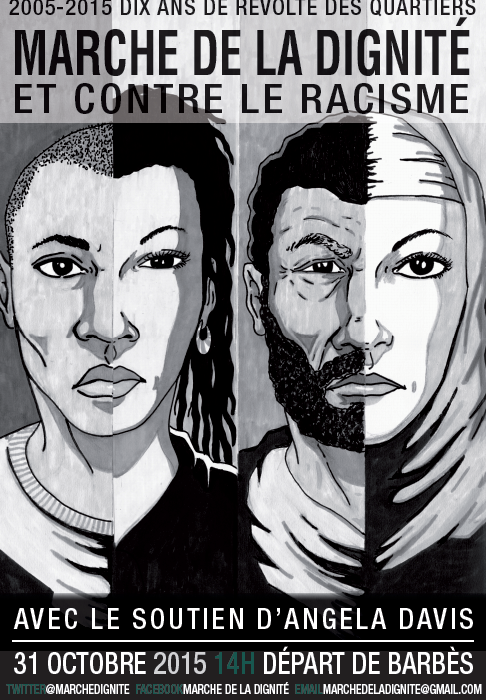

On October 31, 2015, the “March for dignity and against racism” (“Marche pour la dignité et contre le racisme”) was held in Paris to commemorate the uprisings of 2005 against police racism.[1] This is not the way U.S. protests against racism are framed. It is not that we never talk about dignity. Patrisse Cullors, one of the founders of Black Lives Matter, describes the movement as calling attention to “the ways in which Black lives are deprived of basic human rights and dignity.”[2] In Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court discussed the stigma attached to segregation of schoolchildren, as well as the right to attend schools freely with any of one’s neighbors, thus putting equality at least implicitly in terms of both dignity and liberty. Yet most “rights talk” in the U.S., and indeed the legal and constitutional framework of race discrimination law, has focused more on liberty than dignity.

What would it mean to recover an American tradition of dignity, and could it provide a firmer basis for civil rights again under siege? Histories of “white-supremacist counterattack,” as Rebecca Scott terms the backlash against racial equality during Reconstruction, feel particularly poignant at this moment.

“The right to be treated as one of the public without distinction of color.” Rebecca Scott’s excellent article on the concept of equal “public rights” begins with this definition. Delegates of color to the Louisiana state constitutional convention of 1867, led by Edouard Tinchant, drew on a vocabulary of public rights to characterize access to public spaces, in sharp contrast to the white supremacists’ talk of “social equality,” eventually memorialized in the Supreme Court’s Jim Crow jurisprudence in Plessy v. Ferguson and the Civil Rights Cases.

Dignity is arguably less central to the Anglo-American legal tradition than liberty. James Whitman, in several comparative articles about privacy and civility, argues that there are “two Western cultures of privacy: dignity versus liberty.” Europeans won’t talk about their salaries, but will take off their bikini tops; Americans hide their breasts but discuss money freely. Europeans protect privacy as part of a right to respect and personal dignity; Americans protect it as part of a right to freedom from intrusions by the state into one’s family or home. These differences, he argues, “grow out of much larger and much older differences over basic legal values, rooted in much larger and much older differences in social and political traditions.”[3]

The European tradition of dignity Whitman points to is concerned with honor and reputation. Whitman traces this tradition back to the early modern period, in which there was a “leveling-up” of norms of respect and honor to encompass everyone — even minorities, even prison inmates, rather than only nobles and royalty. Contemporary hate speech laws in France protect the honor of ordinary people the way dueling protected the honor of nobles.

Now if this culture of honor sounds a bit like the antebellum U.S. South, it’s no mistake. Unlike those in the North, white Southerners in particular understood their world in terms of honor, and they borrowed the tradition of dueling as well as the law of “insult.”[4] White Southerners sought to exclude “negroes,” including both slaves and free people of color from this world of honor.[5] The many provisions of law requiring people of color to give deference to whites, providing harsh punishments for insult to whites, designating appropriate clothing for people of color – and the horror Southern whites felt after the War in having to share roadways with people of color, their rush to criminalize vagrancy — all of these were about debasing and dishonoring Black people, making sure that they could not participate in the culture of honor.

All of this is to say that the demand for dignity was in many ways the most radical demand of all for people of color to make. And in order to make it as a legal claim, Louisiana free people of color drew on the Continental tradition of dignity.

Haiti was the inspiration for free and enslaved people of color across the Atlantic world. But many of the texts and people who inspired the public rights tradition came directly from Paris. From France came “a dose of quarante-huitard fervor and of hostility to aristocratic distinctions of ‘caste,’ coupled with a longstanding French concern with the legal protection of individual honor.” (Scott, p. ?) The debates over segregation in public transport from the first, Scott shows, implicated both personal honor and public respect. These ideas of honor and dignity followed a transnational trajectory through the bilingual forum of the New Orleans Tribune and the Revue du Monde Colonial Asiatique et Americain, which publicized the struggles of men of color for dignity on both sides of the Atlantic. By 1867, when Louisiana was placed under temporary military rule, about half the delegates to the constitutional convention were men of color, some only recently free and several with ties to the Tribune. Led by Edouard Tinchant, they demanded the inclusion of “public rights” in addition to “civil rights.” In 1869, a “civil rights bill” became law that included quite explicit protections for “public rights.”

