In August, 2020, The Docket had the pleasure of speaking with Dr. Julia Rose Kraut about her new book, Threat of Dissent: A History of Ideological Exclusion and Deportation in the United States, which was published by Harvard University Press (2020).

The Docket [TD]: For those who are unfamiliar, could you please describe what you mean by “ideological exclusion and deportation in the United States” and share a bit about its history? Do you see connections between this history and current restrictions, or those over the last few years?

Julia Rose Kraut [JRK]: Ideological exclusions and deportations bar or expel foreign noncitizens from the United States based on their political beliefs, expressions, and associations. Since the Alien Friends Act of 1798, Congress has passed or revised ideological exclusion and deportation laws in the name of national security after an act of violence, during wartime or an economic depression, or at a time of national/international upheaval. I argue that ideological exclusions and deportations are tools of political repression used to suppress the threat of dissent including criticism of the United States and its politicians and policies, calls for revolution, or associations with anarchists, Communists, or terrorist organizations.

Ideological exclusions and deportations have endured because the majority of the Supreme Court has interpreted them as an immigration issue and not as a First Amendment issue – applying an immigration legal doctrine called the “plenary power doctrine,” which requires judicial deference to the legislative and executive branches of government to pass and enforce exclusion and deportation laws. This doctrine also insulates these laws from substantive judicial review and strict scrutiny under First Amendment legal standards. Over the course of the 20th century, First Amendment jurisprudence has provided more speech protective legal standards for free expression and association, but ideological restrictions have not been evaluated under these more speech protective standards, which enables them to continue to be used as tools of political repression.

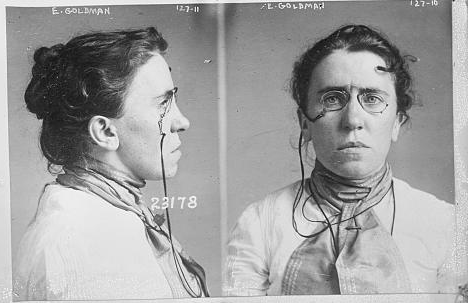

Threat of Dissent examines the underlying dynamics and motivations behind the passage and enforcement of ideological exclusion and deportation laws (including tensions within presidential administrations and between public officials) and describes the legal and non-legal actors who implemented or challenged these laws, as well as those deported or excluded under them. This history includes familiar figures like Clarence Darrow, Emma Goldman, John Lennon, Graham Greene, Charlie Chaplin, Carlos Fuentes, Gabriel García Márquez, Frances Perkins, and J. Edgar Hoover, as well as less familiar figures like Louis F. Post, Ernest Mandel, Senator Patrick McCarran, Carol Weiss King, and Leonard Boudin.

This book is a chronological narrative that begins with the passage of the Alien Friends Act of 1798 and ends in the Trump administration. I discuss President Trump’s extreme vetting policies, including the Travel Ban, often referred to as the “Muslim Ban,” which the Supreme Court upheld under the plenary power doctrine and legal precedent described in the book. I also examine the Trump administration’s use of selective deportation to expel critics and activists and its use of foreign noncitizens’ social media accounts to ideologically exclude. While the technology has changed, the government’s use of ideological exclusions and deportations as tools of political repression has remained the same.

TD: This is a book that is incredibly rich, incorporating a variety of primary sources! Can you walk our readers through how you went about conducting archival research for the project? Are there any moments in the research process that stand out as particularly memorable?

JRK: Threat of Dissent is a legal, political, and social history of ideological exclusion and deportation in the United States, and, in order to write this history, I had to analyze federal statutes and court decisions, appellate arguments and briefs, official and personal correspondence, and government documents and records held in archival collections and obtained under the Freedom of Information Act. I could not have written this book without the guidance from archivists and librarians at the National Archives and Library of Congress, as well as the Massachusetts Historical Society, New-York Historical Society, Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Columbia University, Tamiment Library at New York University, and Joseph A. Labadie Collection at the University of Michigan.

There were so many exciting moments while conducting archival research for this book, but there were two that are particularly memorable. I vividly recall when Peter Drummey, the Stephen T. Riley Librarian at the Massachusetts Historical Society, showed me an original copy of a blank warrant for deportation under the Alien Friends Act of 1798, signed by President John Adams. While Adams ultimately did not deport anyone, the Alien Friends Act was the first ideological deportation law and is essential to understanding the history of ideological exclusion and deportation in the United States. I knew immediately when I saw that document that I wanted to include it in my book. Thanks to the Massachusetts Historical Society, an image of Adams’ signed blank warrant appears in Chapter 1.

The other memorable moment occurred when I was conducting archival research at the Library of Congress and found a letter from Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall to Chief Justice Warren Burger explaining how Marshall had changed his mind and could no longer join or write the majority opinion in Kleindienst v. Mandel (1972). After finding this document, I realized that Threat of Dissent would not only be able to provide the story behind the Nixon administration’s exclusion of Belgian Marxist economist Ernest Mandel, but also behind the Supreme Court’s decision to uphold Mandel’s exclusion, including why Marshall wrote a dissenting opinion and why Justice Harry Blackmun wrote the majority opinion.

TD: Fear—and the state’s project of instilling fear—seems to lie at the heart of your book. Can you explain the “chilling effect” and how this is less a story about mass deportations and more about suppressing dissent from abroad—and at home?

