Editor’s Note: This issue goes to press in the wake of much-watched elections in several southern states. The Docket asked historians to share commentary on resonances between their own research and the past election. Among other results, African American Democratic candidates in Georgia, Florida and Mississippi mounted competitive campaigns in statewide elections despite new election laws making voting more difficult. R. Volney Riser has written about African American voting rights activists and election law at the dawn of the Jim Crow era, and is at work on a manuscript on anti-democratic doctrine and a legal biography of Booker T. Washington. He has agreed to answer a few questions from The Docket about the midterm results.

The Docket: First, thanks for taking the time to field a few questions. To set the table, I’d point out that many historians and other scholars have revived attention to the period following the end of Reconstruction as comparable to our moment. Notably, after Shelby County v. Holder (2013), many states (chiefly though not exclusively southern) have explored similar changes to election law that carry disparate racial impact and make it generally more difficult to cast a ballot. Does your research speak to this aspect of disfranchisement as a process rather than an event?

R. Volney Riser: Yes. I think most people’s knowledge of disfranchisement comes from what they learned in a U.S. history survey, it’s easy to compress that into an event. We tell a class that disfranchisement happened, and it necessarily can come off looking like a discrete thing that just happened at a specific point. There was a point in the mid-1890s on the heels of the Populist Revolt where the movement accelerated rapidly, but groundwork was established long before that. Also, there’s a confusion about the difference between suffrage restriction and disfranchisement. The former means you’ve interfered with the act of voting and the latter has to do with the definition of citizenship itself.

Something I noticed my research for Defying Disfranchisement was a sense among some African Africans—middle class, propertied, educated African Americans—that the disfranchisement movement had taken them by surprise. They’d done everything they’d been told to do, they’d acquired property and earned educations and paid their taxes, and many seemed astonished to learn they’d been the targets all along. Yet, for the better part of two decades, Southern Democrats had complained of black suffrage, had interfered with African Americans’ ballot access, and had expressed in clear terms their wish to strip them of this badge of citizenship.

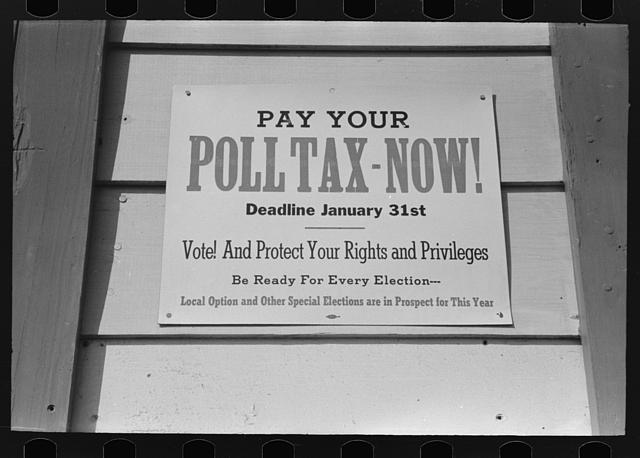

To bring this up to the present, we’re caught up now in an orchestrated and accelerating push to restrict suffrage, but this hasn’t just begun out of the blue. It was moving in earnest by the early 2000s at least, for example with the U.S. Attorney firings scandal of the George W. Bush Administration, though it only became a frenzied crusade after Barack Obama’s 2008 election. And let’s be clear: that’s no coincidence, and it’s not Obama’s “liberal” policies the neo-disfranchisers are reacting against. So the process is unfolding once more, and neo-disfranchisers have a whole new set of tools at their disposal. It won’t this time be a literary test or an understanding clause or a poll tax—this time it’s predictive modeling, pseudo-scientific handwriting analyses, coding “errors”, data harvesting, etc.

Much recent legal fighting around disfranchisement seems to revolve around, on one hand, articulating color-blind justifications for restrictions, and on the other, arguing that those justifications conceal plainly racial intent. Can you sketch out the lines of conflict in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries with respect to intent, result, and constitutionality?

Understand first that the disfranchisers of the late-nineteenth century and the anti-disfranchisement activists were operating in a legal world completely different from our own, both in philosophical and practical terms. Philosophically, formalism remained firmly entrenched along with the common law regime. Practical differences were no less an issue. Here again, common law was a factor, as was the fact they were arguing something entirely new. There was no such thing as nationally-defined U.S. citizenship before 1868; the very idea of state-defined, codified citizenship in the modern sense was barely a century old; there was no body of jurisprudence upon which they could draw. What this added up to was a system that was not equipped to receive individual rights claims, and lawyers who also had no idea what form an individual rights claim might take. Moreover, you find African American voting rights activists taking as their starting point the sort of respectability politics that might in a present-day scenario be highly controversial.

