labor and Commerce.[23] The Act also made the decisions of the Bureau of Immigration final, limiting the ability of migrants to challenge decisions in court.[24]

The next decades saw a growing list of potential immigrants excludable from the U.S. including beggars, people with physical or mental problems, polygamists, anarchists, convicted criminals, prostitutes, and the immoral.[25] Immigration law represented the public imagination’s great fear of immigrant dependency, criminality, and the inability of immigrants to fully assimilate. The ideal immigrant was to be an English-speaking, able-bodied, Protestant white man capable of autonomy and fully independent.[26] Yet the laboring classes also tremendously feared immigrants taking jobs from Americans. The Knights of Labor, with other labor unions, lobbied Congress to pass the Anti-Contract Law, which made an immigrant excludable on the basis of having a contract for employment prearranged before entering the U.S.[27] Thus immigrants had to walk a tight rope between demonstrating that they were able to support themselves and showing that they did not already have a prearranged employment contract.[28]

Congress also enacted deportation laws beginning in 1891. Deportation was originally aimed at those immigrants who were “likely to become a public charge” within one year of entry, but Congress then extended it to two, then three, and finally five years in 1917. Likewise, passage of the Mann Act in 1910 made immigrants identified as prostitutes, and those who trafficked in them, forever deportable.[29] These laws represented a growing distinction between the categories of citizens and aliens, and the reversal of the presumption that those who had been admitted into the country would be allowed to remain in the U.S.[30]

As Congress created a schema of restrictive laws, it also built the apparatus of federal administrative control. Ellis Island, newly opened, was controlled by the federal government, and immigration officials inspected potential immigrants for signs of physical or mental weakness, and interrogated immigrants to discern their ability to support themselves.

Line inspectors had substantial authority to deny immigrants entry into the U.S. Contemporaries as well as historians emphasize that inspectors were often overzealous, understanding their role to hinder rather than support immigration.[31]

The Immigration Act of 1893 created Boards of Special Inquiry at each U.S. seaport entry station that held hearings to determine whether a line inspector’s decision to exclude a potential immigrant would be upheld.[32] Each board consisted of three rotating members chosen by the local commissioner of immigration. One Treasury Department circular from 1907 provided that the hearing would not be public but that, at the discretion of the commissioner, the immigrant could have a friend or counsel accompany him or her.[33] Some decisions were made by such Special Boards in a couple of minutes, and others could take days as the Board investigated the potential immigrant.[34] Like line inspectors, these boards had immense discretion. The composition of the boards was also problematic insofar as line inspectors sat as judges. Appeals from board decisions could be taken to the Commissioner of Immigration and then the Secretary of the Treasury, later the Secretary of Labor.[35] Giving immense berth to the Immigration Bureau, the U.S. Supreme Court in Nishimura Ekiu held that federal courts could not review an immigration official’s factual determinations regarding the exclusion of a potential immigrant and that an excluded potential immigrant did not process constitutional rights to due process.[36]

Between the 1890s and 1917, most immigrants (excluding Chinese and Japanese who largely were not permitted to immigrate) who were denied permission to immigrate to the U.S. by officials fell into the very broad and ambiguous “likely to become a public charge” provision. It functioned as a catchall and, as League leaders argued, was used by immigration officials “to exclude anyone who seemed to them undesirable.”[37] Thus, by the early twentieth century, the federal government had put into place the apparatus of the control of migrants, which, as we shall see, continued to grow and become increasingly bureaucratic.

II. The Immigrants’ Protective League: The Beginnings

The Immigrants’ Protective League was a response to the vast numbers of new immigrants streaming into Chicago. Like so many cities across the world, immigrants fleeing poverty, war, and oppression had long settled in Chicago. Yet it was in the 1890s that the immigrant population began to swell. Between 1910 and 1919, 362,756 new immigrants arrived in Chicago. This number alone, however, does not fully convey the speed at which immigrants were arriving in Chicago: in 1892, 46,102 immigrants entered the U.S. headed to Illinois; in 1907, that number was 104,156, and in 1913, over 107,000.[38]

This mass arrival of new immigrants to Chicago triggered not only hostility and fear, but also gave rise to a vast number of social service organizations, in part intended to aid immigrants as well as to assimilate and Americanize them.[39] As historians have long argued, such organizations often engaged in forms of social control, imposing white Protestant middle-class values of work, discipline, appropriate gender roles, domesticity, and sexuality upon poor immigrants.[40] However, the most progressive organizations, such as Chicago’s Hull House, also celebrated cultural pluralism.[41]

Jane Addams founded the Hull House settlement in 1889, and it would become one of the best-known and celebrated settlement houses. On their most rudimentary level, settlement houses were residences established by elite and middle-class women and men in poor and primarily immigrant neighborhoods.

Some settlement workers lived in the settlement house and others worked there. Settlement houses leaders attempted to provide needed services to the community as they arose and often experimented with creating programs that they hoped would eventually be sponsored by the government. Over the years, Hull House provided a cafeteria, English classes, cooking classes, and a host of other educational opportunities for children and adults. In addition, it built playgrounds, ran summer camps, sponsored lectures, art exhibits, and plays, taught vocational skills, and provided a physical meeting space for a wide range of organizations including labor unions and at times striking workers. Residents of Hull House were also some of the first people to attempt to study the lives of immigrants and to lobby for minimum wages and maximum hour laws, tenement regulation, juvenile courts, and other progressive reforms. Hull House became a vibrant center for political, legal, and social reformers, and it hosted some of world’s leading intellectuals, both male and female. [42] The women leaders of the Immigrants’ Protective League all had spent considerable time at Hull House and were some of Jane Addams’ closest confidants.

