Ed. Note: In early 2023, Law and History Review published Hayden Bellenoit’s article, Legal Limbo and Caste Consternation: Determining Kayasthas’ Varna Rank in Indian Law Courts, 1860–1930 (vol. 41, no. 1). This spring, Bellenoit took the time to discuss his work with The Docket. Here is our discussion.

Thank you, Hayden, for taking the time to discuss your work with our readers! Let’s start with te beginnings of this project. Can you tell our readers how you first encountered the story about the Kayasthas’ varna rank.

I first stumbled across this story while I was completing my second monograph on colonial state formation and the role that Kayasthas scrobes played in providing the “fiscal teeth” of the early colonial state.[1] The last chapter of the book gave an overview of the social and cultural predicaments that Kayasthas faced in the later generations of colonial rule after the 1870s. Specifically, one of these was an at-times vitriolic debate regarding their caste rank and status which punctuated the press, caste reform debates and Kayastha publications. They referenced several court rulings that, in their eyes, were an affront to their honor, namely the 1884 Calcutta High Court case. It was referenced in so many places! But in finishing the monograph – because it was not the main focus – I did not go into much detail. A few years later I realized that this was an opportunity to explore an angle of Indian legal history that had not been examined: colonial law’s role in the formation of social and caste categories. There has been good work done by Mitra Sharafi[2], Julia Stephens[3] and Chandra Malampalli[4] on colonial law’s role in the formation of more monolithic ‘religious’ identities. But very little has been done on how colonial law shaped the construction of modern conceptions of caste. I therefore decided to dive into this topic and discovered a slew of cases that dealt – directly and indirectly – with the question of their caste rank.

In your article recently published in Law and History Review, the Calcutta High Court’s 1884 intervention plays a decisive role. Can you explain a bit about how that court worked and how it arrived at its decision?

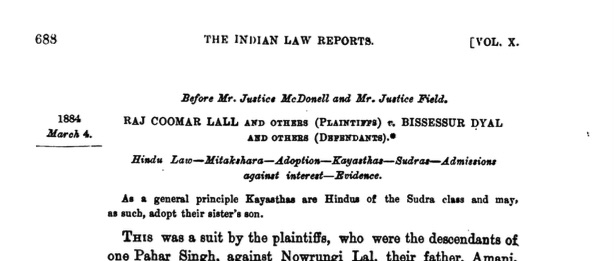

Let’s just say that I would not envy the Calcutta justices in 1884. This case – Raj Coomar Lall And Ors. vs Bissessur Dyal[5] – was actually the first one that made it a specific point to determine the caste rank of Kayasthas. The two cases I examined before this largely treated Kayasthas’ caste rank as incidental to the adjudication of fairly run-of-the-mill inheritance disputes. But the case before the Calcutta High Court was qualitatively different since it turned on whether Kayasthas belonged to the “twice-born” castes (that is, the top three groupings of Brahmins Kshatriyas and Vaishyas). For the purposes of brevity, the case was about an inheritance dispute that was tied up with an adoption that caught other family members off guard. The adopted son in question – Bissessur Dayal – claimed share of an inherited estate. The family faction that was against this specifically cited the Mitākṣarā “school” of Dharmaśāstra to argue that adopted sons are disqualified from shares of inheritance, as it was not permissible for “twice-born” castes. So perhaps ironically, the case was not initially concerned with varna rank. But when the plaintiff – Raj Kumar Lal – specifically cited the Mitākṣarā “school” of law, he had no idea what a flood gate he just opened.