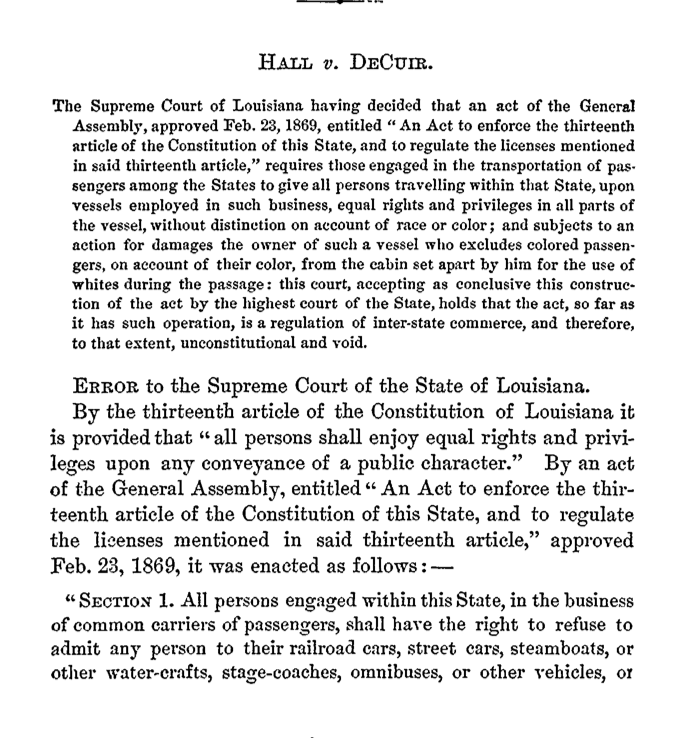

Scott ends her article with the fascinating story of Josephine Decuir, who used the 1868 Louisiana Constitution and the1869 legislation to challenge her treatment on a steamboat traveling up the Mississippi River, claiming that she “had not met a like indignity” in all her travels in the U.S. and France.

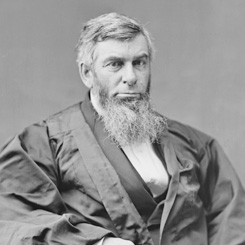

The case of Hall v. Decuir went all the way to the United States Supreme Court, where Chief Justice Waite opined that the Louisiana statute mandating public rights for people of color on public conveyances unacceptably burdened interstate commerce, given that the Mississippi River flowed through ten states.[6] (Of course, twenty years later, The Court inconsistently held in Louisville, New Orleans & Texas Railway Co. v. Mississippi, that a state statute requiring segregation in intrastate commerce did not run afoul of Congress’s commerce power…which wasn’t overturned for another half-century.)

Scott discusses a bit about the way Josephine Decuir embodied the ideal of dignity to which activists of color were laying claim. But here it is also useful to connect Decuir’s story, and the political and constitutional history of public rights as articulated by men of color, to the gendered tradition of challenges to railway segregation that Barbara Welke wrote about in Recasting American Liberty: Gender, Race, Law and The Railroad Revolution.[7] Josephine Decuir was one of a surprising number of women of color who challenged the law in the post-Civil War era. Welke’s work deftly paints the intersections between race, class and gender that met in the “ladies’ car,” where a select few women of color, women like Josephine Decuir, were able to maintain their dignity among white ladies and accompanying gentlemen – until Jim Crow pushed them out. Martha S. Jones’ magisterial new work, Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won The Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All, places Decuir into the context of a Black women’s political tradition of challenging inequality on behalf of all Black people, using all possible avenues.[8]

It would be fascinating to know more about Black women’s participation in the debates over public rights in which Edouard Tinchant and Jean-Charles Houzeau were involved, but also to think about the gendered meanings of honor and of dignity. For example, I found in my work on racial identity trials that performing white manhood was often expressed in terms of civic performances – sitting on a jury, mustering in the militia, voting – whereas for women, performing whiteness involved demonstrations of sexual honor.[9] Certainly the battle for the “ladies’ car” was all about sexual honor; it was physically unsafe to ride in the smoking car where one might be taken for a prostitute and vulnerable to assault. Perhaps dignity claims resonated even more deeply for women of color than for men; or at least, the challenges to women of color taking up space in public shaped the claims that both men and women of color brought to courts and legislatures.

