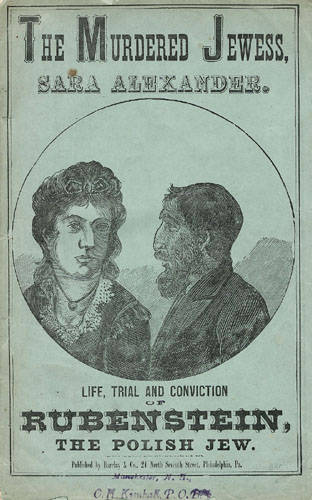

On February 1, 1876 the trial of Pesach Rubenstein for killing Sarah Alexander began. Both Pesach Rubenstein and Sarah Alexander were Yiddish speaking Eastern European Jewish immigrants. The police investigation and following trial showed a system ill equipped to provide justice or a fair trial to people who spoke Yiddish, ate kosher food, testified under affirmation, and celebrated the sabbath on Saturdays. While no explicitly discriminatory laws denied Jewish defendants, or victims, justice in this moment, the lack of access, and the nineteenth century understanding of equal treatment had a decidedly discriminatory impact on Pesach Rubenstein and Sarah Alexander.[1]

While the Rubenstein trial was considered the first murder trial of an Eastern European Jewish immigrant in New York for many years, it is an understudied part of Jewish history because of historiographical assumptions and blind spots ignoring legal discrimination against Jews.[2] Far too long antisemitism in the academy has been reduced to “social discrimination” without a thorough examination of the legal discrimination present in criminal courtrooms and state laws.

Rubenstein’s trial is assumed to be the first of its kind in large part because there has been little historical inquiry into this topic. Five years before Rubenstein’s trial, a Jewish abortion doctor was charged with manslaughter. Alice Bowlsby was found naked in a trunk in a train station on August 26, 1871. It was discovered that she died of a botched abortion, and the doctor, Jacob Rosenzweig, who performed the abortion, was convicted of manslaughter. The pamphlet on this case, “The Great ‘Trunk Mystery’ of New York City,” cast Alice Bowlsby’s death as a great tragedy and Rosenzweig as a demonic Jewish doctor intent on performing abortions without a care for the women he was treating.[3]

Pesach Rubenstein’s trial challenges the historiographical claims that American Jewish immigrants did not face legal discrimination, only social discrimination.[4] Rubenstein and many of the Jewish witnesses in the trial faced implicit legal discrimination as a result of facially neutral laws that did not take Jews into account or ensure access for those outside an assumed White, Christian, able-bodied, English speaking, male citizen.[5] Pesach Rubsenstein suffered from the discriminatory impact of facially neutral laws in such a way as to constitute anti-Jewish bigotry. Jews were subject to the discriminatory impact of criminal procedure that did not ensure a fair trial or guaranteed access to legal personhood rights. While other immigrant groups also faced implicit legal discrimination from an unfamiliar court system, the religious differences layered on racialized ethnic othering, caused unique obstacles for Jewish immigrants attempting to access equal treatment in a courtroom.

It is impossible to understand the treatment of Pesach Rubenstein, or other Jews who came into contact with the criminal justice system, without a systemic legal analysis that considers antisemitism beyond a socially discriminatory realm. In the winter of 1875 police detectives followed procedure to investigate Alexander’s murder, but their ignorance about Jewish customs and language hampered their analysis of evidence and eyewitness accounts. They may not have been intentionally discriminatory, but their actions still resulted in an unjust investigation. For example, police did not know their eyewitness accounts of a man with a beard wearing black clothing likely applied to most Eastern European, religiously observant Jewish immigrant men. Police lineups were not common in the 1870s, and so witnesses would not have been forced to compare Rubinstein’s features with other people dressed in a similar way.

As the police began to gather witnesses, they found multiple men who saw Sarah Alexander and an unidentified man on the ferry to Brooklyn. One witness, Augustus Taylor, described this man as “a thin fellow, very dark featured, had a prominent nose, and wore black straggling sidewhiskers and beard and had a mustache, He wore a slouched hat.”[6]This description employed common racialized stereotypes of Jewish men possessing large noses and dark beards. However, since the Inspector had already seen Pesach Rubenstein, he applied this witness description to Rubenstein.

