“I’m sorry Casey Martin has trouble walking, but he should not be given an advantage because of his disability,” David Cathey of Fayetteville, GA, wrote to Justice John Paul Stevens in May of 2001. “If he wants to play pro golf on his terms, then he should start a professional association that permits the use of golf carts.”[1] Dr. Howard Mindell agreed. “This fatigue influences my game, golf is impossible anyway, it is a matter of millimeters, and every little factor counts … I suppose the NBA …. should offer ladders so short people can dunk, they are disabled on a relative scale.”[2] “It’s called help, and in golf, it’s not allowed,” noted Washington Post reporter Sally Jenkins who described the Supreme Court’s 7-2 decision in PGA Tour, Inc. v Martin, as “wrongheaded.”[3]

Golfer Casey Martin was born with Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber Syndrome, a rare disorder that prevented blood from circulating in his right leg often causing blood to pool in its lower portion. A painful and taxing condition, it also resulted in Martin developing “a dangerously fragile right shinbone.”[4] Despite this condition, Martin competed professionally in golf tournaments during the mid to late 1990s. In 1997, he challenged in court the PGA’s denial of his request for use of a cart during PGA competitions, as what he deemed a “reasonable accommodation” under the Americans with Disabilities Act.[5]

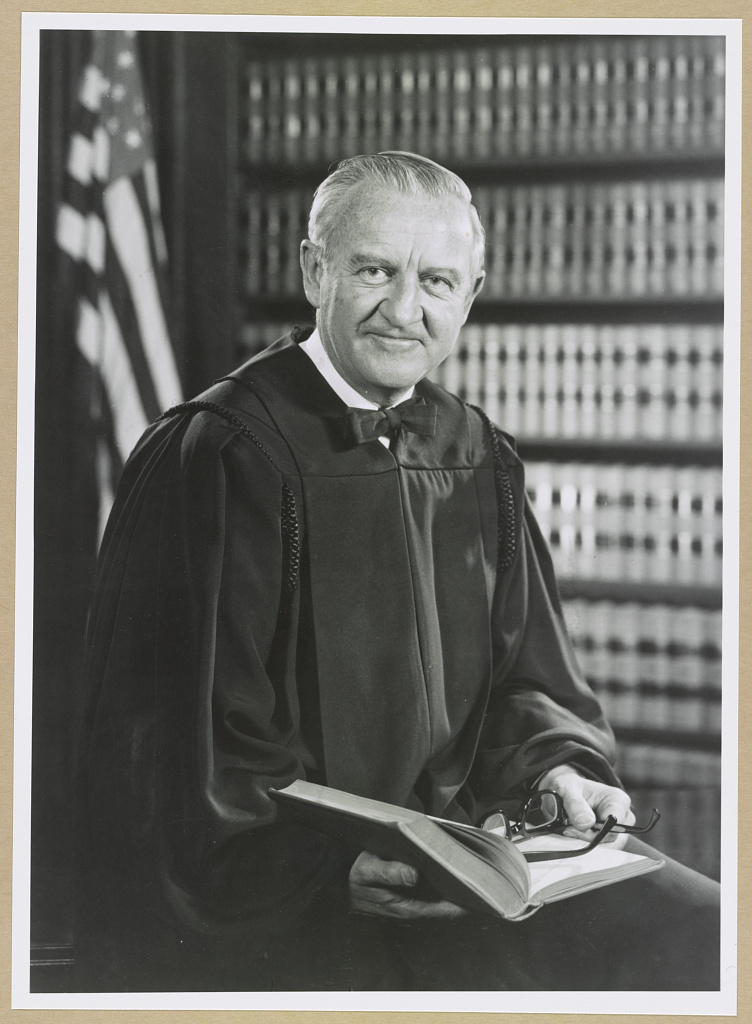

Critics emerged quickly. “This man got into Stanford,” wrote longtime Boston Globe columnist Bob Ryan. “The Man Upstairs may not have given him much of a right leg, but He definitely gave him a superior brain. I’m sure he can use it to earn a living.” Jack Nicklaus lamented the sport’s possible decline. “I think we would lose the game of golf forever the way we know it.” In the face of such criticism, Martin won victories in both the district and appellate courts, before the PGA appealed its case to the Supreme Court during the October 2000 term. The recently opened John Paul Stevens Papers at the Library of Congress provide new insights into the writing of the decision, reveal Stevens’s ability to craft a more inclusive majority opinion, and illustrate the Rehnquist’s court’s rulings on disability.

