In my office, right by my desk, I have a “go-to shelf.” This is a small collection of books that I refer to constantly. Three volumes of Jim’s work are on it: the two volumes of The Mansfield Manuscripts and his book Trial by Jury: The Seventh Amendment and Anglo-American Special Juries.[1]

Jim’s written work, which includes far more than those volumes, has had an immense influence. In this post, I’ll discuss how his research into the eighteenth-century jury has revolutionized our understanding of the institution and holds powerful implications for interpretation of the Seventh Amendment.

But Jim’s influence has gone well beyond his written work, potent as that is. Jim has been a wonderful guide in studying juries. My specialty is the American jury, and Jim has deep knowledge of American as well as English practice. His guidance reflects his varied interests, including his sense of humor and love of collecting books. He told me about The Comic Blackstone, published by Punch in 1844, with its send-up of Blackstone’s effusive chapter about the civil jury.[2] The Comic Blackstone includes gems such as: “It is difficult to get the British bosom into a sufficiently tranquil state to discuss this great subject; for every Englishman’s heart will begin bounding like a tremendous bonse [drum], at the bare mention of trial by jury.”[3] And: “It would be right down blasphemy to doubt the integrity of a British jury . . . but we have nevertheless heard of that great bulwark of our liberties tossing up [flipping a coin] occasionally, when a verdict could not be otherwise agreed upon.”[4] The Comic Blackstone went through many English editions, with illustrations by George Cruikshank, and was also popular in American editions.

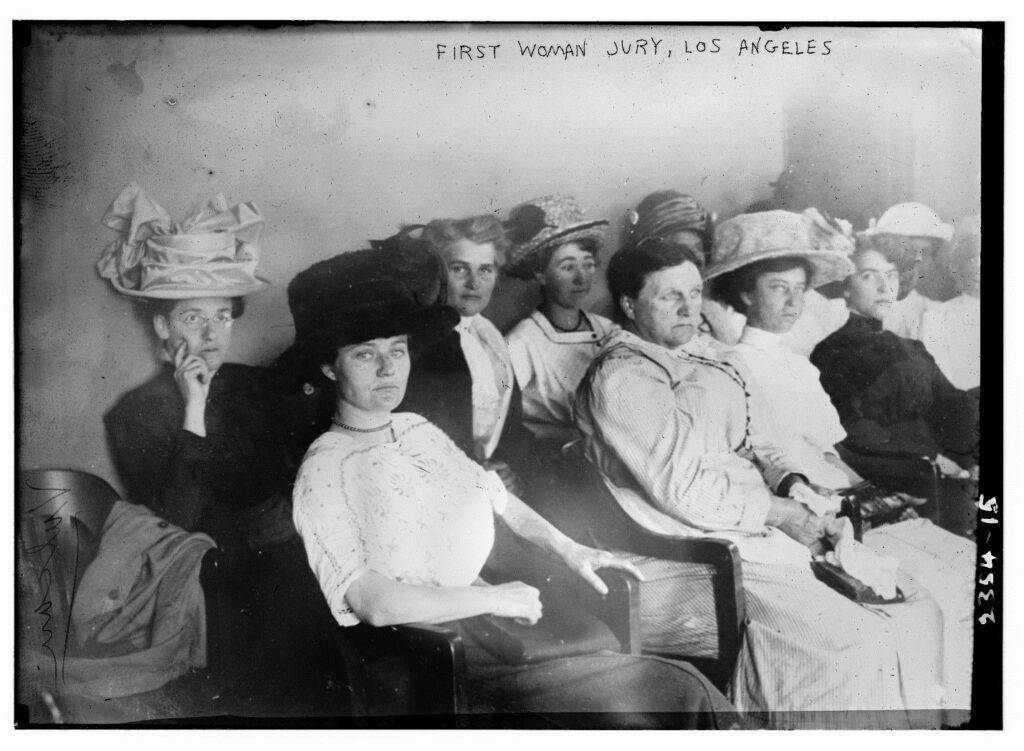

Jim believes that images are a powerful supplement to words, and he has taken extraordinary pains to find them. He described to me searching for the marvelous illustrations for his book Trial by Jury in the days before everything was digitized and online. Combing through materials in the Library of Congress, he found a priceless photo of an all-female jury in Los Angeles in 1911. The hats are a delight. That jury acquitted the publisher of the Watts News of printing obscene and indecent language. The publisher’s defense was that he was quoting the words of a Watts city councilman. As one juror put it, “Our verdict did not mean that we approved of such language. It meant that we believed the defendant was honest in his endeavor to aid the public when he printed the article.”[5] For that jury, a deputy constable summoned 36 women and no men. Whoever wanted to impanel only women was disappointed if the person expected female jurors to convict because they disapproved of bad language.