The original idea for the Immigrants’ Protective League grew out of Hull House and the work of the Chicago branch of the Women’s Trade Union League. The WTUL was a cross-class organization of women, which advocated for a broad range of labor reforms for women workers. The WTUL had established a committee to study the issues affecting young women who immigrated by themselves to Chicago, finding that they (in common with other immigrants) confronted a variety of problems that went well beyond the WTUL’s mandate or capacity to address.[43] In response, Jane Adams and Sophonisba Breckinridge (who was both a member of the WTUL and a Hull House resident) advocated for the creation of the Immigrants’ Protective League. Using the vast contacts possessed by Addams and Hull House, they called upon its most loyal supporters to join the League’s Board.[44]

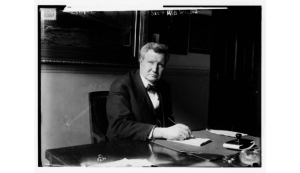

Officially founded in 1908, the early leadership of the League included lawyers, judges, reformers, businessmen, and social workers, but it was Grace Abbott, Edith Abbott, Sophonisba Breckinridge, and later Adena Rich Miller who for decades spearheaded and engaged in most of the League’s work. Grace Abbott for years filled the role of executive director and Breckinridge for decades was an active officer and board member. Grace Abbott, born and raised in Nebraska, moved to Chicago to join Hull House in 1907, and earned a master’s degree in political science from the University of Chicago. At Hull House, she met Sophonisba Breckinridge, who hailed from a prestigious Kentucky family of politicians. Nisba (as she was called) held a law degree and a PhD from the University of Chicago and was a pioneer in the professionalization of social work, first teaching at Chicago’s School of Civics and Philanthropy and then founding, with Edith Abbott, the University of Chicago’s School of Social Science Administration.[45]

Impressed by Grace Abbott, Breckinridge and Addams quickly recruited her to be the director of the Immigrants’ Protective League.[46] Joining Abbott and Breckinridge, and in their own right playing significant roles in the organization, were Julian Mack, first a judge in Illinois and later a federal judge, and University of Chicago law professor Ernst Freund.[47] Later Grace’s sister Edith Abbott would become an active member of the League and an expert in immigration.[48]

True to its roots in the WTUL, one of the League’s earliest missions was “protecting” young immigrant women traveling from Ellis Island to Chicago. Using well-worn tropes of young women’s virtue and vulnerability, the League claimed that countless young new immigrant women mysteriously disappeared before reaching Chicago.[49] The organization’s mission thus leveraged the titillating and wide-spread panic about white slavery and the fear that innocent young white women immigrants were lured into prostitution through either trickery or physical force. Historians have long debated whether such panic was grounded in facts or a cultural hysteria arising from the fear of immigrants, urbanization, new forms of amusement, and greater freedom for women.[50] Whether accurate or not, such anxiety served the League well. In the gendered separate spheres of early twentieth-century reform, the well-being of young women fell within a women’s sphere of responsibility.[51]

Lurid tales aside, the League’s concerns were legitimate, as young women leaving Ellis Island often had little money and many did not speak English. Traveling by train from New York to Chicago made such women vulnerable to harassment. The journey was complicated with train schedules continually changing, and railroad personnel were not always helpful. The League constantly harangued the railroads and officials at Ellis Island to provide some sort of security for such women and eventually the League obtained manifests of women expected to arrive in Chicago. The League’s leaders often claimed that it was their job to “protect” and “supervise” such women, as the government, and railroad officials failed to do so. [52] Such work represented a type of Progressive era social feminism that saw poor women as having special needs, which could be met best by middle-class women who would provide a type of informal guardianship that bordered on social control. It also mapped on to Progressives’ desire for orderly processes, which the mass arrival of immigrants at train stations, at all hours of the day and night, did not meet.[53]

The League’s early day-to-day work involved meeting immigrants arriving from Ellis Island by train, directing them to legitimate taxis and away from runners, locating lost relatives and luggage, finding the correct addresses of friends and family, and locating shelter for those immigrants who literally had no place to go.[54] Though seemingly simple, this was not, as Chicago’s train stations were hectic, trains arrived hours, if not days late, addresses were not standardized, and slips of paper with names and addresses of friends and relatives could be lost in translation, or ink washed away. Immigrant families often moved, and letters overseas could easily cross.[55] The League’s workers through their contacts in various immigrant communities, in part coming from Hull House’s networks, as well as numerous immigrant benevolent associations, became experts of the everyday.

Visiting the homes of newly arrived immigrant women absorbed much of the League’s time. Such “visiting” was central to the emerging profession of social work, as well as the older tradition of friendly visits, whereby a middle-class volunteer, often a woman, would stop by the homes of the poor. Here, the League attempted to ensure that, in the League’s (less than objective) opinion, a woman lived in a safe and appropriate home. It often perturbed League workers that single women lived in housing with groups of unrelated men and the League emphasized the potential danger such women faced while recognizing its commonality.[56]

Popular culture has long made fun or farce of the prudery of early-twentieth century social reformers, but the reality was more complicated. Women like Grace Abbott and Breckinridge did not condemn pre-marital sex as a sin or in and of itself immoral. Rather, they were deeply concerned with the consequences of young women’s sexual activities. With little access to birth control, pregnancy was always a risk. Moreover, cultural mores were such that unmarried women who became pregnant were seen as immoral, making their lives that much more difficult. Given the structural discrimination of the workplace and the jobs available to women, supporting children on a women’s wage alone was extraordinarily difficult. Moreover, they worried about what constituted a young woman’s consent to sexual activity, given the very young age and vulnerability of some immigrant women.[57]

The League’s work, however, went well beyond concerns about sexuality. League visitors would inform women of English classes, potential employment, where to seek medical care, the importance of sending children to school, as well as other resources and advice that might help with what we would now call immigrant resettlement.[58]

The League, and its related institutions, created a vast net for immigrants that was both a safety net and one in which a person could be ensnared.[59] For example, the Abbotts and Breckinridge surveyed and researched immigrants, and then using such information to write articles and books about the necessity for a wide variety of reforms, which the League, along with Hull House and other women’s institutions, then lobbied city and state elected officials to pass. Among its priorities was the enforcement of truancy laws, laws prohibiting underage employment, and maximum hours laws for women. Although these reformers whole-heartedly believed that such laws would help immigrants ultimately better their lives, they also, at times, conflicted with the wants, needs, and realities of individual immigrants.