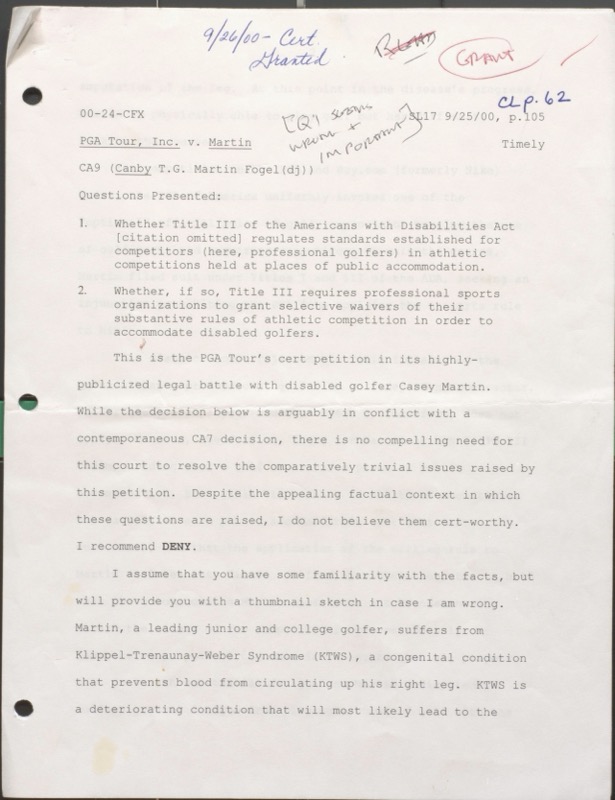

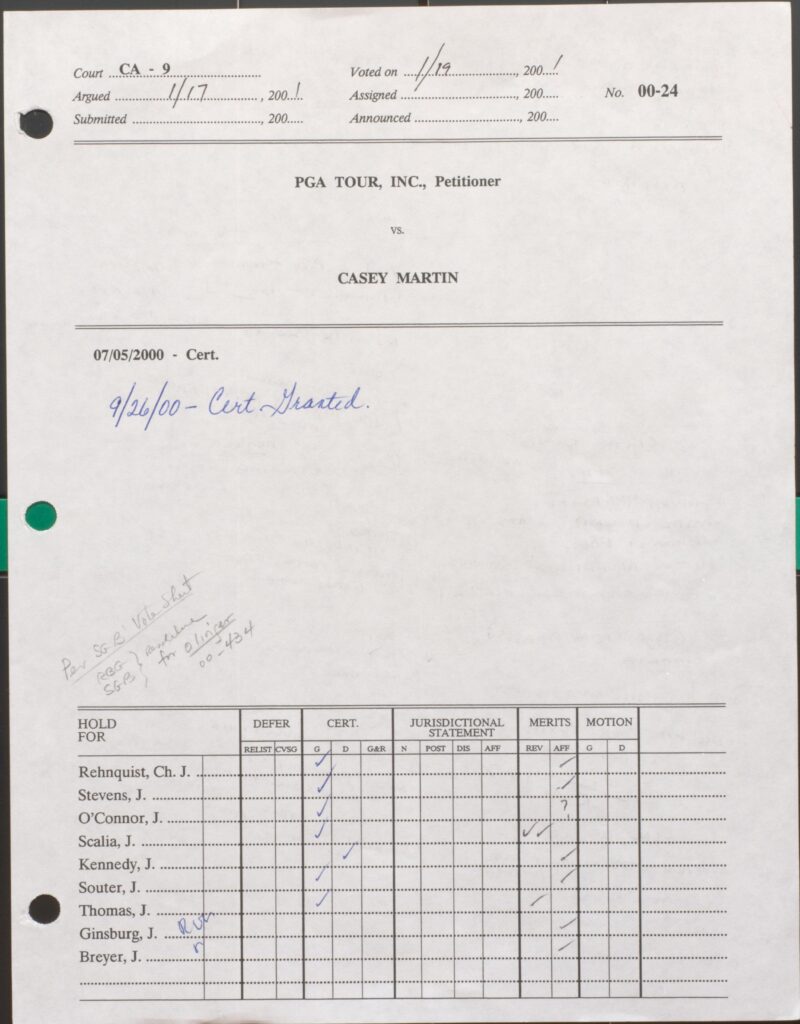

“[T]he issues presented here are not ones of national [significance] … nor are they likely to occur frequently,” Justice Stevens’s law clerk, Andrew Siegel, wrote in his review of the PGA’s cert memo to the justice. For Siegel, the issues “are not ones of national importance (even when viewed through the eyes of as large a sports fan as me), nor are they likely to recur frequently … With all due respect, I think it would be wrong to make an exception to this court’s general rules for evaluating petitions simply because the case is attractive. I strongly recommend deny.”[6]