Jim’s insights, including The Comic Blackstone and the photo of the all-female jury, appear in my book The Jury: A Very Short Introduction.[6]

Jim’s work has transformed our understanding of the eighteenth-century jury. In the United States, lawyers and judges tend to think that jury trial was always the way it is here now, with the advocates left to go at it in front of the jury, and a largely silent judge until it comes to the judicial instructions, when the judge drops a tedious load of legal terms on the jury and gives no help at all on the facts. Sometimes, as in patent infringement cases or complicated commercial cases, the jury is completely baffled. No wonder parties settle at such great rates and avoid adjudication altogether, or arbitrate. Judges have privately expressed their doubts to me about this system. (Of course, they would never do so in public.) One federal district judge told me that the use of civil juries in patent cases was “insane.” A federal circuit judge used a somewhat different word: He said it was “crazy.”

What Jim has shown us so beautifully in his work is that jury practice was not always this way. It was not like this in late eighteenth-century England. And therefore, it need not be this way under the Seventh Amendment and its historical test. Under the historical test, courts look to English practice as of 1791, the time the Seventh Amendment was ratified, to determine whether a jury trial is required.[7]

English judges had wide power to comment on evidence and to, in effect, direct the jury. As Jim has written, although a jury in the eighteenth century was not legally obliged to follow a judge’s direction, “trial judges did frequently direct juries to find for one party or the other, and juries ordinarily complied.”[8] Jim recounts an exchange between Lord Mansfield and James Boswell. Boswell asked him whether juries always took his direction, and Mansfield answered, “Yes except in political cases where they do not at all keep themselves to right and wrong.”[9] Jim has explored in detail Mansfield’s efforts to control juries in seditious libel cases.[10] I’ve quoted Jim’s findings about judicial instructions and comment on evidence repeatedly in my work.

U.S. judges have of course lost the power to comment on evidence, a loss that John Henry Wigmore wrote “has done more than any other one thing to impair the general efficiency of jury trial as an instrument of justice.”[11] I and others have traced the loss of this power in the United States.[12]

Some of the more striking examples of judicial instructions that Jim has revealed appear in cases of criminal conversation, or crim con. These were actions by a husband against his wife’s lover. In 1788, just days after he assumed the position of Chief Justice of King’s Bench, Lord Kenyon told a jury:

[A]lthough this is only the third day I have unworthily filled this place, this is the second cause of this kind that has come before me. – To you, juries, the guardianship and protection of families is committed; – it is your duty to teach men who thus transgress the laws of God and of society, that it is in their interest, to restrain their passions, and to regulate them according to rules of morality and decency.[13]

Judicial control of juries did not end with instructions. Sometimes, despite their powers to comment on evidence, a judge was still unhappy with the verdict. Jim has examined Mansfield’s and other judges’ use of new trial, especially on the grounds of insufficient evidence.[14]

Jim has explained that not only did late eighteenth-century judges control ordinary juries, they could bypass them altogether if the judges thought cases were too complicated. In both his book Trial by Jury and a law review article, Jim shows us the methods judges used.[15] One was to substitute an expert jury for an ordinary one. Paul Halliday and Dick Helmholz have already mentioned Mansfield’s and others’ use of special juries of merchants and of other kinds.

But judges had other options. One was to refer a case to arbitration by a knowledgeable expert. Jim describes a 1799 case in which Lord Eldon, when he was Chief Justice of Common Pleas, “took an extraordinary degree of pains” to coax the defendant to refer to arbitration a case involving a conveyancer’s bill. Eldon explained that both he and a jury would be completely baffled, and that the case would be better off in the hands of someone “who was acquainted with that branch of the profession.” The defendant gave in, and the case was referred.[16]

Judges also accepted demurrers to the evidence, which in effect took a case from a jury and put it in the hands of the judges. In 1791, famed advocate Thomas Erskine explained his use of demurrer:

I respect the Trial by Jury, because it is a part of the Constitution of the country, and therefore entitled to my respect, but the same Constitution which instituted the Trial by Jury instituted also a demurrer to evidence, and therefore both of these, as parts of one harmonious whole, are equally respectable.[17]

Judges could take a jury verdict subject to a “case stated,” which reserved a legal question for the full court.[18] That practice has influenced the U.S. Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Seventh Amendment’s Re-examination Clause. In Baltimore and Carolina Line v. Redman in 1935, the Court permitted the practice of judgment notwithstanding the verdict if the trial court explicitly reserved a legal question.[19] In doing so, the Court referred to the English practice of judges reserving questions of law.

