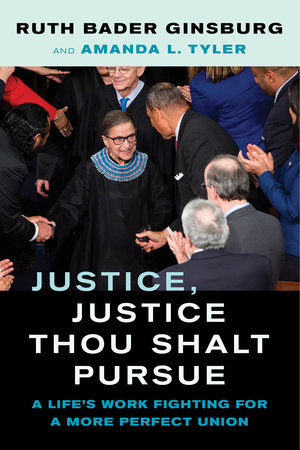

This past summer, The Docket asked Professor Cary Franklin to interview Professor Amanda Tyler about Tyler’s new book, Justice, Justice Thou Shalt Pursue: A Life’s Work Fighting for a More Perfect Union (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2021) which she coauthored with the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. We are please to bring you their expansive discussion about the book’s main topics, the importance of judicial dissents, and Justice Ginsburg’s vision, among other topics. The Docket also wishes to thank Alex Shapiro of the University of Berkeley Law for assistance with materials featured in this interview.

Cary Franklin [CF]: Thank you so much, Amanda, for your work on this project. The book contains a wide variety of historical materials and could have felt disjointed, but you identify and make visible several narrative threads that knit the material together. This editorial vision helps to make the volume even greater than the sum of its parts. I wanted to start by asking about your editorial vision. Justice Ginsburg was an incredibly prolific writer over many decades, so when it came to selecting pieces for inclusion in this volume, the possibilities were practically endless. Could you say a bit, in general terms, about how you and the Justice decided what to include and what you hoped to convey with your choices?

Amanda Tyler [AT]: Of course. Let me start by saying thank you for the opportunity to talk about Justice Ginsburg and the book. It was such a huge privilege for me to work with her on this project, especially since it gave me the chance to work closely with her some twenty years after my clerkship.

As we were thinking about the book, we had two main goals in mind: first, to track the conversation that we had about her life and complement it with materials that spanned the same range of coverage, and second, to create something that would be accessible to a broad range of readers. On the first point, we tried to choose pieces that would offer a window into some of the work that was very much at the heart of the Justice’s legacy as an advocate and judge – namely, her work for equality, both as it relates to gender and also voting rights and race. We also wanted to offer a window into the person behind the work, which I hope we were able to do through our conversation and through, among other things, including the final speeches that she delivered at the end of her life. As to the matter of accessibility, we tried hard to be discerning in what we included so as to reach both lawyers and non-lawyers alike. And this also meant trying not to bite off too much. As you reference, the possibilities for inclusion were massive, and what we did not want to do was create something so big that it would be intimidating to crack the book. I hope we succeeded on these fronts.

CF: My second question follows from the first. The lengthiest section of the book reproduces four opinions that Justice Ginsburg authored in her time on the Court. The book bills these opinions (United States v. Virginia, Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., Shelby County v. Holder, and Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc.) as Justice Ginsburg’s “favorite opinions.” I am sure the Justice was fond of these opinions for various reasons, but she was a lawyer through and through, so I imagine that when she selected these four opinions, she was, at least in part, making a set of legal arguments. Could you talk about what she was trying to communicate with these selections?

AT: Putting this part of the book together was so interesting. The Justice very quickly came to identify these four as her favorite opinions of the over 480 she wrote on the Court. (Note she also wrote some 700 on the D.C. Circuit.) At various points as we continued work on the book, I suggested other possible opinions for inclusion. Nope, she said, these were the four. Why? Well, I cannot speak for her, obviously. But I think the inclusion of VMI was a no-brainer. Here is an opinion in which she gets to write for the Court striking down a practice that discriminates against women and therefore she gets to play a part, now as a judge, in opening up opportunities for women. Of course, this opinion was so special to her. She was able to cite the precedents that she had worked so hard to win in the 1970s. As I discuss in our introduction, she also wound up writing the opinion only because Justice Sandra Day O’Connor declined the assignment, saying it should go to Justice Ginsburg. She was so grateful to that and she returned the favor by relying heavily in VMI on Justice O’Connor’s opinion in Mississippi University for Women v. Hogan. Finally, as Justice Ginsburg explains in the conversation part of the book, VMI provided the opportunity for her finally to win a case in which she had participated in the 1970s that did not meet with success at the Court, Vorcheimer v. School District of Philadelphia. (In that case, the Supreme Court affirmed by equal vote the decision of the Third Circuit upholding separate and very unequal high schools for high achieving boys and girls in Philadelphia.)

As for the remaining opinions she included, they are all dissents. I do not think that this was any accident. Recall we assembled this book in 2019 and 2020. I think Justice Ginsburg wanted to convey that she believed the Court had really veered off course in these cases—cases that involved matters deeply important to her and all that she had spent her life working to advance in terms of advancing a more equal society. These are cases about general equality, voting rights and racial equality, and reproductive freedom for women, which she believed was a crucial component to true gender equality. In other words, I think her choices here were meant to call on the rest of us to continue these fights.

