Introduction | Kalyani Ramnath

Historians have shown how legal actors in colonized spaces encountered, used, and understood law, shaping everyday legalities. In the reflections that follow, the authors draw attention to the materiality of legal spaces of law and justice; spaces of adjudication such as courtrooms and clerks’ offices, spaces of banishment and confinement such as prisons and palace chambers, and places often considered marginal to the processes of imperial law, such as islands and highlands. Colonial legal spaces influenced how law was made available, accessed and executed, but also how people improvised spaces to make law’s meaning apparent, make it more legible, or indeed, to set the stage for its violent performance. These spaces were organized, systematized, and materialized with objects such as pens, tablecloths, proofs of evidence, and scraps of paper. But alongside trial transcripts and case papers, photos, drawings and maps make up the everyday materials of colonial law that often elude the written record of legal proceedings. In these reflections, the authors pay close attention to building plans and boundary markers, to caps and cloth and ornaments, to sediment and detritus. They look at the afterlives of colonial legal spaces imprinted on landscapes and seascapes. These reflections draw from wide-ranging scholarship and extensive expertise on the Spanish, Dutch and French empires: the Spanish empire in the Americas in the case of Premo and Yannakakis, the Dutch empire in present-day Southeast Asia in Ravensbergen’s example, and the French empire in Wood’s notes. These reflections, drawn from larger research agendas, are intended to generate conversations on the value of comparing, connecting and finding overlaps in the materiality of legal spaces, within and across empires. We might also read them as spatio-legal history that takes refashioning and ruination seriously.

The Half Real Court: Mexico’s Juzgado General de los Naturales | Bianca Premo

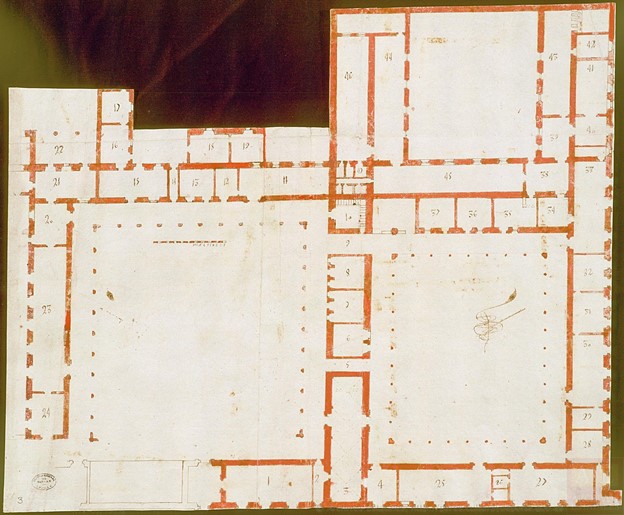

A medio-real. Around 1/16 of a peso. This is what Indigenous men in the Viceroyalty of New Spain had to pay yearly to support the Juzgado General de Naturales, a special court for natives presided over by the viceroy from his palace in Mexico City. Indigenous petitioners from its vast jurisdiction arriving in the capital’s central plaza around 1700 discovered that their half-real paid for only half a palace. The building had been torched in 1692 during an uprising later characterized as an “Indian riot.”

The Juzgado attracts legal historians because it retrofit medieval prerogatives for “miserables” to a uniquely colonial purpose. Indigenous people were express-routed to royal favor through the court, where their petitions were handled summarily, often by viceregal fiat rather than litigation. Also called the “court of the half-real” because of the tax levied on Indigenous subjects, this was a “half real court” for other reasons too, including its elusive material presence.

It is difficult to locate where in the palace viceregal audiences occurred and even whether Indigenous petitioners met face-to-face with the viceroy with any frequency at all over time. If remanded to the court’s judicial functions, litigants’ interactions inside the Real Audiencia’s courtroom become clearer but still not fully visible. This unique colonial jurisdiction was as much a space of absence and abstraction as of pomp and protocols.

