“These contemplative and searching tones constitute the main spirit with which Hartog offers his reflections on Hurst. This same spirit, we hope, informs the way we offer this brief forum on Hartog’s piece. “

-Gautham Rao

[Ed. Note: The following reflections reintroduce Professor Hendrik Hartog’s recently published piece, “Four Fragments on Doing Legal History, or Thinking with and Against Willard Hurst,” Law and History Review 39, no. 4 (Nov., 2021), 835-65, and the critical responses to it that follow in this issue of The Docket.]

Many years ago I found myself seated in a fiery session of the Legal History Colloquium at the New York University School of Law. Professor John Philip Reid had the floor and was displeased. The problem was that the discussion topic of the day was an argument about the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Lochner v. New York (1905). Reid had no problem with the paper itself. Rather, he was annoyed that he had to read yet another analysis of Lochner. To paraphrase Reid’s specific complaint, he wondered why legal historians kept publishing article after article about this single case?[1]

On that fateful day Reid’s fellow seminarians had no answer—at least, no satisfactory answer. But I recalled his frustration when I began hearing from colleagues in the American Society for Legal History that Professor Hendrik “Dirk” Hartog had been working on a piece about J. Willard Hurst.

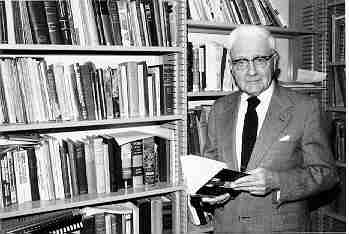

J. Willard Hurst (1910-1997) is the intellectual founder of modern legal history, and especially the modern legal history of the United States. Above all, Hurst urged that legal historians should understand legal doctrine, not as autonomous outcomes of elite legal actors and institutions, but as parts of broader social processes—social, economic, and political. Yet, despite this contextual approach, Hurst also sought to understand law in itself as a creative force that reshaped the social, economic, and political contexts from which it sprang. Hurst’s work was complicated and demanding. Its ambitiousness and vision inspired generations of legal historians in law schools and history departments, first in the United States, and then abroad. The Institute for Legal Studies at the University of Wisconsin Law School stands today as a monument to Hurst’s incredible legacy. The Hurst Summer Institute—a partnership between the Institute for Legal Studies and the American Society for Legal History—is its showcase: a multiweek seminar in which established scholars work with a select group of early career scholars to discuss Hurst’s work and their own. I had the privilege of being a Hurst fellow in 2009 and it was the single most formative scholarly moment of my career.

BUT. Is there really all that much more to be said today about the Hurst opus? The Institute for Legal Studies non-exhaustive list provides citations to 34 articles and book chapters about Hurst’s ideas and methods. Law and History Review has published many of these, beginning with Hartog’s wonderful interview with Hurst, “Snakes in Ireland: A Conversation with Willard Hurst” (1994). Our spring, 2000 (volume 18, issue 4) special issue included the symposium “Engaging Willard Hurst,” featuring articles by Christopher Tomlins, Daniel Ernst, Bryant Garth, Carl Landauer, William Novak, Alfred Konefsky, Robert Gordo, Mary France Berry, Ian Duncanson, W. Wesley Pue, Barbara Welke, Harry Scheiber, and David Sugarman. Welke interviewed Hartog for a wide-ranging discussion of Hurst’s work and legacy in “‘Glimmers of Life’: A Conversation with Hendrik Hartog,” which appeared in our Fall, 2009 (volume 27, issue 3) issue.

There was a second problem in considering another thought piece about Hurst: the frameworks and approaches that legal historians have been using to think about “Hurstian” subjects such as economic growth, while still rooted in Hurst’s insights, have become much more sophisticated and interdisciplinary. The cast of characters at the heart of American legal history in particular now far transcends the “the law makers,” to borrow from the title of Hurst’s 1950 book.[2] As historian Kunal Parker argued in a searching and provocative reassessment of Hurst’s legacy in a 2016 contribution to the American Journal of Legal History, today’s legal historians “have left our origins far behind.” Notes Parker, “ours is a world in which faiths have vanished and overarching orders disintegrated.”[3]

Parker, however, points legal historians away from the temptation to turn the page on our own origin story. He is specifically interested in method. Hartog, while also keyed in on Hurst’s method, also seeks to think through things on a broader register. How do we square today’s profession and field of legal history with a foundational methodology that was almost exclusively focused on a “we,” as Hartog puts it, that consisted only of “white men”? There are “no native peoples, no women, no one who could not participate fully in nineteenth or early twentieth century political society” in Hurst’s works. “For us, living in the twenty-first century, Hurst’s ‘we’ is defined by its absences,” notes Hartog.[4] Hartog thus sets out to take measure, not only of the distance between Hurst’s time and our own, and between Hurst’s method and those prevalent today, but even more importantly, about the moral and ethical stakes of the field’s historiographical cannons and their persisting influence on our practice.

