When I was in graduate school at the University of Maryland, I worked as an intern with the Federal Judicial History Office at the Federal Judicial Center in Washington, D.C. Then, after completing my Ph.D. in 2008, I held a one-year position as an assistant historian in that office. The projects I worked on broadened my understanding of legal and constitutional history. In 2009, I helped revise the Center’s A Guide to the Preservation of Federal Judges’ Papers.[1] I also wrote Guide to Research in Federal Judicial History.[2] For this latter project, I spent days examining obscure files at the National Archives in Washington, College Park, and Philadelphia, to learn what various types of federal records could tell us about the federal courts. (The Guide to Research is available for free download here.)

Poring through these records proved an invaluable experience. I became familiar with a number of record groups at the National Archives that I otherwise never would have encountered. When I wrote my book on the famous civil liberties case Ex parte Merryman (1861), I was able to use previously untapped or underutilized manuscript sources to reframe the significance of that case. The Merryman case is famous today because of the epic clash it caused between Chief Justice Roger B. Taney and President Abraham Lincoln regarding the arrest of a Maryland farmer named John Merryman, who had burned bridges around Baltimore to prevent Union soldiers from reaching Washington, D.C.

Among my discoveries were transcripts of federal grand jury testimony describing the Baltimore Riot;[3] a letter written by John Merryman explaining why he had burned the railroad bridges around Baltimore in April 1861; private correspondence that explained why Merryman, among all of the people who could have been arrested, was the person detained by the military; and Chief Justice Taney’s manuscript draft of his opinion in the Merryman case. Using this last piece of evidence, I argued that Taney heard Merryman as a circuit justice but then did careful editing of his opinion to make it appear like he was making his decision in his capacity as Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. Even more striking, Merryman’s letter helped me unearth an extensive network of litigation that came out of the Merryman case that had previously been unknown. “The broader context of the Merryman case has been so poorly understood for a century and a half, in large measure, because historians and political scientists who have written about Ex parte Merryman have done so without consulting the original manuscript court records,” I wrote in the Introduction to Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War: The Trials of John Merryman. “Legal histories of the Civil War era typically rely too heavily on published court reports. If this book has a subsidiary point to make, it is to remind legal scholars to delve more deeply into unpublished case materials and to rely on more than the published court reports, even those reports that contain substantial supplementary documentation, as Ex parte Merryman does.”[4]

I have long believed that assigning the private writings of judges can help students better understand cases and can lead to more enriching classroom discussion. When I teach Ex parte Milligan (1866)—the landmark case in which the Supreme Court held that U.S. citizens cannot be tried in military courts when the civil courts are open and functioning—I also assign private writings by several of the judges involved with the case.[5] During the Civil War, Associate Justice David Davis—a longtime friend of Abraham Lincoln’s—had been very critical of Lincoln’s civil liberties policies, particularly the president’s use of military tribunals to try civilians for crimes that should have been tried in the federal civil courts. Yet Davis bit his tongue while the nation was at war. He sent private correspondence to Lincoln articulating his views, but he never said anything publicly.[6] I also assign the private diaries of U.S. district judge David McDonald to show how Davis and McDonald worked behind the scenes to get Milligan before the Supreme Court.[7] With these primary sources providing background, we then turn to the opinions in the Milligan case itself. In that case, Davis declared:

During the late wicked Rebellion, the temper of the times did not allow that calmness in deliberation and discussion so necessary to a correct conclusion of a purely judicial question. Then, considerations of safety were mingled with the exercise of power, and feelings and interests prevailed which are happily terminated. Now that the public safety is assured, this question, as well as all others, can be discussed and decided without passion or the admixture of any element not required to form a legal judgment. We approach the investigation of this case fully sensible of the magnitude of the inquiry and the necessity of full and cautious deliberation.[8]

I’ve found that our discussions of passages like this one are much more meaningful after my students have seen Davis’s behind the scenes machinations and private writings. Moreover, discussing how Taney and Davis approached their roles as judges in Merryman and Milligan, respectively, sets up wonderful discussions later in the semester when we get to cases like Ex parte Quirin (1942), Hirabayashi (1942), and Korematsu (1944).

