Ed. Note: This piece is part of The Docket’s initiative, A Focus on Undergraduate Scholarship, which aims to spotlight outstanding legal history projects being done by undergraduate students.

I. Introduction

Charles Sumner cannot be accused of having an unwarranted consideration for the virtues of consistency. The New Englander Sumner of the 1840s advocated for sectionalist interests so long as they provided a strong counter to the Southern warmongering and slave-owning desires, while the nationalist Sumner of the 1850s championed the federal government as far as it committed itself to limiting slavery’s growth and then eradicating it. The strict constructionist Sumner of 1855 advocated for a narrow construction of the Constitution in discrediting the Fugitive Slave Act, while the Sumner of the 1860s and 1870s demanded an elastic construction for carrying out Reconstruction and ensuring equal rights.

Despite these swings in his interpretive philosophy and party switches, Sumner’s thought was consistent, founded on an integral idealism that remained constant despite politics’ vicissitudes. “His partisanship … served as a means to advance moral ends.”[1]

If his inconsistencies make the search for firm guiding principles hard, it is muddled more by Sumner’s wide range of works. He was an illustrious and hardworking scholar-statesman and lawyer, serving as Senator from Massachusetts for twenty-three years.[2] His thought is thus not confined to an era or selection of works; instead, it must be extracted from a wide appraisal of his speeches, papers, and letters. These show that Sumner’s constitutional thought always followed the Declaration of Independence and its vision of life, liberty, and government built on the consent of the governed.

II. The Bridge Between Nationalism and Sectionalism

Since youth, Sumner was driven by “idealism, his faith in human nature, and the hope for the future.”[3] It was thus logical for him to have an adherence to natural law, which “is nothing more than those rules which human reason deduces from the various relations of man, to form his character, and regulate his conduct, and thereby insure his permanent happiness.”[4] It was a philosophy that highlighted doing good to others and abrogating the rule of the strong; his steadfast belief in natural rights philosophy supplemented this, which “emphasized individual rights and freedoms and looked to the equality of all men” in both moral commitments and civil rights[5] These underlying principles help explain Sumner’s elevation of and devotion to the Declaration, a document built on natural law and natural rights.[6]

Sumner was at heart a nationalist and institutionalist, committed to building a United States as a nation under the Declaration. In 1846, he defended his decision to join the Whig Party because it was “the party of Freedom,” able “to carry out fully and practically the principles of our institutions.”[7] He saw in it a dedication to the Declaration and its “vital truths of Freedom, especially that great truth, ‘that all men are created equal.’ ”[8] He also valued the party’s “reverence [for] the Constitution,” and he thought it “s[ought] to guard it against infractions, believing that under the Constitution Freedom can be best preserved.”[9] Above all, the Whigs “s[ought] to advance their country rather than individuals, and to promote the welfare of the people rather than of leaders,” which included “show[ing] [less] indifference to the Constitution or the Union” and “preserv[ing] the great principles of Truth, Right, Freedom, and Humanity.”[10]

This meant Sumner was also a conservative, but not today’s conservative. Instead, he viewed “true conservatism” as the quest for progress “through responsible means” and the quest for “the cultural and humanitarian improvement of society” via already-formed institutions and processes.[11] His views on nationalism and conservatism thus required using the federal government to combat what he saw as the maladies preventing his ideal republic.[12] But Sumner did not wholeheartedly champion other Whig causes, like the party’s elevation of property and business as conducive to a more cohesive, because the Whigs provided only a temporary vessel through which he could build his desired utopia.[13] His main cause remained to redeem the Declaration and its emphasis on life, liberty, and government by consent of the governed. He wanted the Whigs to counter what he saw as an expansionist South. Slavery “assumes at pleasure to build up new slaveholding States, striving perpetually to widen its area, while professing to extend the area of Freedom.”[14] Sumner’s end goal with the Whigs was thus to undo slavery.