Perhaps the most significant barrier to gathering evidence in the case was the fact that Pesach Rubenstein spoke Yiddish but Detective Zundt, who spoke German, not Yiddish, acted as an interpreter. Most German speakers would be able to understand some Yiddish but would not be able to converse fluently. The non-Jewish sources written in 1875 and 1876 all describe the language spoken by Rubenstein and his community differently without knowing the people were speaking Yiddish. Some described it as German, Polish, or Hebrew. One described Rubenstein’s “Hebrew acquaintances” as speaking “broken Polish Dutch English.”[7]

During the trial, the defense relied on Jewish alibi witnesses who testified through an interpreter who didn’t speak their language. These witnesses also had issues testifying under oath on a Bible and without their hats on. The court allowed these witnesses to testify under affirmation, instead of under oath, while wearing their hats.[8] Jewish witnesses’ right to testify according to their “peculiar ceremonies” of religion wasn’t protected in New York State until 1857. This right came even later in other states which operated under the assumption that a belief in Jesus was necessary for the oath to guarantee truthful testimony.[9]

While the defense faced religious barriers and cultural bigotry, the prosecution was served by the same obstacles. One of the only Jewish witness for the prosecution, Sarah Alexander’s brother, and the alternate suspect both testified without an interpreter and using the traditional oath to be sworn in.[10] The prosecutor exploited the cultural issues by inflaming the bigotry of the jury in his closing argument. The prosecutor’s closing argument indicted all “Polish Jews” as “peculiar in their characteristics, living in a comparatively small territory; they are dirty, ignorant, uncultivated, have no school education, except what is obtained from their religious teachers, they are oppressed and despised by surrounding races.”[11] The prosecutor not only used Rubenstein’s Jewishness to condemn him but also to question the veracity of all the Jewish witnesses.

On the eleventh day of trial, February 12th, 1876 the jury returned with a verdict after only an hour of deliberation. The presiding judge insisted on sentencing Rubenstein the same day, which happened to be a Saturday afternoon. Two Jewish lawyers, arguing on behalf of Rubenstein’s synagogue, explained that Saturday afternoon was the Sabbath and requested the formal sentencing be postponed.[12] The judge ignored the objection based on religious observance and convened the court for the verdict on Saturday February 12, 1876.[13] Longstanding precedent held that Jews would not receive a “religious exemption” for appearing in court on Saturdays.[14] Rubenstein was convicted and sentenced to be executed on March 24, 1876.

Previous historiography has acknowledged anti-Jewish bigotry in the 1870s but has discussed it in terms of cultural, or social, exclusion and stereotypes without significant violent or legal consequences. This narrative was cemented with John Higham’s writing in the 1950s and his discussion of social anti-Semitism.[15] A recent roundtable on anti-Semitism in the Gilded age and Progressive Era provided an important conversation on the current status of historiographical understandings of systemic antisemitism.[16] Jonathan Sarna referred back to the importance of Higham’s work in understanding anti-Semitism as a social problem and asserts that antisemitism scholarship hasn’t moved past Higham, and Naomi Cohen’s conclusions.[17] Hasia Diner asserted that Jews mostly “functioned as white people” with Jewish women “receiving the respect and protection offered to all white women.”[18] Eric Goldstein challenged these claims by noting that “rhetorical” antisemitism had significant social and institutional consequences. Goldstein noted discrimination in employment, social inclusion, and obtaining credit and loans but stops short of acknowledging legal antisemitism.[19] The reliance on viewing antisemitism through a rhetorical and social lens supports the dominant trend in antisemitism historiography that American Jewishness is “exceptional” in its lack of explicit discrimination. Even Goldstein’s emphasis on institutional consequences of “rhetorical” antisemitism still did not touch on legal discrimination. Historians such as Tony Michaels and David Sorkin push back against the idea that American Jews did not need an “emancipation” moment, a moment of legal emancipation from discrimination. Additionally, legal scholars such as Britt Tevis are beginning to add legal discrimination to the conversation.[20] However the dominant narratives of antisemitism still exclude systemic legal discrimination from the analysis.

