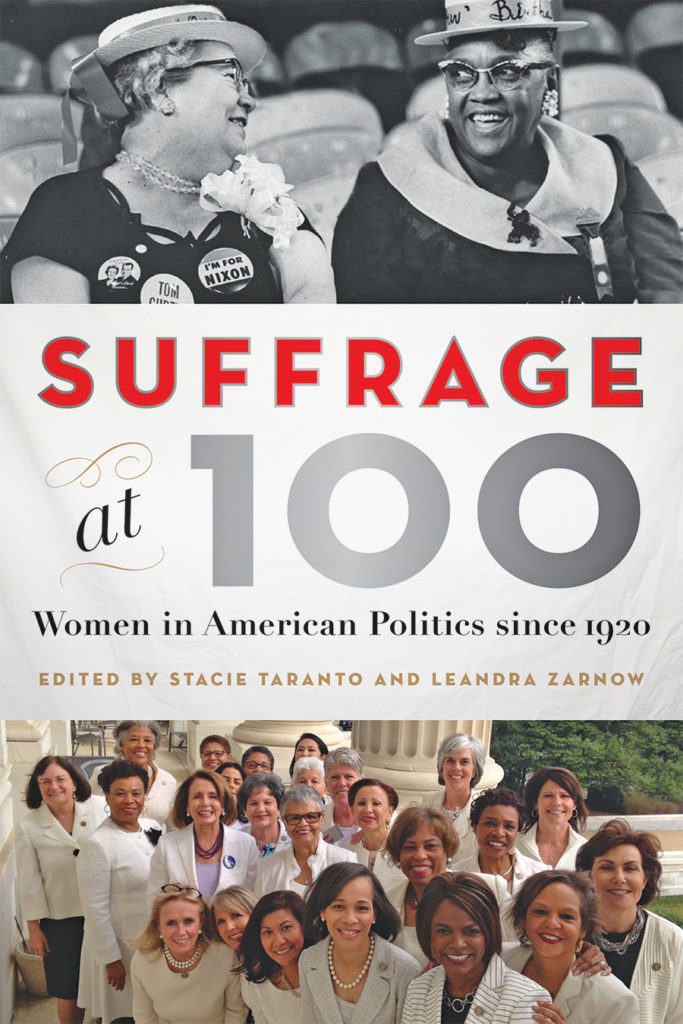

Stacie Taranto and Leandra Zarnow, ed., Suffrage at 100: Women in American Politics Since 1920 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2020).

Review by Cathleen D. Cahill, Penn State University.

This exciting collection is well-timed and well-done. It is part of the rich body of scholarship inspired by the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment as scholars have assessed the meaning and impact of that Constitutional change. While much of that conversation has focused on the nineteenth century and the decades around 1920, Suffrage at 100 offers a broader overview of the century that followed ratification, concluding with the election of 2018.

While the suffrage centennial is the reason for the collection, only one–Liette Gidlow’s excellent analysis of Black southern women’s disenfranchisement after 1920–explicitly focuses on voting. The others essays explore women’s political engagement as candidates, elected representatives, grass roots activists, and civil servants.

Taranto’s and Zarnow’s introductory essay provides an overview of the century based on a somewhat schematic, but effective framework. They assert that women were (and continues to be) judged upon the political ideal of a straight white man. In response, women often used maternalist arguments claiming women’s role as mothers to justify their engagement in politics. How this played out is a theme in a number of pieces.

The twenty essays that follow are snappy and in several cases I found myself enjoying the read so much I started a new essay when I had meant to take a break. Also, I appreciated that the notes were included at the end of each piece. They are divided into three chronological sections: the 1920s to the 1950s, the 1960s to 1980s, and 1990s to 2010s though the later primarily focuses on the years since 2008. They lend themselves to being read in order, but also admirably stand alone.

The first section is the largest with nine essays. Claire Delahaye’s begins by introducing a running theme — the politics of suffrage history. Delahaye argues that the National Women’s Party’s historical commemorations were claims to authority in the face of division and shrinking membership after 1920. A later essay by Ana Stevenson uncovers Ms. Magazine’s role in recovering women’s history and centering women’s historians as public intellectuals in the 1970s and 80s. In the twenty-first century, Nicole Eaton explores Hillary Clinton’s “Tribute Politics” such as her invocation of suffragists through white pantsuits in 2016, while Monica L. Mercado offers an excellent essay on the politics of suffrage centennial memorials. She concludes by imagining how marking women’s history on the landscape might move beyond monumental statues.

