I have recently been working on late medieval and early modern petitions from England’s Court of Chancery to understand how plaintiffs and counsel were able to use emotions as part of legal strategy. Unlike common law courts, chancery was a court of conscience and cases came into the court’s jurisdiction if there was an offense against conscience, either by direct action or by omission. The court’s characteristic emphasis on conscience, and later equity, steadily evolved into a codified system by the mid-sixteenth century, but it had its roots in the early fifteenth century. While the language of conscience dominates the legal phrasing and logic of the petitions, exactly what “conscience” was and how it could be subjectively measured was a fraught matter. Conscience engages a sense of personal moral judgment but one on which a court “of conscience” had to be fit to make judgments. The oftentimes formulaic moral language of petitions is therefore obvious. However, emotional language is also present in Chancery petitions. We can understand the role emotions played in petitions by employing several methodologies, including correlating petitionary evidence with contemporary views about the relationship between morality and emotion. Moreover, we should credit petitioners, respondents and their counsel with awareness that emotions could have a role in the presentation of legal claims and of the power of emotions as a technique of persuasion.

Focusing on cases involving London merchants, I argue that sensitivity to emotional language, as well as to the motivations behind its inclusion in some chancery petitions, helps us to understand how the court could reflect emotional beliefs about conflict. Adding to the already difficult nature of uncovering emotional authenticity in legal sources is the imprecision of emotional language, which can be slippery and ambiguous, just as emotions themselves are ambiguously felt and expressed. What do “emotion words” look like? More problematically still, how do we deal with the extensive use of formulaic language in the petitions? Given the connection between words and meaning, this has a deeper impact on our research than we sometimes admit. And yet, historians wishing to access historical emotions must do something if they want to understand how petitioners and counsel were construing meaning through the words they were choosing. Formulaic language needs to be taken seriously because it potentially reveals contemporary expectations and knowledge about emotional standards. More robust approaches to formulaic language need to be developed if we wish to fully scrutinize historical sources where formulae are commonly used, particularly legal and administrative documents.

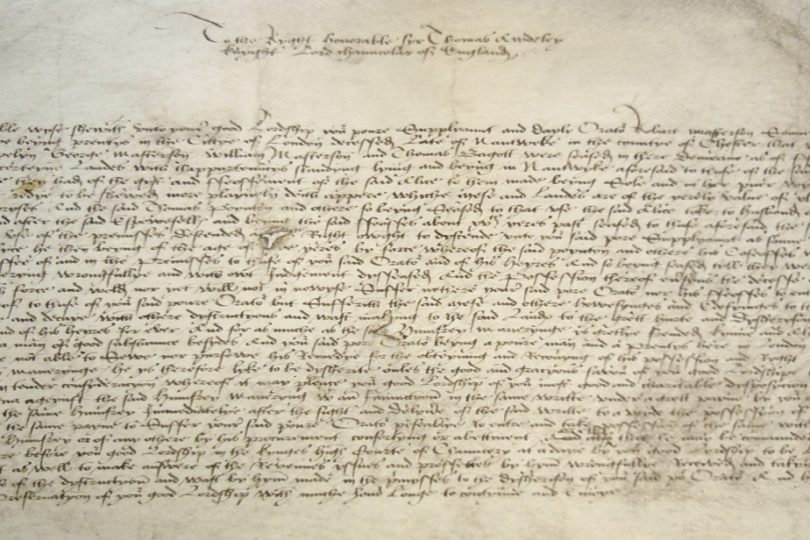

The composition of chancery sources requires careful thought because it profoundly affects the nature of the evidence to which we have access. On first inspection, chancery’s formulaic bill structure seems to be problematic for the task of understanding lived experience, and certainly understanding emotional experience. Bills followed a set structure: address, incipit, recital, problem, conclusion, supplication, consideration, request for process, examination, remedy and explicit.[1] Cordelia Beattie points out that the intention of the bill of complaint was to ensure the case was moved into chancery’s jurisdiction and not merely to tell a compelling story, important as this would later become as the case progressed.[2] Chancery’s bill structure exerted enormous institutional and customary pressure on petitions, which are often terse, a process of collaboration, and written in highly formulaic ways.

Because of Timothy Haskett’s work on bill pairs – petitions dealing with the same matter but from different petitioners – we know that chancery allowed evidence to be tailored within these required sections and that individualized evidence was permissible. Haskett’s argument helps us consider how emotional language could be incorporated into the bill within the requirements of legal formulae. Subtle language differences, as well as varying the emphasis placed on the closeness or distance of social relationships between people, highlighted the petitioner as an individual. This type of tailoring allowed cases to become more personal.[3] Petitioners brought a range of social and cultural expectations relating to behaviour into the court, and, in their language, spoke of actions and events which were driven by day-to-day, even mundane, rhythms of fear, annoyances, contested loyalties, hatreds, and sympathy. In their language choices, we see petitioners characterise apprentices as being “corrupted with giftes and pleasures,” or jurors being intimidated into feeling “drede of their lyves” after being harassed. The skill and experience of legal counsel can be seen in these modifications. We should also appreciate the degree of adaptation that could be achieved by including emotions like fear, dread, sorrow and anger, and less rarely, emotions like love and kindness. Plaintiffs, defendants and counsel made judgments that drew distinctions between actions and behaviour motivated by improper emotion and carried out in states of excessive emotion, from actions that were reasonable.