In my research, I’ve continued to look for private collections of writings by federal judges that enable me to explore with my students issues related to partisanship from the bench. Recently I compiled a wonderful little collection entitled “The Politics of Judging: The Civil War Letters of William D. Shipman,” which appeared in the Spring 2020 issue of the Connecticut History Review.[9] My hope is that these letters will be of use to professors who want to discuss issues related to judicial behavior and decision making in American history.

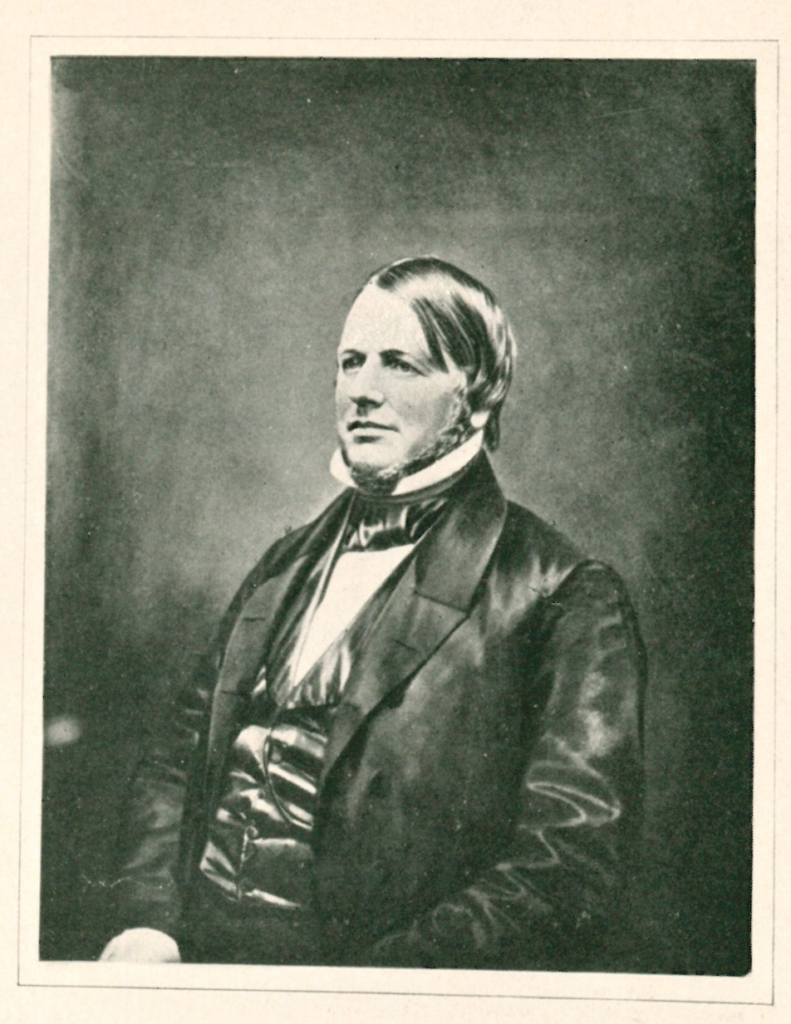

William D. Shipman was a northern Democrat with highly racist and partisan views. And yet he developed a strong reputation as an impartial judge. He served as the federal prosecutor in Connecticut from 1853 to 1860 (first appointed by Franklin Pierce, then reappointed by James Buchanan). By all accounts, he comported himself without any partisan bias or malice. As a prosecutor, he was known for his efforts to destroy the illegal trans-Atlantic slave trade.[10] The Hartford Daily Courant, a Republican newspaper, opined in 1858, “We don’t know of any Democrat who is better qualified for the position than Mr. Shipman.”[11]

