Editor’s Note: Bruce W. Dearstyne’s latest book, The Crucible of Public Policy: New York Courts in the Progressive Era (SUNY Press, 2022), will be published in early 2022. Below, he discusses some of the key ideas in the book.

New York’s Court of Appeals and Progressive Reform: Judicial Statesmanship in Action

New York State’s highest court, the Court of Appeals, merits more attention from historians. Over the years, it arguably has been one of the nation’s most important state courts.

The Court of Appeals’ leadership is demonstrated by its approach to key cases in the Progressive Era, ca.1890-1920.[1]

New York in those years pioneered in legislation to regulate business practices, workplace hours and safety, public health, and other social and economic areas. These reforms were often challenged in court on the grounds that they made government too intrusive or contravened constitutionally guaranteed liberties of individuals or corporations.

The Court of Appeals became, in effect, the forum of last resort where complex social and economic issues were debated and resolved. Appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court were uncommon at that time.

Six themes emerge from a study of the court in that period. They are worth attention because many of the issues are similar to what courts are still considering today.

Rely Selectively on Precedence

The court was respectful of, but not overly deferential to, the concept of stare decisis or being guided by previous judicial decisions. The court’s opinions are replete with references to the its own previous rulings as well as decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court which provided guidance for state courts as well as federal courts. In some cases, the Court of Appeals referred to decisions by other states’ courts and occasionally to English courts (a source of guidance on some issues at that time).

In the closing years of the 19th century, “the worship of precedent, the recognition of stare decisis as an absolute dogma, went on with scarcely a voice of dissent or protest. The decision may have been wrong but we were never to doubt it. It might be beside the point. Still, we would cite it, especially if it were well known,” recalled Cuthbert W. Pound, Associate Judge on the Court of Appeals 1915-32 and Chief Judge, 1932-34.[2]

But in the early 20th century, the state’s high court shifted to a more flexible stance. Precedence still counted but the law had to evolve. “Case law, in a qualified way at least, is a progressive science,” judge Pound explained. “A decision does not, merely because it is old, fetter the courts forever.”[3] The court decided it needed to “cast off the iron bands of precedent as a senseless impediment to free action and to make a fresh start.” Judges acknowledged that “law based on a traditionary line of decisions has become an impracticable and antiquated method of doing justice.”[4] Courts needed to interpret laws more in the light of contemporary circumstances and needs.

“The Court of Appeals in the progressive era took a pragmatic, judicious approach. It balanced respect for legislative authority against the need alignment with the federal and state constitutions. Usually the court approved new government policies and programs, sometimes expressing caveats and caution at the same time. Sometimes, it set limits or invalidated laws which the legislature later re-enacted with changes to meet the court’s objections. In a few cases, new laws or an amendment to the state constitution were needed.“

-Bruce W. Dearstyne on New York’s Progressive Era Court of Appeals

Avoid Making Decisions that Constitute “judge made law”

Stare decisis was closely related to the concept of the “common law,” the body of unwritten law based on judicial decisions and legal precedents established by the courts. That was sometimes called “case law” (in contrast to statutory law) or “judge made law.” In applying what it perceived as a longstanding common law principle, a court might validate or strike down a statute.

But the Court of Appeals rarely used its power to create its own bit of common law by stretching existing rulings or giving its own expansive interpretations to constitutional provisions.