There is no doubt that chancery bills are extremely formulaic. In chancery, formulaic phrases which are consistently used include “in good conscience,” “all ryght and good conscyence,” the similar “accordyng to right equyte and good conscience,” “for love of charity,” “tender pity,” “utter undoing,” “showeth meekly” or “humbly,” “subtle and crafty,” and third person representations in the form of “your said beseecher,” “your poor orator/oratrice” and “poor supplicant.” The formulaic term “malice” is also common and is one I explore in depth in my LHR article. How historians use standardized language to understand emotions is therefore vital. For some historians, formulaic expressions silence the voice of the individual and should be removed to better hear the petitioner or witness. Garthine Walker removes “repetitive and formulaic expressions” to enhance the individual’s voice, and Laura Gowing has spoken of the “disrupting and often homogenizing process of legal record-keeping.”[4] Flashes of emotional evidence can appear to enliven the flow of expected and formulaic legal evidence, although here we encounter the problem of who was exerting control over the written petitions. These problems, and problems arising from formulaic terms, are real but they do not automatically make chancery cases unusable as evidence of emotional values.

The dismissal of formulaic language may also too readily overlook one of the most distinctive features of legal sources. Anthropologists and linguists have carried out extensive work analysing the function of formulaic language, arguing that such phrases reveal, amongst other things, “structures of expectation governing the production of discourse.”[5] This expectation of a particular outcome, or the desire for that outcome, is not merely bureaucratic or neutral. In chancery, formulas about malice, humility, poverty, and love of charity, speak to a feeling of emotional expectation about the court’s role in settling discord. That formulaic discourse is not itself emotionally neutral is one we would do well to observe. Recent work has argued that formulaic language is an important route to studying the function of emotions as it reveals social conditions attached to particular emotional beliefs. The many different cultures, periods, geographical locations, and genres in which we find formulaic language suggests formulaic idioms are a commonplace of all societies.[6]

There is a valuable area to be explored between the practice of making bills conform to a particular legal discourse, and dismissing these phrases as formulaic. While formulaic passages are not individualized in the way some language choices can be, they are still heavily implicated in a particular way of seeing the world. In the long term, reinserting formulas into our reading of documents will help to inform the investigation of emotion and the relationship between feeling and language.[7] Simply put, we should avoid dismissively using words like “mere” or “just” when we talk about formulaic language, as well as when we talk about emotional norms. Ignoring formulae privileges the idea that spontaneous language and spontaneous emotions are real and that other forms of emotions are disingenuous. The careful and thoughtful examination of formulas should be fully incorporated into our approach to a great many historical sources, including legal ones.

[1] Timothy S. Haskett, “The Presentation of Cases in Medieval Chancery Bills,” in Legal History in the Making: Proceedings of the Ninth British Legal History Conference, ed. William M. Gordon (London: Hambledon Press, 1991), 11-28. Gwilym Dodd identifies a slightly different set of epistolary principles in petitions to the crown. “Writing Wrongs: The Drafting of Supplications to the Crown in Later Fourteenth-Century England,” Medium Aevum 80, no. 2 (2011), 224.

[2] Cordelia Beattie, “Your Oratrice: Women’s Petitions to the Late Medieval Court of Chancery,” in Women, Agency and the Law, 1300—1700, eds. Bronach Kane and Fiona Williams (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2013), 22.

[3] Haskett, “Presentation of Cases,” 14-17.

[4] Garthine Walker, “Rereading Rape and Sexual Violence in Early Modern England,” Gender and History 10 no. 1 (December 1998), 20, n.4; Laura Gowing, Domestic Dangers: Women, Words, and Sex in Early Modern London (Oxford: Clarendon, 1996), p. 9, pp. 45-7.

[5] James M. Wilce, Language and Emotion (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2009), p. 47. Similar work on legal formulas in letter-writing has also shown the powerful role formulas have in creating meaning. James Daybell, ed., Early Modern Women’s Letter Writing, 1450-1700 (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001).

[6] This includes medieval historians, such as Barbara Rosenwein who have analyzed commonplace language in medieval records, as well as Hellenistic scholars such as Chrysi Kotsifou, “Emotions and Papyri: Insights into the Theatre of Human Experience in Antiquity”, in Unveiling Emotions Sources and Methods for the Study of Emotions in the Greek World, ed. Angelos Chaniotis (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2012), pp. 39-90.

[7] Frances E. Dolan, True Relations: Reading, Literature, and Evidence in Seventeenth-Century England (Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013).

Merridee L. Bailey is the

Merridee L. Bailey is the