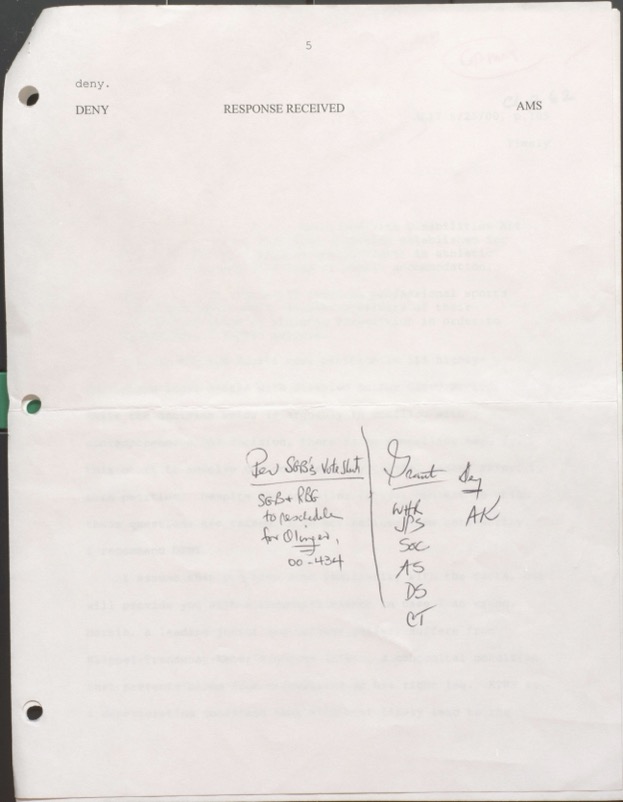

Stevens did not agree, writing “No. 1, wrong, important” across Siegel’s memo. Despite his clerk’s skepticism regarding the merits of the case, it was “the only time I remember Justice Stevens being seriously annoyed with me” Seigel recalled in 2021, and Stevens voted to grant it a hearing. According to a tally written on the back of the memo, only Justice Anthony Kennedy voted to deny, a key point in the development of the majority opinion.[7]