In 1860, President Buchanan appointed Shipman as the U.S. district judge for the District of Connecticut. The caseload was often light in Connecticut, however, so it was common for him to preside over trials in the much busier Southern District of New York. As a federal judge, Shipman strove to be impartial and fair-minded. And, despite his racial beliefs, he appears to have treated African American litigants fairly in court. In the summer of 1861, he condemned the Augusta, a whaler suspected of being outfitted on Long Island for the slave trade.[12] His opinion gained attention throughout the nation, with the New York Evening Post praising it for doing “much toward exterminating this traffic at this port and its vicinity.”[13] Shipman’s decision in the Augusta case was significant, because for decades the federal judges in New York had been interpreting the anti-slave-trade laws so narrowly (and with such contorted logic) that the city had become, according to one historian, “a haven for the outfitting of slavers.”[14]

Later that year, in October, he presided over the case of William Tillman, a free black sailor who had been kidnapped by Confederate privateers who hoped to take him to Charleston where they could sell him into slavery for $1500. In the middle of the night, Tillman mutinied and killed his would-be enslavers. Upon reaching New York, he became a local celebrity. People lined the streets hoping to meet him. In court, Shipman awarded Tillman a significant monetary award as part of the salvage for bringing the Confederates’ vessel to port.[15]

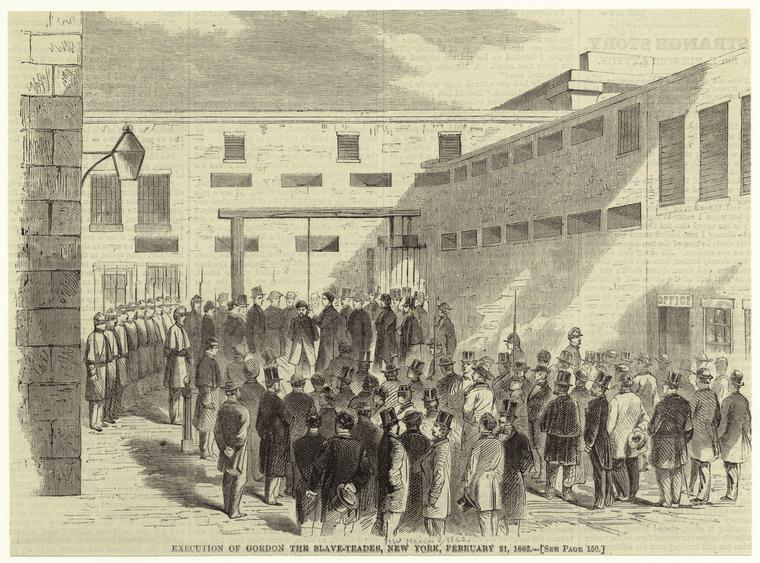

In 1861 and 1862, Shipman also presided over the two trials of Nathaniel Gordon, perhaps the most notorious slave trader in American history. Gordon had been captured off the coast of Africa in August 1860 with nearly 900 African men, women, and children crammed belowdecks on his vessel, the Erie. Gordon’s first trial, in June 1861, ended in a hung jury. His attorneys moved to have the case dismissed, but Shipman refused. The second trial, which commenced in November, ended in a conviction. At the sentencing on November 30, 1861, Shipman delivered a long, heartfelt address to the courtroom. “You are soon to be confronted with the terrible consequences of your crime, and it is proper that I should call to your mind the duty of preparing for that event which will soon terminate your mortal existence and usher you into the presence of the Supreme Judge,” he told the defendant. Shipman then implored Gordon “to seek religious guidance . . . and let your repentance be as humble and thorough as your crime was great. Do not attempt to hide its enormity from yourself; think of the cruelty and wickedness of seizing nearly a thousand fellow-beings, who never did you harm, and thrusting them beneath the decks of a small ship, beneath a burning tropical sun, to die of disease or suffocation, or be transported to distant lands, and be consigned, they and their posterity, to a fate far more cruel than death.”[16]

Shipman further implored Gordon to “think of the sufferings of the unhappy beings” who, in “helpless agony and terror” had been taken from their homeland. “Remember that you showed mercy to none, carrying off as you did not only those of your own sex, but women and helpless children.” He continued with surprisingly egalitarian language for a nineteenth-century Democrat:

Do not flatter yourself that, because they belonged to a different race from yourself, that your guilt is therefore lessened—rather fear that it is increased. In the just and generous heart the humble and the weak inspire compassion and call for pity and forbearance, and as you are soon to pass into the presence of that God of the black man as well as the white man, who is no respecter of persons, do not indulge for a moment the thought that He hears with indifference the cry of the humblest of his children. Do not imagine that, because others shared in the guilt of this enterprise, yours is thereby diminished, but remember the awful admonition of your Bible, “Though hand join in hand the wicked shall not go unpunished.” Turn your thoughts toward Him who alone can pardon—who is not deaf to the supplications of those who seek His mercy.

Shipman then declared that Gordon would be hanged by the neck on February 7, 1862. Gordon stood perfectly still, gazing straight forward as Shipman read his statement. The only time he flinched was when he heard the words, “hanged by the neck until you are dead.”

Many northerners urged Lincoln to commute Gordon’s sentence to life in prison, but the president refused. On February 4, he issued granted Gordon a two-week stay so that he might make “the necessary preparation for the awful change which awaits him.” The condemned man tried to commit suicide the night before the hangman was set to do his work. Between 3 and 4 a.m. the night before his scheduled execution, his guards “heard a moaning sound” coming from his cell. When they arrived they found him “laboring with convulsions” and “in great agony and suffering intense pain.” They immediately called for the prison physicians who administered antidotes and pumped his stomach. They would not allow him to cheat the gallows. Once resuscitated, Gordon admitted to having taken strychnine, a highly toxic, colorless alkaloid often used as a pesticide, which a friend had smuggled into the prison in a cigar. According to one report, Gordon “passed the remainder of the night in physical agony, half dead and half alive, and repeatedly expressed his wish to die.” He was hanged at the Tombs in New York City on February 21, 1862.[17] Unlike other federal judges who had come before him, Judge Shipman ensured that a barbaric slave trader did not escape justice.

For all of these sorts of decisions, Shipman won the support of prominent Republicans. E. Delafield Smith—Lincoln’s appointee as the federal prosecutor in the Southern District of New York—praised him for his “unsparing thoroughness, justice and intelligence in the discharge of the duty.”[18] Another admirer observed that Shipman “scrupulously avoided politics” as a judge and that “none of his judicial decisions were colored by partisanship.” Shipman himself was proud of his deportment as a federal judge. After the war, he wrote that he “was confronted with a series of new questions for which there was no precedent. All sorts of wild notions were addressed to me by men who were neither fitted by nature or education to deal with such matters.” Shipman had to weigh the arguments carefully in his cases. “No one will know what I went through during the war,” he wrote. “By some Democrats I was regarded in full sympathy with the administration and its party henchmen. By some Republicans I was considered a secessionist and anxious for the success of the confederacy.”[19]

Taken together, the evidence suggests that Shipman did everything he could to be an impartial judge. Yet his private correspondence reveals a very different side of his persona. When corresponding with members of the Lincoln Administration, he professed to act only with “delicacy & propriety”—what today might be called a proper judicial temperament.[20] However, in private letters to fellow Democrats, he was highly critical of President Lincoln and expressed disgust at Lincoln’s handling of the war effort.

Over the course of several years I uncovered several dozen letters written by Shipman during the Civil War Era. Most of this correspondence is held in the Samuel L. M. Barlow Papers at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California. Several letters are in various collections at the Library of Congress. Working with a student of mine, Daniel Glenn (who is in his second year at William & Mary Law School), we selected several letters for publication. The letters we chose dealt with two important moments toward the close of the Civil War: the presidential election of 1864 and the aftermath of the Lincoln assassination in 1865. Shipman’s letters will give students a great deal to talk about in classes on the Civil War and Reconstruction, or legal and constitutional history.

