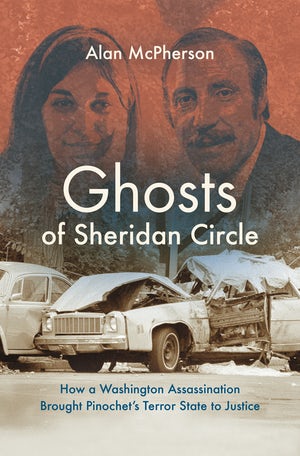

In 2019, Professor Alan McPherson published The Ghosts of Sheridan Square: How a Washington Assassination Brought Pinochet’s Terror State to Justice (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019), which recounts the history of the 1976 murder of Orlando Letelier, who served as the Chilean Ambassador to the United States under Salvatore Allende. Letelier’s widow believed Augusto Pinochet was responsible for the murder but the United States was hesitant to interpose itself against Pinochet, a purported ally. The book documents how the Letelier family’s legal struggle would continue for decades. Professor McPherson also has an article about the Letelier family’s civil suits against the Pinochet government forthcoming in Law and History Review. Professor McPherson was kind enough to spend some time discussing his recent work with The Docket.

The Docket [TD]: To begin, can you summarize the legal efforts that followed the assassination of Letelier and Moffitt in 1976?

Alan McPherson [AM]: Most of the legal efforts–which are not the main topic of my article but they are of my book, Ghosts of Sheridan Circle–were criminal trials. When the Justice Department identified the co-conspirators of the car bombing in Sheridan Circle, Washington, DC, they indicted many of them in U.S. criminal courts. These included Michael Townley, an American-Chilean explosives expert, five Cuban-Americans, and eventually three Chileans. Only Townley and three Cuban-Americans were tried in the 1970s, and only Townley served time. The two other Cuban-Americans were caught in the 1990s and served long sentences. One of the three Chileans defected to the United States in 1987 and was convicted. The two others were tried in Chile in the 1990s and convicted.

My article in LHR, however, focuses on civil trials in the United States. These were filed by the surviving family members of Orlando Letelier and Ronni Moffitt against the Chilean government itself, accusing it of being a party to the conspiracy and suing for damages under the newly-passed Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA). The suit claimed that FSIA contained a loophole allowing U.S. citizens to sue foreign governments for damages resulting from non-commercial torts. One judge ordered Chile to pay damages, but when the plaintiffs sued to attach Chilean property in the United States–in this case, a government-controlled airliner–another judge denied their claim.

TD: You make a pointed argument that unsuccessful civil lawsuits by Letelier and Moffit’s families actually improved the usefulness of civil justice for punishing state terrorism (you make a parallel argument that legal scholars’ dismissal of the Letelier cases misses this point). Can you say more about this?

AM: The Letelier cases were indeed meaningful in what they inspired. They were the first to make the argument that FSIA could be applied to non-commercial torts, which might include acts of terrorism. They therefore opened the door to families of U.S. victims pursuing justice against foreign governments who committed terrorist acts in the United States. In the 1980s, at least two other cases pursued that logic. Most important, the 1996 Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, aiming to clarify these rights, included an explicit exception of immunity for acts of terrorism. The historical record shows that Congressional deliberations over these issues were largely influenced by the Sheridan Circle assassination.

TD: Your work in LHR is part of a broader book project, one which pushes beyond many Americans’ interest in a discrete terror act on US soil to the longer history of the Chilean right’s rise to power and relationship to Washington. How do the killings of Letelier and Moffitt look differently through this lens?

AM: The assassination reveals the hubris behind Operation Condor and the U.S. enabling of it. Operation Condor was a conspiracy that ran from about 1975 to 1983 between the murderous militaries and dictatorships of the Southern Cone of South America, who agreed to help hunt down each other’s political opponents. The original intent was for Condor to remain within South America, but the Letelier assassination was an example of how it spilled over into non-Condor countries. Yet it’s indicative that the Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford governments, both of whose foreign policies were directed by Henry Kissinger, were considered so friendly and “pro-Condor” by the Pinochet regime that it likely thought it could pull off a car bombing in the U.S. capital and not suffer any retaliation. In the weeks before the assassination, Pinochet hinted to Kissinger that Letelier was among the thorns in his side that he wanted removed. Kissinger said nothing. In fact, he rescinded an order to his ambassadors to warn South Americans against plotting Condor-like assassinations.

TD: Broader context of historical understanding of force and state violence in international law? What can hold states accountable in their international actions? (McPherson suggests a long struggle pitting fascism against human rights in Latin American political culture, linked directly to German immigrants)

AM: The Letelier-Moffitt murder is indeed a window into a larger confrontation in the Americas between the forces of fascism and the proponents of human rights, one that continues to this day from the United States to Brazil. The Pinochet government was not pro-Nazi, but proponents of fascism saw in Pinochet their champion, and Pinochet was explicitly admiring of Spanish dictator Francisco Franco. Orlando Letelier often called junta leaders “fascists,” and he found plenty of evidence in their repression and their economic model.

The natural opponent of fascism is human rights–a belief system that posits universal natural decency rather than hierarchy as a way to organize society. Ronni Moffitt and her husband Michael Moffitt, who survived the car bomb from the back seat, were two militants in the peaceful struggle for human rights, which reached a peak in the mid-1970s. Orlando Letelier, as a think-tank activist, was savvy enough to understand that this–rather than socialism–was where he could find the most allies among U.S. activists and members of Congress.

Besides helping to pass laws in the U.S. Congress, human rights forces have also used the courts, whether in the United States or abroad. Just as the forces of fascism considered Operation Condor to be immune to issues of sovereignty, so human rights proponents–with much more admirable goals, it must be added–have aimed to weaken state sovereignty in favor of an international legal regime that could challenge sovereign actors who commit crimes against humanity.

TD: The Letelier-Moffitt killings may appear relevant in light of recent allegations that Washington Post journalist Jamal K. was murdered by Saudi security forces. One key difference would seem to be that the 1996 AEDPA expands FSIA to cover state terror acts outside the US, but only in cases where they are committed by “state sponsors of terror”—has the 1996 AEDPA reverted the question of sovereign immunity to the (political) State Department?

AM: That’s correct. Part of the motivation for FSIA was to take decisions over whether to pursue foreign governments in court out of the political hands of the State Department and into those judges. Since 1996, however, to be indicted, a government must be designated a “state sponsor of terror,” and only the Secretary of State curates that list. So countries such as Cuba, Libya, and North Korea have been put on or taken off the list more as punishment or reward for cooperating with the U.S. government rather than as a reflection of their sponsorship of terrorism. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, as it may encourage some governments to moderate their repression. And it’s also not clear that judges are less political than secretaries of state. In the Khashoggi case, therefore, AEDPA could not be invoked because Saudi Arabia is not on the State Department’s list. And in any case, Saudi Arabia is a far more redoubtable ally than Chile ever was.