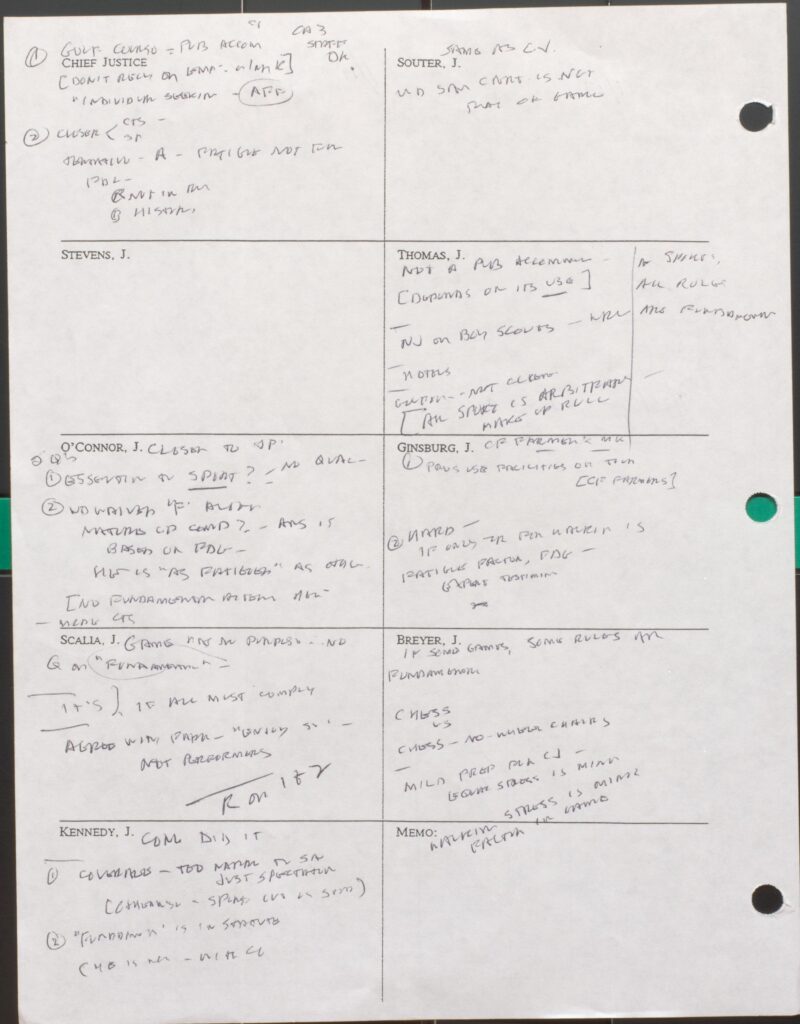

During oral argument, Scalia expressed open skepticism regarding Martin’s argument pointing to what he saw as arbitrariness in the rules that govern sport. “All sports rules are silly rules, aren’t they?” he asked Martin’s attorney, a point mirrored in the justices’ own sharply worded dissent. “But rules are rules. They are (as in all games) entirely arbitrary and there is no basis on which anyone … can pronounce one or another of them to be ‘nonessential’ if the rulemakers … deems it to be essential.”[8]

Stevens too signaled one of the main tenets of his majority opinion when he commented to the PGA’s attorney, “The thing that puzzles me … is how it can be a fundamental rule that does not apply in the qualifying events.” Unlike Scalia, Stevens was an avid golfer, and did not see the rule as arbitrary, but while acknowledging that the game changed greatly over the years – from course design to technological advances in equipment to alterations in the laws governing the game – he argued the rules ensured “the essential aspect” of the sport.[9] On this point, Scalia also disagreed. He expressed skepticism that any such “Platonic golf” existed and found the questions at the center of the case “incredibly difficult and incredibly silly.”

At conference, the chief justice tapped Stevens to write the majority opinion, demonstrating the interplay between justices on the Rehnquist Court and the ways in which these interactions shaped opinions.

After circulating his first draft, Stevens won over Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, She had expressed reservations about the accommodation fundamentally altering the game, as indicated in Steven’s conference notes and in Ginsburg’s correspondence with the justice. “Your opinion persuades me that for rare individuals like Casey Martin, the cart is a necessary and reasonable accommodation that will not ‘fundamentally alter’ the tournament,” Ginsburg wrote.[10]

Anthony Kennedy, however, remained skeptical, initially joining part of the opinion and concurring in another portion. In his letter to Stevens following the circulation of the majority opinion’s first draft, Kennedy articulated several reservations. First, he thought Stevens’s rejection of the PGA’s textual point which argued that players were not clients or customers, but employees went too far. While Kennedy agreed, he believed by raising the point, Stevens was taking the opinion into territory that “would have implications for the different, quite important issue about whether independent contractors are covered under Title III.” [11]

The justice also held reservations regarding the walking rule. “At conference I expressed some initial agreement with you on that point, but then thought there was some consensus in the majority that this might lead us into a morass involving head starts for runners etc,” Kennedy recalled. “If the suggestion is that his own exhaustion is part of the mix in determining whether there is an alteration of the game, it seems we risk mixing apples and oranges.”[12] A point, Scalia focused on in his eventual dissent: “One can envision the parents of a Little League player with attention deficit disorder trying to convince a judge that their son’s disability makes it at least 25% more difficult to hit a pitched ball.”[13]

In his drafted concurrence, written and revised several times as he and Stevens corresponded, Kennedy argued the ruling conflated the two questions at the heart of the matter: whether the cart was a “reasonable accommodation” and if its use by Martin fundamentally altered the game. Kennedy believed the opinion’s requirement of an “individualized inquiry” weakened its “solid objectivity.” Kennedy accepted the idea that some rules were peripheral and others essential, but that by utilizing an individualized inquiry, to determine if a peripheral rule was fundamental created an “artificial construct of a second tier of rules for every game” and that imposing such a structure placed an “obligation on a place of public accommodation not envisioned by Congress.” After all, the PGA could not claim expertise on disability, but rather only on whether or not a rule was integral to the sport. Kennedy found the individualized assessment both confusing and unnecessary.[14]