In the 1550s, the first viceroy received native petitioners directly, in person and in the palace, so close he sensed their “stench and heat.” After its formal founding in 1592, the Juzgado attracted even more petitioners. But the viceroy’s accessibility to Indigenous subjects posed a political problem. One complained of the lack of “decorum in a place that stands in for (theniente) Your Majesty in seeing public hearings like an ordinary judge over causes of very little importance…in front of a lot of people… of very ordinary quality, who will notice [only] what they each wish.”[1]

The viceroys then retreated from view, leaving most decisions to a proxy, the asesor. His oversight was represented by a rubric on paper exchanges, not interpersonal ones. Indigenous subjects increasingly sent representatives bearing petitions created in the pueblos to submit to the court’s paid solicitors, whose tables lined the palace corridors. Palace doormen, who continually asked to be put on the half-real payroll, regulated access for Indigenous petitioners– no more than two were to ascend to the offices and courtrooms of upper chambers through back stairs. Over time, administrative legal business was moved from the warren of offices and courtrooms to the viceroy’s private residence, where it disappears from floorplans. Instead, from an office adorned with one single wood cabinet, an official scribe standardized viceregal rulings in uniform handwriting.

This dislocation might mean the Juzgado was less an embodied encounter than a figment of the colonial political imaginary. Perhaps all that paper facilitated Indigenous petitioners’ abstraction of the court as a locus of justice rather than a real place where, if they approached near enough, they would perceive the viceroy’s own “stench and heat.” But imaginations were not unlimited.

When the fire tore through the palace in 1692, it reached its interior, including a space Baroque intellectual Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora called the “Juzgado de Indios.” Sigüenza was especially preoccupied with saving the palace archives, where sovereignty had come to reside. Below, on the smoky street, an official asked one rioter what he was doing. The answer: “I swear to Christ those legal bureaucrats who do nothing but push paper… must die.”[2]

People, Paper, Cloth: Mixed Courtrooms and Materiality in Colonial Indonesia | Sanne Ravensbergen

