Cordelia Beattie‘s article, “Married Women’s Wills: Probate, Property, and Piety in Later Medieval England,” appears in the latest issue of Law and History Review. Below, she explains some of her main insights into married women’s property in medieval England.

The Married Women’s Property Act of 1882, which gave wives the right to own their own property, is often viewed as a key victory in women’s struggle to be counted as full citizens in Britain.[1] The point at which married women had lost this right is roughly dated to the thirteenth century,[2] when the new common law doctrine of coverture made husbands the legal guardians of their wives, who could not own any property separately during the marriage. The doctrine was later exported to Britain’s colonies and its evolution is still being traced.[3] Coverture was never abolished outright by legislation but was chipped away slowly. As recently as 1981, it had to be declared in a civil case that the legal fiction of husband and wife as one person no longer existed, even under common law.[4] However, the doctrine’s impact is felt even today. In 2016, the BBC interviewed women who had experienced discrimination, such as having their bank accounts put into their husbands’ names on marriage in the 1960s and 1970s. One widow reported finding it hard to get a credit card in her own name as she had not built up a credit rating of her own as a result.[5]

For medievalists, attempts to find limitations on the practice of coverture led some to overemphasise the custom which operated in some English towns of allowing married women to trade as if single (as femme sole).[6] For early modernists, attention has been paid to marriage settlements which allowed women or their families to keep property out of the hands of the husbands.[7] Indeed, Richard Helmholz argued that moves in this direction in the fifteenth century might explain why married women rarely made wills after c.1450.[8] The future of their property would have been dealt with in such settlements.

It has become a commonplace in recent scholarship to note that married women in late medieval England rarely made wills, usually with a reference to Helmholz’s 1993 essay on the subject.[9] However, when reading Lawrence Poos’ edition of the court book of the Deanery of Wisbech, 1458-84, I was struck by the relatively high proportion of married women’s wills amongst all those recorded (12 of 181; 6.6%).[10] This set me off on a hunt to see where else married women’s wills might survive, starting with other printed editions but moving on to archives in York, Bury St. Edmunds, Norwich and Cambridge. In some areas there was a marked, early decline in married women’s will-making. For example, in the registers of the Dean and Chapter of York, now in York Minster Library, the last married woman’s will I found dated from 1446.[11] In others, there were enough married women’s wills in the late fifteenth century for me to start to see some interesting patterns.

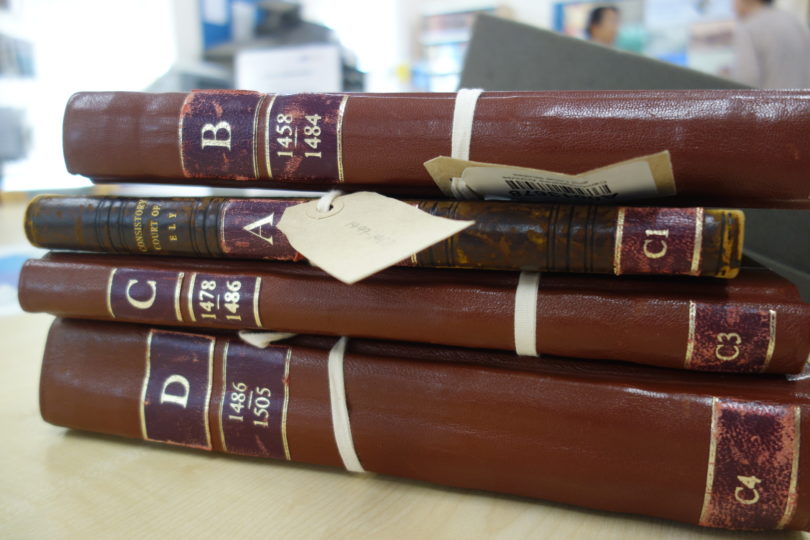

In Cambridgeshire Record Office, then in Cambridge although now in the process of moving to Ely, the court book of the Deanery of Wisbech exists as part of a series of probate registers for the diocese of Ely, from 1449 stretching into the sixteenth century. The bound manuscript volumes are labelled Liber A, B (the court book), C and D, with the titles being contemporary or near contemporary with the volumes’ compilation.[12] From examining these registers, I came to a number of conclusions. First, in this diocese there was a decline in recorded married women’s wills over the course of the fifteenth century: from 37 in Liber A (of 257; 14.4%), covering the period 1449-60, to 10 in Liber D (of 549; 1.8%), for the period 1486-1505. Second, those that were recorded by the end of the fifteenth century were more likely to be those that dealt with land or buildings. This was not the case in Liber A, where most married women’s wills were concerned only with religious offerings or small bequests of clothing and personal jewelry. Third, those married women whose wills were recorded despite having little to leave tended to have a close connection to a churchwarden or a juror in the court which probated their wills.