Finally, in their correspondence, Kennedy also wondered about a parallel case in the Seventh Circuit, Olinger v. the United States Golf Association (USGA). In that case, Ford Olinger, also a professional golfer had appealed to the USGA for use of a cart in the organization’s annual U.S. Open tournament due to his bilateral avascular necrosis, which painfully impaired his ability to walk. The Court of Appeals ruled against Olinger, but did not consider the specifics of his disability or as Siegel summarized in his review of the case, ruled abstractly, “without any reference to the particular physical characteristics of the plaintiff.”[15] Martin’s case came via the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals which had upheld an earlier district court decision. They found the accommodation reasonable and as such did not fundamentally alter the game. Considering that the two circuits broke in two different directions, Kennedy questioned the wisdom of deferring to the district court’s findings. “[D]oes the result become dependent on which case we hear?” [16]

Stevens responded immediately, first noting that while the textual argument was not “strictly necessary,” he anticipated Scalia’s dissent acknowledging it was a point “that Nino would normally find persuasive, and therefore the response is an additional hurdle that the dissent must overcome.” Still, Stevens promised to modify the language to make it clear, the Court was not ruling on the issue.[17]

Next, he addressed the walking rule. The PGA argued that its main objection to the cart was that walking caused fatigue, an issue that all players must endure. However, due to his condition, Martin, even with a cart, endured greater levels of tiredness than his competitors. Stevens did not want to dismiss the rule all together. He agreed with the testimonies of Jack Nicklaus and others emphasizing the role exhaustion played in competition. Stevens’s opinion recognized the walking rule’s legitimacy such that “(a) in some cases a cart can lessen fatigue, and (b) fatigue can affect the outcome” but weighted that with the fact that Martin’s disability meant the rule was extraneous in this regard. The walking rule wasn’t illegitimate or superfluous on its face, just in the case of Martin and the ADA.[18]

Third, Stevens dismissed concerns about giving runners head starts in races. One did not need a head start to participate in a race. “Moreover, surely the length of each race is fundamental in a track meet just as shot making is fundamental in golf,” Stevens added. The walking rule lacked the same level of importance as requiring all competitors to tee off from the same tees.[19] In the final opinion, Stevens expanded on this point in regard to golf and Martin’s argument writing that “golf is a game in which it is impossible to guarantee that all competitors will play under exactly the same conditions or that an individual’s ability will be the sold determinant of the outcome.”[20]

As both justices redrafted their opinions, they reengaged in their debate in April wherein Kennedy began to signal a compromise might be reached. “I have tried to modify my approach as much as seems possible consistent with my views,” he wrote. Stevens’s interpretation of the fundamental alteration provision still nagged at him, but he also noted that if Stevens could abide his suggestions, “It might be possible for me to concur separately while joining your opinion in full, or perhaps to withdraw my separate writing.”[21] Stevens responded the next day offering to replace an existing footnote (at the time footnote 35) regarding the fundamental alteration.[22]

Kennedy accepted this approach, “Would you consider this footnote – if a footnote it must be – modifying the one you propose?” Kennedy also requested that Stevens strike the first two sentences of the draft opinion’s final paragraph. Stevens’s early drafts provided a more critical appraisal of the PGA’s methods. “The congressional findings that are part of the ADA indicate that discrimination against persons with disabilities is often the product of uninformed prejudice rather than accurate information. While we do not doubt petitioner’s good-faith belief than an examination of Martin’s medical records would have been unnecessary because it viewed the walking rule as fundamental and not subject to waiver, petitioner’s refusal to consider Martin’s request in light of his circumstances is precisely the type of response that Congress intended to prohibit.” Kennedy found this analysis “not quite fair.” The PGA never disputed Martin’s disability or its severity. A deletion of these two sentences, Kennedy wrote, would allow for him to join the opinion, withdrawing his concurrence. “I would even accept the ignominy of having my thoughts in a footnote.”[23]