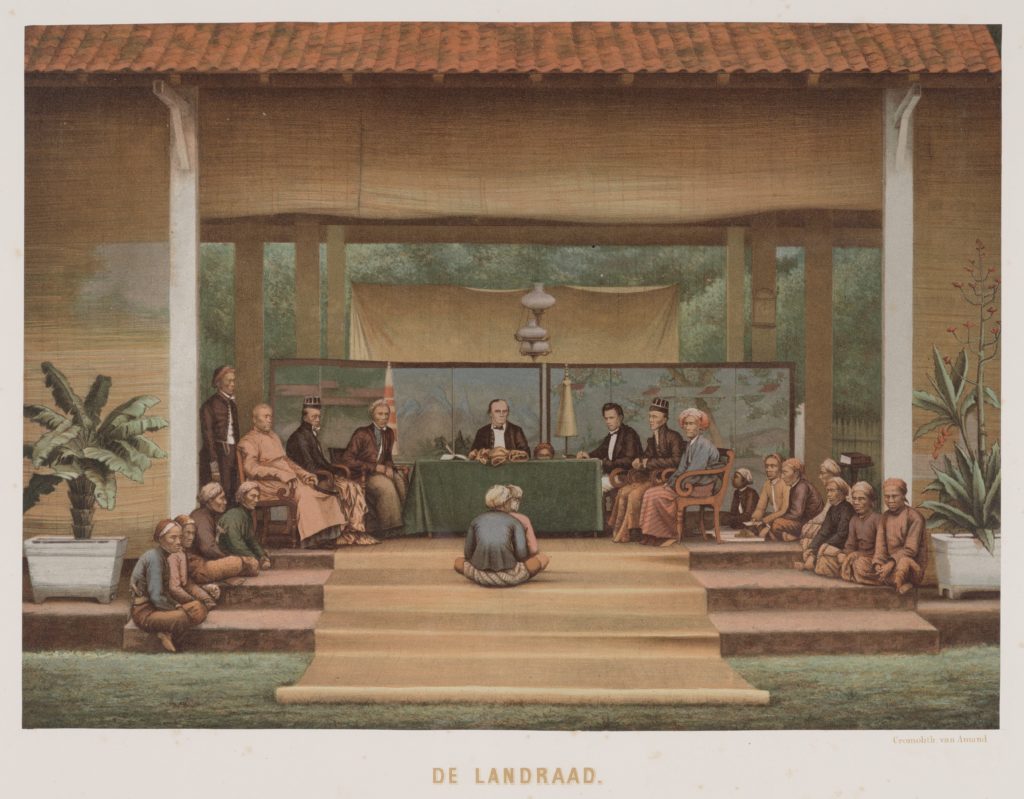

Javanese and Dutch elites in colonial Indonesia eagerly embraced the new technology of photography in the second half of the nineteenth century. They commissioned photos to be taken of themselves and of the mixed law courts (landraad) where they held judicial positions. These photos display spaces—inside court buildings in cities or outdoors in the countryside—that were transformed into legal spaces with the use of a plurality of materials.

These visual dimensions of law-making offer a distinct way to think about legal pluralism. The mixed courts captured in black and white, were central sites in a Dutch colonial state based on a combination of dual rule and segregation. The photos are so abundantly “filled” with people, paper, cloth and other objects, that we constantly change the aperture, to focus on something or someone else. What one observer might see, the other might not. And this was perhaps not that different at the time. The material objects in the courtroom sent their own distinct messages and signals, sometimes tailored for the entire audience, sometimes only for certain observers.

The Dutch judge would ensure that the table of the, improvised or not, courtroom was always covered with a green tablecloth, which from a European perspective represented a table where important decisions by men of power were taken. The batik, pajong (umbrella) and kuluk kanigara (hats) worn by the Javanese court members, additionally, indexed the complicated array of status within Javanese society. The so-called ‘forbidden patterns’ of batik were only allowed to be worn by aristocrats of a certain rank and signalled to the Javanese observer the status of the Javanese judges as well as their kinship to rulers in the semi-independent Princely states. Amulets could be hidden in the head scarfs of the witnesses and were understood to secretly nullify the powers of the oath taken by holding the Quran above the witnesses’ head. The plurality of materials simultaneously provided possibilities to impose colonial rule, to insert oneself in an alternative hierarchy, or to resist.

Fearing the invisible yet promoting the visible, the Dutch aimed at using a plurality of cloth to strengthen the colonial state. Visibility was important to them as they largely ruled via the established authority of the Javanese priyayi. However, it was a visibility framed on the colonizer’s terms. When Soekarno, the future Indonesian president, in 1930 used the space of the Bandung landraad to exercise his right to speak and delivered a strident anti-colonialist defense entitled “Indonesia Accuses”, the colonizer hastily returned the landraad space to its safe invisibility: the next time Sukarno fell afoul of colonial restrictions on speech, he did not get a trial, but was given political exile instead.

The landraad photos show a courtroom where different actors were signaling distinct messages to multiple audiences. Studying the materials in these photos, with their visible and invisible messages, provides insight into the various layers of (mis-)communication that were inherent to the mixed courtroom. A room filled with paper, people and cloth, with a plurality of languages, symbols, interests and ideas. In this mixed legal space, objects often spoke louder than words.