Among the League’s greatest concerns were employment agencies often run by second generation immigrants. The League complained that new immigrants might pay an employment agency for work that either never materialized, or which paid less than the fee charged by the agency. Such agencies also transported workers hundreds of miles from Chicago for low wage temporary work after which the immigrant was left stranded.[60] At a time in which people did not recognize or discuss sexual harassment, the League was concerned about the treatment of immigrant women by employers. It sought to prevent employment agencies from placing young women in certain positions such as scrubbers and dishwashers in certain Chicago hotels or waitresses in restaurants where they were not “morally safe.”[61] Likewise, it was worried about the unfettered power of factory supervisors. Abbott wrote, “American foremen in factories sometimes abuse a power which is more absolute than any man should have the right to exercise over others, and on threat of dismissal the girl submits to familiarities which if they do not ruin her cannot fail to break her self-respect.” [62] The League even attempted to prosecute some of those agencies that sent women to jobs where they faced harassment, but it was continually unsuccessful. In the absence of legal protection, the League publicized such potential dangers, and the names of unscrupulous employment agencies and employers, in a variety of foreign language newspapers.[63] Eventually, the League drafted and lobbied for a law regulating employment agencies which was passed by the Illinois legislature but inadequately enforced.

III. The League’s Discourse in Favor of Immigration

So far, the League’s actions do not drastically differ from other left-leaning Progressive era organizations working with immigrants. Yet the discourse and tone that the League used to describe immigrants and immigration did in fact set it apart from many other Progressive organizations, which tolerated immigration and immigrants but did not view either as a social good or crucial to America’s identity. Instead, amid significant anti-immigration sentiment, which increasingly painted immigrants as posing a danger to the political economy and well-being of the United States, the League made a powerful case as to why immigration was at the heart of national identity. It argued that immigration strengthened the U.S. and that the country and its citizens had an affirmative duty to assist new immigrants.[64] Equally important, over the years it sought to counter, with facts, each of the arguments against immigration.

Judge Julian Mack, one of the founders and the first president of the League, spoke of his own grandfather and great grandfather as Jewish immigrants escaping persecution and the bond that he felt with the thousands of Eastern European Jews who were immigrating to the United States. He also expressed his outrage at those who engaged in anti-immigration action.[65]

At one IPL event, Judge Mack introduced Charles Nagel, former Commissioner of Labor, who was to give a speech.

Mack cunningly announced, “Tonight Mr. Nagel is going to address us on the subject of ‘Americanization.’ Whether he is going to tell us about the Americanization of the Immigrant {sic}, that is so much needed, or about the Americanization of the native born, which is so much needed, I do not know.”[66] Here, Mack humorously deconstructed a singular idea of what or who an American was and the characteristics that made Americans. Mack later spoke of how immigrants already embraced American democracy– an ideal that those born in America often took for granted.[67] He further rejected the metaphor that America was a melting pot of immigrants. “A better simile,” he wrote, “is that the American nation is the harmonious orchestra in which each of the nationalities of the old world is contributing its share in unison to the complete symphony.”[68] Mack, like other IPL leaders, imagined immigration as a source of renewal for the nation and believed that citizens and the state had a set of obligations to the immigrant. He propounded, “The increased duties that the immigrant brings to us are often urged as a reason for keeping them out, and it is an argument; but the tremendous value of the immigrant when we properly perform our duties toward him far outweighs the material cost of the performance of these duties.”[69]

Grace Abbot held similar views of the importance of immigration to the wellbeing of America, which derived from her broad sense of humanism. She wrote, “The League was organized not only to serve all nationalities and all creeds, but to try to break down the forms in which racial injustice so frequently appears in the United States. All the members of the League have in a sense subscribed to the doctrine of Garrison that our countrymen are all mankind, and personally, I feel grateful that because of immigration this is so literally true.”[70]

Grace Abbott, as early as 1916, was one of the foremost national experts on immigration, and especially immigrant women, and provided Congressional testimony opposing restrictive immigration laws.[71] She, and other League leaders used every avenue at their disposal to broadcast their support of immigrants and immigration. The League repeatedly reminded its audience that they too, whether they were Mayflower descendants or had ancestors who immigrated as part of the Irish and German wave of immigrants in the 1840s, had immigrant roots. Abbott likewise wrote of the violence and persecution that led people to immigrate and saw it to be even worse than that endured by the Puritans. It was hypocritical, she argued, to celebrate the Puritans while refusing to recognize the plight of the modern immigrant.[72] In essence, Mack, Abbott, and the other leaders of the League figured the relatively free flow of immigrants into the U.S. as part of a broad social contract, which was tied to the essence of what made America exceptional.

The League staunchly and consistently opposed Congressional legislation that would have required immigrants to pass a literacy test for admission into the U.S., arguing that such a requirement was unjust and irrational as it would bar some of the very people who were most in need of admission. One reason people immigrated to the U.S., the League argued, was to allow their children to attend public schools, something unavailable in their native countries. Flipping the Congressional bill on its head, the League propounded that a parent’s desire to educate their children or themselves was evidence that a potential immigrant already embraced American values. The League further loudly opposed immigration restrictions that denied admission to people with physical deformities, believing that a “person’s character, high ideals” and “ambition” were more indicative of potential citizenship than a physical handicap.[73]

In Congressional testimony, Abbott also argued that any literacy test would unfairly affect women, especially Southern and Eastern European women, who had few opportunities to attend schools or otherwise gain literacy “due to prejudice against the education of women.”[74] She explained that even an exemption for daughters and wives immigrating with a literate male head of the household would do nothing for women immigrating alone, many who hoped to save money and later help other family members to immigrate.[75]

