In 1994, William J. Novak published, The People’s Welfare: Law & Regulation in Nineteenth-Century America. The book was quickly hailed as a brilliant account of the many ways that American lawmakers—from common law judges to local legislators—regulated antebellum American economy and society. With his panoramic view of the myriad types of nineteenth-century government activity, Novak debunked the libertarian myth of a so-called past “golden age” of U.S. laissez-faire law and political economy.

At the end of that award-winning monograph, Novak gestured toward a sequel project – one that would explore the shift from the antebellum localism and self-governance of a “well-regulated society” to the more centralized, rationality of a modern state. New Democracy is that long awaited sequel. And it delivers on nearly all fronts.

In periodization, New Democracy picks up where The People’s Welfare left off, chronicling the interventionist ideas and efforts of jurists, reformers, and lawmakers from the end of the Civil War to the dawn of the New Deal. With a particular focus on the Progressive Era, Novak identifies and analyzes the many antecedents to New Deal state-building, thus, challenging the notion of Franklin D. Roosevelt as the exclusive political pioneer of progressive reform.

The two books have several similarities. Like it’s prequel, New Democracy focusses mainly on what the state did. Although the book explores the ideas and theories underpinning Progressive Era social democracy, its main category of analysis is the details of state action by state actors. In this sense, the book takes seriously institutionalist economist John R. Common’s definition of the state as “what its officials do.”[1] And what they did is spelled out in great detail, including through Novak’s enduring and persistent penchant for long and descriptive lists of the items regulated and managed by government entities.

New Democracy also continues Novak’s career long agenda of exposing, as he puts it, “persistent and dangerous fallacies about an original American historical tradition defined primarily by transcendent precommitments to private individual rights, formalistic constitutional limitations, and laissez faire political economy.”[2] Indeed, the two books together join a growing chorus of scholarship by historians and historically-oriented social scientists that not only challenges conventional accounts of the so-called, anti-statist “Lochner Era” of U.S. jurisprudence, but also the entire notion of a weak or laggard American state.[3]

New Democracy also differs from its prequel in at least one fundamental way. The People’s Welfare was mainly a synchronic analysis, a snapshot of antebellum law and society and its ubiquitous rules and regulations. By contrast, New Democracy, or at least a majority of the case studies within the book, relies on a more diachronic perspective, showing change over time, moving from nineteenth-century traditions of “local self-government” to a more modern approach of “positive statecraft, social legislation, economic regulation, and public administration.”[4] In many ways, the latter perspective is more persuasive, particularly in the early chapter about citizenship, in demonstrating the dramatic transformation that is at the heart of New Democracy.

Together, the two books make significant contributions to the scholarly literature and current political discourse about American history. Methodologically, New Democracy as Novak describes it is “a work of modern sociolegal history,” by which he means that his analysis goes beyond “sclerotic constitutional conceptions of the great cases, high courts, herculean judges limiting law’s reach” to explore law’s “forceful creative efficacy.”[5] In this way, Novak joins many other sociolegal historians from Mike Grossberg to Dirk Hartog to Laura Edwards and Barbara Welke in chronicling the quotidian impact of law, legal institutions, and legal processes.

The new book makes several contributions to other historiography. By detailing the creative aspects of public law, New Democracy advances many of the objectives of the New, New Political History. Novak moves beyond the traditional right/left divide to show how there was apparent bipartisan support for turn-of-the-century state building – support for a more robust sense of egalitarian forms of participatory democracy.[6]

New Democracy also follows the New, New Political History’s trend of decentering the U.S. nation-state by looking beyond and below the U.S. federal government. In the process of exploring the precursors of New Deal liberalism, Novak places U.S. reforms in a broader context; more specifically in a transatlantic dialogue similar to the work of Dan Rodgers and Jim Kloppenberg. He also details the many reforms taking place at the subnational level, as state, county, and local officials experimented with their own forms of substantive democratic reforms.

Although Novak describes his project as a “modern sociolegal history,” at its heart New Democracy is also a major contribution to American intellectual history. It is a work about the history of ideas, though not exclusively about ideas. As the richly detailed endnotes illustrate, Novak is engaging with some of the leading works of Progressive-Era intellectual history, from Morton White to Thomas Haskell to Dorothy Ross and Ed Purcell. Likewise, the book evokes some of the leading modern theorists of democracy—from Hanna Arendt to Jurgen Habermas— to show the fragile and delicate nature of democratic decision making.

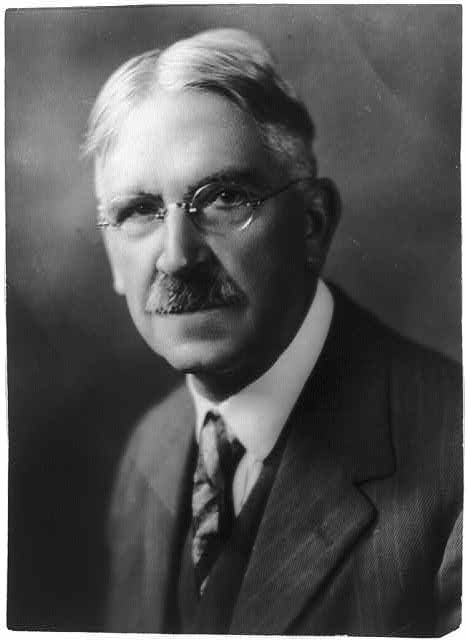

Indeed, many of New Democracy’s leading protagonists include not only well-known jurists such as Louis D. Brandeis and Felix Frankfurter, but also some of the prominent social scientists and reformers of the time period, from Frank Goodnow to Ernst Freund to Jane Adams and Edith Abbot. And, of course, the most serious and sophisticated twentieth-century voice for a new democracy: John Dewey.

