In his 2019 memoir, The Making of a Justice, John Paul Stevens playfully recounted seating arrangements for conferences, the regular meetings of the justices to discuss Supreme Court matters and cases, during his first few terms. Seated to the right of Bill Brennan and to the left of Bill Rehnquist when his turn to speak arrived, Stevens frequently began by saying “’I agree with Bill’ – my colleagues then had to wait for an explanation of which of my friends I was joining.’“

Clever, no doubt, but not always true as demonstrated during the October 1975 (OT 1975) term, his first on the Court. When he and his fellow justices heard National League of Cities v. Usery, a state challenge to the Fair Labor Standards Act, which extended federal minimum wage and hour protections to state and municipal workers, Stevens dissented from Rehnquist’s majority opinion but nor could he sign on to Brennan’s dissent. The reason Stevens, who earned a reputation as a legal maverick on the Court, diverged from both Bills can be found in the John Paul Stevens Papers which recently opened to the public and span his first nine terms on the Supreme Court from October 1975 to July 1984 (October 1975 through October 1983 terms) . The John Paul Stevens Papers add further context to both one of the most important institutions in American life and one of its longest serving justices.

In his case history of the National League of Cities, William Brennan described Rehnquist’s majority opinion as “so devoid of logic and reasoning that it sparked a faint glimmer of hope that he might not hold the Court.” As a result, Brennan drafted a stinging dissent that, according to Brennan, Stevens found “devastating.” Representing his own views on the case in his conference notes, Stevens wrote cryptically, “Smoke from the capital,” a possible reference to the kind of legislative frustration Rehnquist’s opinion might spark among some members of Congress. However, Brennan’s dissent proved too provocative for the newly appointed justice. “Although I agree with your analysis and think you have written an excellent and persuasive opinion,” Stevens wrote in a memo to Brennan, “I am reluctant to join it only because I am not sure that I completely share some of your extremely strong criticism of other decisions of the Court.” Stevens dissented but demurred from joining Brennan’s.

As he notes in his memoir, in hindsight, Stevens sided with Brennan and agreed that “his characterization of Bill Rehnquist’s majority opinion was fair,” but that as the newest member of the Court, he felt it pushed the envelope too far. Indeed, Rehnquist’s opinion was overturned several years later in Garcia v. San Antonio Metropolitan Transit Authority (OT 1984). Though Stevens’s papers currently do not extend past OT 1983, those of Harry A. Blackmun, William J. Brennan, Byron White, Thurgood Marshall, are available to researchers in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division and provide alternative vantage points from which to observe Stevens’s judicial evolution.

Stevens authored several significant dissents and opinions during his first nine terms. Many are documented in his papers and offer insight into not only his own jurisprudence but those of his fellow justices. Drafts of opinions and dissents, including some handwritten ones, memoranda such as the one he sent to Brennan in National League of Cities, conference notes, docket sheets, and other court related materials abound in the collection. The opinion files, organized largely according to the arrangement by Stevens’s staff, are not typical of most Supreme Court papers. Although organized by court term, they are divided into two groups: court circulations and Stevens’s assignments. Cases filed in the court circulations consist mainly of cases in which other justices wrote the deciding opinion for the Court. If Stevens wrote for a case, the case is filed under Stevens’s assignments.