Out of Bounds in the Circum-Caribbean | Laurie Wood

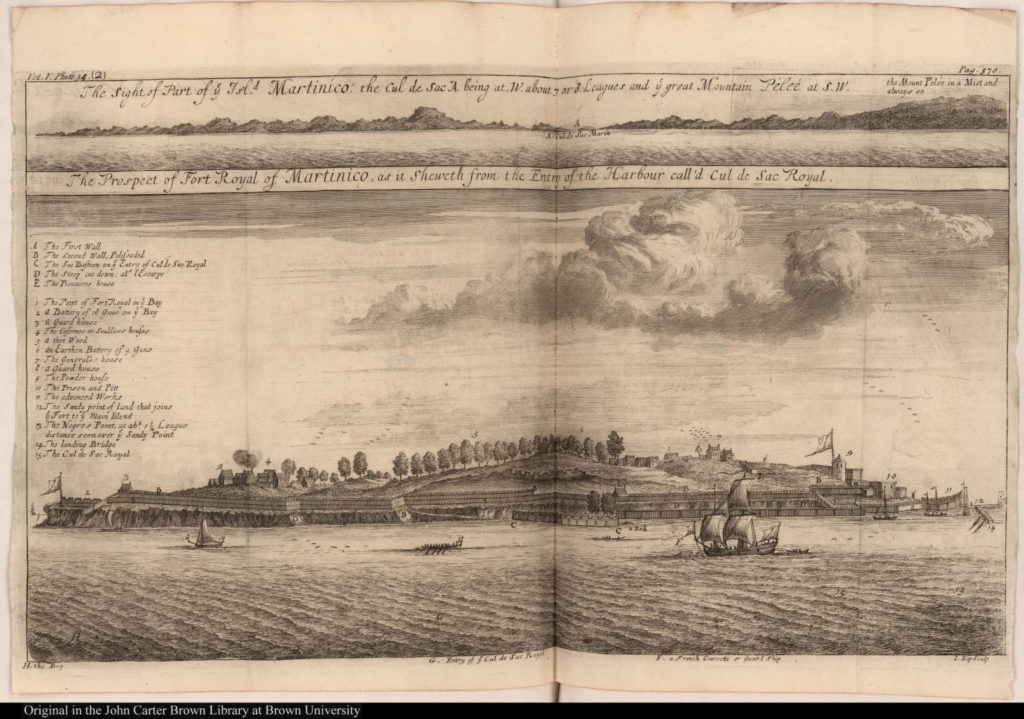

Early modern legal regimes were manifested materially – embodied, built, and performed –around key sites such as courtrooms and colonial prisons. But such sites were always being broken apart, renovated, and re-imagined. In the early 1740s, Jean Clavier, a bailiff in a Saint-Domingue admiralty court, was convicted and imprisoned on charges of illicit foreign commerce, a ubiquitous crime. In 1742, he escaped prison with two of his suspected accomplices. One administrator blamed “these frequent evasions [as] the effect of the bad state of the prisons of the whole colony.” It was nearly impossible to keep prisoners inside.[3] The prisons were continually falling down. Prisoners often just stepped over the rubble to escape. Clavier danced back and forth over these physical and legal boundaries as he managed court proceedings in his role as bailiff, and then became a target of such court proceedings.

Cases like Clavier’s help animate flat and often aspirational (rather than descriptive) sources about colonial legal spaces such as architectural plans for prisons and landscape drawings made by imperial competitors (Figure 5).[4] When we juxtapose these snapshots with Clavier’s zigzagging trajectory between court agent and escaped convict, prison cell and outside world, we can observe the permeability of material legal boundaries in practice and imagination.

First, we can look holistically at an overlapping, sometimes redundant colonial punitive matrix that included galley ships, exile, physical punishment, and incarceration. Descriptions of prison walls falling down, prison employees themselves being prosecuted – these paint a picture of a social and physical world that is constantly turning inside out as features responsible for enacting civil order become the means of its undoing. Rubble – entropy! – appears in Clavier’s case as the norm, with a built environment as always in-the-making, never made. Subjects could not be kept “inside” the bounds of legal and social ordering with prisons alone. So Clavier got a job as a bailiff, and got away with illicit trading, until he became the court’s target. And he stayed in prison until he could step over the fallen stones and leave.

Second, the practical challenges of constructing legality in a material form – complete with prison walls – help us think about when and where those legalities were most desired. Why were so many prison plans drafted, if not always built? And what did it mean when some, like Clavier’s prison, were crumbling? Such constant destruction, and inconsistent reconstruction, underscores the ephemeral, constantly changing environment itself via climate (tropical heat and humidity, hurricanes), poor construction methods (wood buildings, frequent urban fires), imperial warfare, and neglect.