But by 1848, the Whig Party had thrown away “every chance to disclaim complicity” with slavery.[15] Since the party departed from his constitutional vision, he, in turn, departed from the party and helped form and joined the Free Soil Party in 1848.[16] There, he stuck to his views on conservatism and the Constitution. But now, rather than advocating for a straight nationalist outlook, Sumner focused on sectional resistance to slavery’s threatened expansion. This switch is reflected in a letter commemorating the Ordinance of Freedom (Northwest Ordinance) in 1849. There, Sumner pleaded with his audience:

Let us all strive, with united power, to extend the beneficent Ordinance over the territories of our country. So doing, we must take from its original authors something of their devotion to its great conservative truth…. The National Government has been for a long time controlled by Slavery. It must be emancipated immediately.[17]

This commitment to the Declaration also shows his sectionalism rooted in preventing slavery’s expansion, as he called for a “regenerated Democracy of the North, which spurns the mockery of a Republic, with professions of Freedom on the lips, while the chains of Slavery clank in the Capitol!”[18] Sumner had witnessed Congress balk at the Wilmot Proviso, a measure to outlaw slavery in the territories acquired through the Mexican-American War (California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming).[19] So the nation’s clashing interests, the euphoria over manifest destiny combined with the Southern commitment to slavery, threatened Sumner’s utopian outlook. And so, he railed against the “mockery of a Republic” professed by the South and its intended expansion of slavery through popular sovereignty.[20] For Sumner, Northern Territories and States needed to counter what he saw as a slavery epidemic.[21] Sumner’s Free Soil Party “represent[ed] the great doctrines of Human Rights, as enunciated in our Declaration of Independence, and inspired by a truly democratic sentiment, now assembled here under the name of the Free Democracy.”[22] Despite later switching once more to start and join the Republican Party, Sumner would remain forever committed to these principles.

In 1852, Sumner again revisited nationalist themes, but with a sectionalist kick to them. In a letter to the Free Soil Convention at Worcester, Massachusetts, Sumner deplored both Democrats and Whigs for having “trampled on the Declaration of Independence.”[23] He also responded to the accusations of sectionalism hurled at him and the Free Soil Party by the “Slave Power”: “According to the true spirit of the Constitution and the sentiments of the Fathers, Freedom, and not Slavery, is national, while Slavery, and not Freedom, is sectional.”[24] He called for “upholding Freedom everywhere under the National Government.”[25] But if that could not be achieved, Sumner wished to do all he could to redeem the Declaration’s promises, even if it entailed serving the North’s interests. “Better be where Freedom is, though in a small minority or alone, than with Slavery, though surrounded by multitudes, whether Whigs or Democrats, contending merely for office and place.”[26]

These are not inconsistencies: Sumner wished to rid the nation of slavery and activate what he saw as the dormant or abrogated promises of the Declaration. If achieving so required working for national interests, then that was the course he adopted; if it required a more sectional approach, that was the course he adopted.

III. Guaranteeing Liberty through the Constitution: The Letter v. The Spirit

Sumner’s juggling of nationalism and sectionalism was not the only required balancing act during this turbulent era. To realize his constitutional utopia, he also alternated between strict (or adherence to the text and the founding materials concerning the Constitution) and liberal (considering context and purpose) constructions of the Constitution.

In an 1855 speech, and now a Senator, Sumner sought to overturn an amendment to the Fugitive Slave Act (and the Act itself), which would have given federal officials the authority to remove fugitive slaves from state courts to United States Circuit Courts, removing them from the safe havens found in the north.[27] Sumner saw the amendment as a violation of states’ rights, but beyond that, he saw the Fugitive Slave Act itself as crafted “in defiance of the Constitution, and in utter disregard of every sentiment of justice and humanity.”[28] Because of this, he urged it “be treated as an outlaw. It may have the form of legislation, but it lacks every essential element of law….”[29] He challenged fellow Senators to point to “the clause, sentence, or word in the Constitution which gives to Congress any power to legislate on this subject.”[30] Here, he called for a strict construction of the Constitution since a broader one would have given Congress the ability it had originally exercised when passing the Act.[31] Using a strict construction, he rejected assertions that Congress’s power stemmed from the Constitution’s Fugitive Clause.[32] And he chastised those who called for a liberal construction for the Fugitive Clause yet refused to apply the same to the Comity Clause:

Congress, in abstaining from all exercise of power under the [Comity Clause], when required to protect the liberty of the colored citizens, while assuming power under the [Fugitive Clause] … shows an inconsistency, which becomes more monstrous when it is considered that in the one case the general and commanding interests of Liberty are neglected, while in the other the peculiar and subordinate interests of Slavery are carefully assured.[33]