Rubenstein faced explicit anti-Jewish bigotry, but he also suffered as a result of ignorance of Jewish customs. There was confusion about his language, his dietary customs, and his religious observance. In the following decades with increased Eastern European Jewish immigration, the courts become more accustomed to Jewish immigrant defendants but that didn’t lessen the anti-Jewish bigotry in the criminal justice system. Such bigotry began to take the form of large-scale stereotypical assumptions and persecutions. Jews were starting to be blamed for, and associated with, particular crimes such as bigamy, white slavery, arson, and pick-pocketing. As more Eastern European Yiddish speaking Jews immigrated to the United States, the societal familiarity with them grew, but they continued to be scapegoated for crimes in service of nativist bigotry.[21] Pesach Rubenstein captured the public’s interest as an extreme example that provided a window into an exotic immigrant community. However, as that immigrant community grew and gained more contact with society and the criminal justice system, the anti-Jewish assumptions about the group’s criminality increased as well. Criminal courtrooms remained sites of implicit legal discrimination through a reliance on anti-Jewish stereotypes and influence from an antisemitic press. The disproportional focus on Jewish immigrants for certain crimes by police and newspapers contributed to cultural exclusion and a denial of full citizenship privileges and immunities into the twentieth century.[22]

One crime particularly associated with Eastern European Jewish immigrants in the early 1900s was white slavery and compulsory prostitution.[23] Moral reformers and the press used the white slavery scare to fuel nativist anti-immigrant fervor, the policing of ethnic boundaries, and the criminalization of interracial relationships. In 1907 lawmakers in New York City responded to the white slavery scare by passing section 2460 of the New York Penal Code to outlaw “compulsory prostitution” (which went into effect in 1910). The language was directed at the pimps or procurers by making a person guilty of a felony if they received money from a woman engaged in prostitution.[24] The law was mostly reserved for cases that involved violence and was commonly referred to as the “white slavery” law in the press and during trials. Even after the passage of this law, most prostitution charges fell on women who were charged with a misdemeanor of “disorderly conduct.”[25]

Between 1910 and 1913 there were only 66 indictments and 18 convictions under the compulsory prostitution law.[26] Anti-white slavery reformer Ernest Bell wrote “It is absolute fact that corrupt Jews are now the backbone of the loathsome traffic in New York and Chicago”[27] in his book Fighting the Traffic in Young Girls. Bell’s assertions were supported by Police Commissioner Theodore Bingham who wrote that “the Jews, while constituting one-fourth the population of Greater New York, supply half its criminals” in an article entitled “Foreign Criminals in New York.”[28]Muckraker George Kibbe Turner wrote an article for McClure’s Magazine, “Daughters of the Poor,”[29] that made so many claims about Jewish white slavery operations a Grand Jury investigation was convened to look into immigrant white slavery traffic.[30] The grand jury found little evidence of a vast Jewish or immigrant white slavery operation, but they instead recommended a commission to study the claims of widespread white slavery in detail. John D. Rockefeller then formed the Bureau of Social Hygiene to conduct further investigation. The first report of this committee entitled “Commercialized Prostitution in New York City” came out in 1913. While the report supported the claims about foreign or immigrant controlled white slavery operations, it did not specify Jewish or any other nationality as the main perpetrators.[31]

In 1913 Abraham Belkin (or Bebkin) was tried twice without a conviction because the defense successfully cast doubt on the innocence of his accuser, Annie Jacobs. The defense argued that Annie Jacobs was with Belkin of her own accord and even implied she had engaged in prostitution before immigrating to the United States. The defense claimed that because both Jacobs and Belkin were Jewish, Jacobs was mostly in contact with Jewish men who would have spoken the same language and could have helped her.[32] The prosecutor argued that Belkin had engaged in the common ruse that mostly Jewish men apparently used to manipulate women into the white slavery trade: promising marriage, sleeping with the women, and then selling them to a house of prostitution, in this case Annie Brown’s house.[33] This argument also invoked common white slavery narratives that the jury would have been familiar with.[34] Additionally, early in the trial, the defense attorney, Sarasohn, accused the assistant district attorney, Edwards, of engaging in antisemitism by comparing a line of questioning to a prosecutor in Russia trying a Jewish man for a ritual blood libel murder.[35]

