Ed. Note: The Docket recently asked Carter Findley to give our readers a brief overview of his new book on the life and work of one of the most important but neglected legal thinkers, diplomats, and men of letters of the Enlightenment: Mouradega d’Ohsson.

Carter Vaughn Findley, Enlightening Europe on Islam and the Ottomans: Mouradgea d’Ohsson and His Masterpiece, Brill, Leiden, 2019, xv + 398 pages.

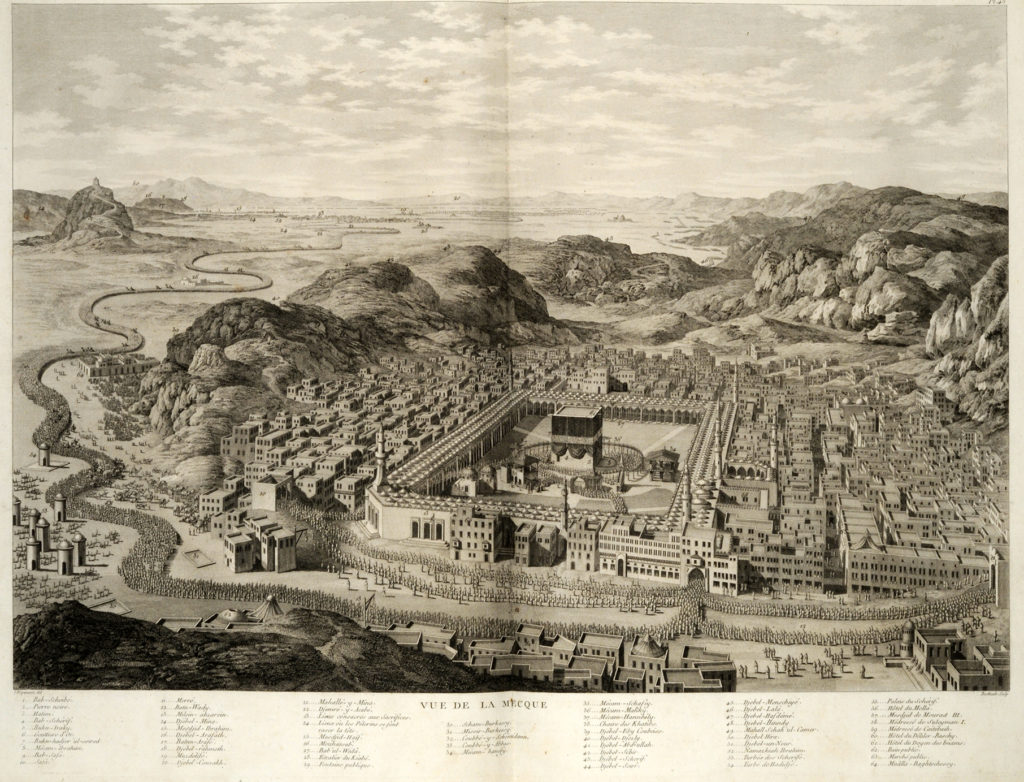

What did the enlightened despot of the eighteenth century need to know about Islamic law and the state to get along with the greatest Muslim ruler of the age? If Mouradgea d’Ohsson could have published his entire work before the French Revolution, his Tableau général de l’Empire othoman would have been recognized then and since as providing precisely that guidance. As its long subtitle states, his work has two parts: the larger part on Islamic law, the final part on the state. This was the most authoritative work ever yet published on Islam and the Ottomans. Profusely illustrated with 233 engravings, the work also offered the century’s richest collection of visual imagery on the Ottomans and opened deep insights into the processes and politics of illustrated book production in this period. D’Ohsson wrote for powerful and prestigious readers. The demand for this work sprang from an episode unique in the annals of European states’ relations with the Ottomans: a reigning European monarch, Sweden’s Charles XII’s five-year residence with a large entourage at Bender in Ottoman Bessarabia (1709-1714). Demands for a Linnean taxonomy of practical information about Islam and the Ottomans began then. No one could complete the full array until d’Ohsson, the brilliant secretary-interpreter of the Swedish mission in Istanbul, did seventy-five years later. So high were his princely patrons’ expectations that the entire Tableau was published simultaneously in two different editions: 3 fully illustrated folios (Paris, 1787-1820) for rich collectors and 7 partially illustrated small volumes (Paris, 1787-1824) for the wider public.

My book contributes to comparative legal history in two respects. One of the greatest obstacles to analyzing d’Ohsson’s work, addressed in chapter six, is to understand his intentions in presenting Islamic law as a “code” that encompassed the “universality of religious legislation.” In our day, no serious Islamicist thinks that sharia law can be codified. In his day, legal codification was an aspiration, but no major European state yet had a codified legal system that applied throughout the land. What was d’Ohsson trying to accomplish in asserting that the Ottomans had achieved a level of legal systematization that Europeans had not? Empirical answers to this question emerge from contexts as far apart as those of Swedish jurists, Ottoman medreses and consular courts, Armenian merchants at Astrakhan, and Jewish legal scholars in Ottoman Safed. Conceptual answers to this question emerge from perceiving that d’Ohsson did not distinguish codification from canonization of what the Ottomans knew as “books of high repute.”[1]

D’Ohsson financed his lavish illustration program by spending a fortune that he had made in Istanbul in trade, both on his own account and as homme d’affaires for the Swedish envoys whom he served officially. D’Ohsson’s business dealings, both in Istanbul and with the leading Parisian engravers, seldom failed to generate acrimonious disputes, typically settled by arbitration. Voluminous documentation survives about these disputes, including one that was pursued all the way to royal arbitration in Stockholm. As a result, the sources for this study offer extensive insights into the reliance on arbitration in the lex mercatoria in this period.[2]

[1] Index entries for “codes” and “codification” on page 394 identify relevant passages.

[2] Index entries under “arbitration” identify relevant passages.