For Sumner, looking at “the express words” of the Comity Clause, coupled with the assertions of the Tenth Amendment, revealed that since Congress had no power to secure “the general and commanding interests of Liberty,” it also lacked the power to pass the Fugitive Slave Act—Congress’s enactment of the latter seized undelegated powers and violated the powers reserved to the States or the people.[34]

Using a narrow construction, Sumner revisited the sectionalist arguments. He pointed to South Carolina’s denying the application of the Comity Clause to African-American citizens of other States and asserted that other States could likewise abrogate the Fugitive Slave Act and the Fugitive Clause.[35] And he railed against other States’ attempt to breakdown Northern resistance by toughening the Fugitive Slave Act: “And yet …, in zeal for this enormity, Senators announce their purpose to break down the recent legislation of States, calculated to shield the liberty of the citizen.”[36] Following this, Sumner revealed his constitutional vision as one in which “Liberty is placed before Slavery,” which meant forming a Northern blockade against the Fugitive Slave Act by granting once-enslaved individuals protections, like relief under habeas corpus so that they could obtain freedom through state laws.[37] He also explained why he adopted sectional approaches despite being committed to the nation: “[L]et me say that I look with no pleasure on any possibility of conflict between the two jurisdictions of State and Nation; but I trust, that, if the interests of Freedom so require, the States will not hesitate.”[38] He added that his National Government was one “of Freedom, having nothing to do with Slavery. This is the doctrine I have ever maintained, and am happy to find recognized in form.”[39] He also placed high trust in the courts to vindicate his constitutional theory stating, “the Constitution of my country contains no words out of which Slavery, or the power to support Slavery, can be derived.”[40] But again, if his views of the National Government and Constitution were impossible, he would approach remedies through sectional means “until Slavery is driven from its usurped foothold, and Freedom is made national instead of sectional.”[41]

The Supreme Court’s decision in Scott v. Sandford (holding that African Americans, regardless of status, had no rights under the Constitution)made Sumner’s constitutional vision improbable if not outright impossible—in arguing against the Fugitive Slave Act, he believed that the Court would side with him that slavery had no place in the Constitution.[42] It was thus not until after Abraham Lincoln’s election and the Civil War that his designs could be implemented.

Sumner wanted a Reconstruction that accomplished the Declaration’s aspirations. In his 1865 eulogy of President Lincoln, he asserted that “the [Civil War] will have failed, unless it consummates all the original promises of the Declaration our fathers took upon their lips when they became a Nation.”[43] This required a potent National Government—one that supplemented the Constitution’s text with the Declaration’s goals. Sumner’s constitutional vision thus changed from one adhering to the text to one going beyond it.

A good starting point for Sumner’s post-Reconstruction constitutional thought is the eulogy. Here, Sumner called for a “New Nation,” adhering to the Gettysburg Address, “with the Equality of All Men as its frontlet.”[44] This in turn warranted destroying slavery’s underlying aspects, like the racial caste it had formed, through bold measures.[45] These measures, like the Federal Government ensuring equal voting rights, needed a broad interpretation of the Constitution following “first, the law of reason and of Nature, and, secondly, the Constitution, not only in its text, but in the light of the Declaration.”[46] Sumner elaborated on this new method of lawmaking and constitutional interpretation:

By reason and Nature there can be no denial of rights on account of color; and we can do nothing thus irrational and unnatural. By the Constitution it is stipulated that ‘the United States shall guaranty to every State a republican form of government’; but the meaning of this guaranty must be found in the birthday Declaration of the Republic, which is the controlling preamble of the Constitution.[47]