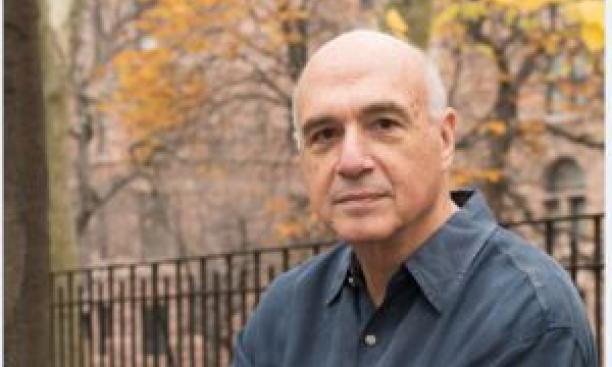

If Hurst is a founder of legal history, then Hartog has been and continues to be one of its driving and sustaining forces. After a lengthy teaching career, first at University of Indiana School of Law and the University of Wisconsin history and law faculties, and then from 1992 until 2020 at Princeton University—where he now holds emeritus status—Hartog was perhaps the single most influential teacher of legal historians in the world. His students can be found on law and history faculties world-wide. Many have clerked for Supreme Court justices. His writings, too, have been formative for several generations of legal historians. His 1985 article “Pigs and Positivism” remains on legal history syllabuses some forty years later. I delight in teaching it to my undergraduate and graduate students alike. His many books, perhaps most notably Man and Wife in America: A History (2009), are equally esteemed.

What is most impressive about Dirk’s “Four Fragments,” however, is the author’s humility. He is seemingly incapable of seeing his own signal importance to the field and profession and instead confronts the promise and peril of his own Hurstianism and gradual, seeming estrangement from it. He tries to tell us how he made sense of his own changing world, even when Hurst’s work grew ever more distant. Maybe at some point down the line it will be time for a proper celebratory festschrift for the career of Dirk Hartog. But right now he is far too impatient for this kind of thing. There is urgent work to be done in the meantime. Legal historians must figure out where we are. And so, he has tried to understand his own story, and to invited us to do the same.

These contemplative and searching tones constitute the main spirit with which Hartog offers his reflections on Hurst. This same spirit, we hope, informs the way we offer this brief forum on Hartog’s piece. Decades from now, legal historians will look back at Dirk Hartog’s work and try to make sense of how he shaped the field so powerfully, for so long. Perhaps one day, after seeing dozens upon dozens of articles about Hartog’s work and importance, a journal editor like me will wonder whether they should forge ahead with yet another exploration of the thought of Hendrik Hartog. They’d be lucky to get anything like the article I received from Hartog about Hurst. For legal history’s sake, I hope they do.

The two pieces we offer as part of this forum come from authors who represent different parts of Hartog’s career. The first, by Professor Mark V. Tushnet, charts the trajectory of a career that parallels Hartog’s, and similarly thinks through the limits and possibilities of Hurst’s work. The second, by Professor Risa Goluboff, seeks to shed further light on the connections between Hurst and Hartog’s work. Goluboff, who studied under Hartog, sees his influence as far outstripping that of Hurst. “In other words,” she concludes, “it is Dirk who has enabled me (and my generation and beyond?) to visualize the relationship between legal history, history, and law…” Our story, she writes, “has nothing to do with Hurst. And everything to do with Hartog.”

[1] Lochner v. New York, 198 US 45 (1905). On Reid’s scholarly contributions, see Hendrik Hartog and William E. Nelson, ed, Law as Culture & Culture as Law: Essays in Honor of John Phillip Reid (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000).

[2] James Willard Hurst, The Growth of American Law: The Law Makers (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1950).

[3] Kunal Parker, “Writing Legal History Then and Now: A Brief Reflection,” American Journal of Legal History 56, no. 1 (March, 2016), 176.

[4] Hendrik Hartog, “Four Fragments on Doing Legal History, or Thinking with and against Willard Hurst,” Law and History Review 39, no. 4 (Nov., 2021), 847-8.