Perhaps sensing the chance to resolve the debate, Stevens called Kennedy and the two completed their negotiation over the phone. Stevens struck the first two sentences of the original final paragraph and revised the footnote that situated the analysis between three essential questions “whether the requested modification is ‘reasonable,’ whether it is ‘necessary’ for the disabled individual and whether it would ‘fundamentally alter the nature of’ the competition.” With no priority between the three, which needed to be satisfied first would vary case by case. “In routine cases, the fundamental alteration inquiry may bend with the question whether a rule is essential. Alternatively, the specifics of the claimed disability might be examined within the context of what is a reasonable or necessary modification.” Since the PGA already acknowledged Martin’s request was reasonable and had pinned its argument on the fundamental alteration provision, “we have no occasion to consider the alternatives in this case.”[24] The revision satisfied Kennedy, and by extension the chief justice who had signed on to his initial concurrence. “You have at least a birdie, maybe even an eagle,” Kenney quipped.[25]

Announced on May 29, 2001, many observers hailed it. Newspapers in Salt Lake, Pittsburgh, Columbus, and Atlanta, for example, celebrated the decision. “Does it matter how a baseball pitcher walks to the mound if he can pitch a 90 mph fastball once he gets there. Of course not. Neither should it matter how Martin gets to the tee if he can hit the ball once he arrives.”[26]

All noted the narrowness of the decision. Players suffering from bad backs would not be able to appeal for carts, any claimed disability had to fall under the ADA structure.[27] Critics, like the Post’s Sally Jenkins did not agree. “Where is it written that to play a sport at the most elite level is a constitutional right? Until, yesterday, nowhere.” Jenkins continued arguing the decision left all of sports “vulnerable to legal intervention anytime someone feels left out.”[28] While Jenkins saw wisdom in Scalia’s dissent, others, such as the editorial board of the Atlanta Journal and Constitution believed it to be indicative of misplaced skepticism regarding the ADA. “All the ADA sets out to do is allow the estimated 33 million Americans with severe disabilities to lead normal productive lives.”[29]

Over two decades later, Jenkin’s nightmare scenario remains just that, a figment of the imagination. Only one other player used the Martin decision to request a cart, John Daly at the British Open in 2019. Nor have sports been inundated with legal challenges. Yet one can imagine a world in which the Court releases this opinion today only to be greeted by chants of “woke mind virus,” though admittedly under the Court’s current construction, attitudes toward the ADA probably resemble those of Anton Scalia’s dissent more than Stevens’s majority opinion. Ironically, the Court’s apparent eagerness to hear the case, stemmed in part from what Siegal described as its “apolitical” nature, particularly after the Bush v. Gore debacle. Yet for some observers, this decision along with Bush v. Gore caused at least one letter writer to express dismay over the Court’s direction. “After the presidential decision, and now this, I am losing confidence in the Supreme Court,” one correspondent to the court opined.[30] Moreover, in today’s political climate, one could argue, nothing is apolitical. The PGA’s recent merger with LIV stands as another, morally ambiguous decision by the organization, that has drawn sharp cultural criticism and raised troubling questions for those who believe in the importance of the purity of the game.

Still, the case brought the disability to the fore and forced people to really think about the issue in American life. The reality remains that people with disabilities face more barriers to access than most other citizens, and when one adds race, gender, and sexuality into the equation even more so- and the Martin decision is an acknowledgement, that disability is contextual and relational. Too often, individuals are defined by their disability, by what people believe they can’t do.[31] “[D]isability is relational, so that ‘how disability is lived’ is also a matter of how nondisabled people constrain the disabled and construct the category of disability and are themselves made into who they are,” historian Nate Holdren wrote recently.

In PGA v. Martin, Stevens conducted this analysis, noting that if fatigue is the reason for the walk rule, Martin’s condition easily outweighed others in this category, Martin was enduring the fatigue people thought he was skirting by using the cart. Stevens saw beyond the disability, and as a golfer thought deeply about the intersection of professional competition and disability. The ADA turned thirty in 2020, and the disability rights movement, though decades in the making, only began to prick the public consciousness in the late 1970s when activists demanded access and equality, more challenges will come and while the Martin case is limited in its scope, it remains a point of departure for future decisions on the issue. Martin forced the court and Americans, to really grapple with disability as a concept, we should not be surprised that in retrospect, some folks took positions that today seem, short sighted.

As they discussed Martin’s case, Stevens signed on to Justice Stephen Breyer’s dissent in Board of Trustees of University of Alabama v. Garrett, in which chief justice Rehnquist’s majority opinion argued that the ADA did not enable state employees to recoup financial damages based on the laws Title I provision which barred “discrimination against a qualified individual with a disability because of that disability… in regard to… terms, conditions, and privileges of employment.” Rehnquist and the majority of the Court believed the Eleventh Amendment trumped the ADA. In this way, and others, disability law remains in flux and still developing.