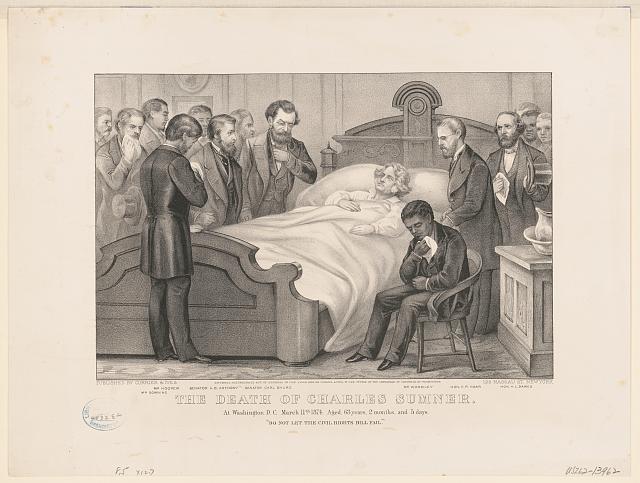

He built on this position in two letters. In a 4 July 1865 letter to Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, Sumner claimed that the federal power to pursue a potent Reconstruction in the South derived from Congress’s war powers and also from the Guarantee Clause.[48] In a letter to his friend Francis Lieber on 12 October 1865, Sumner explained his views on using the Guarantee Clause: “[w]ords receive expansion and elevation with time. Our fathers builded [sic] wiser than they knew. Did they simply mean a guarantee against a king? Something more … all of which was not fully revealed to themselves, but which we must now declare in the light of our institutions…. Let us affix a meaning which will make us an example and will elevate mankind.”[49] This broad construction undergirded Sumner’s fight for equality and justice during Reconstruction, a fight that “would dominate the remaining years” of Sumner’s life, dying at the age of 63 in 1874.[50]

In a Senate speech proposing a bill to secure equality in civil rights, Sumner called for increased congressional power to protect human rights, considering Congress’s power “supreme.”[51] Most importantly, now that emancipation had been achieved, he wanted to restore “the Declaration of Independence, and the guaranty of a republican government” through the franchise.[52] “Equal Rights of All, at the ballot-box as in the court-room. This is the Great Guaranty without which all other guaranties will fail. This is the sole solution of present troubles and anxieties. This is the only sufficient assurance of peace and reconciliation.”[53] Lacking an amendment promising what he saw as “the Great Guaranty,” Sumner thought Congress’s powers to execute it were housed in the Guarantee Clause and the Thirteenth Amendment’s Enforcement Clause of the Constitution.[54] He also recast the Constitution as a democratic document that called for the granting of equal political rights despite the Constitution having no such clause, claiming that “[w]hatever is required for the national safety”—in this case, voting rights—“is constitutional.”[55] He added that not using Congress’s powers to achieve equality at the ballot box amounted to “expos[ing] your country to incalculable calamity.”[56] So voting was necessary for the Republic’s safety and to complete Emancipation.[57]

This meant undoing any “exclusion … founded on color.”[58] Here was a break from his strict construction championed in 1855, especially since the Constitution holds that States prescribe their election rules.[59]

To combat this states’-rights ideology, Sumner insisted that nowhere in the Constitution was someone’s skin color made dispositive of how much political agency they had; he considered a version of the Constitution contrary to this view as “oligarchical.”[60] But Sumner knew that dismantling nearly a hundred years of discrimination required a great effort from Congress, and that he also confronted overcoming the Supreme Court’s decision in Dred Scott, so he told the Senate that “[i]n affixing the proper meaning to the [Guarantee Clause], and determining what is a ‘republican form of government,’ you act as a court in the last resort, from which there is no appeal. You are sole and exclusive judges…. You may raise the Republic to majestic heights of justice and truth.”[61] He thought allocating political rights would cause the United States to “cease to be a patchwork where different States vary in the rights they accord, and will become a Plural Unit, with one Constitution, one liberty, and one franchise,” so that “the Republic will be of such renown and virtue that all at home or abroad who bear the American name may exclaim with more than Roman pride, ‘I am an American citizen!’ ”[62] A wider view of the Constitution enabled Sumner’s commitment to his nationalist roots.