I also found a similar trend in court books for the Archdeaconry of Buckingham, 1483-97. In this court material, only two married women’s wills were recorded, both of which mention a tenement acquired from a previous marriage. However, there are thirty-five notes of probate pertaining to married women in the same period (of 195; 17.9%).[13] This suggests that while married women continued to make wills and have them proved in this area up to the end of the fifteenth century, their executors were unlikely to make the payment to have the wills recorded unless they concerned substantial property. Also, some of the husbands who were named as executors in the notes of probate share their names with men who were churchwardens in the same parts of Buckinghamshire, or nearby, around the same time.

Ian Forrest has recently written a very interesting study on the men who acted as local jurors in late medieval England but my own research suggests that we also need to think about their wives too.[14] The recorded wills in Wisbech, for example, suggest that wives or sisters of jurors were more likely to make wills, even when they had very few possessions to dispose of, and to have these wills recorded in the local court.

My research does not overturn the work of scholars like P.J.P. Goldberg who argued that married women’s will-making in York declined in the first half of the fifteenth century.[15] Rather, it nuances Helmholz’s England-wide argument and suggests that there was regional variation in this decline, as Helmholz himself found for the custom of legitim, the practice of a third of a testator’s goods being allocated to his or her children.[16] My work also adds another dimension to the debate about the impact of different legal jurisdictions on the property rights and legal abilities of married women. Rather than a clear victor in the battle between common law and canon law over whether married women could make wills, or a focus on equity law as a way to subvert common law, my findings suggest that we need to allow for more variability in practices. Just because common law set out a particular position, we should not assume that medieval people always followed it. Some married women had a clear sense of the property they owned and their husbands and the courts did not dispute this.

[1] E.g. the episode on “The Married Women’s Property Act” online at www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m0002196, broadcast 16 Jan. 2019 (accessed 11 Feb. 2019).

[2] See Charles Donahue Jr, “What Causes Fundamental Legal Ideas? Marital Property in England and France in the Thirteenth Century,” Michigan Law Review 78 no. 1 (1979): 59-88.

[3] E.g. see Tim Stretton and Krista J. Kesselring, eds., Married Women and the Law: Coverture in England and the Common Law World (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2013) and many of the essays in Cordelia Beattie and Matthew Frank Stevens, eds., Married Women and the Law in Premodern Northwest Europe (Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2013).

[4] J.H. Baker, An Introduction to English Legal History, 3rd ed. (London: Butterworths, 1990), p. 551, n26.

[5] Claire Bates, “Credit card sexism: The woman who couldn’t buy a moped,” BBC News Magazine, 6 July 2016, at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-36662872 (accessed 11 Feb. 2019).

[6] Cf. Marjorie K. McIntosh, “The Benefits and Drawbacks of Femme Sole Status in England, 1300-1630,” Journal of British Studies 44 (2005): 410-38; Sara M. Butler, “Femme Sole Status: A Failed Feminist Dream?,” Legal History Miscellany, 8 Feb. 2019, online at https://legalhistorymiscellany.com/2019/02/08/femme-sole-status-a-failed-feminist-dream/ (accessed 11 Feb. 2019).

[7] E.g. Amy Louise Erickson, “Common Law versus Common Practice: The Use of Marriage Settlements in Early Modern England,” Economic History Review 43, no. 1 (1990): 21-39.

[8] Richard H. Helmholz, “Married Women’s Wills in Later Medieval England,” in Wife and Widow in Medieval England, ed. Sue Sheridan Walker (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1993), 165-82.

[9] Ibid.

[10] L. R. Poos, ed., Lower Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction in Late-Medieval England: The Courts of the Dean and Chapter of Lincoln, 1336-1349, and the Deanery of Wisbech, 1458-1484, Records of Social and Economic History new series 32 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 267-592.

[11] York Minster Library, Dean and Chapter Registers, D/C Reg. 1, fo. 244 (Agnes Parke).

[12] Poos, Lower Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction, xxxviii.

[13] E.M. Elvey, ed., The Courts of the Archdeaconry of Buckingham, 1483-1523, Buckinghamshire Record Society, 19 (1975), 1-189.

[14] Ian Forrest, Trustworthy Men: How Inequality and Faith Made the Medieval Church (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018).

[15] P. J. P. Goldberg, Women, Work, and Life Cycle in a Medieval Economy: Women in York and Yorkshire c.1300-1520 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992), 264-9.

[16] Richard H. Helmholz, “Legitim in English Legal History”, University of Illinois Law Review 3 (1984): 659-74.

Cordelia Beattie is Senior Lecturer in Medieval History at the

Cordelia Beattie is Senior Lecturer in Medieval History at the