Opponents of immigration had long argued that poor immigrants would become a financial drain upon the state and lobbied for stricter immigration laws. The League directly countered: “The records of public and private relief agencies bear ample testimony to the fact that [the new immigrant] makes a great effort to realize his ambitions during what ought to be the most difficult period of his residency in America.”[76] They further pointed to a study, with which the League was involved, showing that out of 17,449 cases handled by Chicago’s United Charities, only 177 involved immigrants who had been in the United States less than three years. Immigrant poverty, they argued, was primarily not the fault of the individual immigrant but of the government itself. This included the state’s failure to enforce housing and sanitary regulations, the lack of minimum wage and maximum hours laws, inadequate health care and industrial safety, and a failure to regulate banks and money lenders. The League also pointed to the disheartening fact of racial and sex discrimination against immigrants and how that affected their wage-earning potential.[77] One IPL report apologized to immigrants for “community indifference” in response to the discrimination and poverty they faced.[78]

Likewise, the League propounded that to the extent immigrants had difficulty in adjusting to life in the U.S., it was structural, not personal, hurdles that stood in the way. One of its studies found that adult English classes for immigrants on the South Side of Chicago were poorly enrolled and had a large dropout rate. Many blamed this on immigrants’ disinclination to learn English or lack of intelligence. Yet the League learned that the steel mills, the largest employers in that area, had workers on twelve-hour evening shifts every other week. In other words, a standard schedule made it impossible for workers to regularly attend school. The League suggested that classes needed to meet the needs of the immigrant worker, by taking into account busy and slow seasons, and –an even more radical idea– providing teachers who were bilingual. Similarly, the League advocated for visiting home teachers for mothers caring for young children.[79] This strong emphasis on the need for educational opportunity for adult immigrants continued to be a demand of the League well into the 1930s.[80]

The trope that immigrants are responsible for large numbers of crimes is a centuries-old staple of nativists’ attempts to limit immigration.

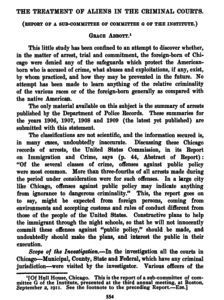

The trope that immigrants are responsible for large numbers of crimes is a centuries-old staple of nativists’ attempts to limit immigration. To counter this, the League published statistics demonstrating that immigrants in Chicago committed fewer crimes than the non-immigrant population. Using nation-wide statistics from the Commissioner-General of Immigration’s Annual Report, Abbott stressed that immigrants from Western Europe committed more crimes than those from Southern and Eastern Europe, although immigrants as a whole committed fewer and less serious crimes than the white native born.[81] Thus the League once again countered fiction with fact.

Abbott and the League’s leaders further argued that immigrants were often police targets who were unfairly arrested and shoved into a criminal court system where they could not defend themselves or even understand court proceedings, as translators were not provided. The League told endless stories of its workers acting as translators and advocates for non-English speaking immigrants wrongfully, even “illegally,” arrested. Abbott publicly blamed a blatantly racist, ineffective, and corrupt police force, citing instances where police murdered young immigrant men or continually arrested immigrants that they knew to be innocent.[82] Due to poverty, such immigrants were often unable to make bail, spending months in jail awaiting trial, and then facing a hostile and prejudiced judge and jury. The League sought to convey the havoc that came of such imprisonment and how it flew in the face of purported American understandings of justice and the rule of law. At best, such experiences “humiliated” an immigrant. Worse, it could result in imprisonment and deportation.[83] Writing in 1917, Abbott was clear that blatant police prejudice against immigrants was far more dangerous to the public welfare than the crimes in which immigrants engaged.[84]

Finally, Abbott, in Congressional testimony, directly addressed the long-running argument that immigrants took jobs away from Americans. She sought to show that the well-being of the economy was unrelated to the number of immigrants who entered the country. Years of small immigration, she explained, did not translate into more jobs or higher wages for Americans. She maintained that the idea that the supply and demand of workers dictated wages was “an exploded theory of the last century.”[85] Wages were determined by the demand that employers made for profits.[86] Thus unemployment and low wages were the result of unregulated capitalism, not immigration. She boldly claimed that those politicians who supported immigration restrictions, under the pretense of supporting labor, seldom voted for legislation that would “better the conditions of working men and women.” Rather, superficial support of labor through immigration restriction was “a cloak to conceal a hostility against certain races” as well as religions.[87]

As open minded and imaginative as the League’s leaders could be, they were far from perfect and could engage in racist behavior. Although the League spoke of immigrants and immigration in universal language, League leaders did not condemn the Chinese exclusion laws, and tried to side step the issue when directly confronted. During Abbott’s Congressional testimony in 1916, she was asked whether she supported any immigration restriction. In part, she responded that she supported the immigration of those who were “fit” but continued with the following caveat: “While I have had a great deal of experience with European immigrants, I have never had any experience with oriental immigration.” Upon further questioning she continued that she supported Mexican immigration and would personally have “no objection to working side by side with a Hindu” but she again qualified her answer. “I want to say again that I do not know at first-hand the racial difficulties that are charged to the Hindu, the Chinese, or the Japanese immigrant.[88] Indeed the League did not handle the cases of Chinese immigrants nor did it speak out against their exclusion. Rather, the League had its own racial hierarchies, and the reality is that it spent most of its resources and time working with European immigrants as well as those from Turkey, Armenia, Syria, and Mexico. Although it was often unclear what immigrant groups were “white” during the first part of the twentieth century, the League can be said to have underwritten a type of whiteness. This whiteness was broad, encompassing Jews, Turks, Armenians, Bulgarians, Southern and Eastern Europeans, Persians, Syrians, and Mexicans, but it was nonetheless whiteness.

What the League did do, even if incompletely and with inexcusable failures, was to carefully dissect many of the typical arguments that people made (and astoundingly still make) for restricting immigration. Stripped bare, Abbott called restrictive immigration laws what they were – racist and prejudiced. The League leaders not only believed in the crucial importance of immigration to the prosperity of the country, but they also deeply believed that facts produced by experts themselves could change people’s minds. Such belief may have been wrong.

IV. The Landscape and Practice of Immigration Law

In addition to advocating against restrictive immigration laws and creating arguments in favor of immigration, the League soon explicitly interpolated and presented itself as legal advocates for individual immigrants as well as cultural and legal brokers. One publication announced, “The Immigrants’ Protective League… may be called upon for advice or service in the immigration or naturalization difficulties of the foreign born of Chicago.”[89] The League aggressively reached out to immigrant populations, advertised its services in a variety of publications directed at immigrants, and circulated announcements and interpretations of new immigration laws, rules, and practices. So too did it speak to a larger audience, demonstrating the profound, at times horrific effect such immigration laws and their enforcement had on individuals, families, and communities.

