Every year, the American Society for Legal History awards the Kathryn T. Preyer Scholars Prize to one or more scholars “at the beginning of their careers” to acknowledge significant, original research “on any topic in legal, institutional and/or constitutional history.” The prize includes an honorarium to reimburse costs of attending the annual ASLH annual meeting. One of the winners of the Kathryn T. Preyer Prize for 2020 is Smita Ghosh. The Docket is pleased to have had the opportunity to learn a bit more about her work!

Smita Ghosh: The ACPFB’s Fight Against Immigration Enforcement

While researching the history of immigrant detention in the United States, I came across a fascinating organization called the American Committee for the Protection of the Foreign Born (ACPFB). A journal article by ACPFB lawyers alerted me to immigration authorities’ use of detention in the 1940s and ’50s.[1] We commonly think of immigrant detention as a phenomenon of the 1980s and ’90s—the mass incarceration era—so the Cold War use of detention, as well as an alternative to detention called supervisory parole, surprised me.

I was also drawn to the lawsuits generated by Cold War immigration enforcement. The ACPFB was not primarily a legal organization, although it included a great many lawyers. They organized press campaigns, protests (some, as Rachel Ida Buff has noted, involved tri-cornered hats), and a surprising number of folk dances.[2] They hectored Ernest Hemmingway into writing press releases. (If you can’t tell, I ate up their pamphlets and other ephemera, which have a certain flair that their legal briefs might lack). The ACPFB also filed lawsuits, though, demonstrating that the INS’s Cold War immigration powers were more vulnerable than the major Supreme Court cases of the era would suggest. But there was a limit to the ACPFB’s success. The organization was more successful in limiting the detention and supervision immigrants within the country—many of whom were “undeportable,” because their countries of birth refused to grant their travel documents—and less successful in challenging the deportation of migrants from cooperative countries, including the expulsion of thousands of migrant workers in the “Operation Wetback” drives of the early 1950s.

The records of ACPFB lawyers illustrate how government officials used immigration laws to seek political and ideological conformity from non-citizens during the Cold War. The immigration provisions of the McCarran Internal Security Act (1950), a piece of Cold War legislation that has received little attention from immigration scholars, allowed immigration officials to detain non-citizens during their deportation proceedings and for six months afterwards.[3] As soon as the Act went into effect, branch offices of the INS received telegrams from Washington that instructed them to “[a]pprehend and detain immediately all active communists.”[4] INS officials arrested current and former Communist Party members, labor organizers, and non-citizens who worked for the leftist press, many of whom had lived in the United States for years.

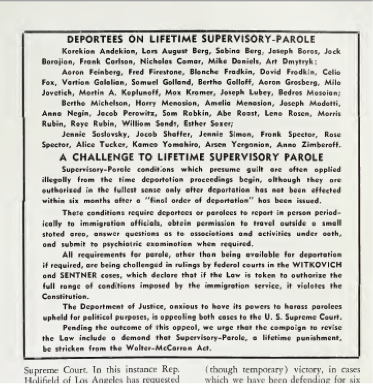

The INS also used its supervision power—another enforcement device created by the Internal Security Act—to control radical non-citizens. The Internal Security Act only allowed the government to detain a non-citizen for six months after he or she was ordered deported. Many of the individuals who the INS supervised had been formally deported but remained in America because other countries would not accept their return. Federal officials often had difficulty convincing other countries to “take back” their citizens because the country in question objected to some aspect of the deportee. This was especially true of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe and of those who were deported for committing crimes or falling into a “subversive” category. Sometimes, the refusal to accept deportees symbolized a diplomatic breakdown between American authorities and the country itself; for years, INS reported that the Soviet Union invoked technicalities to refuse deportees, and that Poland and Czechoslovakia never responded at all. In other cases, it was hard to find a country of deportation at all, because the immigrant’s nationality was unclear.

Without the ability to detain, the INS imposed supervision orders that profoundly impacted immigrant lives. Many orders of supervision required non-citizens to “disassociate” from Communist Party members or “affiliates.” Taken literally, this type of restriction could have drastic consequences. Nat Yanish, a self-proclaimed “proud” Communist, would have to give up his job at the Daily People’s World. David and Blanch Fradkin, former Communist Party members who had been married for decades, would have to get divorced. The supervision cases made clear that the INS’s efforts at social control by immigration law would go as far as the immigrant bedroom.

In other words, the six-month limit to the government’s detention power—a provision that was hard-won by Congressional liberals in 1950—led to more pernicious forms of government control. ACPFB members sometimes alleged that supervision helped the government more than detention or deportation would, because INS officials could use orders of supervision to investigate potential Communist Party members. When they supervised George Witkovitch, who worked for a Slovenian newspaper Provesto, INS officials asked him questions about his whereabouts and associates—whether he “subscribed to the Daily Worker” or “attended any movies at the Cinema Annex.” They also asked ten of what a reviewing district court would call “[d]o-you-know-a-certain-person’ question[s],” apparently seeking information about associates who shared his radical politics.[5]

Perhaps this should not surprise us. Historians have shown, in studies of the “Palmer Raids” of the 1920s to the War on Terror, that the government’s immigration power can be used to police the political activity of non-citizens, achieving what Dan Kanstroom calls “post-entry social control.”[6] Rachel Ida Buff’s recent history of the ACPFB, Against the Deportation Terror (2018), demonstrates how deeply immigration enforcement impacted immigrant lives, prompting them to connect immigration enforcement to the oppressive systems of racism, capitalism, and nationalism.[7]