Jim explains that judges had still further possibilities, including having experts on the bench with them during the trial to give advice as needed. And he shows a fluid relationship between Chancery and the common law courts in determining facts.[20]

Considering all these methods of dealing with complex cases that either bypassed or greatly modified jury trial, Jim concluded that a “complexity exception” to the Seventh Amendment would be legitimate under the historical test.[21] That question had come up in a 1980 case in the Third Circuit, In re Japanese Electronic Products Litigation, with elaborate briefs—and subsequent publications—by Morris Arnold and Patrick Devlin. In the end, the Third Circuit avoided the question and rested its decision on due process grounds.[22] But Jim’s work has far outshone anything else on the issue. He has demonstrated that we need not be prisoners of a supposed requirement of ordinary juries under the Seventh Amendment.

I’d like to say a word about Jim’s sources. We all know about Jim’s mining the Mansfield manuscripts and other judges’ notes for insight. Indeed, we have a whole discussion dedicated to Jim’s use of those sources. But many of the examples I’ve quoted do not come from judges’ notes or manuscripts. Once I was talking with Jim about the difficulty of getting accurate information about judges’ charges to juries. I was expecting him to discuss judges’ notes. But his response surprised me: “Newspapers!” Jim’s use of newspapers, particularly The Times of London, has been a revelation. In painstakingly examining newspaper accounts, he has found many valuable examples of judges’ charges, practices, and cases that were not reported.

Jim has greatly deepened our understanding of eighteenth-century English jury practice. This ought to provoke a revolution in our understanding of the Seventh Amendment and modern American jury practice. Besides his transformational work, Jim is also a personal inspiration, with unbounded energy, curiosity, graciousness, and always a twinkle in his eye. We who study juries stand on the shoulders of a giant.

[1] James Oldham, The Mansfield Manuscripts and the Growth of English Law in the Eighteenth Century (University of North Carolina Press, 1992); James Oldham, English Common Law in the Age of Mansfield (University of North Carolina Press, 2004).

[2] Gilbert Abbott à Beckett, The Comic Blackstone (London: Punch Office, 1844); William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England (1768) 3: 349-85.

[3] Beckett, Comic Blackstone, 274.

[4] Ibid., 275.

[5] “Women Acquit Man Accused of Printing Obscene Matter,” The Tacoma Times, November 3, 1911, at 7.

[6] Renée Lettow Lerner, The Jury: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2023).

[7] Dimick v. Schiedt, 293 U.S. 474, 476 (1935).

[8] James Oldham, English Common Law in the Age of Mansfield 68 (2004). See also John H. Langbein, “Historical Foundations of the Law of Evidence: A View from the Ryder Sources,” Columbia Law Review 96 (1996): 1168, 1191-93.

[9] Oldham, Mansfield Manuscripts, 1: 206 n. 44.

[10] Oldham, Mansfield Manuscripts, 2: 775-808.

[11] John H. Wigmore, A Treatise on the Anglo-American System of Evidence in Trials at Common Law, 2d ed. 5: 557, § 2551 (1923).

[12] Renée Lettow Lerner, “How the Creation of Appellate Courts in England and the United States Limited Judicial Comment on Evidence to the Jury,” Journal of the Legal Profession 40 (2016): 215-270; Renée Lettow Lerner, “The Transformation of the American Civil Trial: The Silent Judge,” William and Mary Law Review 42 (2000): 195-264 (2000); Kenneth A. Krasity, “The Role of the Judge in Jury Trials: The Elimination of Judicial Evaluation of Fact in American State Courts from 1795 to 1913,” University of Detroit Law Review 62 (1985): 595-632.

[13] James Oldham, “Only Eleven Shillings: Abusing Public Justice in England in the Late Eighteenth Century,” Green Bag 2d 15 (2012): 175, 187.

[14] Oldham, Mansfield Manuscripts, 1: 89-91, 157-160.

[15] Oldham, Trial by Jury, 10-24; James Oldham, “On the Question of a Complexity Exception to the Seventh Amendment Guarantee of Trial by Jury,” Ohio State Law Journal 71 (2010): 1031-1053.

[16] Ibid., 1036.

[17] Ibid., 1038.

[18] Ibid., at 1040.

[19] 295 U.S. 654, 658-661 (1935).

[20] Oldham, “Complexity Exception,” 1033-35, 1040.

[21] Oldham, Trial by Jury, 24; Oldham, “Complexity Exception,” 1053.

[22] 631 F.2d 1069, 1089-1090 (3d Cir. 1980).