CF: One theme that leapt out particularly strongly to me when reading these opinions is Justice Ginsburg’s deep commitment to purposivism and pluralism in the interpretation of statutes and democratic constitutionalism in the interpretation of the Constitution. In Ledbetter, for instance, she repeatedly criticizes the Court for interpreting Title VII in a “cramped” way, “incompatible with the statute’s broad remedial purpose.” In the VMI case, she observes that “[a] prime part of the history of our Constitution . . . is the story of the extension of constitutional rights and protections to people once ignored and excluded.” In cases where the Court has been involved, these extensions have generally occurred in non-originalist ways. Indeed, Ginsburg’s own victories at the Court in the 1970s were non-originalist. But in the later years of her career, the Court became increasingly dominated by proponents of textualism and originalism. What do you think it was like for the Justice to work on a Court increasingly (though inconsistently) committed to methodologies with which she disagreed?

AT: I imagine that it became increasingly frustrating for her to see the Court interpret statutes and the Constitution in such a cramped fashion. One scholar, Henry Monaghan, once referred to her interpretative approach as taking a purposivist approach to originalism. I think that’s pretty close to the mark. She would ask what was the purpose behind this provision in the Constitution or this statute. And often history and context could, along with the text, help shed light on purpose. She read the Equal Protection Clause to provide, as its text clearly does, very broadly for equality. Why would you read words that are written at such a high level of generality in such a cramped fashion instead of consistent with a broader purpose? The same could be said of Title VII as it was at issue in Ledbetter. By its terms, Title VII purports to go very far to try and level the playing field in the workplace. In Ledbetter, she seems to be asking why would you read the statute in a way that is completely untethered to the real world and in so doing effectively render the statute meaningless to address long-term pay discrimination? I’d like to think that she took some satisfaction in seeing at least some of her colleagues right that wrong in Bostock, where the Court finally returned to a recognition that Title VII was intended to change the landscape of the workplace by eradicating a very broad range of discrimination based on gender and related factors.

CF: In addition to these four opinions, the book contains a transcript of a public conversation you had with Justice Ginsburg at Berkeley in 2019. You note in the book that you had intended to ask the Justice about the Equal Rights Amendment but that time ran out before you could broach the subject. I was hoping you could discuss the Justice’s views on the ERA and how the arguments that animate this volume, and that helped to fuel Justice Ginsburg’s long career in the law, might inform the debate over the need for the ERA in the twenty-first century.

AT: Oh, how I wish we could have squeezed that question in during our public conversation. I will share that she was asked about the ERA earlier that same day during a lunch event. She said there what she had said on many other occasions—namely, she longed to open a Constitution to see express recognition of the equality of the genders among its core principles. She elaborated on this point in a 2001 interview:

“[T]o think that the U.S. Constitution doesn’t make that basic statement, when almost every post-Second World War constitution does, says something about our society. U.S. children studying the Constitution in their civics class won’t see that basic statement. Children elsewhere will. It is a basic statement for the century just beginning. It is certainly a fundamental human right that men and women should have the chance to pursue whatever is their God-given talent, and not be held back simply because they’re male or female. The Equal Rights Amendment is an expression of that idea, and I think for that reason it belongs in the Constitution.”

CF: This book arrives on shelves in the midst of one of the most vigorous debates over court reform we have had in this country in nearly a hundred years. Some of this debate was sparked by the events that followed the Justice’s death, but some progressive sentiment was turning against the Court even prior to that, as you were putting the book together. I wonder if you and the Justice thought about the image of the Court you wanted to project in this book. Or, if that wasn’t topmost in your mind, I wonder if you could comment on how the history this book recounts (much of which revolves around the Court) might inform how we think about the Court and court reform in 2021.

AT: During the time she and I were assembling the book, we did not discuss the various proposals for Court reform that were already starting to gain more prominent traction in public debates, so I cannot share anything on that score. I did try to touch on this a little in the Afterword, though. Justice Ginsburg always played the long game, and throughout her life, no matter how discouraging things were, she remained fiercely optimistic. When I talk to my students about what she taught me, I paraphrase it this way: roll up your sleeves and keep doing the work. She often spoke of how much progress she had witnessed in her life, particularly with respect to advancements in racial and gender equality. But she also never shied away from calling out injustice on both scores when she saw it and therefore highlighting just how much work remains to be done. I think by including the dissents she chose for the book, she was very publicly trying to enlist the next generation to keep up the fight—to keep doing the work and not give up, no matter what.