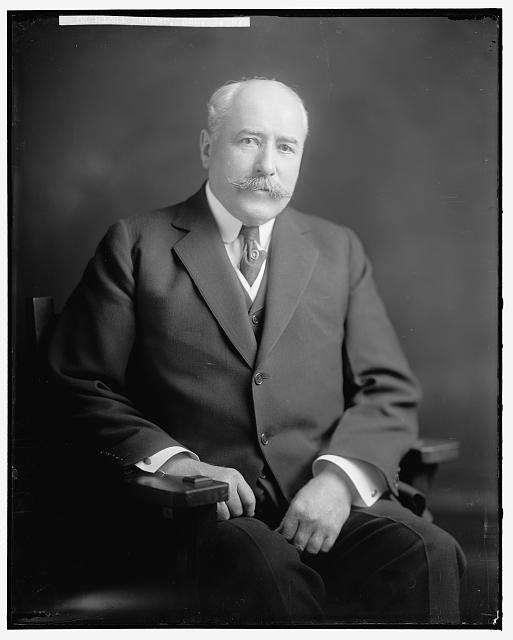

For instance, in a 1902 case a woman claimed that unauthorized commercial use of her photo in ads for flour constituted a violation of her privacy. That right was not defined in the federal or state constitutions or in state law, and while previous Court of Appeals decisions had implied the courts had the constitutional right to bestow it, and some legal scholars had endorsed that view, no court had done so. Chief Judge Alton Parker (1898-1904) denied her claim. The “so-called right of privacy” was vague. The ads might be “distasteful to her” and “damage her feelings, but they were not illegal. The right of privacy “has not yet found an abiding place in our jurisprudence,” he wrote. That would require legislation.[5]

The Chief Judge was exhibiting judicial modesty. The next year, taking Parker’s advice, the legislature passed the state’s first personal privacy law and the court later approved it.

Defer to the Legislature Whenever Possible

The Court of Appeals proceeded on the working assumption that it should validate state laws unless they were clearly defective or blatantly violated the state or national constitutions. That principle distinguished New York’s high court from its counterparts in many other states and from the U.S. Supreme Court in this time period. Those courts were more conservative and more inclined to question legislatures’ wisdom and understanding of the impact of the regulatory laws they were passing.

Chief Judge Parker, in a 1900 opinion approving a statute regulating railroads, summarized the notion of deferring to the legislature: “Whether the legislation was wise is not for us to consider. The motives actuating and the inducements held out to the legislature are not the subject of inquiry by the courts, which are bound to assume that the law-making body acted with a desire to promote the public good. Its enactments must stand, provided always that they do not contravene the Constitution…But in applying the test the courts must bear in mind that it is their duty to give the force of law to an act of the legislature whenever it can be fairly so construed and applied as to avoid conflict with the Constitution.” [6]

Address the issue of Liberty and the 14th Amendment

The Court of Appeals, in company with other state courts and the U.S. Supreme Court, spent a good deal of time interpreting and applying the 14th Amendment’s phrase “nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” That amendment, adopted in 1868, was intended to protect the rights of newly liberated Black Americans in the south. Corporate attorneys later reinterpreted it to cover the rights of individuals and corporations to be free of government interference. The state constitution had similar wording but it was the 14th Amendment that got the most attention.

Several state courts and the Supreme Court used the “due process” clause to strike down one piece of regulatory legislation after another in the progressive era. New York’s Court of Appeals is harder to categorize. In the early years of the progressive period, it was more inclined to use “due process” to invalidate laws, but less inclined to do so as time went on. But the court’s path was inconsistent and it often split, 4-3, on key decisions.

For instance, in 1896 a barber appealed a conviction and fine for violating a law forbidding barber work on Sundays. A deprivation of his liberty, he said, to work when he pleased. The court upheld the law, 4-3. The law might infringe on individual barbers’ rights, but it was within the state’s power. The “sanction for these apparent trespasses upon private rights is found in the principle that every man’s liberty and property is, to some extent, subject to the general welfare as each person’s interest is presumed to be promoted by that which promotes the interest of all.”[7]

In 1904, the court upheld an 1895 law restricting the working hours of bakery employees and imposing sanitary regulations. A baker charged that the law deprived him of liberty and property without due process. The Court of Appeals upheld the law, but in another 4-3 decision. Chief Judge Parker had already asserted that the 14th amendment was intended to protect recently liberated Black Americans and should not be applied to shield businesses from state oversight.[8] In the court’s majority opinion, he held that the law was valid because the state had the power to regulate for the public good.[9]

