Dr. Anat Rosenberg’s article, “’Amongst the Most Desirable Reading’: Advertising and the Fetters of the Newspaper Press in Britain, c. 1848-1914,” appears in Law and History Review 37.3. This article presents a fascinating account of the relationship between newspaper publishers, advertisers and their agents, and British Inland Revenue agents, and how changes in that relationship shaped modern media. Dr. Rosenberg has agreed to answer a few questions about her article for The Docket.

The Docket: First, thank you for sharing your thoughts on your work with our readers. At the beginning of the period you write about, British newspapers were constrained by a duty on advertisements. How did the Inland Revenue assess such a tax and demarcate “news” and “advertising”?

Anat Rosenberg: Thank you for inviting me to The Docket.

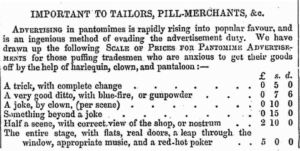

The Revenue’s practice would seem almost banal. The advertisement duty was collected directly from newspapers: the stamp authorities got copies of every issue, counted advertisements, and calculated the charge. To do that, however, the Revenue needed a rule of thumb that told its officials what was an advertisement, as different from a news item.

The implicit theory of advertising that the Revenue used in many cases was one I describe in the article as the pecuniary view. The profit motive of the advertiser was the determining question. From this perspective, if an item could enhance a business’s profit, it was an advertisement. An immediate implication was that all kinds of business name dropping gravitated to the advertisement pole. For example, an account of a horse race, a book review, a mention of musical society, a report on a celebrity arrival at a hotel, all were taxed as advertisements. Newspapers were expectedly unhappy about this and were in repeated clashes with the Revenue. Ironically, however, when newspapers had to manage the distinction themselves, after the tax was abolished, this was one of two main theories that they applied (the other theory being a professionalist one, which centered on journalistic discretion, and which newspapers had more interest in developing). The pecuniary view was a very troubled theory. On the one hand, news too involved private pecuniary interests, not least because a newspaper was itself a commodity. On the other hand, advertisements carried public informational values. How and why this theory was maintained and indeed developed and nurtured is one of my questions in this article.

Unsurprisingly, organized newspaper publishers opposed the advertising duty. But one of their most publicly and politically compelling arguments might seem strange to a contemporary reader: that taxing advertising was taxing (and therefore suppressing) publicly valuable knowledge. Was this a sincere argument or a strategic one?

It is probably the language that might seem strange to readers today, because Victorians referred to the ‘communication of wants.’ In substance, we are all familiar with the argument that advertising communicates information, which was, in essence, the argument in the historical campaign to abolish the advertisement duty. Information provided by advertisements was conceptualized as a special kind of knowledge, less abstract than political knowledge and more directly involved in mundane social interaction. Information remains a dominant justification for advertising to our own day, and a cornerstone of policy analyses, in productive tension with the argument that advertising is persuasion.

To the issue of sincerity and strategy in this argument, we will probably find a mixture of both in virtually any historical (and present) position; individuals, and more crucially groups and cultures, need to justify their choices to themselves no less than to others. Even if some individuals are strategically motivated, they would need significant cultural resonance to succeed, which depends on some level of conversion to the argument’s merit. Whether strategy or sincere belief explain a particular cultural viewpoint will therefore typically be something of a chicken-and-egg problem. Perhaps we shouldn’t try to separate them. In the article I argue as much, by focusing on another dilemma between sincere and strategic positions: newspapers tried to assume the role of sincere (unbiased) reporters of information, and to attribute to advertisers all the bias of strategic behavior (the profit interest). The reality, however, was more complex than that.

To the extent we try to disentangle strategy and sincerity in the argument that advertising was valuable knowledge, strategic concerns would appear immediately obvious. The argument was strategically useful for supporters of the tax reform who were interested in freeing the press from traditional forms of political control (as the article observes, this by no means meant freedom from politics; the change in forms of political power after advertising became the press’s financial engine remains a hotly debated question, long after Jürgen Habermas’s argument in The Structural Transformation the Public Sphere). The argument was useful for advertisers, of course. And as you say, the argument was also strategically useful for many newspapers. Notably, not all newspapers; the Times, for example, benefited from the taxes, because they protected its dominant market position; but the argument was attractive for smaller papers and aspirants who faced entry barriers into the market. Therefore, it may be worth emphasizing elements that we could call ‘sincere.’ For one, the argument that advertising was knowledge had early roots in the era that preceded mass print media, when entrepreneurs tried to create a “register of wants” to facilitate exchange and commercial communication. It also had more recent roots in the 1830s struggle to remove the taxes on the press, which were already dubbed ‘the taxes on knowledge.’ By the mid-nineteenth century, this argument rang obviously true, or at least familiar for many people. Moreover, there was much to be said, sincerely, for the argument: it was difficult to deny that readers gained some form of knowledge from advertisements.

However sincere or strategic, in the article I am especially interested in the appeal of the argument that advertising was knowledge. Unleashing advertising could seem threatening to those who worried about the participation of masses in the market. Framing advertising as knowledge soothed concerns by depicting advertising as a neutral tool of individuals, rather than a socially transformative force. It described market-oriented individuals, separately seeking to sell, buy, and work according to their separately predefined wishes and needs (‘wants’). Advertising merely functioned as a channel for communicating these wants. Alongside the soothing individualism, the argument implied a view of national life as a peacefully rational coordination through free trade communication, which cut across political discord. I have found very few substantive objections to the argument. Advertising was mainstreamed on these terms with such force that newspapers soon had to push back.