In 1869, as Congress considered the Fifteenth Amendment, Sumner again advocated for an elastic interpretation of the Constitution when he called for Congress to undo the caste system in the South.[63] He favored a bill over an amendment because it was “the simplest process, producing the desired result with the greatest economy of time force.”[64] This meant increasing Congress’s powers to reach the deepest wellsprings of “Inequality and Caste, whether civil or political.”[65] He also preferred the bill because, unlike with an amendment, States could not fail to ratify it.[66] This time, rather than championing states’ rights as he had done in opposing the amendment to the Fugitive Slave Act, Sumner derided them as an “alias” for discrimination embedded in the Constitution.[67] To break away from “an interpretation of the National Constitution supplied by the upholders of Slavery,” Sumner maintained that “State Rights shall yield to Human Rights…. Beyond all question, the true rule under the National Constitution, especially since [the addition of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments], is, that anything for Human Rights is constitutional.”[68]

To implement that principle, Sumner wished to limit a State’s power to regulate its internal affairs: “The State is local in character, not universal…. [W]hatever is universal belongs to the Nation. But what can be more universal that the Rights of Man?”[69] This demanded that the Constitution “be interpreted always so that Human Rights shall not suffer.”[70] But in this same speech, Sumner reverted to a strict construction to counter the claim that a State’s ability to regulate its elections gave it the power to discriminate based on race—he pointed to the absence of “color” in the Constitution.[71] After this, however, he broadened his constitutional interpretation to say that the Federal Government’s ability to secure suffrage for all rested on the Declaration, “where it is expressly announced that all men are equal in rights, and that just government stands only on the consent of the governed.”[72] Echoing Chief Justice Marshall in McCulloch v. Maryland, Sumner declared that “Congress, when intrusted [sic] with any power, is at liberty to select the ‘means for its execution.”[73] For the first time ever, Congress was elevated to have complete and exclusive jurisdiction to remedy even the most local of discriminations—Reconstruction had provided a rebirth of American democracy, and Sumner did not want the nation to miss this “golden moment” to redeem the Declaration’s promises.[74] This meant “establish[ing] absolute political and civil equality through the land.”[75]

But Sumner’s interpretative vision (and his utopia) never fully materialized. A year after his assertion that Congress could eradicate the caste and oligarchy forming in the South, he introduced a civil rights bill—potent in both scope and task—derived from the awesome powers granted to the Federal Government through the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth (Reconstruction) Amendments.[76] This Act proscribed race-based discrimination in public accommodations and services, including railroads, hotels, steamboats, public schools, juries, churches, and restaurants.[77] (In the Republic’s history, no other federal statute had attempted this.[78]) It stalled in Senate committees until it was signed into law in 1875 (after Sumner’s death).[79] By then, the Act’s opponents had stripped away its provisions on schools and churches, charging that Sumner’s vision granted too much power to the Federal Government through an improper interpretation of the Constitution.[80] And in 1883, the Supreme Court invalidated the Act as an improper exercise of Congress’s powers because it barred private entities’ actions rather than states.’[81] This ruling repudiated Sumner’s view that, under the Declaration, constitutional interpretation need not be circumscribed “by the hallowed precedents of the past” but account for “the social realities of the present.”[82]

IV. Toward the Sumnerian Utopia

Charles Sumner was idiosyncratic. He was deeply immersed in legal theory and practice, but his ideal society required interpreting the Constitution through the Declaration of Independence.[83] This has been called an “incongruit[y],”[84] but it was not—instead, it reflects Sumner’s ultimate dedication to the Declaration. As Sumner put it while eulogizing President Lincoln: “[I]f the pledges of the Declaration, which the Rebellion openly assailed, are left unredeemed, then have blood and treasure been lavished for nought [sic].”[85] Through the Declaration, he thought, “there can be no denial of rights on account of color.”[86] The United States thus “when called to enforce the [guarantee of a republican government], must insist on the equality of all before the law, and the consent of the governed.”[87]

Sumner’s United States was one where “the ideas of the Declaration of Independence” were “recogni[zed] … everywhere throughout the country.”[88] To achieve this, Sumner pressed for an enlargement of the Federal Government’s powers—through it alone could equality before the law be achieved.[89] This entailed rewriting the Constitution since it had before been construed as a document favorable to States, protecting slavery and all forms of discrimination.[90] This is why in 1869, when most Republicans considered Reconstruction to have been completed, Sumner disagreed.[91] Guaranteeing racial equality demanded the Federal Government’s constant and powerful hand.