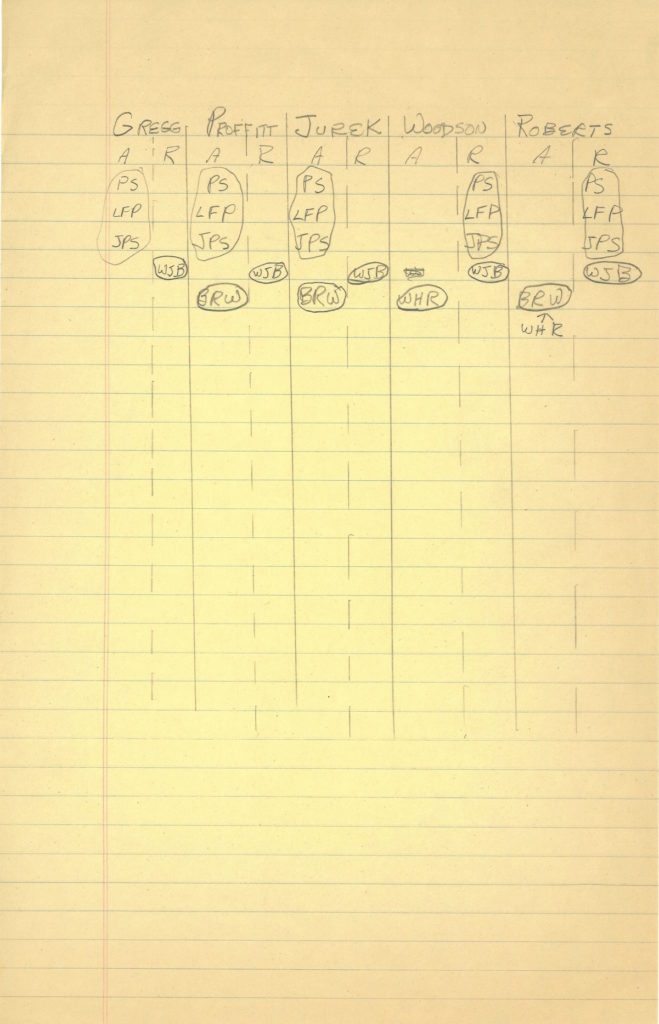

That same term, the Court was inundated with death penalty cases. At a January 1975 meeting the justices agreed to hear five arguments relating to state laws extending capital punishment in North Carolina (Woodson), Louisiana (Roberts), Texas (Jurek), Florida (Proffitt), and Georgia (Gregg). Along with Justices Potter Stewart and Lewis Powell, Stevens authored what emerged as the lead opinion in Gregg v. Georgia.

The cases were not without internal controversy. At conference, Chief Justice Warren Burger attempted to hand all five cases to Justice Byron White as a means to produce one overarching, controlling opinion. As Stevens’s vote tally attests, a majority of the Court had voted to strike down the North Carolina law, hence making Burger’s assignment impossible. Stevens’s tally omits Justice Thurgood Marshall, although the reason why is not readily apparent. Marshall along with Brennan rejected the constitutionality of capital punishment outright, so perhaps his votes being a forgone conclusion were not included. Yet, the same could be said of Brennan and his votes are listed.