But the next year, the Supreme Court overruled the New York court in what became a famous decision in Lochner v. New York. The 14th Amendment was cited as a deterrent to restrictions for people to contract to work and earn their livelihood as they pleased. The Supreme Court’s Lochner decision was often cited thereafter by attorneys using the 14th Amendment to bludgeon regulations.[10]

The Court of Appeals for the most part followed the Supreme Court’s Lochner guidance but not always. In 1907, the court invalidated a law regulating the sale of real estate as an unwarranted infringement on individual rights and liberties. “The legislature may not, under the guise of protecting the public interest, arbitrarily interfere with private business or impose unusual and unnecessary restrictions upon lawful occupations…. Liberty, in its broad sense, means the right not only of freedom from servitude, imprisonment or restraint, but [also] the right of one to use his faculties in all lawful ways; to live and work where he will, to earn his livelihood in any lawful calling and to pursue any lawful trade or avocation.” [11]

On the other hand, the Court of Appeals was usually more inclined to recycle and apply Parker’s expansive view rather than Peckham’s restrictive one. A 1905 decision approved a law to require real estate agents operating in first and second-class cities (New York City and the state’s other large cities) to be registered and licensed by city authorities. An unlicensed agent in New York City said that violated his 14th amendment rights without due process of law. The high court disagreed. “If the statute comes fairly within the scope of the police power it is a valid law, although it may interfere, in some respects, with the liberty of the citizen, which of course includes his right to follow any lawful employment. A statute to promote the public health, the public safety or to secure public order or for the prevention or suppression of fraud is a valid law, although it may, in some respects, interfere with individual freedom…. Individual freedom must yield to regulations for the public good…. Legislation is valid which has for its object the promotion of the public health, safety, morals, convenience and general welfare or the prevention of fraud or immorality.” [12]

Sanction the Administrative State

New York progressive reformers began to introduce new regulatory agencies that were examples of the emerging concept of what would later be called the “administrative state” – powerful administrative agencies with the authority to promulgate rules with the force and effect of law, enforce regulatory compliance, and make binding decisions about public rights and services. A 1905 law created the State Commission of Gas and Electricity with extensive powers to regulate the price of gas and electricity, inspect facilities, prescribe bookkeeping requirements, and regulate the issuance of stock. A Saratoga company appealed a commission ruling, asserting that only the legislature could exercise such sweeping powers.

The Court of Appeals upheld the law in a 1908 decision. By then, the case was somewhat moot because the Gas and Electricity Commission had been superseded by even more powerful Public Service Commissions. But the court’s decision was so broad that it applied to the PSC and was a precedent for other, similar agencies in the future.

Chief Judge Edgar Cullen wrote that the legislature could delegate rate-setting authority to a commission. In fact, that was essential in modern times where the legislature lacked the time and expertise to oversee every public utility in the state. “What is entrusted to the commission is the duty of investigating the facts, and, after a public hearing, ascertaining and determining what is a reasonable maximum rate.” The commission had the expertise and objectivity to determine what is reasonable after considering evidence from companies and consumers.

Indeed, “a lawmaker might exhaust reflection and ingenuity in the attempt to state all the elements which affect the reasonableness of a rate,” only to find that he had overlooked or ignored something. The commission, and other agencies like it, were within the legislature’s constitutional power to delegate broad authority.[13]

Reverse Course When Presented with Compelling New Evidence

The Court of Appeals sometimes admittedly changed its collective mind when presented with new evidence.

In 1905, in a case involving a law regulating the bulk sale of goods, the court held that the legislature has “overstepped the limits of its power” with this “drastic and cumbersome” law. The “shibboleth of legislatures and courts known as the police power . . . begins where the Constitution ends” and can’t be used to trample on constitutionally guaranteed rights.[14] But as in many cases in the progressive era, the court was divided, 4-3. The dissenters argued that this law promotes the public welfare and should stand.