Yet his utopia called for more than equal rights and a strong National Government tasked with protecting them. It also needed a noble, efficient government. “The country desires an example for the youth of the land, where intelligence shall blend with character, and both be elevated by a constant sense of duty with unselfish devotion to the public weal.”[92] So in his final days, Sumner dedicated himself—apart from securing equality for all before the law—to combating the Grant Administration’s corruption, which meant turning on his own Republican Party.[93] This included decrying the administration’s 1870 to 1871 plan to annex the Dominican Republic, which Sumner thought would form a colonial relationship.[94] Because of Sumner, the planned annexation failed.[95] But this cost Sumner politically, and he was ousted from chairing the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (which he had chaired since 1861).[96]

After this, Sumner’s political career and health sunk.[97] He died without having realized his envisioned utopia. After his death, the nation regressed from the political victories it had achieved during his time. In 1877, for example, the compromise that granted Rutherford B. Hayes the White House and the South its state rights ended Reconstruction, undoing much of the political rights and equality achieved through it.[98] In 1883, as discussed above, the Supreme Court rolled back the civil rights Sumner’s bill protected.[99] In 1896, the Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that state-imposed separate accommodations were constitutional under the Fourteenth Amendment so long as they were “equal.”[100] This ruling restored States’ ability to enforce old and new discrimination schemes, including racial segregation, even if they seemed inconsistent with the Reconstruction Amendments: “Governments regularly used facially neutral laws … to perpetuate racial inequality.”[101]

But Sumner’s utopia came closest into being during the 1950s and 1960s, when the nation—once again through blood—toiled to redeem the Declaration’s and the Reconstruction Amendments’ promises. In 1954, the Supreme Court overturned Plessy’s separate-but-equal doctrine and ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment’s commands guaranteed equal access to public education.[102] Here, the Court reflected Sumner’s convictions that the Constitution need not always abide by “the idol of precedent” but could instead look to “changing conditions and new developments in society.”[103] Yet the most watershed events came in the 1960s when the Federal Government undertook the guaranteeing of equality Sumner championed. In 1964, Congress passed a Civil Rights Act that borrowed much from Sumner’s—this included using the Federal Government’s power to “end segregation in public places and in education” and set up agencies that implemented other equality-seeking goals, like equal opportunities in employment.[104] And in 1965, the greatest achievement heeding the Declaration’s vision was signed into law: The Voting Rights Act combined democracy with racial equality, thus “achiev[ing] the political freedom that had been promised” to African Americans during Reconstruction.[105] On top of providing an equal shot at the American political process, the Voting Rights Act also helped African Americans “in holding public office” by ensuring that congressional districts were not drawn in ways that diluted their votes.[106] These two grand measures carried out Sumner’s vision of abolishing slavery “not in form only, but in substance, so that … all shall be Equal before the Law” and reviving the Declaration’s long-dormant ideals.[107]

Those achievements, however, have been abrogated. In 2013, the Supreme Court invalidated the Voting Rights Act’s enforcement mechanism that prevented localities from enacting discriminatory laws.[108] After, States again adopted policies that hinder minorities’ ability to have an equal chance at the ballot box.[109]

The Sumnerian utopia remains a vision. Achieving it requires the Sumnerian leader to interpret the Constitution considering the Declaration, with the Declaration providing “the substance of the law” and the Constitution “the framework for upholding it.”[110] So the Declaration must be elevated from “historical relic” to a tool for constitutional elucidation if not interpretation.[111] Under this, democracy-bolstering measures like the Voting Rights Act would not be restrained by the cover of states’ rights. “State Rights shall yield to Human Rights, and the Nation be exalted as the bulwark of all. This will be the crowning victory of the war. Beyond all question, the true rule under the National Constitution, especially since its additional Amendments, is, that anything for Human Rights is constitutional.”[112] For the Sumnerian leader, the Declaration becomes the “sovereign rule of [constitutional] interpretation.”[113]

But effecting change does not mean undoing institutions and processes; instead, the Sumnerian leader must work through them to achieve progress. This is the only way in which the Declaration’s aspirations can be achieved. Most importantly, the Sumnerian leader must not lean into politics’ changes; they must be guided by reason and the Declaration’s ideals. Sumner failed to build his utopia during the United States of the 1840s, 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s because his times were fraught with conflict and polarization—his idealism was out of step with the age. So too is the United States of the 2010s and 2020s, but they need not be if leaders heed the Sumnerian creed: be true to the Declaration of Independence.