The repeal of the advertising duty caused unexpected problems for newspaper publishers, however, as advertisers recognized their importance to the papers. How did publishers try to control this relationship and demarcate boundaries between news and advertising on their own terms?

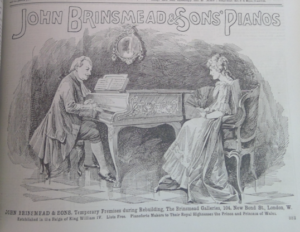

With the repeal of taxes, the press’s financial basis shifted definitively to advertising. Newspapers grew extremely rapidly, but advertisers began to undermine owners’ control of the medium, in various ways. They might have wanted free publications of their materials – which, they said, were public information that newspapers must deliver. Or they might have been willing to pay but required a say about the placement of publications, in news or editorial columns, or without conventional marks of advertisements. Or they might have conditioned a contract for paid advertisements on a newspaper’s willingness to include additional material that they offered. Essentially, advertisers resisted distinctions between advertisements and news. If, as the midcentury legislation confirmed, advertisements were an informational realm, then their position made sense. Newspapers had to push back against the midcentury paradigm of advertising as information.

The press was not unionized, but there was a form of soft normative organization through the Newspaper Society, which represented a major part of the newspaper press. The Society collected data on newspapers’ relationships with advertisers, and their everyday legal practices, disseminated it to editors and owners, and published normative recommendations. We see a host of normative efforts by newspapers, on a number of fronts: organizational structures for the collection and news and advertisements, management of employment and contractual relationships with advertisers and agencies, and policies of publication. These efforts cumulatively implied and applied a conceptual distinction between advertising and news. According to newspapers, advertising was indeed information, but inherently biased information, unlike news. Put otherwise, newspapers created a hierarchy of informational categories; advertising was inferiorized, and news correspondingly elevated.

The hierarchic distinction between news and advertisements was theoretically weak, and in practice often honored in the breach. The structural realities of the press militated against strict observations of boundary lines. There was simply too much economic dependence and organizational porousness. However, the normative investments of newspapers managed to spawn a vision of advertising as an inferior informational category, that by 1914 resonated as simple common sense. From a cultural history perspective, this was a significant achievement. The many modes of asserting the inferiority of advertising vis-a-vis news managed to maintain a system of publication that drew profit and enjoyed social legitimacy.

Finally, one of the most arresting aspects of your research is how you document the incredible (and often outlandish) degree to which Victorian businesses worked to make their products “news.” I expect readers will be struck by the similarities with many of today’s media practices (e.g. product placement, public relations, and even “influencer” culture). How does your research speak to today’s concerns about “fake news”?

You can see here early iterations of fake news, with a dual takeaway for today’s debate. First, fake news is an old problem. Second and more importantly, history can point us to its roots.

In popular discourse today, the debate is sometimes reduced to true versus false facts. This popular form was widely familiar among Victorians too. Advertisers sometimes invented things that did not happen, such as a story of a road accident made up to advertise a shop, and they were derided for that reason. But the deeper question, which also lies at the basis of the present predicament, is the process of knowledge production, and our cultural ability and willingness to trust it – and to doubt it. Those who produce fake news today, or throw ‘real’ news into doubt, are successful because their supporters are disposed to suspect dominant structures of knowledge production, but equally disposed to accept alternatives by default. These tendencies are turned to potent political use.

In the article I examine the historical moment of the press’s move from one problematic structure of knowledge production to another: from dependence on political patronage, to dependence on market patronage. The fake news that advertisers sometimes produced highlighted that newspapers themselves were susceptible to that risk: their dependence on advertisers compromised their ability to screen these publications. Much more deeply, however, advertisers actually created news, that is, they orchestrated events that became, necessarily, part of reality, and made news. In the article I discuss a row in a theatre that reached the King’s Bench and became the legal precedent of Dann v. Curzon (1911), and was entirely orchestrated. The very category of reality was challenged. And again, newspapers were susceptible to this challenge. Concerns about advertising’s construction of reality reflected on that of newspapers. Simply put, the key problem was and remains: how is the category of news defined, and defended?

When we say “fake news” we imply a breach of an ideal of authentic or real news. However, from the first moment of the modern commercial press, there was a spectrum of options, none of them ideal, but, of course, some better than others. The challenges had to be managed, and most crucially – acknowledged. However, the historical policies of newspapers often consisted in idealizing news as unbiased, which they did by scapegoating advertising as the carrier of all biases. The superiority of news was more often asserted than convincingly explained, all the less practiced. Such idealization worked with reified categories, and evaded rather than acknowledged dynamic structural problems. This was a fragile manner of facing susceptibilities, which unsurprisingly collapsed every so often. Recalling this history denies the option of simple idealizations and longings for a better past. It invites instead a persistent engagement with the fact that all choices are part of an imperfect spectrum. Any choice becomes stronger the more it is questioned, rather than reified in a game of arm wrestling.