Other essays explore the gendered rhetoric around women in politics. Dean J. Kotlowski explores the career of civil servant Mary Elizabeth Switzer, especially at the Federal Security Agency (1939-1945). He argues that while she was mentored by the women of the “New Deal Network,” she herself “accommodated, rather than contested, the gendered strictures of leadership” in the Roosevelt administration (129). Katherine Parkin analyzes early Congressional campaigns in which widows were successfully elected on the claim that they represented their former husbands, however this undercut the idea of female politicians as individuals. Similarly, Melissa Estes Blair asserts that campaign practices of the midcentury women’s division of the Democratic and Republican National Committees reinforced the idea that women voters were white housewives, despite being staffed by career women. A growing number of married Congresswomen in the 1970s and 80s raised the question of political husbands. Though the couples’ rejected the old trope of the emasculated feminist’s husband, Sarah B. Rowley suggests their arguments unintentionally reinforced notions of manhood. Looking at the 2008 election, Emily Suzanne Johnson contrasts appeals to women voters in the campaigns of Sarah Palin and Hillary Clinton, noting the imagined voters remained white heteronormative women.

A number of the essays focus on female “firsts.” Johanna Neuman follows the 1930 campaign of Ruth Hanna McCormick, former suffragist and first woman to run for the US Senate. McCormick encountered gendered critiques–too strong and too forceful– that resonate with the judgements female candidates continue to face. Essays focused on two other firsts engage scholarship on the rise of the New Right. Kathleen Banks Nutter analyzes the “racialized white maternalism” (223) around busing in Louise Day Hicks’ campaigns for Boston’s city council to demonstrate its centrality in the rising conservative movement. Likewise, Bianca Rowlett suggests that Jeane Kirkpatrick–architect of Ronald Reagan’s Latin America policies and first permanent female ambassador to the United Nations –deserves greater recognition as a shaper of foreign policy.

In an essay on Patsy Takemoto Mink, the first woman of color elected to Congress, Judy Tzu-Chun Wu highlights the key role Mink played in envisioning and securing funding for the 1977 National Women’s Conference. Barbara Winslow follows the career of the Shirley Chisholm, the first African American woman elected to Congress. Chisholm (who makes an appearance in several essays) used her influence to help other women and people of color, from hiring an all-female staff to helping found the Congressional Black Caucus.

Indeed, the essays on women of color’s politics emphasize their unique political traditions. In her provocative essay, Wu urges us to see how Mink’s “Pacific Feminism” valued grassroots activism and the inclusion of women on the peripheries. She suggests that it offers the antecedents of third world women of color feminism, demonstrating that tradition has its own historical roots and was not merely a response to the whiteness of second wave feminism. Likewise, Holly Miowak Guise’s analysis of Indigenous activist Elizabeth Peratrovich founder of the Alaska Native Sisterhood in the 1940s points to the multiple genealogies of feminism as Peratrovich used maternalism to protect Indigenous sovereignty and bring resources to her community. Marisela R. Chávez’s review essay of Chicana activism also reveals a rich history while advocating for further scholarship.

Finally, several essays focus on women’s grass roots activism, such as Nancy Beck Young’s study of the Women’s Committee for Educational Freedom in 1940s Texas. Ellen G. Rafshoon explores how Georgia women responded to Donald Trump’s election by organizing Pave It Blue and electing many women– including Muslim, Brazilian-born, and Latina women–to the state legislature. They reflect Georgia’s changing demographics and remind scholars that we need histories that incorporate their stories. Eileen Boris concludes the collection with an expansive call to reimagine politics beyond the shadow of the New Deal’s ideal of the white male-headed household in an industrial economy by turning to the grassroots movements that defined this new generation’s emerging agenda led by women (especially women of color) around civil rights, labor, anti-sexual violence, and the environment. It is an excellent bookend to the collection’s introduction.

I have little criticism for this ambitious collection. Like Boris’s, the essays themselves often gesture toward topics that deserve further exploration. For example, Kotlowski briefly notes Switzer’s work as a disability advocate and her intimate relationship with Isabella Stevenson Diamond. But most of the women in these essays were in heteronormative relationships. Further analysis of sexuality’s impact on women in politics is worthwhile. The coded language around softball in Justice Elena Kagan’s Supreme Court nomination hearings springs to mind. And in light of the recent passing of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg we need more work on women in the judiciary. But edited collections cannot do everything. This one did a very good job and points the way forward to the next century of women’s activism.

She is the author of

She is the author of