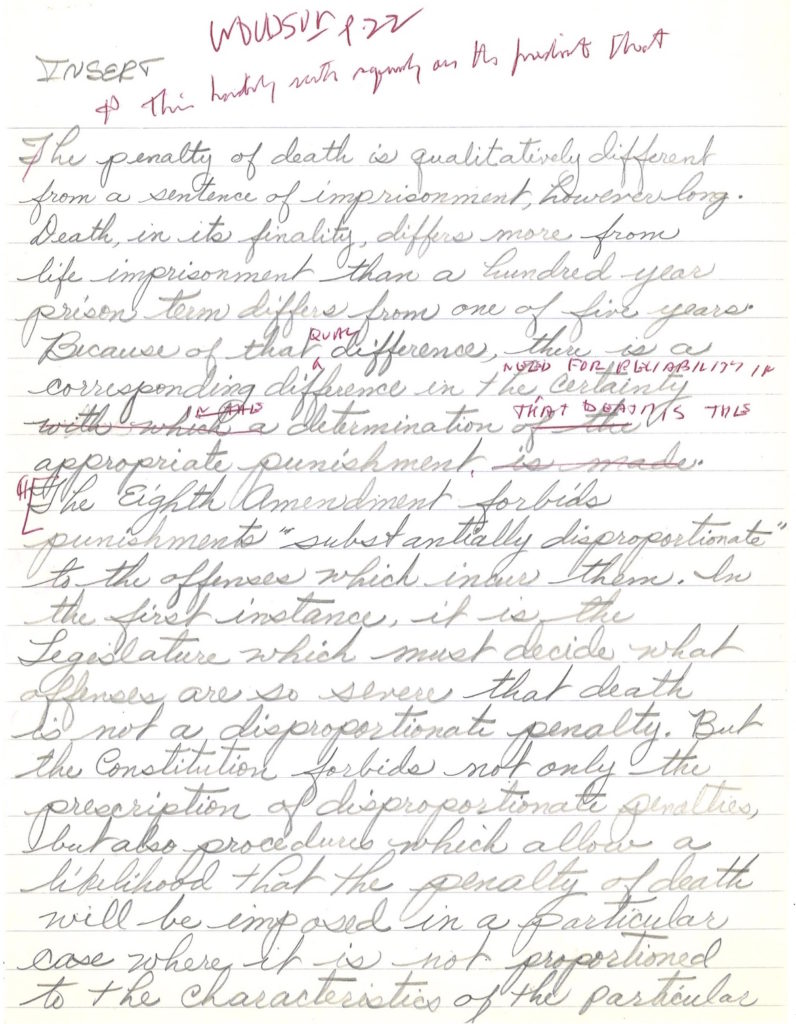

According to Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong’s account in The Brethren, a majority of the justices voted to strike down Woodson in part due to evidence of racial discrimination in sentencing, Stevens’s insertion to page 22 of the Woodson opinion, written by his clerk at the time with the justice’s annotations, is included in the case file and reflects the gravity of the issue. “Death, in its finality, differs more from life imprisonment than an hundred year prison term differs from one of five years. Because of that qual[atative] difference there is a corresponding difference in the need for reliability in the certainty that death is the appropriate punishment.”

Powell, Stevens, and Stewart managed to gather plurality rulings for each case with Gregg serving as the lead opinion. In Gregg, “the Troika” as Woodward and Armstrong dubbed Stewart, Powell and Stevens, granted the constitutionality of the death penalty but cautioned that “unbridled jury discretion produces arbitrary results” allowing instead for “a bifurcated trial with individualized consideration of both aggravating and mitigating circumstances …” note Linda Greehouse and Matthew J. Graetz in their history of the Burger Court. The co-written opinions caused some amount of “confusion in the media, and among lawyers and judges as to who had written the case,” notes a memorandum in Stevens’s papers. Reporters initially could not discern who had authored each opinion leading to a change in the slip opinion that clearly stated its authorship.

One final note on the death penalty cases, by Stevens’s account, he had delegated the statement of facts for the death penalty cases to one of his clerks. In hindsight, he deemed this decision to have been a mistake, since he believed that his vote to affirm in the Texas case, Jurek, had been cast incorrectly. “I should then have realized that a jury instruction required by the Texas statute had the practical consequence of converting what at first blush appeared to be a valid discretionary sentencing scheme into an invalid mandatory scheme.” It remained one of his few stated regrets from his time on the Court and in his final years on the Court, Stevens repudiated capital punishment notably in Baze v. Rees (OT 2007).

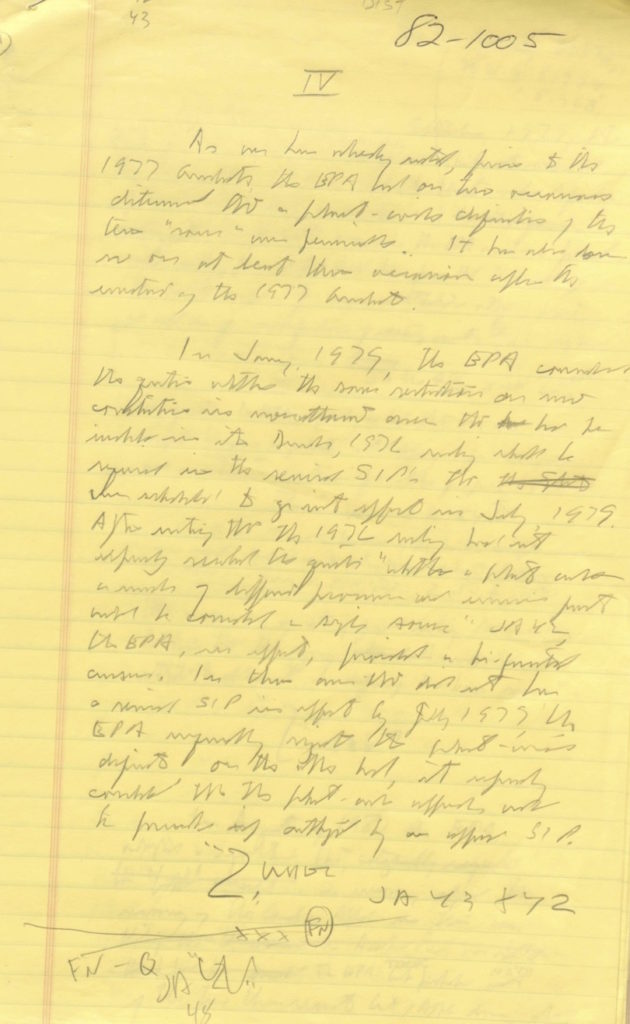

For every regret, however, Stevens had plenty of triumphs. His opinion in Chevron v. National Resources Defense Council (OT 1983) remains his most cited case and a landmark ruling in administrative law as it “established the proposition that Congress may delegate its power to make policy decisions to agencies created to administer its programs,” Stevens wrote in 2019. His papers include his handwritten drafts of the opinion enabling researchers to track his thinking in the case.