[1] Frederick J. Blue, Charles Sumner and the Conscience of the North (Arlington Heights, IL: Harlan Davidson, 1994), 210.

[2] Anne-Marie Taylor, Young Charles Sumner and the Legacy of the American Enlightenment, 1811-1851 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001), 2.

[3] Taylor, Young Charles Sumner, 39.

[4] Ibid., 52.

[5] Ibid., 52-3.

[6] Alexander Tsesis, “The Declaration of Independence and Constitutional Interpretation,” Southern California Law Review 89, (March 2016): 372-73 (noting the “[i]nclusion of broadly understood natural rights principles in the Declaration” and how so urged Framers like Madison and Hamilton to resist the idea of the Bill of Rights); Donald S. Lutz, “The Declaration of Independence As Part of an American National Compact,” Journal of Federalism 19, (Winter 1989): 49 (at the time, “those reading Jefferson’s words [in the Declaration] would read them as meaning that all men have equal liberty to give and withhold consent, that in civil society all men by birth have the same rights in that society while they are members, and that any given people have the same right to self-government as any other people”); Ronald B. Jager, “Charles Sumner, the Constitution, and the Civil Rights Act of 1875,” New England Quarterly 42, no. 3 (September 1969): 350-72 (describing Sumner’s adherence to the Declaration in the context of the Civil Rights Act of 1875).

[7] Charles Sumner, “Antislavery Duties of the Whig Party (September 23, 1846),” in His Complete Works (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1900), Statesman Edition, vol. I: 305 (hereafter Works).

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid., 306.

[11] Taylor, Young Charles Sumner, 70.

[12] Ibid., 64.

[13] Ibid., 68-9.

[14] Sumner, “Antislavery Duties of the Whig Party,” 307.

[15] Taylor, Young Charles Sumner, 246.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Charles Sumner, “Be True to the Declaration of Independence (July 6, 1849),” in Works, vol. III: 2.

[18] Ibid., 2-3.

[19] Kate Masur, Until Justice Be Done: America’s First Civil Rights Movement, from the Revolution to Reconstruction (New York: W. W. Norton, 2021), 215, 232.

[20] Sumner, “Be True to the Declaration,” 3.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Charles Sumner, “Sympathy with the Rights of Man Everywhere (October 27, 1851),” in Works, vol. III, 168.

[23] Charles Sumner, “Union Against the Sectionalism of Slavery (July 6, 1852),” in Works, vol. III, 241.

[24] Ibid., 242 (emphases in original).

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Charles Sumner, “Demands of Freedom: Repeal of the Fugitive Slave Act (February 23, 1855),” in Works, vol. IV, 333.

[28] Ibid., 337.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid., 339-40.

[34] Ibid., 341; U. S. Const. Amend. X.

[35] Sumner, “Demands of Freedom,” 341-42.

[36] Ibid., 343.

[37] Ibid., 343-44.

[38] Ibid., 344.

[39] Ibid., 345.

[40] Ibid., 346.

[41] Ibid., 347 (emphases in original).

[42] Ibid., 346; Masur, Until Justice Be Done, 255-56 (explaining the ruling in detail).

[43] Charles Sumner, “Promises of the Declaration of Independence, and Abraham Lincoln (June 1, 1865),” in Works, vol. XII: 239.

[44] Sumner, “Promises of the Declaration,” 241-42.

[45] Ibid., 299.

[46] Ibid., 294.

[47] Ibid., 295.

[48] “Letter to Gideon Welles (4 July 1865),” in The Selected Letters of Charles Sumner, ed. Beverly Wilson Palmer, vol. II: 314.

[49] Edward L. Pierce, Memoir and Letters of Charles Sumner (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1893), vol. IV: 258-59.

[50] Blue, Charles Sumner and the Conscience of the North, 162.

[51] Edward L. Pierce, Memoir and Letters,vol. IV: 280.

[52] Charles Sumner, “Equal Rights of All (February 5-6, 1866),” in Works, vol. XIII: 121.

[53] Ibid., 124.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Ibid., 129.

[56] Ibid., 130.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Ibid., 130-31.

[59] Ibid.,

[60] Ibid., 136.