I was surprised, though, by the ACPFB’s legal victories. Challenging the supervision power gave the ACPFB—by then entangled in its own fight against the Subversive Activities Control Board—a few unlikely wins. In several cases, two of which reached the Supreme Court, ACPFB-affiliated lawyers convinced judges to strike supervision orders as overly broad.[8] ACPFB lawyers also constrained the INS’s supervision power by advising their clients to claim the right against self-incrimination, limiting the government’s ability to prosecute migrants who violated their supervision orders. These were big wins. In 1957, ACPFB President Abner Green observed that the judicial limitations on the Justice Department’s supervision power were “the most serious set-back suffered by the Justice Department” in its enforcement of the Internal Security Act.

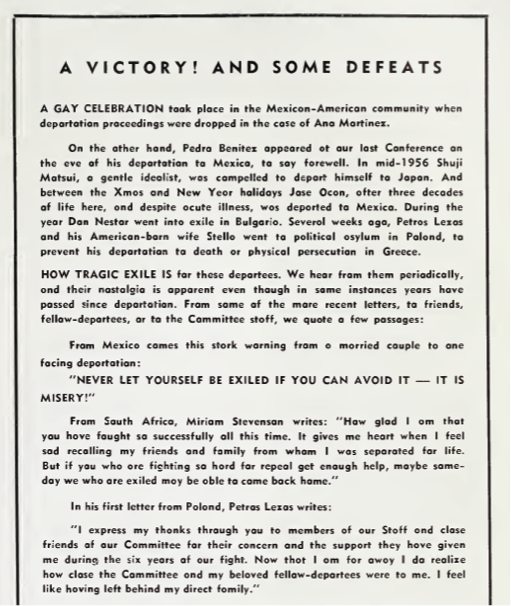

It would be wrong, though, to over-emphasize the ACPFB’s legal successes. The organization’s campaign against the Internal Security Act was more successful in limiting the government’s power to detain and institute parole orders than it was at challenging the deportation power. As the ACPFB noted, the INS successfully deported some radical non-citizens, and others left voluntarily. (In its publications, the ACPFB shared messages from deportees, who warned readers to “never let yourself be exiled if you can help it.”). In addition, the ACPFB failed in its efforts against “Operation Wetback,” in which hundreds of thousands of migrant laborers were deported to Mexico. On this front, the ACPFB’s political advocacy was unsuccessful, and their legal advocacy was pretty much non-existent, probably because—as one member observed—most migrant workers were deported so quickly that they had no “opportunity to seek legal counsel, notify relatives, or even pick up [their] belongings or collect [a] paycheck.”[9]

Buff points out that ideas about race and assimilability played into the ACPFB’s ability to represent radical non-citizens (the “red aliens,” most of whom were Eastern European, were still white). In the court, though, we should also look to accidents of geopolitics. The organization was able to help their clients fight supervision because those clients had been rendered “undeportable” when other countries refused to accept them. Without the power to deport non-citizens like Nat Yanish, the government had to detain and supervise them in America, opening itself to legal challenge. Mexican deportees—whose government consented to their return—were in a different situation. It seems, then, that the government’s invulnerable immigration authority rested on geopolitics as well as legal doctrine.

[1] Carol King & Ann Fagan Ginger, The McCarran Act and the Immigration Laws, 11 Law. Guild Rev. 128 (1951).

[2] Rachel Ida Buff, Against the Deportation Terror: Organizing for Immigrant Rights in the Twentieth Century (Philadelphia: Temple Univ. Press, 2017), 212.

[3] Ellen Schrecker’s “Immigration and Internal Security: Political Deportations during the McCarthy Era,” Science & Society 60, no. 4 (1996), offers one of the most detailed treatments of immigration enforcement under the Internal Security Act. After I finished my research, Julia Rose Kraut published Threat of Dissent, which connects ideological deportation under the Act (or “McCarranism”) to the long history of ideological deportation and exclusion. Julia Rose Kraut, Threat of Dissent: A History of Ideological Exclusion and Deportation in the United States (Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2020). Diving into the ACPFB’s records—especially those of its California-based lawyers—allowed me to build on Schrecker and Kraut by discussing the ACPFB’s efforts to fight deportation drives like Operation Wetback.

[4] Ann Fagan Ginger, Carol Weiss King, Human Rights Lawyer, 1895-1952 (Louisville, CO: University Press of Colorado, 1993), 511.

[5] United States v. Witkovich, 140 F. Supp. 815 (N.D. Ill. 1956).

[6] Dan Kanstroom, Deportation Nation: Outsiders in American History (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007).

[7] Rachel Ida Buff, Against the Deportation Terror: Organizing for Immigrant Rights in the Twentieth Century (Philadelphia: Temple Univ. Press, 2017).

[8] United States v. Witkovich, 353 U.S. 194 (1957); Barton v. Sentner, 353 U.S. 963 (1957) (per curiam).

[9] Journal for 1957 (issued for the 7th annual conference of the Los Angeles Committee for Protection of Foreign Born, April 6, 1957).