During the presidential election campaign Shipman was willing to wade into partisan politics, provided he did so without the public knowing. In a private letter to General George B. McClellan, the Democratic candidate for president, he revealed that he had been writing anonymous newspaper editorials in favor of the Democratic Party. “My judicial position of course forbids my mingling openly in political contests,” he wrote, but in such a dire situation as this, when the “future welfare of the people, including my own children, are at stake, I cannot remain an idle spectator.” He then proceeded to tell McClellan that he had written “a series of articles” in support of McClellan’s candidacy. “Of course I am not known as the author of anything which I write, but I have occasion to know that some of the articles have produced an impression upon your opponents.” He concluded, “I am deeply anxious for the country; and if it were not for considerations of duty which appeal to my conscience, I would resign my seat on the bench, and devote myself from now till the 8th of Nov. in urging my fellow citizens to perform their highest duty in this hour of peril.”

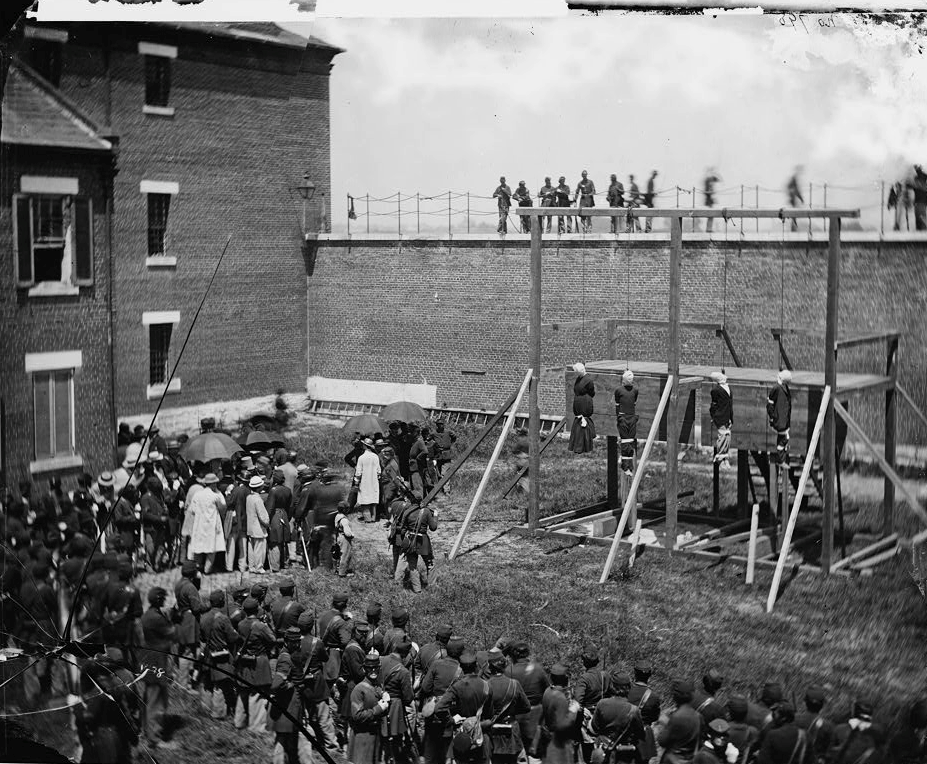

Following the Lincoln assassination in April 1865, eight conspirators were rounded up and tried before a military tribunal. Four were sent to the gallows, including Mary Surratt, the first woman to be executed by the federal government. Shipman was horrified by this swift military judgment of civilians. “I think the summary execution of the conspirators struck a deep chord in the public bosom,” he wrote to Barlow. “There were few words uttered, but the shock was almost universal, as it became known that the condemned were to die upon twenty four hours notice.”

Shipman feared that using the military to try civilians would undermine the systems of separation of powers and checks and balances that were established in the U.S. Constitution. “If some means are not taken by the American people to disavow in the most significant manner this pure assumption of power in one of its worst phases, not many years will elapse before a man’s purely political action and opinions will subject him to death,” wrote Shipman. “Pretexts will not be wanting upon which to accuse those whose opposition to a given party in power may be deemed inconvenient; and an accusation once made, everything else, to the block or halter, follows of course. The executive department of the government is thus in possession of absolute power over the lives of the citizens. I say absolute, because the President may not only define the crime and fix the penalty (the work of the legislature properly) but he may, by his temporary agents selected for that purpose, hear and decide the case.” And officers of the Executive Branch, of course, would also carry out the sentences. “Thus the whole power over life and liberty is committed to the unchecked and arbitrary will of a single man, and those rights which it was sought to guard the most carefully in the constitution, are found to be without any protection whatever. It will be a very strange event in history, if, with all the knowledge of the principles of free government that pervades the minds of intelligent men in this country, such a monstrous assumption of power can be finally sanctioned.”