Third, the careers of prison personnel – especially of those who found themselves on both sides of the law – help us to think constructively about socialordering in a world that was defined by the binary of bondage and freedom, but in practice contained a wide spectrum of statuses. Caribbean port towns sheltered a kaleidoscopic array of misfits and exiles: runaway slaves, pirates, and orphans; disinherited sons, murderers, illegitimate children, foreign militia leaders for hire. And of course, these categories could coincide and change rapidly, as in Clavier’s turn from bailiff to prisoner.

Legal Performances in the Boundary Lands: Violence, Objects, and Indigenous Claims in Colonial Mexico | Yanna Yannakakis

Boundary lands between Indigenous communities, marked by wooden crosses or piles of stones, were spaces of law in colonial Mexico. (Fig. 1) Porous by design, they were accessible to residents on either side for the collection of wood, medicinal plants, and other necessities. As the Indigenous population grew during the late seventeenth century, boundary lands became zones of contestation between Indigenous farmers looking to expand cultivation and pasture land. These pressures produced a patterned legal process for claiming land rooted in Indigenous and Spanish legal cultures.

A century-long dispute from Oaxaca provides an example. In December 1688, don Juan Garcia, a Mixe governor from the colonial district of Villa Alta confronted Jacinto Lopes, a Zapotec official from the district of Teotitlan-Mitla in a field between their communities. Lopes and his companions had entered the field with firearms and staffs of office, and had arrested and bound a group of Mixe farmers and officials. Garcia asked Lopes “how is it that you have done this, invaded with your staff of office in order to formalize a legal complaint?” He urged Lopes not to whip the men, but Lopes did so anyway. Next, Lopes collected the Mixe officials’ staffs – and the farmers’ clothes, machetes, a loom, a woolen mantle, axes, tools, and a pig — and returned with them to his village.

According to Spanish law, possession of land was defined by occupation and use. Lopes, with his staff and lash, countered the claim the Mixe farmers had made to the land by working it. His performance followed not only a Spanish legal logic, but also an Indigenous one. In the conquest of Oaxaca’s northern sierra, the Zapotecs allied with the Spanish, whereas the Mixe, their traditional enemies, resisted and kept their distance from colonial institutions. Zapotec litigants took advantage of their Spanish legal knowledge to dispossess Mixe communities. Lopes’ actions transformed a violent inter-ethnic conflict, which a century and a half prior would have been resolved through warfare, into a legal claim.

In 1798, Mixe authorities complained to the Spanish magistrate of Villa Alta that their Zapotec neighbors had burned their crops and hassled their villagers despite their possession of a legal title, confirmed by the ritualized laying of boundary markers. The Spanish magistrate of Villa Alta sent a complaint on their behalf to the Spanish magistrate of Teotitlan-Mitla, who promptly tore it up, perhaps hoping that the Zapotec authorities of his district would prevail. For the time being, the conflict would have to continue in the boundary lands rather than in the courts and on the written page.

Law and performative violence were constitutive elements of a single legal process and of legal culture in colonial Mexico. Violent performances in boundary lands featuring staffs, whips, and farming implements were just as important to Indigenous claims as more familiar manifestations of law like paper titles. Understanding colonial justice in rural, Indigenous settings requires attention to how law and a longue durée history of inter-indigenous relations patterned violence and object-centered performances in peripheral spaces.

[1] Archivo General de Indias, Mexico, 24, no. 6, 1598, f. 12.

[2] Quoted in Natalia Silva Prada, “Estrategias culturales en el tumulto de 1692 en la Ciudad de México: Aportes para la reconstrucción de la historia de la cultura política antigua,” Historia Mexicana 53, no. 1 (2003): 5-63.

[3] Archives nationales d’outre-mer (ANOM), COL E 83, Clavier, Jean.

[4] E.g. Archives nationales d’outre-mer (ANOM), Base Ulysse, 1731 Louisiana prison plan.