CF: In addition to being published in the midst of debates over the ERA and court reform, this book is being published in the wake of a stunning proliferation of state laws restricting access to abortion. Indeed, the book came out at about the same time as the Court’s decision to grant certiorari in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization—a case that might spell the end of Roe v. Wade. The book does not address abortion or the regulation of pregnant women at all, which surprised me a bit. Justice Ginsburg was an important voice in debates over the rights of pregnant women for decades—from her days as an advocate, in cases such as Struck v. Secretary of Defense, to her time on the Court, in cases such as Gonzales v. Carhart. Did this material just get crowded out? Was there an affirmative decision to focus on other topics (some of which are related—such as the fight over the contraception mandate in Burwell—but don’t directly involve abortion)?

AT: As I said earlier, one of our decisions at the outset was to try and create a book that was accessible, and unfortunately that meant that we could only include so many opinions. I think she chose to include her dissent in Hobby Lobby to speak not just to contraception, but more generally to spell out in detail how and why she believed reproductive freedom is a crucial component to gender equality. There certainly was no conscious decision to shy away from abortion when it came to the book’s coverage, and anyone who knows Justice Ginsburg’s track record knows that she was a fierce defender of a women’s right to choose whether to carry a pregnancy to term, for all these very same reasons.

CF: In the year that you and the Justice were working on this book, the Court was deliberating over Bostock v. Clayton County. As you were finishing the book, the Court issued its decision in the case, holding that Title VII’s prohibition on sex discrimination bars discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. Although Ginsburg did not litigate LGBT rights cases, her framing of the 1970s sex discrimination cases, and her work on behalf of male sex discrimination plaintiffs, laid a critically important foundation for the Court’s ruling in Bostock. Did the Justice reflect on this history when Bostock came down? What did she think about current and future extensions of her monumentally important work challenging the enforcement of sex stereotypes? Did she think about where this line of cases—extending back, at least, to her earliest victories at the Court and running through Bostock—might go in the future?

AT: In some respects, I have already touched on this insofar as I think Bostock marked a return to a common sense approach to interpreting Title VII consistent with what the law was supposed to achieve—namely, the eradication of discrimination in the workplace based on assumptions related to gender and gender stereotypes. And I do think you are right to connect this in part to Justice Ginsburg’s work in the 1970s. A big part of what she tried to do there was explain how gender discrimination cuts in many different directions and therefore holds back not just women, but sometimes men as well. Bostock extended that idea to show how the same traditional stereotypes and/or assumptions about gender can have profoundly bad effects on the LGBTQ community as well. I cannot speak specifically to what she hoped this would mean going forward, but I do feel comfortable saying that she must have hoped that Bostock would mark a return to a recognition that any cramped reading of Title VII, like we witnessed in Ledbetter undercuts the very premise of the law. And reading a law like Title VII—that, let’s be clear, by its very terms was intended to make sweeping, progressive changes—in a cramped fasion holds us back as a society in terms of opening up opportunities for all individuals to thrive and achieve their full human potential, a goal Justice Ginsburg worked toward in all that she did.

CF: As you note in the book, Justice Ginsburg was a deeply optimistic person. Hope is one of the strongest themes in the book. Even the decision to include four dissenting opinions as her “favorites”—which some people might view pessimistically—was, for Justice Ginsburg, an optimistic choice. She thought of herself as writing for the future, for a (better) day when the Court becomes more willing than it is today to use its power to protect marginalized groups. Do you think Justice Ginsburg had a purely whiggish view of history? One can certainly understand how someone whose legal career began in the Warren Court era, who witnessed what Thurgood Marshall accomplished, and who went on to accomplish similar feats herself, might develop a powerful belief in progress and the Court’s role in fostering it. Do you think her faith in the progress narratives associated with the Warren Court era ever waivered, or was she steadfast in her faith that—despite certain setbacks—we are generally and inevitably on our way to becoming a more perfect Union?

AT: As I have said, I hesitate to speak for her, but my own impression is that even at the end of her life, she was still hopeful and still very much in the fight. She was, to borrow from something I said earlier, still rolling up her sleeves and doing the work. Someone who did not believe that work was worthwhile could have easily let up. (She presided over oral arguments during the pandemic from a hospital bed!) So I do think she remained hopeful that the long arc of history will bend the way so many of us hope (“toward justice”), but she was also realistic. As she finished Dr. King’s famous quote in her Shelby County dissent, she noted that this is only going to be the case if there is a “steadfast commitment” to that end. In this moment, we stand on something of a precipice. Will we keep things moving forward in building that “More Perfect Union”? Or we will turn backward, as I think she believed the Court was doing in many recent cases in which she dissented? Unfortunately, she is not here to guide us, but given my experience working with her on this book, I think she would say to those who share the same steadfast commitment she possessed: roll up your sleeves and get to work.