In Fall 1998, I enrolled in Bill Novak’s graduate seminar, and thus from the first moment of my graduate training in history I was encouraged to start thinking about the ideas about state capacity and state power so elegantly developed in New Democracy.[1] Bill encouraged us to flip through the pages of the Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences and the New Encyclopedia of Social Reform for paper topics, and in one class asked us to collectively write on the board all of the government functions we could think of.

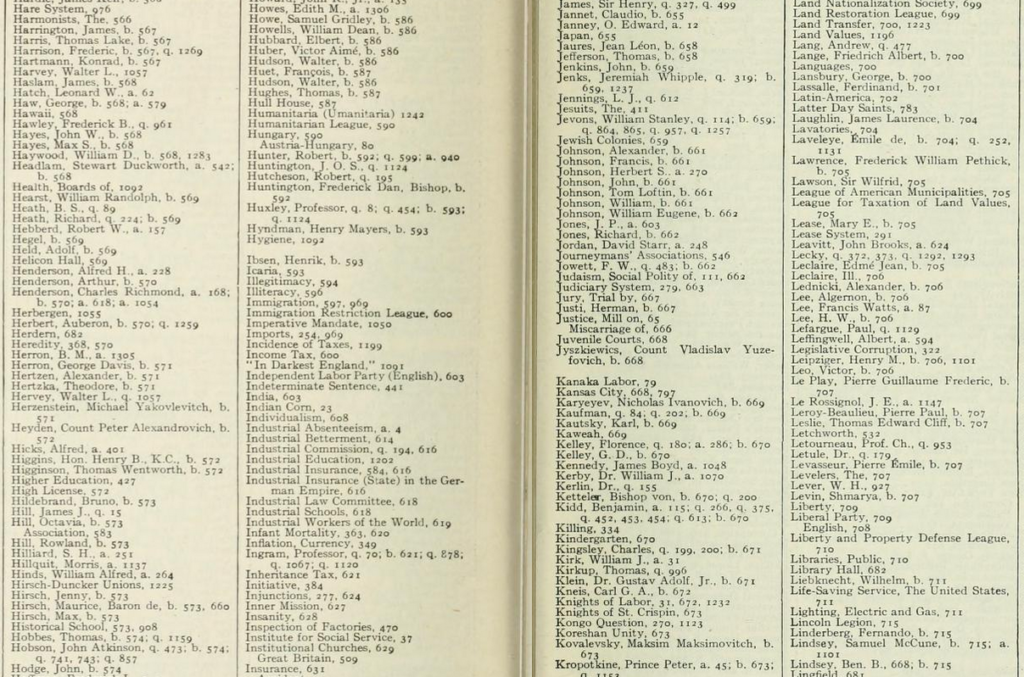

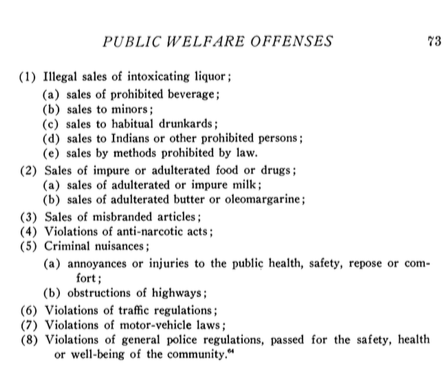

There are several things I really admire about the contributions of New Democracy.. First, the book looks at what the state actually does—not its essence or its vibe, but the actual tasks it performs. We see in New Democracy, as in The People’s Welfare, a host of lists that work to illustrate the dazzling array of topics that were regulated by law in service of the public interest.

Once Novak establishes the scope of what the state was actually doing in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, he focuses readers’ attention on the massive amount of statecraft that made this possible. Part of his goal is to make the case that the Depression and the New Deal didn’t change everything about American governance. Instead, Novak directs us to look to the period between the end of the Civil War and the beginning of the New Deal to see (a small handful of) Americans revolutionizing government structures and developing new tools that expanded their reach over society. As The People’s Welfare established, “a well regulated society” existed before the Civil War, where the mechanisms of regulation were common law decision-making and municipal statutes and corporate charters. After the Civil War, however, a more modern government sought to protect the public through public law and through state and federal regulation. The book makes a convincing case that in this era, governance—specifically the policies and mechanisms for implementing policy—was procedurally and substantively different from what came before.

New Democracy emphasizes the interplay between the expansion of public services and the expansion of legal and administrative capacity to administer them. These new mechanisms changed not just the way leaders protected the public welfare, but also the scope of the public welfare that was being protected. The book thus ties together into one cohesive story a lot of areas of law usually discussed separately but that combined to govern public life – public law, administrative law, public service corporations, and antitrust enforcement; municipal, state, and federal regulation; and administrative law administered by agencies, boards and commissions. Crucially, Novak treats all of this as a creative enterprise, not as a brake on business enterprise—part of his central interest in the creative function of law that we can trace back to Willard Hurst.

Such an expansive story about remaking government between the Civil War and the New Deal inevitably focuses more on some topics than others, and in turn raises some questions about what’s there, and what’s not.