Shipman’s letters also touch on other important issues of the Civil War Era, including Reconstruction politics and black suffrage. The matters they raise should capture the attention of students and also remind scholars of the importance of unearthing judges’ private writings when examining judges’ work on the bench.

[1] A Guide to the Preservation of Federal Judges’ Papers, 2nd ed. (Washington, D.C.: Federal Judicial Center, 2009). This book is now in its third edition (2018) and is available for free download here.

[2] Jonathan W. White, Guide to Research in Federal Judicial History (Washington, D.C.: Federal Judicial Center, 2010).

[3] One of the sets of grand jury testimony is now available here: Jonathan W. White, ed., “Forty-Seven Eyewitness Accounts of the Pratt Street Riot and Its Aftermath,” Maryland Historical Magazine 106 (Spring 2011), 70-93.

[4] Jonathan W. White, Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War: The Trials of John Merryman (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2011), 8.

[5] For more on Milligan, see Stewart L. Winger and Jonathan W. White, eds., Ex parte Milligan Reconsidered: Race and Civil Liberties from the Lincoln Administration to the War on Terror (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2020).

[6] Davis’s private correspondence with Lincoln is available in Peter J. Barry, “‘I’ll Keep Them in Prison Awhile . . .’: Abraham Lincoln and David Davis on Civil Liberties in Wartime,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 28 (Winter 2007): 20-29

[7] Donald O. Dewey, ed., “Hoosier Justice: The Journal of David McDonald, 1864–1868,” Indiana Magazine of History 62 (September 1966): 175-232.

[8] Ex pare Milligan (1866) 71 U.S. 109.

[9] Jonathan W. White and Daniel Glenn, eds., “The Politics of Judging: The Civil War Letters of William D. Shipman,” Connecticut History Review 59 (Spring 2020): 80-100

[10] Warren S. Howard, American Slavers and the Federal Law (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1963), 99, 155-69, 188-89.

[11] Hartford Daily Courant, March 24, 1858.

[12] U.S. v. Augusta (1861), 24 Fed. Cas. 892.

[13] New York Evening Post, September 20, 1861.

[14] Howard, American Slavers and the Federal Law, 99. See also John Harris, The Last Slave Ships: New York and the End of the Middle Passage (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2020).

[15] Jonathan W. White, “Freedom by Hatchet,” Civil War Times 57 (August 2018): 50-57.

[16] Ron Soodalter, Hanging Captain Gordon: The Life and Trial of an American Slave Trader (New York: Atria, 2006), 53-67, 107-34, 144-46; John R. Spears, The American Slave-Trade: An Account of Its Origin, Growth and Suppression (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1900), 220.

[17] Soodalter, Hanging Captain Gordon, 146-47; Lincoln, “Stay of Execution for Nathaniel Gordon,” February 4, 1862, in Roy P. Basler, et al., eds., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 9 vols. (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 5:128-29.

[18] E. Delafield Smith to Caleb Blood Smith, December 6, 1861, “Correspondence, Testimony, and Exhibits, Relating to the Slave Bark Augusta, 1861-1862,” National Archives microfilm publication M160 (Records Of The Office Of The Secretary Of The Interior Relating To The Suppression Of The African Slave Trade And Negro Colonization, 1854-72), reel 5.

[19] Proceedings, December 9, 1929, Being on the Occasion of the Presentation to the United States District Court for the District of Connecticut of a Portrait of William Davis Shipman, a Judge of Said Court 1860 to 1873 (n.p., n.d.), 15-16.

[20] Shipman to Gideon Welles, March 5, 1861, Gideon Welles Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.