Every year, the American Society for Legal History awards the Kathryn T. Preyer Scholars Prize to one or more scholars “at the beginning of their careers” to acknowledge significant, original research “on any topic in legal, institutional and/or constitutional history.” The prize includes an honorarium to reimburse costs of attending the annual ASLH annual meeting. One of the winners of the Kathryn T. Preyer Prize for 2020 is Ivón Padilla-Rodríguez. The Docket is pleased to have had the opportunity to learn a bit more about her work!

The Docket [TD]: First of all, congratulations on being named a 2019-20 Preyer Scholar! I think our readers would love to get a sense of what you were trying to accomplish with the article.

Ivón Padilla-Rodríguez [IPR]: I am honored to have been selected as a 2020 Preyer Scholar and provided the opportunity to highlight the migration, labor, and experiences of Mexican children and youth.

TD: Can you provide a few key historical moments or historical actors that you rely on to tell the story of postwar child migration and exclusion?

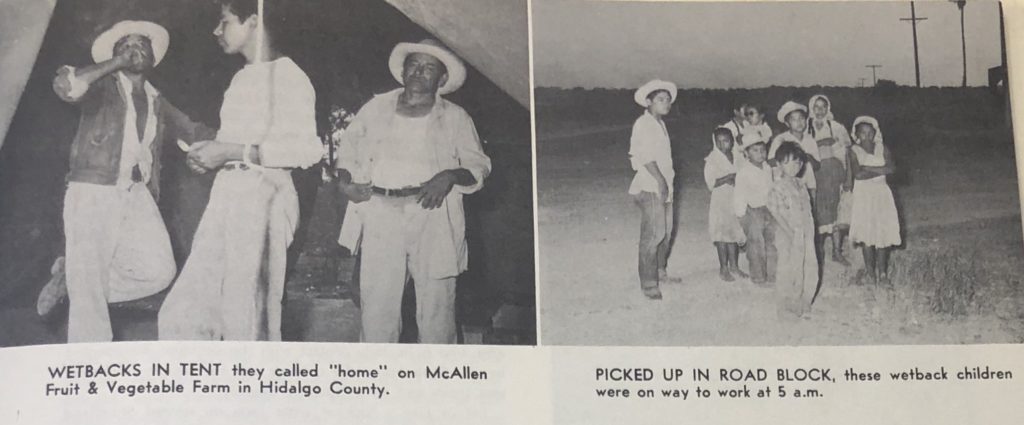

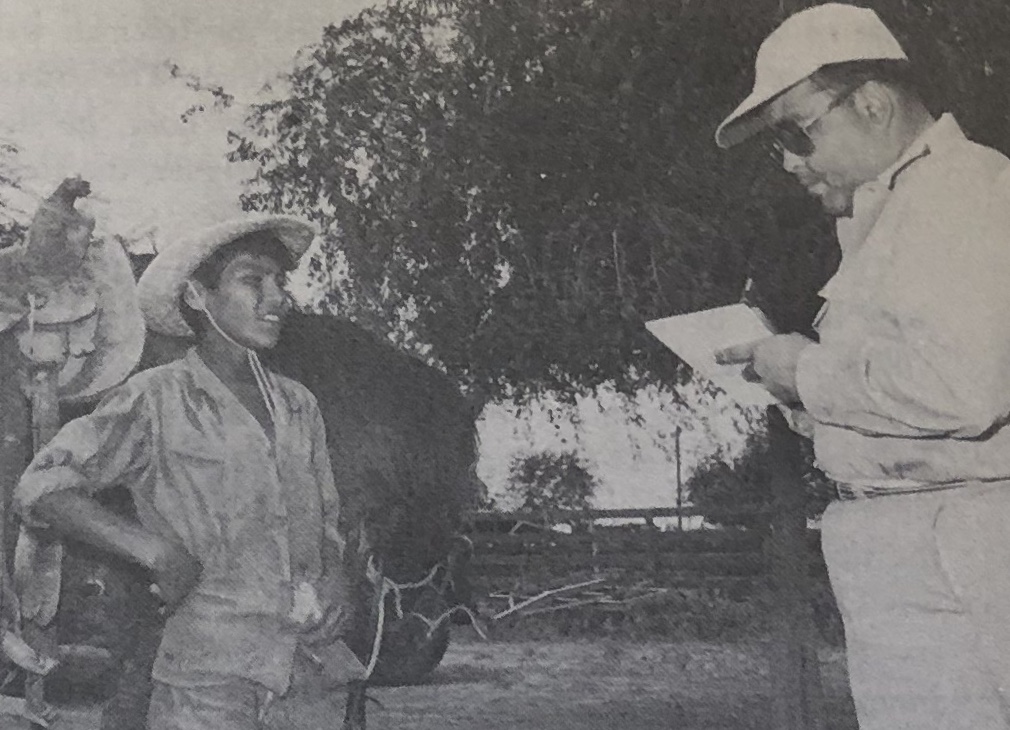

IPR: The historical actors I rely on to help tell the story of postwar child migration and the different forms of exclusion migrant youth were forced to endure are: officials at multiple levels of government service, such as Border Patrol agents, U.S. Children’s Bureau personnel, labor investigators, and welfare officials; teachers, school administrators and attendance officers; employers, employment agencies, and Mexican consuls; domestic law enforcement officials such as probation officers and juvenile court judges; child welfare and migrants’ rights advocates and researchers; and, finally, where the sources permit, migrant children themselves. Some of the key historical moments and events my research involves are situated in the years toward the end of and after World War II: the creation of the guestworker Bracero Program, the post-1940 wave of undocumented labor migration from Mexico, the “age of internal migration,” the Fair Labor Standards Act’s revision of its child labor provisions in 1949, and the mass deportation campaign of 1954 known as “Operation Wetback.”

TD: How does your paper challenge adult-centric perspectives, positioning migrant children at the fore?

IPR: The vast majority of U.S. immigration histories focus on the social and cultural experiences and the laws and policies that governed the migration of single adult males. My research challenges these adult-centric perspectives by treating migrant children and youth as central subjects of analysis and focusing on the institutional actors, laws and policies migrant youth encountered when they crossed state and international borders. Whenever possible, I try to highlight the voices and lived experiences of migrant children themselves to bring their motivations and agency to the fore. This is, of course, a persistent methodological challenge faced by historians of childhood, since children rarely leave behind their own written records, much less the most marginalized and transient among them.

TD: In what ways does your research explore the intersection between child migrants and the law in postwar America?

IPR: My paper uncovers an overlapping set of legal regimes composed of federal child labor regulations, state residence requirements, compulsory school attendance and border enforcement policies that jeopardized the welfare of all border-crossing Mexican youth, making even U.S.-born children of immigrants subject to a domestic form of migrant exclusion. My research shows that, at mid-century, the legal citizenship of the U.S.-born youth became so denuded that their migration across state borders was not unlike the experiences of their undocumented counterparts. The legal mechanisms of the domestic apparatus of (im)migrant exclusion, paired with the broad racialization of the criminal and invading “wetback” of all ages, enabled the educational deprivation, labor exploitation, and criminalization of nonwhite and mixed-status migrant youth at the border and interior of the nation.