First, ideas of “democratic” and the “public interest” are at the core of the book. Novak is using “democratic” and “public” here in opposition to “private”–not business interests but the public interest; not private ordering but public ordering; not corruption but democracy. As Novak explains, “Deweyan progressives advocated an ends-oriented democracy that turned not just on procedural inputs but on the substantive policy outputs that more equitably and effectively secured the people’s health, safety, and well-being.”[2] This approach to “democracy” raises questions about the tension between democratic methods and democratic ends, and perhaps elides the mechanisms by which those being governed made their voices heard. The book speaks of “democratic techniques of governance” but much of the story focuses on the elite reformers who envisioned what would benefit the general public.[3]

Even as both citizenship and government regulation were expanding, most adult citizens were still not able to participate in representative government, in the years before the Nineteenth Amendment and before the Voting Rights Act of 1965. And, of course, much of this power was placed in unrepresentative administrative positions intentionally insulated from politics. Novak notes the importance of considering the democratic legitimacy these unrepresentative institutions had, but here, too, I wonder about the “democratic” part of democratic legitimacy. Mia Bay’s new Bancroft-winning book Traveling Black focuses both on the way civil rights activists turned to such institutions, like state railroad boards and the Interstate Commerce Commission, to demand equality.[4] Does engagement with these institutions constitute evidence of democratic legitimacy, even among citizens excluded from representative politics? Or is these institutions’ rejection of such demands for equality evidence of the opposite?

Another key question concerns the racial and gendered and classed hierarchies built into these reformers’ idea of “the public.” The book enthusiastically describes the creative potential of these new regulatory tools, and the notable improvements to social and economic life they enabled. But, of course, along with things like antitrust law and public utilities regulation, both Northern and Southern state governments used their new legal authority to police the labor and mobility and reproductive capacities of many Americans without their participation or consent. Novak argues that the period “was permeated by a fundamental reconsideration of almost every basic doctrine in American law, politics, and governance.”[5] It’s not clear, though, that doctrines of white supremacy and patriarchy were included. In the aftermath of the Civil War, federal law and constitutional amendments rejected slavery and fundamentally reshaped legal definitions of rights but did not, as enforced, prevent the creation of new kinds of inequality that closely tracked old ones.

New Democracy emphasizes the size and scope of the state that was built, over the political tensions involved in building and legitimating this new form of government.In fact, the narrative describes a relatively seamless integration of ever more state and federal government involvement in social life. It’s worth asking, however, how the political resistance to the state might have shaped statebuilding. Who resisted, in which areas, and what were the paths not taken? How did failures direct the evolution of this modern state? And why was some of this growth without apparent tension, at least among white elites? Novak reminds the reader throughout the book that full citizenship is an unfinished promise, and that democracy remains aspirational. Perhaps, though, it’s not that Americans have simply failed to fully achieve the promise of democracy—but rather that constructing a powerful state around white supremacy allowed a larger government to be built without elite complaint, and allowed a more comprehensive expansion of discriminatory policy than would have been possible without these tools and baked these assumptions about who to regulate and how into this state in ways that endure today.

One early example raises this question explicitly. Novak quotes Joseph Beale on the law of innkeepers, hotels, theaters, sleeping cars, demonstrating the many areas of life starting to come under government regulation. However, of course, these areas of public accommodation were sites of racial discrimination and civil rights activism. And, when it came to barring racial segregation, the Supreme Court in the Civil Rights Cases emphatically rejected the kind of broad regulation for the public interest Novak discusses. Novak quotes Justice Harlan’s dissent, where the justice argued that such places of public accommodation were affected with a public interest, in line with the Court’s holding in Munn v. Illinois (1877)—but what of the conception of the public interest shared by the majority of the Court, that found such a ban on segregation outside of Congress’s authority?[6]

Finally, The People’s Welfare concludes by pointing to the two directions law takes after the Civil War: the vast expansion of a centralized government, and the vast expansion of individual rights to protect against that centralized government. A New Democracy focuses on the former narrative, focusing on regulating for the people rather than defenses to regulation by individual persons. I was thus curious how Novak would describe the individual rights narrative for this time period, and how much a robust idea of individual rights would be hostile to the regulation of “the social” or “the public” as described. Or, at least, which things that we now see as individual rights were then seen as part of the public good? We can think through this tension through state eugenics laws, where bans on contraception and abortion on the one hand, and laws prescribing forcible sterilization on the other, were all part of a fundamental progressive effort to “perfect” society as a whole. This was done with a host of procedures and bureaucratic niceties; a significant portion of the Supreme Court’s opinion in Buck v. Bell (1927) is in fact devoted to the procedural regularity of the sterilization proceedings.[7] As Novak notes, regulation in the public interest was “ever more continuous, efficacious, and expansive—capable of traversing the entire extent of the social body.”[8] If eugenics laws seem very much in line with these new governance approaches, how does that help us think through the limits of “individual rights” in this period?

These reflections are just a starting point for engaging with the many questions raised by this book. No matter the answers, I’m certain that Novak’s New Democracy has sparked a new and expansive discussion of the American state—well beyond graduate seminar rooms–for years to come.

[1] William J. Novak, The People’s Welfare: Law & Regulation in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996).

[2] William J. Novak, New Democracy: The Creation of the Modern American State (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2022), 20.

[3] Novak, New Democracy,6.

[4] Mia Bay, Traveling Black: A Story of Race and Resistance (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2021).

[5] Novak, New Democracy, 5.

[6] Munn v. Illinois, 94 U.S. 113 (1876).

[7] Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200 (1927).

[8] Novak, New Democracy, 162.