In many ways, John Dewey is the patron saint of New Democracy. Dewey, as Robert Westbrook has shown with his superb biography, was not just a philosopher or social theorist, he was also a political activist—an activist for a new liberalism and a new type of American participatory democracy. For Dewey, “democracy was a way of life.” [7] Deweyan democracy, like Novak’s interpretation of the zeitgeist, rested on a relentless faith in the capacity of human beings for intelligent judgement under the right conditions. And it was up to the state, as Novak shows, to provide those conditions.

Despite its comprehensive purview, New Democracy is not without its surprises or missed opportunities. Given the time period, for example, it is surprising that there is not more attention paid to World War I and its role in American political and economic development. The Great War, after all, was the crucial world-historical event and national crisis between Reconstruction and the Great Depression – and one that solidified the United States’ position as a rising, global hegemon.

This omission is equally surprising because of Novak’s sophisticated engagement with the broader historiography and historical social science literature. Charles Tilly noted long ago that “States make war and war makes states.”[8] Similarly, Robert Cuff in his landmark study of WWI and the War Industries Board famously observed that “an administrative army marched into Washington well before a military force sailed overseas.”[9] And many other historians, such as James Sparrow and Mark Wilson, have documented the critical role of international conflicts in the growth of U.S. public power and authority.

Yet WWI only makes occasional appearances in the New Democracy: in a discussion of conscription, the creation of the Food Administration, and the role of the military police in pushing model social legislation during the war. One could easily have imagined a Novakian list of all the federal agencies created during the war, from the War Trade Board, to the Committee on Public Information, to the Food Administration, to the Fuel Administration, and the Railroad Administration to name just a few.

In the wake of the war, even Dewey recognized the “ratchet effect” of the conflict when he wrote: “The immediate emergency has in a short time brought into existence agencies for executing the supremacy of the public and social interest over the private and possessive interest. … In this sense, no matter how many among the special agencies for public control decay with the disappearance of war stress, the movement will never go backward.”[10]

Finally, New Democracy makes such a compelling and totalizing case for the emergence and dominance of this new form of egalitarian, democratic governance that one is left to wonder about possible counter narratives, such as the potential excesses of democracy. What is one to make of Tocqueville’s concerns about the “tyranny of the majority,” particularly during the Red Scare of the 1920s? And what about other minority rights, as historian Kyle G. Volk has demonstrated, that were in peril when populist fervor and mainstream public opinion pushed for greater conformity in an earlier period of American history.[11] Likewise, one wonders about the hinderances of human hubris that are part and parcel of democratic statecraft, or what Willard Hurst referred to as the “drift and default” of lawmaking in his own historical sociology.[12] These closing questions illustrate not so much the missing elements in Novak’s narrative, as they do the provocative queries that the monograph elicits. Indeed, scholars and educated readers will be grappling with Novak’s reinterpretation of turn of the twentieth century American law and political economy for many years to come. Perhaps Novak’s next project will address some of these pertinent inquiries.

[1] John R. Commons, The Legal Foundations of Capitalism (New York: Macmillan, 1924), 122. Of course, the legal realist Karly Llewelyn famously echoed Commons when he proclaimed that “what official do about disputes is, to my mind, the law itself.” Karly Llewellyn, The Bramble Bush (New York: Oceana, 1930), 12.

[2] William J. Novak, New Democracy: The Creation of the Modern American State (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2022), 3.

[3] See, for example, Brian Balogh, A Government Out of Sight: The Mystery of National Authority in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009); Gautham Rao, National Duties: Custom Houses and the Making of the American State (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016); Christopher Howard, The Hidden Welfare State: Tax Expenditures and Social Policy in the United States (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997); Joanne L. Grisinger, The Unwieldy American State: Administrative Politics Since the New Deal (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012); Suzanne Mettler, The Submerged State: How Invisible Government Policies Undermine American Democracy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011).

[4] Novak, New Democracy, 1.

[5] Ibid., 14.

[6] Although scholars are regularly claiming the start of a new era of political historiography, the latest trend is accurately captured by the essays in Shaped by the State: Toward A New Political History of the Twentieth Century, eds. Brent Cebul, Lilly Geismer, and Mason B. Williams (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019).

[7] Robert B. Westbrook, John Dewey and American Democracy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991).

[8] Charles Tilly, “War Making and State Making as Organized Crime,” in Bringing the State Back In, eds. Peter B. Evans, Dietrich Rueschemeyer and Theda Skocpol, eds. (New York: Cambridge University Press); Charles Tilly, Coercion, Capital, and European States: AD 990-1990 (Cambridge, MA: Basil Blackwell, 1990).

[9] Robert D. Cuff, The War Industries Board: Business-Government Relations during World War I (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973), 1.

[10] John Dewey, “What are We Fighting For?” in The Collected Works of John Dewey v. 11; 1918-19 ed. Jo Ann Boydston (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1982), 103.

[11] Kyle G. Volk, Moral Minorities and the Making of American Democracy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

[12] James Willard Hurst, Law and the Conditions of Freedom in the Nineteenth-Century United States (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1956), 53.