JRK: As I argue in the book, the story of ideological exclusion and deportation in the United States is not a story of numbers but one of fear. The fear of subversion and the threat of dissent, and the fear of being excluded or deported based on one’s beliefs, expressions, and associations. Only a small fraction were ideologically excluded or deported, but the numbers recorded do not take into account voluntary departures of foreign noncitizens or those who chose not to come to the United States, fearing exclusion and the humiliation of being questioned about their beliefs and affiliations by government officials. The numbers also do not capture the “chilling effect,” the fear and intimidation resulting in self-censorship, including inhibiting expression, concealing belief, and precluding free association. Furthermore, as tools of political repression, ideological restrictions not only suppressed foreign noncitizens, exploiting their vulnerability to exclusion or deportation, but also prevented and suppressed free expression and association of American citizens in the United States. These citizens argued that exclusion and deportation, as well as the chilling effect caused by the threat of exclusion and deportation of foreign noncitizens, was a form of censorship, which violated their First Amendment right to receive information and to hear.

TD: How much does the history of ideological exclusion and deportation in the United States have to do with national identity and demarcating who or what is “un-American”?

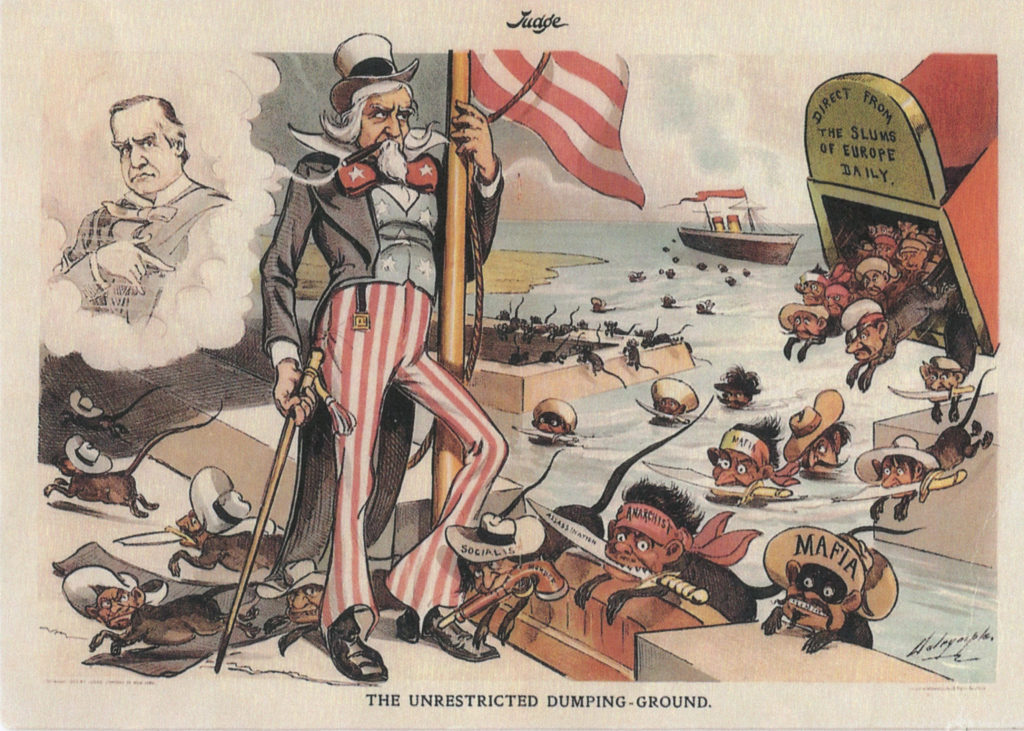

JRK: Proponents of ideological exclusion and deportation laws argued that such restrictions were necessary to establish and maintain America’s national identity as well as to preserve and protect democracy from the threat of dissent. For instance, during the Cold War, they viewed barring or expelling Communists as reflecting the nation’s anti-Communist identity, and as a tool to prevent the spread of Communism and its perceived threat to democracy at home and abroad. They also deemed expressions of dissent as “un-American” in order to justify restriction and repression, as well as to support ideological exclusion and deportation of foreign noncitizens, who they depicted as the source of subversion and scapegoated as the importers and spreaders of radicalism and labor agitation within the United States. Critics of ideological exclusion and deportation laws argued that these laws ran contrary to American liberal, democratic values, and prevented free expression and exchange, which are essential to self-government. Such restrictions depicted the United States as fearful, insecure, and repressive, undermining its reputation abroad and its identity as a “nation of immigrants.”

TD: Now that your book has been published, what’s next? Our readers would love to hear about projects you are working on.

JRK: At the moment, I am busy promoting Threat of Dissent, participating in virtual book talks and discussions, and working with law and history professors who are teaching the book or including ideological exclusion and deportation in their Fall semester courses. Also, I have recently completed and started a few new projects involving more writing on immigration, as well as national security and First Amendment law and history. I was one of the contributors to Whistleblowing Nation: The History of National Security Disclosures and the Cult of State Secrecy (Columbia University Press, 2020), edited by Kaeten Mistry and Hannah Gurman, which was published in March. It is a collection of fascinating essays discussing the importance of whistleblowers’ revelations of government misconduct and illegality, as well as providing a fresh perspective on the history of whistleblowing in the United States. My essay addresses the lawyers who defend whistleblowers. I focus on Leonard Boudin and his representation of Daniel Ellsberg, who faced criminal prosecution under the Espionage Act for his disclosure of the Pentagon Papers in 1971. In this essay, I describe how Boudin’s prior cases, experience, and expertise influenced his legal strategy during the Ellsberg trial and led to his success in obtaining a dismissal of the charges and a mistrial. I also discuss how the Nixon administration targeted Boudin and attempted to use his background, associations, and controversial clients to discredit Ellsberg and to try to secure his conviction. A renowned First Amendment lawyer, Boudin not only defended Ellsberg, but he also challenged the use of ideological exclusion by the Nixon administration, which I examine in Threat of Dissent.