The League was certainly not the first group of advocates to provide legal assistance to immigrants. The first organized legal challenges to immigration laws that discriminated against Chinese immigrants were undertaken by Chinese merchants and the organization that they had formed – the Chinese Six Companies. Lawyers hired by that organization were some of the first to contest the Chinese Exclusion Act, the vast delegations of power to immigration officers, and the denial of entry to Chinese immigrants.[90] The attorneys who litigated these appellate cases for the Six Companies were often elite white male lawyers who intentionally brought test cases in court.[91] At the turn of the century, there were also a handful of lawyers on the West Coast who represented Chinese immigrants in habeas corpus proceedings in federal court.[92] These were lawyers who worked for fees, and their practices were court based.

Likewise, historian Louis Anthes has demonstrated that as early as the 1890s, some European immigrants denied entry to the U.S hired attorneys to represent them. These lawyers were themselves primarily immigrants who received their law degrees from an expanding number of night schools.[93] Such lawyers, whom elites considered marginal to the profession, would at times bring federal habeas corpus proceedings to contest immigration officials’ denial of entry. They might also appear at the Special Board of Inquiry hearings that determined whether to uphold an immigration officer’s initial decision to deny entry. Anthes argues that given the discretion of immigration officials, lawyers primarily played cameo roles and were rebuffed by such officials. He concludes that most attorneys were not repeat players, who took such cases day-in and day-out and specialized in immigration law. With a few exceptions, the occasional immigration case augmented their regular legal practice.[94] Anthes also finds that in the 1890s immigrants represented by attorneys in Board of Inquiry matters lost their cases in higher percentages than did immigrants without attorneys.[95]

Numerous benevolent societies were also situated on and near Ellis Island and some provided immigrants with representation during board hearings. A number of Jewish organizations excelled in this area, with probably the most well-known being the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society and the National Council of Jewish Women.[96] Yet, at times, government officials viewed ethnic and religious organizations as suspicious and even as lawbreakers in their desire to aid immigrants. In contrast, League leaders, in a racist world, brought the capital of being white Protestants.[97]

Not having a traditional attorney but a legal advocate such as the League may have produced better outcomes for those detained. Unlike trained attorneys, the League was not constrained by traditional legal arguments, were repeat players, did not attack the administrative process as a way of winning individual cases, and did not automatically approach immigration officials as adversaries. Moreover, the League’s workers, almost all women, must have created the appearance of a softer, charitable endeavor, intended to, at least superficially assist immigration officials in reaching the correct decision rather than engaging as direct adversaries. It is not that the League refrained from offering hard-edged critiques of the immigration process, officials, and policies, but they did so outside of the administrative process, in annual reports, articles, studies, and books.[98]

Receiving favorable results in Board of Special Inquiry proceedings or on appeal to senior officials was of dire importance to the potential immigrant, given the substantial deference of federal judges to such decisions. Historian Lucy Salyer writes that between 1891 and 1906, 164 habeas petitions were filed in the Southern District of New York, which had jurisdiction over Ellis Island. Of these, only 16 were granted.[99] Thus the vast majority of contested decisions of immigration line inspectors were won or lost on the administrative level.

As immigration restrictions increasingly became harsher, the League created and engaged in the mature practice of immigration law on the administrative level. Practice, here, has multiple meanings.

As immigration restrictions increasingly became harsher, the League created and engaged in the mature practice of immigration law on the administrative level. Practice, here, has multiple meanings. The League’s work involved participating in the creation of a legal specialty, but practice also entails the day-in and day-out repetition of a multitude of tasks that eventually become normalized and ingrained in the institution. The League also became expert at improvising when confronted with shifting and unstable legal terrains. Indeed, the League sought to become involved in the immigration process as early as possible, ensuring affidavits and papers were in order before an immigrant passed through immigration, and then immediately locating immigrants who were detained, providing documents and evidence for the Special Board, and automatically appealing adverse decisions.

The League, as mentioned, was not the only philanthropic agency to engage in the representation of immigrants free of charge. Multiple agencies were located on Ellis Island and they proliferated along with the passage of immigration laws. The League worked with many of these organizations but also harbored some distrust of them. Edith Abbott described such organizations as “zealously” functioning as “attorneys for the defense.”[100] This comment was not entirely laudatory. Her criticism was that such organizations were parochial and provided help only to co-nationals or co-religionists.[101] This was incongruous with the League’s ideal of secular cosmopolitanism.[102] Moreover, some of the advocates for such organizations, the League complained, were too lawyer-like and failed to adopt to the informal administrative space in which cases quickly unfolded, evidentiary rules were absent, and there was little due process. Whether or not the League’s leaders realized it, this was the type of administrative tribunal that they, in other contexts, had helped or sought to build in juvenile courts, workers compensation tribunals, and dozens of state and municipal authorities such as housing, factory, and health regulators.[103] Where lawyers continually challenged hearings in which affidavits and written documents were used in place of testimony and cross-examination, this was a practice preferred by the League, and allowed it to operate from Chicago.[104]

More troubling, Abbott’s remarks may have been directed at some of the Jewish immigration agencies, which were run and staffed by primarily male lawyers. Her comments perhaps give off a slight whiff of anti-Semitism.[105] But, like it or not, the League often had to cooperate with various Jewish, Catholic and ethnic-based agencies.[106] Family members in Chicago of people detained on Ellis Island would at times call upon multiple agencies, and organizations in New York might need evidence located in the Midwest. Likewise, the League often needed a person on the ground on Ellis island who could find clients and quickly relay messages. When given a choice, the League worked closely with representatives of the Young Women’s Christian Association who were located on Ellis Island. In other words, its preferred colleagues were women like themselves.