The justices found an expedient way to adjudicate this case: simply determine the varna rank of Kayasthas! In fact they stated very clearly in the proceedings that the chief objective of the case was “to come to a proper decision of…whether the plaintiffs’ family…admitted to be Kayasthas…do belong to either of the three higher [twice-born] castes”. It did not get any simpler than that. What was particularly revealing about this case was that they consulted a wide variety of Indian-authored jurisprudence and European-authored colonial ethnographies. As I’ve argued in previous work, the latter tended to be greatly informed by the former, which meant a very high caste, Brahmanical legal flavor.[6] Specifically, there was one piece of Indian author jurisprudence that really swayed the justices: the Bengali legal scholar Shyamcharan Sarkar’s Vyavasthādarpaṇa (1867).[7] His legal treatise – upon which the Justices heavily leaned – argued that continuous, living ritual was the determining factor of a Hindu group’s caste rank and standing. And this was very intrusive detective work: the court asked whether Kayasthas practiced the rituals in customs of the upper three, “twice born” castes: did they wear the scared thread (janoi/janeev)? Did they perform the fire (homa) rituals? How long did they mourn for end-of-life rites (antyeṣṭi)? But what was really interesting is that the very “bookish” nature of British colonial law tended not to ask Kaysthas themselves whether they actually undertook these rituals: they mostly examined textual and written evidence, much of which was very Brahmanical and privileged high-caste norms. The Justices eventually ruled that since there was noticeable inconsistency regarding Kayasthas’ rituals, they could not be considered “twice-born”. They therefore were Shudras, which was a shock given their long history of literacy and state-employment since the 1500s. This was significant because this ruling was referenced not only in other areas of case law, but also by Kayastha organizations, and in particular their main organ the Kayasthas Samachar (later the Hindustan Review). It became the most commonly cited legal ruling by Kayastha advocates and critics.

Those attuned to the news in India today will know that the problem of caste is never too far from the headlines. Do you think that your research can teach us about contemporary debates about caste? And zooming out a bit, what would you like those who are non-experts in South Asian history to understand about the caste system and its persistence?

Regarding contemporary caste debates in India, I think this research can shed light on a few important dynamics. One, caste is not so much a “problem” as it is an ever-evolving social reality. Two, I think it is fair to say that contemporary debates about caste in India are still greatly shaped by the residual legacy of these “colonial classifications”. Colonial law – especially for what the British presumed (naively) was “Hindu law” – saw caste rank and hierarchy as a way of adjudicating legal disputes, particularly civil cases over inheritance, maintenance, alimony, et cetera. Specifically, much of the case law that deals with the Hindu family is concerned with distinguishing and delineating the 4 main caste ranks: Brahmins, Kshatriyas and Vaishyas, then Sudras. In colonial jurisprudence – both British and Indian-authored – made a very clear distinction between the customary rituals (and by extension legal rights) between the “twice-born” upper 3 castes and Sudras. And to inform their jurisprudence – as historians of India and Indian law have demonstrated – they referenced overwhelmingly the Shastras and the legal-jurisprudential commentarial tradition of Hinduism.[8] This has the effect of privileging a very high caste, Brahmanical way of interpreting “Hindu law”. And because colonial law created a looser template based on this 4-fold hierarchy called “varna”, this concordantly created categories of those who were “outside” this fold: untouchables/Dalits, scheduled tribes, scheduled criminal tribes, etc. And these categories – though they acquired different nomenclature – are still used in India for determining reservations and all the controversy that it has attracted since the 1950s and 60s. One can recall the 1990 riots that broke out over the Mandal Commission reports that effectively (end it should be noted controversially) estimated that over 50% of the Indian population could be categorized as “backward castes”. So these taxonomical categories persist. And you can see why certain caste groupings see a benefit in claiming a “backward” social rank so that they can accrue benefits from the state.

For those unfamiliar with India and South Asia, I think it is important to note some important background details. The term “caste” itself is not of Indian but of Portuguese and origin. It refers to “lineage,” and it was used by the Portuguese (and the Spanish) to distinguish themselves from indigenous peoples and mestizo/mixed race communities in their American and Asian colonies. It eventually traveled into the European lexicon and became the word we know today. But in India’s longer history, this term is a relatively recent arrival. The Indian-origin terms used historically were varna (the 4-fold theoretical occupational division of society laid out in the Rig Veda’s Purusha Sukta) and jati. The former referred to the theoretical 4-fold division of society and the latter means “birth”, which grew organically over thousands of years. It is rather like a family “bloodline”. In the long term though, this whole “system” has persisted because the categories became more fixed under colonial law and its courts, which were more likely to conclusively adjudicate and enforce decisions compared to previous legal regimes before the 1700s.