While “white slavery” prosecutions of Jewish immigrants operated differently than the murder trial of Pesach Rubenstein, white slavery charges were similarly used to allow for the courts and the press to use concern over crime and young women to mask bigotry and anti-immigrant sentiment. The outsized focus on Jewish and immigrant men committing forced prostitution mirrored the racist narratives around the Mann Act and white slavery in general.[36]Muckrakers like Turner wrote exposes of white slavery detailing the vulnerability of poor Jewish girls to prostitution and vice investigations sprung grand juries, but little attention or resources were actually paid to assisting women who found themselves in these situations.

The focus on rhetorical and social antisemitic discrimination has ignored the legal discrimination present in the trials of men like Pesach Rubenstein and Abraham Belkin, but it also has reduced violent acts of antisemitism to outlier examples rather than part of a systemic issue in the United States. The lynching of Leo Frank, a Jewish factory superintendent convicted of murdering 13-year-old Mary Phagan, in 1915 is a thoroughly discussed event in American Jewish history, but there is little consideration of its place in the larger context of antisemitic legal discrimination and extrajudicial violence.

After the Civil War there was an increase in extralegal violence by the newly formed Ku Klux Klan against Black people, carpetbaggers, and those associated with radical republicanism. There were a number of Jewish merchants who employed Black people and opposed Klan actions who faced violence or even lynchings. In 1868, a Jewish dry goods store owner, Samuel Bierfield and his Black clerk, Lawrence Bowman, were lynched in Tennessee. The motive for the murders is unclear but Bierfield’s Republican politics and employment of a Black clerk were likely relevant, it’s possible he was also framed for a white man’s murder.[37] In 1869 a Jewish merchant, Samuel Fleishman, with a record of defending Black people in Florida was murdered by a known Democrat who Fled to Texas after likely killing another Black man.[38]

“Anti-Jewish Violence in the New South” by Patrick Q. Mason[39] details at least four more murders of Jewish men between 1870 and 1895 as well as many instances of mob intimidation against Jewish businesses. However, despite these examples and the discussion of Whitecap violence targeting Jews for working with Black people, Mason still argues that there is little “to suggest a widespread violent antisemitism pervading the rural South.”[40]

Antisemitic violence in the South also continued well into the twentieth century while Jewish immigrants were facing white slavery prosecutions in the North. Leo Frank’s lynching occurred in 1915, and ten years later Joseph Needleman was castrated, but left alive, by a mob for supposedly sexually assaulting a white woman.[41] This pattern of mob violence against Jews in the South must be considered within the larger history of American antisemitism and Klan terror. How can we make claims about the relative effect of legal and violent discrimination while we continue to consider these examples as discreet separate acts of violence?

Pesach Rubenstein’s trial and the white slavery prosecutions illustrates the ways in which the criminal justice system was used to confirm and exacerbate existing bigotries against immigrants and other marginalized and racialized groups in United States history. These discussions of innate criminality served to separate racialized groups from the dominant accepted white protestant citizenry. Additionally, violence against Jewish men in the South following the Civil War was a result of antisemitic nativist bigotry that cast Jewish men as interlopers aligned with Black people over white people. As historians we must consider the legal discrimination and extralegal violence against Jews as part of a systemic problem rather than a long list of exceptions to the exceptional acceptance of Jewish immigrants in the United States.

[1] Nineteenth century interpretations of equal treatment required the law be equally applied, not that the law guarantee equal access.

[2] Moses Richin, The Promised City: New York’s Jews 1870 – 1914. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1962); Eddy Portnoy, Bad Rabbi: And Other Strange but True Stories from the Yiddish Press (Stanford University Press, 2017).

[3] “The great “trunk mystery” of New York city. Murder of the beautiful Miss Alice A. Bowlsby, of Paterson, N.J. Her body placed in a trunk and labellled for Chicago. Many strange incidents made public.” (Philadelphia, Pa.: Barclay & co., 1871). See Appendix for images.