To fully understand how and why the League represented immigrants and the types of arguments that they used, one must grasp its leaders’ underlying ideology. Its leaders, composed primarily of social workers, continually spoke in the register of the importance of families as the core unit of society.[107] Ideally such families would consist of a male breadwinner who could adequately support his wife and children, and a mother who could devote significant time to her children, even if she too was a wage earner. In part, this mapped on well to the underlying structure of immigration law, as well as traditional middle-class values. But as immigration law played out on the ground, families were often separated, leaving husbands without wives, wives without husbands, and children without parents. This provided an ideal space for social workers to construct their role and work as immigration experts interested in the general well-being of society.

Unlike some women’s organizations that provided free legal aid to the poor, the women of the League did not fashion themselves as lawyers, and even sought to differentiate themselves from attorneys. The League claimed that lawyers overcharged their clients on immigration matters, lied, did sloppy work; and, at their best, did not have the expertise of the League. League leaders made sure to fashion the League as a purely philanthropic organization, led by women, and conducted solely in the interest of the public good. Their advice and representation, they maintained, was free of the self-interest that marred lawyers, especially the types of lawyers who represented clients in immigration matters, primarily immigrants themselves. Chiding lawyers, the League expounded, “Records must be located in distant communities or witnesses sought and selected and depositions made. . . it is often mishandled by lawyers, owing partly to the fact that immigration rulings change so often. These processes offer marvelous opportunities for exploitation. Sums up to $34.00 have to our knowledge been paid for comparatively simple papers, up into the hundreds of dollars where it was claimed that ‘interests would be secured in Washington.’ Or relatives brought almost by return boat. Sometimes they could have been brought anyway and in other instances [were] entirely inadmissible.”[108] Whether or not accurate, or another sign of such women’s elitism and preference for other Anglo-Saxon Protestants, the League saw lawyers who represented clients in immigration matters as often exploitive, preying upon immigrants’ fears and making promises that could not be met.

The League went as far as contacting the Chicago Bar Association to report the unethical activities of a number of lawyers representing clients in deportation cases. The League claimed that bar officials disclosed that almost one quarter of complaints that they received were from clients of lawyers working on immigration matters. Bar officials also supposedly agreed to refer immigrants in need of immigration assistance to the League rather than to private lawyers.[109]

Even when lawyers were not engaging in blatantly unethical conduct, the League complained that some attorneys failed to attend to their client’s needs. Concerning one case, the League wrote, “The matter dragged for a long time; the lawyer would forget about the case unless the I.P.L. reminded him of it.”[110] At times clients went to the League after they had already hired a lawyer and the League often advised the person to dismiss his or her lawyer and allow the League to handle the matter.[111]

V. The League, Women, and Immigration Law Before WWI

The League’s vision of the cosmopolitan polis, and the supposed need to protect immigrant women, both informed the reforms that the IPL lobbied for and was the backdrop for its work as a legal advocate. Early on, the League began assisting young European women whose entry to the U.S. was denied by immigration officials. Such denial was usually on the ground that the woman was “likely to become a public charge.” This provision was consistently used by immigration officials to deny entry to unmarried European women. Officials required such women to demonstrate that there was a person (preferably a male relative) who would be “able, willing, and legally bound to support them.”[112] In some cases, even if such a woman had funds to support herself, immigration officials would not allow entry until a male relative appeared to “claim” the woman. If such a man appeared suspicious, immigration officials might still refuse the woman entry. Neither laws nor even regulations required the presence of a male, but immigration officials’ discretion was so vast in regard to the public charge provision that this became an ongoing practice.[113] One scholar writes that unaccompanied women were essentially treated like wards of the state and immigration officials could indefinitely detain women. At times, high level officials justified such detention on the grounds that they were protecting such women from white slavery.[114] Likewise, unmarried pregnant women and unmarried mothers with children could be denied entry on the basis that they were prostitutes, immoral, or once again likely to become a public charge.[115]

Migrating women had some sense of this practice and were not passive. Some arranged for male acquaintances to claim that they were fiancées or relatives in order to gain entry to the U.S. At times this worked, and at other times officials caught on to the plan.[116] Other women legitimately believed that they were engaged but fiancées might be no-shows.

Occasionally immigration officials would draw upon the League’s “expertise” and knowledge about European women immigrants, and ask for its assistance when investigating and determining whether a single woman might become a public charge or was “immoral.” In such cases, the League walked a sort of tightrope between advocating for the detained woman while also appeasing immigration officials. In other cases, the League might become involved when relatives in Chicago of a woman in detention, or such women themselves applied for its help. The activities that the League engaged in on behalf of such women were simultaneously extraordinary and troubling.

A case illustrating some of these complex dynamics involved Maryana Rosozki an eighteen-year old from Poland. In February 1914, she attempted to cross the Canadian border but was detained by immigration officials while the Board of Special Inquiry conducted an inspection of her uncle’s home where she intended to reside. Officials found the home unsuitable due to “crowding and unsanitary conditions.”[117] The Inspector then called upon the League and requested that it find live-in domestic work for the woman and “supervise her.” The League agreed, and Maryanne was permitted to enter the country and travel to Chicago where the League secured such a placement. Over the ensuing months, the League repeatedly visited the uncle’s home and the home where the young woman worked and resided, hoping to one day convince immigration officials that the uncle’s home was in fact suitable.[118]

What is shocking about this case is the absence of any specific law or legal provision either allowing the League’s intervention or granting officials the power to condition entry on the woman working and living only at a specific location in a specific job, regardless of her desire or consent.[119] This practice of immigration officials requiring a detained white woman to serve as a live in domestic was not unusual and stretched back to the 1880s.[120] Here, the much vaunted American liberty to choose how to use one’s labor and whether or not to enter into a contract was simply ignored by immigration officials.[121] Discussing this practice, historian Andrew Urban writes, “Rather than liberating white women from dependency rooted in servitude, the state asserted its authority to intervene in and produce these relationships.”[122]