Another extremely important difference concerns the terms of the debate. In 1900, in any southern state, it was rare to find a conservative Democratic partisan who didn’t openly boast and brag how the new suffrage restrictions would make it impossible for black men to register and vote. I don’t mean in private conversation, I mean in public, on the campaign stump, in pursuance of their public duties. The legal regime they operated under taught them they could do whatever they wanted and to who so long as the law on its face, in its clear terms, did not discriminate. Today, we are conditioned to argue in terms of a law’s effect. Even with the disaster that was Shelby County, the terms of debate and the field of play remain radically changed from those confronting anti-disfranchisement activists of the 1890s and early 1900s.

Today as in the 1890s, party identification is starkly polarized by race, and the question of who may vote holds partisan implications. What does your research show about the risks and potential of fights for voting rights that are strongly tied to partisan interest?

Partisan interests historically have been everything, and they’re everything now. Racist concerns and questions of identity have also been foundation to American partisanship since at the least the mid-17th century in the English colonies. I don’t know that I’d say there were “risks” of partisan-oriented voting rights struggles so much as there can be risks to partisans in those episodes. Overreach is an equal-opportunity danger. An interesting wrinkle in what we see now is that though we’d typically describe the Republican party of 2018 as effectively the “white party,” they don’t actually even have a lock on white voters. Rather they have trended more male, older, less-educated, more rural, and poorer. None of these (except poorer) are growth categories.

What was the nature of “anti-democracy” in the Jim Crow era?

Well, anti-democracy then as now was concerned first with ensuring that as few adult citizens as possible had the right to vote, and that as few adult citizens as possible had the ability to cast an actual ballot. Second, and no less important, it was then as now concerned with insulating government from popular will. Southern states’ disfranchising constitutions were replete with measures obstructing local control of anything, limiting constitutionally the ability of the state legislature or of municipalities to regulate or tax anything, and for any purpose. For a good modern example, look to what Wisconsin Republicans are this week enacting, or look at the suite of measures North Carolina Republicans have these past two years launched in an attempt to thwart popular majorities.

The basis for present-day anti-democracy, and the basis for it in the early twentieth-century South, was gerrymandering. What the southern states did was apportion their legislatures on the basis of geography, guaranteeing that “pork chop gangs” of rural legislatures would control urban population centers. Clear Supreme Court precedents addressing “one man, one vote” mean the neo-disfranchisers have to work a little harder. Since 1990, map-drawing has reached ever more absurd heights, and its primary aim is to preserve minority control. Ascendant Republicans have bleached districts, atomized Democratic constituencies, and created bizarre situations such as Wisconsin—the new Mississippi—where you have 54% of votes cast for Democratic legislative candidates, yet Democrats somehow secure only 36% of legislative seats.

What I’m looking at in my current research is how southern policymakers attempted to sell their version of antidemocracy to a skeptical nation, and how national public option shaped what the disfranchisers did. It was all an effort to reassure themselves the federal government wouldn’t be roused, that they’d face no punishment for nullifying the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. And they spent years and years in search of a tacit endorsement that never came. With today’s efforts, I’d say the nature of it “feels” synonymous with past precedent, and I think the neo-disfranchisers are every bit as brazen as their forebears, but I’m not sure they have the intellectual heft and political talent to pull it off, not in the long term.

Regardless of the final outcome of elections in Georgia, Florida and Mississippi, black candidates for statewide offices there have mounted highly competitive campaigns, with minority voter turnout and litigation challenging allegedly discriminatory voting procedures playing key roles. What more should our readers know about the historical activism you have written about as they consider current events?

It’s cliché to point to this out, but American history has not been marked by a steady progression toward a full realization of the founding promise. There has been progress, but it is halting and slow—almost Sisyphean. Shelby County v. Holder is a perfect example of that. Jackson Giles, Cornelius Jones, Wilford Smith, Booker T. Washington—they all made very modest requests, and they came away with nothing to show for it. Today, we aren’t going to see litigators asking for crumbs—they’re going to confront Leviathan head-on, and they have numbers and time on their side. Further, something we’ll get to see unfold shortly is the effect of Florida’s felon disfranchisement amendment, which will have the effect of re-enfranchising upwards of forty-percent of the African American male population. Adams, Gillum, and Espy have all three lost, but they also all three came awfully close to winning. Think about that: for all the efforts in recent years to make it impossible for Democratic-leaning constituencies to vote, all three of those candidates polled awfully well. I think the intelligent prediction is to say in the short term these voting rights battles will get uglier, and they will be ever more obscene. Remember, too: there probably were no more than a dozen active civil rights litigators at the turn of the twentieth century, and now they are legion.