TD: Could you tell us about your research background? What was it like doing the archival research for this piece? Do any memories from the archives stand out to you?

IPR: My undergraduate and graduate-level research has been motivated by my desire to identify and address the child-centered consequences of long-established border enforcement practices, discriminatory legal regimes, and citizenship restrictions to the welfare state. To this end, I presented research on the impact of immigration reform on mixed-status, Latinx families to members of the United States Congress in 2014; co-edited an anthology about the lives and experiences of undocumented young people in 2015; conducted undergraduate research and oral histories on late-twentieth century Central American child migration; and worked as a research assistant for non-profits in the U.S. and Mexico, conducting historically-informed policy research on child and family migration throughout my PhD program. I am now at work on a sociolegal history of child migrants in the twentieth century. Doing archival research for this essay required sifting through a vast array of documents, located in geographically disparate and overlooked archival collections. Some of these neglected sources include commissioned studies about “unattached” and “transient” border-crossing Mexican children, Border Patrol correspondence about “wet farm families,” recently screened family labor contracts in Texas, and early and mid-twentieth century residence statutes and school attendance laws. A memory that really stands out to me from the archive was discovering one of only two letters I would find during my archive trips written directly by migrant children. This letter was extraordinary because a migrant Mexican teenage girl wrote to President FDR to inquire about the nation’s child labor laws and advocate for her family’s economic and physical well being.

TD: We understand that you have done research for the federal government on child and family migration–that is incredible! Can you tell us more about that experience?

IPR: In 2016, I worked for the Office of Policy & Strategy at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), the legal immigration and benefits-granting agency of the federal government. I conducted research on Special Immigrant Juvenile Status (SIJS)—the only child-centered humanitarian visa in existence for undocumented minors—and mass migration to the U.S. I authored two different policy reports while at USCIS. One of those reports recounted the legislative and legal histories of SIJS and its application over the years, and the other depended on historical insights to create a predictive model with which to identify and address future waves of mass migration. My work at USCIS allowed me to see firsthand the versatility and applicability of historical expertise and knowledge in non-academic environments with policy implications.

TD: Do you see yourself as a scholar activist?

IPR: Yes, I absolutely see myself as a scholar activist. I am deeply committed to equitable higher education access, the advancement of immigrants’ and children’s rights, decarceration, and the abolition of white supremacy. I believe that academic scholarship—and historical research that centers the voices, experiences, and legal rights of marginalized populations, in particular—can inform and move legal, legislative, and social advocacy on these important topics. I use my own scholarship and the analytic tools I have gained from conducting research on the legal history of child migration to support the work of practitioners and intervene in public debates about child migration.