Maryana’s class, gender, and immigrant status allowed immigration officials to dictate her employment and living conditions, and the League, essentially acting as probation officers, and, even an arm of the state, readily agreed to such conditions. By the 1910s, immigration officials’ practices encountered criticism as some claimed that officials sent such women into households without a thorough inspection or that they had been released into the hands of religious missionaries, or for-profit employment agencies.[123] In contrast, the League’s impeccable reputation as a secular philanthropy run by women allowed immigration officials to avoid criticisms that such immigrant women may have been sent to inappropriate placements or that any money had changed hands.[124]

Troubling, however, is that the League and immigration officials were so fully immersed in an ideology that saw live in domestic work as ideal for white immigrant women. In such work, the servant, theoretically supervised and guided by a respectable and middle-class woman, would both learn a skill and adopt normative middle-class American values. In exchange, the employer would receive inexpensive white domestic labor, at a time when many middle and upper-class women believed there was a servant shortage of especially white women domestics. Yet, as historians have demonstrated, many young immigrant women did not want to work as domestics as it provided them with little freedom compared to factory work. This was, of course, exactly why the League and officials found such employment suitable.[125] Whether or not such young women wanted to be live-in domestic or whether they should have the freedom to choose their own employers and bargain for wages was simply beyond the point.[126]

A similar though unsuccessful case involved Rosa Markewicz, another young Polish woman detained at the Quebec/U.S. border because immigration officials found that her male relative’s home (where she intended to stay) had too many male boarders – official called “a non-family group.” Officials believed that this could cause Rosa to become immoral. Rosa’s relatives asked the League to intervene and convince immigration officials to allow Rosa to enter the country. The League wrote first to the Board of Inquiry, which denied its request, and then appealed the Board’s decision to the Inspector in Charge and eventually the Secretary of Labor. Although the modern lawyer often thinks of appeals as requiring official and formal legal briefs, the League’s appeals were written as relatively informal letters that primarily emphasized facts. In Rosa’s appeal, the League highlighted that the relatives were from a “good family,” were employed, and could easily support the woman. It also assured officials that the League would monitor the situation. Nonetheless, immigration officials refused entry and Rosa was forced to return to Poland.[127] In another League case, three Polish girls were not allowed to enter the U.S. in 1914 despite the existence of relatives in Chicago and the League’s guarantee of close supervision and placement in live-in domestic work.[128]

It was clearly difficult to gain admission to the U.S. as a single woman, but it was even more difficult as an unmarried pregnant woman. The League specialized in such cases. Take the matter of seventeen-year old Anatasia Bazanoff who attempted to immigrate from Russia, and was detained at Ellis Island as likely to become a public charge. Immigration officials suspected that she was pregnant; Anatasia denied it. In August 1915, the brother of Anatasia, already in Chicago, approached the League for assistance in procuring her release and the League intervened. Immigration officials would only release Anatasia on the condition that a male family member post a bond, backed by property or cash guaranteeing that Anatasia would voluntarily leave the country if she became a public charge within one year of entry. The family did not have the resources to put up such a bond.

Anastasia’s long detention caused her sister (also in Chicago) to become distraught. The sister wrote to the League, “I am thinking all the time about [my sister], and I am crying. I can’t eat, I can’t sleep. My sister will die there [Ellis Island] and I here. I can’t live without her.”[129] Such a letter, not all that uncommon, is just a snippet of the distress that so many immigrant families experienced when relatives were detained or refused entry.

In the meanwhile, the League attempted to persuade the Inspector in Charge of Ellis Island to release Anatasia on an unsecured personal bond from the brother. It also proposed that the League supervise Anatasia, place her in domestic work, and report to immigration officials on her progress. The Inspector rejected this proposal. Three months later, with Anatasia still in detention, doctors certified that she was in fact pregnant and continued her detention. One can imagine the fear of a pregnant seventeen-year-old who spoke no English and was facing indeterminate detention, deportation, and separation from her siblings.

The family continued to try to raise money for a bond, and the League located a specific family that would employ Anatasia as a live-in domestic worker. Immigration officials rejected the offer. In April, still in detention, Anatasia gave birth to a daughter. Finally, appealing the case to the Secretary of Labor, Anatasia and her daughter were released upon an affidavit that the brother would care for both, and, an informal assurance that the League would continue to monitor the family.[130] Undoubtedly, Edith Abbott’s later publication of documents from the case was intended to demonstrate how immigration officials’ decisions upended a family, created human suffering, while also costing the government money for a long, frightening, and needless detention.[131]

Margaret Hecker, another client of the League, was pregnant when she tried to immigrate to the U.S. with her fiancée Leopold Koenig, who was the father of the unborn child.[132] Ellis Island officials detained Margaret but allowed Leopold to enter the U.S. Upon reaching Chicago, where friends lived, he sought assistance from the League for Margaret. The League advised that he and his male family friend immediately send affidavits of support to the inspector in charge of Ellis Island. Meanwhile, it arranged for the Inspector in Charge of the Chicago immigration office to meet with both men. Failing to obtain entry for Margaret, the League appealed the decision of exclusion to the Secretary of Labor. The appeal explained that Margaret and Leopold could not marry in Germany as Leopold had not completed his military service but assured authorities that they intended to marry as soon as possible. It also represented to the Secretary that Leopold had the finances to support Margaret and their child, and that his friend was also willing to assist the couple. It further reported to the Secretary that the friend lived in a respectable and comfortable home with his wife. The League then firmly chastised the Immigration Bureau for its discriminatory policy of allowing unmarried men who had sired children out of wedlock entry to the U.S. but denying entry to young and “helpless” pregnant women.[133] The League did not hesitate in pointing out the many double standards for men and women that immigration officials applied.

The League then proposed to the inspector that they would care for Margaret before she married and find her domestic work. The Secretary of Labor granted the appeal conditioned upon the couple’s marrying within 30 days of release.

He also required the League to monitor the couple and report back as to whether and when the marriage occurred. League workers attended the wedding and submitted a report. A case such as this was not usual. Here the League played a double role, advocating for Margaret while also monitoring the couple on behalf of the Immigration Bureau.[134] The League saw no conflict of interest.