[4] See “Roundtable on Anti-Semitism in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era.” (The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era (2020), 1–33). The roundtable was moderated by David S. Koffman with Hasia Diner, Eric Goldstein, Jonathan Sarna, and Beth Wenger participating.

[5] Facially neutral laws describe laws that do not explicitly discriminate as written but can still have a discriminatory impact in their application.

[6] “Rubenstein: The Murder of the Hebrew Girl.” (The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 16, 1875). “Sidewhiskers” was likely referring to payot.

[7] The Murdered Jewess, Being the Life, Trial and Conviction of Rubenstein, the Polish Jew, for the Murder of the Beautiful Sarah Alexander, His Own Cousin! Startling Evidence! A Shocking Crime! (Barclay & Co., 1876), 23; “Was Rubenstein Guilty of Murder?: America’s First Jewish Murder Trial.” (Jewish Exponent, May 14, 1937).

[8] Philip Matthew Stinson. “Pesach Rubenstein Cheats the Hangman: A Case Study of Punishment and the Death Penalty at Brooklyn’s Raymond Street Jail.” (The Prison Journal, Dec 22, 2009)..

[9] See People v. Samuel Jackson, 3 Parker’s Criminal Reports, 590 (1857) from “Calendar of American Jewish Cases,” pg. 90.

[10] “The Trial of Pesach Rubenstein,” 243-244.

[11] “Trial of Pesach Rubenstein,” 309.

[12] The rulings in “religious exemption cases” allowed for Jews to be sentenced to be forced to testify on their Sabbath. Stansbury v. Marks, 2 U.S. (2 Dall.) 213 (1793); Phillips et al. (Simon’s Executors) v. Gratz, 2 Pen. & W. 412 (1831).

[13] The Murdered Jewess, Being the Life, Trial and Conviction of Rubenstein, the Polish Jew, for the Murder of the Beautiful Sarah Alexander, His Own Cousin! Startling Evidence! A Shocking Crime! (Barclay & Co., 1876), 42-45.

[14] Stansbury v. Marks, 2 U.S. (2 Dall.) 213 (1793); Phillips et al. (Simon’s Executors) v. Gratz, 2 Pen. & W. 412 (1831).

[15] John Higham. “Social Discrimination Against Jews in America, 1830-1930.” (Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society, September, 1957, Vol. 47, No. 1 September, 1957, pp. 1-33).; “Anti-Semitism in the Gilded Age: A Reinterpretation.” (The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 43, No. 4, Mar., 1957, pp. 559-578).

[16] “Roundtable on Anti-Semitism in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era.”

[17] “Antisemitism in the Gilded Age” by Naomi Cohen disagreed with some of Higham’s conclusions by centering the discussion with the Jewish victims and chronicling various examples of anti-Semitism in the last twenty-five years of the nineteenth century. Naomi W. Cohen, “Antisemitism in the Gilded Age.” (Jewish Social Studies, Volume 41, 1979, pp 187-210).

[18] Ibid, pg. 4.

[19] Ibid, pg. 5-6.

[20] David Sorkin. Jewish Emancipation: A History Across Five Centuries (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019); David Sorkin. “Is American Jewry Exceptional? Comparing Jewish Emancipation in Europe and America.” American Jewish History 96, no. 3 (2010): 175-200. Britt Tevis. “‘Jews Not Admitted’: Antisemitism, Civil Rights, and Public Accommodation Laws,” Journal of American History 107, no. 4 (2021).

[21]Gil Ribak, ““The Jew Usually Left Those Crimes to Esau”: The Jewish Responses to Accusations about Jewish Criminality in New York, 1908–1913,” (AJS Review 38, no. 1 2014, pp. 1-28).

[22] Mia Brett, “’Ten Thousand Bigamists In New York’: The Criminalization Of Jewish Immigrants Using White Slavery Panics.” (The Gotham Center for New York History Blog, Oct 27, 2020).

[23] “The Vice Trust: A Reinterpretation of the White Slavery Scare in the United States, 1907 – 1917.” Journal of Social History, Vol. 35, No.1 (Autumn 2001), pg., 5-41.