In 1916, considering a law passed in 1912 that was much like the one struck down in 1905, the court reversed itself. In the intervening years, more states had passed similar legislation and state courts and the U.S. Supreme Court had become more tolerant. Said the court: “We think it is our duty to hold that the decision in Wright v. Hart [the 1905 case] is wrong…..At the time of our decision in Wright v. Hart, such laws were new and strange. They were thought in the prevailing opinion to represent the fitful prejudices of the hour. . . . The fact is that they have come to stay, and like laws may be found on the statute books of every state. . . . In such circumstances we can no longer say, whatever past views may have been, that the prohibitions of this statute are arbitrary and purposeless restrictions upon liberty of contract. . . . The needs of successive generations may make restrictions imperative to-day which were vain and capricious to the vision of times past. . . . Our past decision ought not to stand.” [15]

In 1907, the court struck down a law banning night work by women in factories. The law was meant to protect women but it was an unconstitutional interference with their right to work and employers’ right to hire them, said the court. A woman worker is not “a ward of the state” meriting special protection.[16]

Advocates got the legislature to enact a similar law in 1913, adding the rationale that its purpose was “to protect the health and morals of females employed in factories.” The law’s constitutionality was challenged two years later. This time, advocates presented evidence from a study of women in the bookbinding trade (the company challenging the law was a publisher), a state investigating commission report showing the baneful effects of night work by women and a brief with extensive documentation on women’s factory working conditions prepared mostly by Louis Brandeis, an activist attorney (and later a Supreme Court justice).

The court reviewed the documentation, declaring that the legislature clearly had enough evidence about the need for the law. It was in “the interest of public health and welfare” and constitutional law.[17]

The Court of Appeals in the progressive era took a pragmatic, judicious approach. It balanced respect for legislative authority against the need alignment with the federal and state constitutions. Usually the court approved new government policies and programs, sometimes expressing caveats and caution at the same time. Sometimes, it set limits or invalidated laws which the legislature later re-enacted with changes to meet the court’s objections. In a few cases, new laws or an amendment to the state constitution were needed.

Overall, the court exhibited a high degree of judicial statesmanship and effectiveness.

[1] This article draws on my forthcoming book The Crucible of Public Policy: New York Courts in the Progressive Era (Albany: SUNY Press, 2022). The Historical Society of the New York Courts provides histories of the New York courts, biographies of the judges, and other information online. Other sources include Francis Bergan, The History of the New York Court of Appeals (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985); Lawrence M. Friedman, A History of American Law (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019); and G. Edward White, Law in American History, Volume II: From Reconstruction Through the 1920’s (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

[2] Cuthbert W. Pound, “Jurisprudence: Science or Superstition,” American Bar Association Journal 18 (1922), 312.

[3] Cuthbert W. Pound, “Some Recent Phrases of the Evolution of Case Law,” Yale Law Journal 31 (1921-1922), 365, 366.

[4] Pound, “Science or Superstition,” 312.

[5] Roberson v. Rochester Folding Box Company, 171 NY 538, 543, 556 (1902).

[6] Bohmer v. Hoffen, 161 NY 390, 399–400 (1900).

[7] People v. Havnor, 149 NY 195, 199, 206 (1896).

[8] Alton B. Parker, “Due Process of Law,” The American Lawyer 11 (1903), Part I, 333-336; Part II, 388-391; Part III, 431-434.

[9] People of the State of New York v. Joseph Lochner, 175 NY 145 (1904); Bruce W. Dearstyne, “The Lochner Case: New Yorkers in Conflict,” New York State Bar Association Journal 89 (February 2017), 26-31.

[10] Lochner v. New York, 189 U.S. 195 (1905).

[11] Fisher Co. v. Woods, 187 NY 90, 94, 95 (1907).

[12] People ex rel Armstrong v Warden of City Prison, 183 NY 223, 226 (1905).

[13] Village of Saratoga Springs v. Saratoga Gas, Electric, and Power Company, 191 NY 123, 143, 147 (1908).

[14] Wright v. Hart,182 N.Y. 330, 335, 341 (1905).

[15] Klein v. Maravelas, 219 N.Y. 383, 385–387 (1916).

[16] People v. Williams, 189 NY 131, 136 (1907).

[17] People v. Charles Schweinler Press, 214 NY 395, 409 (1915).