A similar case involved Maria Boreija, a Lithuanian woman with a young infant, who was detained and denied entry to the U.S by immigration officials at the Canadian border in 1914. Officials had allowed her boyfriend, the father of the child, to enter and immigrate to the U.S. The League represented Maria in front of the Board of Special Inquiry. The Board reversed the decision of the inspector and allowed Maria and her infant to enter the country on the condition that she quickly marry and that the League supervise Maria until the marriage occurred.[135] The League helped the couple obtain a marriage certificate, witnessed the actual marriage, and sent a copy of the certificate to immigration officials, along with a report.[136] Like the League’s role in placing and supervising unmarried women in domestic work as a state-imposed condition of entry, here the requirement that a couple marry could approach the line of forced marriage. It thus called into question the substance of American freedom and liberty. The idea of a consensual marriage was a pillar of the concept of freedom, so much so that immigration officials in other cases refused to recognize arranged marriages as they supposedly lacked the requisite degree of consent.[137] Yet, in these cases, where officials employed double standards for unmarried men and women, marriage or being sent back to one’s native land was the only option that a woman possessed. Consent and coercion seamlessly bled together.

The League also assisted immigrant women whom officials sought to deport on grounds of immorality or for prostitution. In 1907, Congress passed a law which allowed for the deportation of immigrants who entered the United States for “immoral purposes,” and immigration officials at times stretched the clause to apply long after an immigrant had entered and lived in the U.S.[138] Grace Abbott described the ordeal of three young Jewish Russian women who had who had grown up in the United States but been deported for prostitution. She decried that these girls were being sent back to a country where they had no family and would suffer religious persecution. She remarked, “And after these girls had been banished, could anyone feel that the country was safer.”[139] Instead of spending resources on deportation, she proposed that government funds would be better used to ameliorate the conditions of poverty that created the need for women to prostitute themselves. Abbott also pointed out that the men who hired women for sexual services escaped punishment.[140] It was men who created and administered immigration laws, regulations, and practices, and Abbott called for the immigration service to hire women into senior positions (undoubtedly thinking of her coterie of colleagues) who could better understand the predicaments faced by immigrant women.[141]

Some of the League’s more complex cases challenged immigration officials’ understanding of what constituted immoral behavior and even what it meant to be a prostitute.[142] Take the somewhat unruly case of Elena Petrovna. Two months after immigrating from Russia, she was arrested by immigration officials who began deportation proceedings on the grounds of immoral conduct. At Elena’s request, the League represented her. The League’s investigation discovered that Elena’s father in Russia had arranged for her to be married to George Grouble, a Russian immigrant living in Chicago. Grouble gave Elena’s father $140, and paid for Elena’s travel to the U.S. so that they could marry. After arriving in Chicago, Elena refused to wed Grouble, and left him so that she could marry another man, Jan Ivanov, also from her village, and living in Chicago. Grouble reported Elena to immigration officials claiming that she was a prostitute. Quickly, probably on the League’s advice, Ivanov repaid Gouble the $140. Elena and Jan obtained a marriage license, and planned a wedding. Despite this, the Immigration Bureau found Elena to be deportable.[143]

The League argued that the only evidence presented by immigration officials was Grouble’s accusation that Elena was a prostitute and that she lived in a boarding house with a group of unrelated men.[144] Living in such a home was not unusual for immigrant women, and the League included with the appeal a portion of its annual report discussing the prevalence of such living arrangements. The League also claimed that it was well known among Chicago’s Russian immigrant community that Gouble had a poor reputation. If Elena were deported, the League asserted, her reputation in the village from which she came would be destroyed. “The United States government will have condemned a girl against whom there is only a case such as a malicious man could make against almost any Russian or Polish girl in the city.”[145]

Perhaps most importantly, Elena had hurriedly married Jan and the League reported to officials that they were living in a manner that would be “entirely sanctioned by American standards.”[146] The government, not entirely convinced of Elena’s innocence, decided not to pursue the case for the time being but asked the League to continue to monitor the couple. The League’s last report assured officials that they were a happy family, with a good reputation, and that the husband was employed and hardworking.[147] In other words, they were appropriately performing their gendered roles. Whether Elena truly wanted to marry Jan we will never know. Without such a marriage, however, Elena certainly would have been deported. In the eyes of officials (and perhaps the League) marrying Jan transformed Elena’s status from “prostitute” to that of a respectable woman.

The cases discussed above demonstrate how issues of sexual morality, and the very idea of a good or proper home, were crucially important to the League’s understanding of which women were fit to be part of the polis. At times, its leaders’ views mapped on to that of immigration officials. Both, to some extent, believed that immigrant women needed supervision, and saw the League as uniquely capable to undertake such a role. We can also see how the League became an arbiter of what constituted a proper home and behavior for immigrant women.

When requested, the League was also happy to work with the immigration officials, engaging in a process that was part accommodation and part resistance. The League’s close relationship with high level immigration officials before World War I cannot be easily defined nor categorized. The League was only a sometime adversary of the state. It also could readily cooperate, agreeing to investigate immigrants and to even monitor their own clients without any sense of a conflict of interest.[148] In this capacity, the League almost acted as an arm of the administrative state, and drew upon its knowledge of immigrant communities to assist the state. It is tempting to call the League handmaidens to the administrative state. This, however, would be inaccurate, for in other cases the League zealously advocated for clients. Something more delicate and complicated was occurring. In a sense, the League was accumulating cultural capital from its work with immigration officials. Such cultural capital could then be drawn upon to assist other immigrants. The League understood well that it was a repeat player.

The League’s work with immigrant women allowed it to proverbially get its feet wet in interacting with high level immigration officials. Run and managed by a group of women, the League was able to leverage its expertise on European immigrant women to establish itself as a legitimate arbiter and advocate when called in by immigration officials to help in matters involving young immigrant women or representing such women themselves. Although the League was often sympathetic and understanding of the travails faced by immigrant women, and often called out the immigration service for using double and inconsistent standards for men and women, it also participated in an ideology that matched those of immigration officials regarding the control and supervision of such women, and the appropriate performance of gendered respectability.

VI. Becoming A Cultural Broker: World War I and the Draft