[24] Penal Law, §2460, subd. 8. Provision enacted by chapter 618 of the Laws of 1910. (The New York Supplement, West Publishing Company, 1914).

[25] Brian Donovan and Tori Barnes-Brus. “Narratives of Sexual Consent and Coercion: Forced Prostitution Trials in Progressive-Era New York City.” (Law & Social Inquiry, Vol. 36, No. 3 Summer 2011, pp. 597-619), 601.

[26] “Annual Report of the Chief Clerk of the District Attorney’s Office, County of New York.” (District Attorney’s Office, New York State, 1914), 57.

[27] Ernest Bell. Fighting the Traffic in Young Girls: or, War on the White Slave Trade.” (Chicago: G. S. Ball, 1910), 188.

[28] “The Jews and General Bingham.” (New York Times, September 16, 1908).

[29] George Kibbe Turner. “Daughters of the Poor: A Plain Story of the Development of New York City As A Leading Center of the White Slavery Trade of the World, Under Tammany Hall.” (McClure’s Magazine Nov, 1909), 45-62.

[30] “General Investigation as to the Existence in the County of New York of an organized traffic in women for immoral purposes,” Jan 10, 1910. Grand Jury. (case# 3317)

[31] “Man’s Commerce In Women: Mr. Rockefeller’s Bureau of Social Hygiene Issues Its First Report.” (McClure’s Magazine 08, 1913), 185.

[32] The People v. Abraham Bebkin. Court of General Sessions of the Peace. City and County of New York, Part IV. October 21, 1913. (Case #1768)

[33] The People v. Abraham Bebkin, pg. 4-29. Annie Brown’s religion isn’t specified in the trial, but she speaks “the Jewish language.” See “Charged With Abduction: Girl Says She Was Kept a Prisoner in Belkin’s Home.” (The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 10, 1913); People v. Annie Brown, 1912 (Case #1651).

[34] Donovan, “Narratives of Sexual Consent and Coercion,” pg. 608.

[35] The People v. Abraham Bebkin, pg. 49. In October, 1913 there was a trial of Mendel Beilis for the murder of Andrew Yushinsky (a young boy) in Kieff, Russia. Beilis was accused of killing Yushinsky in a ritual torture reminiscent of stories of Jews killing Christian children as part of a “blood libel.” The case attracted a lot of attention in New York. See “Monk Accuses Jews: ‘Ritual’ Murder Trial Witness Charges Child Torture” (The Washington Post, Oct 15, 1913). Jewish ritual murder accusations had been used in earlier Russian trials against Jews as well in 1879 and 1902. See “Demolishes Myth Of Ritual Murder: Russian Jewish Lawyer Shows the Baseless Character of the Old Story.” (New York Times, May 19, 1911)..

[36] Brian Donovan and Tori Barnes-Brus. “Narratives of Sexual Consent and Coercion: Forced Prostitution Trials in Progressive-Era New York City.” (Law & Social Inquiry, Vol. 36, No. 3 Summer 2011, pp. 597-619), 601-602.

[37] Testimony Taken by the Joint Select Committee to Inquire into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States. N.p., 1872. (The Making of Modern Law: Trials, 1600–1926), pg. 58; Louis, Kaufman. “Bierfield: Was He Killed Because He Was a Jew?” (Republican Banner (1837-1875); Aug 23, 1868); Paul Berger. “Untold Story of the First Jewish Lynching in America.” (The Forward, Dec 8, 2014).

[38] Testimony Taken by the Joint Select Committee to Inquire into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States. N.p., 1872. (The Making of Modern Law: Trials, 1600–1926), pg. 137.

[39] Patrick Q. Mason. “Anti-Jewish Violence in the New South.” (Southern Jewish History Vol 8, 2005).

[40] “Anti-Jewish Violence in the New South,” pg. 93.

[41] Vann Newkirk. “That Spirit Must be Stamped Out: The Mutilation of Joseph Needleman and North Carolina’s Effort to Prosecute Lynch Mob Participants during the 1920s.” (Southern Jewish History, Vol 13, 2010).