[61] Ibid., 138.

[62] Ibid., 231-32.

[63] Charles Sumner, “Powers of Congress to Prohibit Inequality, Caste, and Oligarchy (February 5, 1869),” in Works, vol. XVII: 35

[64] Ibid.

[65] Ibid., 36.

[66] Blue, Sumner and the Conscience of the North, 181.

[67] Sumner, “Powers of Congress,” 37.

[68] Ibid., 37-8 (emphasis in original).

[69] Ibid., 39.

[70] Ibid., 40.

[71] Ibid., 42.

[72] Ibid., 43.

[73] Ibid., 46. Cf. McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U. S. 316, 421 (1819) (“Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consist with the letter and spirit of the constitution, are constitutional”).

[74] See Eric Foner, Reconstruction: 1863-1877 (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 230; Eric Foner, The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2019), 2 (calling the Civil War and Reconstruction the moments that started “making the Constitution what it might have been if ‘We the People’ … had been more fully represented at Philadelphia”).

[75] Pierce, Memoir and Letters, vol. IV: 415.

[76] Foner, The Second Founding, 139.

[77] Ibid.

[78] Ibid., 141.

[79] Ibid.

[80] Ibid.

[81] Ibid., 151.

[82] Ronald B. Jager, “Sumner and the Constitution,” 350.

[83] Ibid., 354-57.

[84] Ibid., 354

[85] Sumner, “Promises of the Declaration of Independence,” 292.

[86] Ibid.

[87] Ibid., 295 (emphases in original).

[88] Charles Sumner, “Ideas of the Declaration of Independence: Letter to the Mayor of Boston, on the Celebration of National Independence (July 4, 1865),” in Works, vol. XII: 297.

[89] Charles Sumner, “Enfranchisement and Protection of Freedmen (December 20, 1865),” in Works, vol. XIII: 56.

[90] Foner, The Second Founding, 9, 15-17.

[91] Blue, Charles Sumner and the Conscience of the North, 202.

[92] Charles Sumner, “First in War, First in Nepotism,” Lapham’s Quarterly, 1872, https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/scandal/first-war-first-nepotism.

[93] Blue, Charles Sumner and the Conscience of the North, 198-201, 210-11.

[94]Dennis Hidalgo, “Charles Sumner and the Annexation of the Dominican Republic,” Itinerario 21, no. 2 (July 1997): 57-8; see David H. Donald, Charles Sumner and the Rights of Man (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1970), 438-44.

[95] Donald, Sumner and the Rights of Man, 444.

[96] Ibid., 444-45.

[97] Ibid., 579-87.

[98] Foner, Reconstruction, 575-87.

[99] Foner, The Second Founding, 151.

[100] 163 U. S. 537 (1896).

[101] Masur, Until Justice Be Done, 347, 354.

[102] Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954).

[103] Jager, “Charles Sumner and the Constitution,” 372.

[104] “The Civil Rights Act of 1964,” in Charting Democracy in America: Landmarks from History and Political Thought eds. Alfred Fernbach and Julian Bishko (Washington, DC: American University Press, 1995): 545-49 (hereafter Charting Democracy in America).

[105] Gary May, Bending Toward Justice: The Voting Rights and the Transformation of American Democracy (New York: Basic Books, 2013), 169.

[106] See “The Voting Rights Act of 1965,” in Charting Democracy in America, 556-58.

[107] Sumner, “Enfranchisement and Protection of Freedmen,” 61.

[108] Ari Berman, Give Us the Ballot: The Modern Struggle for Voting Rights in America (New York: Picador, 2016), 273-

[109] P.R. Lockhart, “How Shelby County v. Holder upended voting rights in America,” Vox, June 25, 2019, https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2019/6/25/18701277/shelby-county-v-holder-anniversary-voting-rights-suppression-congress.

[110] Alexander Tsesis, “Self-Government and the Declaration of Independence,” Cornell Law Review 67, no. 4 (May 2012): 702.

[111] Tsesis, “The Declaration and Constitutional Interpretation,” 370.

[112] Sumner, “Powers of Congress to Prohibit Inequality,” 37-8 (emphasis in original).

[113] Tsesis, “The Declaration and Constitutional Interpretation,” 370.