Perhaps, the golf blog Lying Four states it best when noting that despite the array of barriers that still limit folks with disabilities, “in both society and in golf, lies a disbelief that anyone who looks or behaves differently would dare walk through the clubhouse door. And not even the Supreme Court could strike that down.”

[1] David Cathey to John Paul Stevens, 2001, Box 848, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[2] Howard J. Mindell to John Paul Stevens, May 30, 2001, Box 848, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[3] Sally Jenkins, “A Good Walk is Truly Spoiled,” Washington Post, May 30, 2001, box 848, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[4] Thomas Bonk, “Golf: Martin’s Years Might End in a Half Swing,” Los Angeles Times, May 24, 2001, Box 848, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress; “Twenty Years Later, Casey Martin Still Stands Alone,” Lying Four, May 28, 2021, accessed November 2, 2023, https://www.lyingfour.com/conversations-blog/2021/5/27/gmfy37k9owf5ejxmy6z0o7b4d6gbe9.

[5] Golf courses are formally recognized under the Americans with Disabilities Act as public accommodations.

[6] AMS, Cert Memo: PGA Tour, Inc. v Martin, September 25, 2000, Box 848, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

[7] AMS, Cert Memo: PGA Tour, Inc. v Martin, September 25, 2000, Box 848, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

[8] PGA Tour, Inc. v. Martin, 532 U.S. 661 (2001).

[9] PGA Tour, Inc. v. Martin, 532 U.S. 661 (2001).

[10] John Paul Stevens, conference notes, PGA Tour, Inc. v Martin, January 17, 2001, Box 847, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress; Ruth Bader Ginsburg to John Paul Stevens, April 8, 2001, Box 848, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

[11] Anthony Kennedy to John Paul Stevens, March 9, 2001, Box 847, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

[12] Anthony Kennedy to John Paul Stevens, March 9, 2001, Box 847, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

[13] PGA Tour, Inc. v. Martin, 532 U.S. 661 (2001)

[14] Anthony Kennedy, 3rd draft concurrence, PGA Tour, Inc. v Martin, March 15, 2001, Box 847, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[15] AMS, Cert Memo: PGA Tour, Inc. v Martin, September 25, 2000, Box 848, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[16] AMS, Cert Memo: PGA Tour, Inc. v Martin, September 25, 2000, Box 848, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[17] John Paul Stevens to Anthony Kennedy, March 12, 2001, Box 847, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[18] John Paul Stevens to Anthony Kennedy, March 12, 2001, Box 847, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[19] John Paul Stevens to Anthony Kennedy, March 12, 2001, Box 847, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[20] PGA Tour, Inc. v. Martin, 532 U.S. 661 (2001).

[21] Anthony Kennedy to John Paul Stevens, April 18, 2001, Box 847, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[22] John Paul Stevens to Anthony Kennedy, April 19, 2001, Box 847, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[23] Anthony Kennedy to John Paul Stevens, April 20, 2001, Box 847, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[24] John Paul Stevens to Anthony Kennedy, April 20, 2001, Box 847, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[25] Anthony Kennedy to John Paul Stevens, April 20, 2001, Box 847, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress; Anthony Kennedy to John Paul Stevens, April 23, 2001, box 847?, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

[26] Disabled Given a Fair Swing at PGA,” Atlanta Journal and Constitution, May 31, 2001, Box 848, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[27] “Not in the Rough Supreme Court Takes a Good Swing in the Golfer Case,” Pittsburgh Post Gazette, June 1, 2001; “Ticket to Ride,” Columbus Dispatch, June 2, 2001; “Par for the Court,” The Salt Lake Tribune, June 1, 200; “Disabled Given a Fair Swing at PGA,” Atlanta Journal and Constitution, May 31, 2001, Box 848, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[28] Sally Jenkins, “A Good Walk is Truly Spoiled,” Washington Post, May 30, 2001, Box 848, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[29] Disabled Given a Fair Swing at PGA,” Atlanta Journal and Constitution, May 31, 2001, Box 848, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[30] Howard J. Mindell to John Paul Stevens, May 30, 2001, Box 848, John Paul Stevens Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

[31] Kim E. Nielsen, A Disability History of the United States (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2017), xiv-xv.