What’s next for you in terms of research and writing?

Right now, I am working on a few different articles. The first one is about a defamation suit that originated in Benares in the 1910s. It involved members of the merchant-trading Agarwal community, and is about a young man named Govind Das. He was temporarily outcaste from his community, upon which he filed a defamation suit against his caste headman (chaudhuri). It’s a singular case. But it is very rich in detail – particularly regarding the animated and colorful disputes within a caste organization. And it raises interesting questions about the intersection between colonial courts and panchayat jurisdiction.

The second project I am working on – which I think will start as a journal article but I have plans to turn it into a larger, third monograph – is a history of how colonial law categorizes and molds “caste” as a social institution in India over a longer period from the 1700s. There is an established historical literature that examines how modern conceptions of caste were shaped by Hindu reform movements, colonial ethnography and the census. But this project wants to widen the aperture of my recent article in Law & History Review[9] by looking not just at case law and a certain caste, but by examining how the broader imposition of a foreign legal “system” shaped modern caste dynamics beyond case law: what Indian authored jurisprudence argued about varna, ritual and the “twice-born” castes; how the legal profession in certain parts of India (namely Tamil country in the South) were dominated by Brahmins and other high castes; looking at how colonial law’s management of Hindu religious endowments and institutions created new discourses about what constituted the “essential” features of caste hierarchy and varna through temple entry disputes.

Your research for this article and your other works taken you to India and elsewhere. What’s been your favorite research moment so far?

It is hard to think of a specific research moment, but I think my most gratifying search experiences have been in two different countries: the UK and India. While at the SOAS Library in London one summer, I was astonished at how rich the open shelf Indian case law was.

I found so many topics that I would never have thought of and have given me lots of ideas for future research. In India, I think my most memorable research moments have been those encounters with Indians who showed such warm and kind appreciation for the work I was doing on their history. One specific example was with a Kayastha family. The family patriarch was a professor at Lucknow University and he graciously invited me to his home to meet his entire extended family. They were kind enough to actually share their family genealogy and history with me, which I drew upon for my book The Formation of the Colonial State. It was such a rich, colorful insight into the occupational history of a looser group of scribes and scholars with whom I have been continually fascinated and indeed grateful for sharing their histories.

[1] Hayden J. Bellenoit, The Formation of the Colonial State in India: Scribes, Paper and Taxes, 1760-1860 (Abingdon: Routledge, 2017)

[2] Mitra Sharafi, Law and Identity in Colonial South Asia: Parsi Legal Culture, 1772-1947 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014)

[3] Julia Stephens, Governing Islam: Law, Empire and Secularism in South Asia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018)

[4] Chandra Mallampalli, Race, Religion and Law in Colonial India: Trials of an Interracial Family (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011)

[5] Raj Coomar Lall And Ors. vs Bissessur Dyal And Ors., 4 March 1884, Indian Law Reports, Calcutta (ILR, Cal), 10 Cal 1884

[6] Hayden J. Bellenoit, “Flesh, booze and (contested) lineages: Kayasthas, caste and colonial ethnography, 1870-1930”, South Asian History and Culture (Oxford: Taylor & Francis), 13:2, 157-179

[7] S. Sircar, Vyavashtá Darpana: A Digest of Hindu Law as Current in Bengal (Calcutta: Girish-Vidyaratna Press, 1867)

[8] Jonathan Duncan Derrett, Religion, Law and the State in India (London: Faber & Faber, 1968); Bernard Cohn, “Law and the Colonial State,” in History of Power in the Study of Law: New Directions in Legal Anthropology, ed. June Starr and Jane Collier (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1989).

[9] Hayden J. Bellenoit, “Legal Limbo and Caste Consternation: Determining Kayasthas’ Varna Rank in Indian Law Courts, 1860–1930,” Law and History Review (2023): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0738248023000056