According to Stevens, however, one of the opinions for which he felt the most pride was NAACP. v. Claiborne Hardware Company. (OT 1981). Though Marshall recused himself and Rehnquist concurred, the opinion otherwise was unanimous and remains germane to the current moment. From 1966 to 1972, the NAACP and activists in Claiborne County Mississippi had boycotted several white merchants as a means to get them to sign a petition calling for “the desegregation of all public schools and public facilities, the hiring of black policemen, public improvements in black residential areas, selection of blacks for jury duty, integration of bus stations … and an end to verbal abuse by law enforcement officers.” The merchants sued and won a $1,250,699 award against 92 of the boycott’s participants. The NAACP challenged the ruling and the Supreme Court accepted the appeal.

The crux of the case rested on the fact that evidence suggested some organizers and supporters of the boycott had threatened or acted violently against persons refusing to support the protest, largely against African-American residents who shopped in white owned establishments. According to a Stevens memorandum, which excerpted portions of the county sheriff’s testimony, one of the boycott’s leaders, Charles Evers, had said in a 1966 speech, “If you break the boycott your own people will break your necks.” However, the sheriff also acknowledged that the boycott extended over several years “off and on from April 1966 to 1970” and that in the final few “[m]ost of the time it was teenagers and at the last it was little bitty fellows, as young as about six years old,” who worked the picket lines.

In writing the decision, the correspondence between Justice Lewis Powell and Stevens containing Powell’s various concerns illustrate how opinions are shaped but also reveal how Powell felt about the state of political discourse more broadly in 1982. Powell did not view Evers’s comments benignly. “Perhaps some of my concern derives from the increasingly violent age in which we are living,” he wrote Stevens. “Legitimate First Amendment rights must be safeguarded without encouraging incitement to violence.”

While Powell agreed with Stevens generally, he found some of his colleague’s language “unnecessarily broad.” Powell’s letter then focused on three pages of Steven’s opinion where he believed the ruling would make it “extremely difficult to hold anyone responsible for the consequences of incitement or violence” including questions of causation and incitement, the extent to which Evers’s statement authorized, ratified or directly threatened acts of violence, and the culpability of the NAACP and Evers. Stevens’s annotations appear in the margins identifying page numbers, affirmation of Powell’s trepidations, and comments such as “agree to omit.”

Even amidst these reservations, Powell acknowledged that proving actual damages in such a case “will be near impossible” since “no one can be entirely sure as to what damage was caused by what specific action … incitement is more appropriate where violence occurs within a reasonable time.” Powell ended on a note of pessimism, “it does seem to me that world order is showing signs of unraveling. The difference between the essentially peaceful picketing involved in this case and the mindless mobs in the street will not always be easy to define.” He worried further that in the future, First Amendment cases cited by Stevens in the opinion might “in a different era … be relied upon to justify even serious threats to the rule of law.”

In the end, Stevens addressed Powell’s concerns by moderating some of the language that his colleague had viewed as too broad. While Evers’s speech trafficked in “emotionally charged rhetoric,” wrote Stevens in the final opinion, it “did not transcend the bounds of protected speech.” Going further, Stevens noted advocates like Evers, “must be free to stimulate his audience with spontaneous and emotional appeals for unity and action in common cause.” In regard to alleged violence pertaining to the boycott, he characterized the Mississippi Supreme Court’s findings as “ambiguous.” Adding that “massive and prolonged effort[s] to change the social, political, and economic structure of a local environment cannot be characterized as a violent conspiracy simply by reference to the ephemeral consequences of relatively few violent acts.”

In her 2020 remembrance of Justice Stevens for the Michigan Law Review, Linda Greenhouse noted that despite over three decades on the Court, he “was more celebrated in retirement and after his death,” than during his tenure. Yet the very things that moved him, “are missing now in our public life: the power of facts, of logic, and of approaching each problem with an open mind, ready to be persuaded or, if his luck was running to persuade.” Now open to the public, the John Paul Stevens Papers provide insights into the evolving jurisprudence of one the nation’s longest serving justices and leading thinkers.