Legal scholar Christopher Bracey has called for “a renewed commitment to seek dignity in contemporary race jurisprudence.”[10] Bracey notes that African American activists from the anti-slavery era onward have emphasized dignity concerns, and that the Supreme Court has at times recognized dignity values, although far less than those of liberty or equality. Bracey points to Lawrence v. Texas as a model for the affirmance of the dignity and essential humanity of gay people, that could be applied in the race context as well. Likewise, as mentioned at the outset, the Black Lives Matter movement has made dignity central to its framing of racial injustice in the United States and around the world. Thus, as we see in France today, dignity is a core value in certain legal cultures, but it has also been an important oppositional value in the U.S. As we are calling attention to the essential value and dignity of African American lives with the Black Lives Matter movement, perhaps we can draw on this rich transnational tradition that has crisscrossed the Atlantic but has deep roots here in the U.S. as well for the dignity of public rights.

At the same time, there are dangers in privileging dignity over liberty. Some forms of dignity require a European-style “leveling up” to an aristocratic ideal of honor. To level up in this way – the way Josephine Decuir demanded—involves a certain kind of performativity. It takes work. It’s not dignity inherent in humanity or in life, but requires the performance of a role. And here is where I think we find Josephine Decuir’s performance of respectability, of aristocracy, even, a little bit troubling. She performed high-class womanhood as a woman of color, but she did not necessarily demand that the steamer cabin be thrown open to all – only to those who successfully performed the role, and could pay. There are class dimensions to this dignity-based approach, as well as the materiality of basing rights claims on dignity. Critics of Brown, for example, pointed out the danger of making “stigma” the central injury of Jim Crow, rather than emphasizing the material deprivations of exclusion from public institutions. Katherine Franke points out that in same-sex marriage cases, gay activists have been arguing, and performing, respectability in order to win dignity-based rights, with consequences for the survival of a radical queer culture.[11] When enslaved women performed white womanhood in order to claim freedom, they subverted the system for individual rights, yet reinforced the hegemonic discourse of white honor and black debasement.[12] Can we base rights on dignity without such a dynamic? All of these musings relate to the presence of the past today. What difference does it make for the present to trace a tradition of public rights to ancient Rome, to eighteenth-century France, to nineteenth-century Louisiana? Can we take “dignity” away from its aristocratic roots – as, in the 1980s, advocates of “civic republicanism” as an alternative to liberalism tried to cut it off from its roots in propertied white manhood?[13] As a historian teaching in a law school, these are questions I’m deeply interested in, but I don’t know that we all will agree on the answers.

[1] https://www.lejdd.fr/Societe/Contre-le-racisme-une-marche-de-la-dignite-dans-les-rues-de-Paris-757661.

[2] See Patrisse Cullors, “Black Lives Matter,” at https://patrissecullors.com/organzier/ (last accessed 12/08/20).

[3] James Q. Whitman, “Two Western Cultures of Privacy: Dignity versus Liberty,” Yale Law Journal 113 (2003-2004): 1160.

[4] See Bertram Wyatt-Brown, Southern Honor: Ethics and Behavior in The Old South (Oxford, 1982); Kenneth S. Greenberg, Honor and Slavery (Princeton, 1996).

[5] See Ariela Gross, Double Character: Slavery and Mastery in The Antebellum Southern Courtroom (Princeton, 2000), 47-71.

[6] Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U.S. 485 (1877).

[7] Barbara Welke, Recasting American Liberty: Gender, Race, Law, and The Railroad Revolution, 1865-1920 (Cambridge, 2001).

[8] Martha S. Jones, Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won The Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All (Basic Books, 2020).

[9] Ariela Gross, What Blood Won’t Tell: A History of Race on Trial in America (2008), 48-72.

[10] Christopher A. Bracey, Dignity in Race Jurisprudence, U. Pa. J. Const. L. 7 (2005):669.

[11] Katherine Franke, “Dignity Could Be Dangerous at The Supreme Court,” Gender & Sexuality Law Blog, June 26, 2015, at http://blogs.law.columbia.edu/genderandsexualitylawblog/2015/06/26/dignity-could-be-dangerous-at-the-supreme-court/ (last accessed on 12/08/2020).

[12] Gross, What Blood Won’t Tell.

[13] See Laura Kalman, The Strange Career of Legal Liberalism (Yale, 1996); Nomi Maya Stolzenberg, A Book of Laughter and Forgetting: Kalman’s “Strange Career” and the Marketing of Civic Republicanism, Harvard L. Rev. 111 (1998): 1025.

winner of the James Willard Hurst Prize from the Law and Society Association, winner of the Lillian Smith Award for the best book on the U.S. South and the struggle for racial justice, the American Political Science Association’s Best Book on Race, Ethnicity, and Politics, and a Choice Outstanding Academic Title.

winner of the James Willard Hurst Prize from the Law and Society Association, winner of the Lillian Smith Award for the best book on the U.S. South and the struggle for racial justice, the American Political Science Association’s Best Book on Race, Ethnicity, and Politics, and a Choice Outstanding Academic Title.