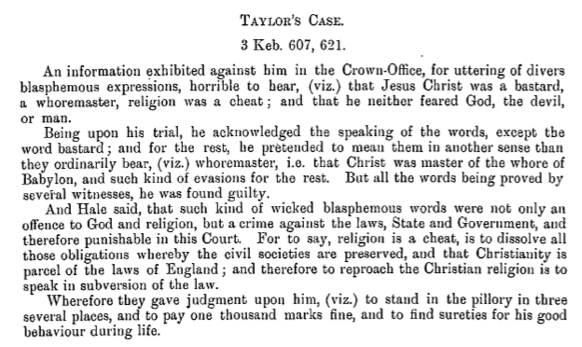

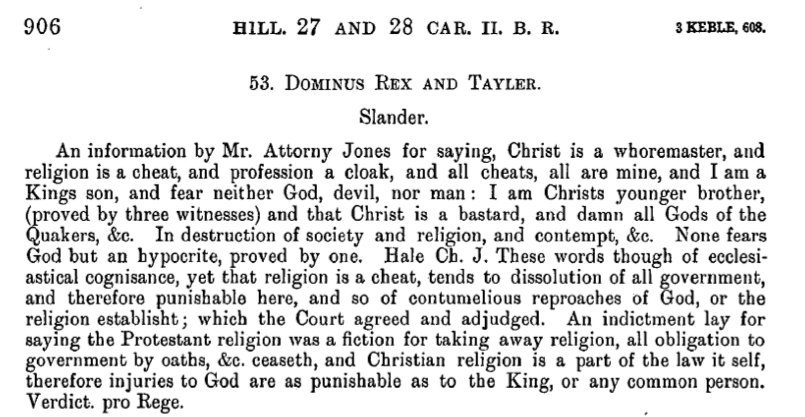

‘Christianity is parcel of the laws of England,’ declared Matthew Hale, Chief Justice of the Court of King’s Bench. Hale made this claim when sentencing John Taylor, brave or foolish enough to call religion a ‘cheat,’ and Christ a ‘whoremaster’ and ‘bastard’ in 1675. Hale fined Taylor ₤1,000, sent him to the pillory, and ordered his imprisonment. In the years since he delivered it, Hale’s dictum has had a long life. Within the law, it was cited in blasphemy trials in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries, regarding Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason and Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, and in House of Lords debate in 2005. Outside the law, it was excoriated by John Stuart Mill as a restriction on ‘freedom of discussion.’ More recently, scholars have cited it as evidence that seventeenth century England was a confessional state in which ‘Church and State’ were unified.

Though Hale’s dictum has survived into the twenty-first century, the circumstances which gave rise to it are less well remembered, and once brought to view they modify its meaning and the way in which we view seventeenth century England. When convicted in King’s Bench, the highest common law court in the realm, Taylor was a farmer. But he had been a preacher during the Interregnum, the period between the execution of Charles I in 1649, and coronation of Charles II in 1660, during which conformity with the Church of England was not enforced. Taylor’s preaching was particularly heterodox: according to A Full and True Account of the Notorious Wicked Life of that Grand Impostor John Taylor, his articles of faith included promotion of sect members’ ‘Carnal knowledg of each others Wives.’[1] By 1675, conformity with the Church of England was required by a brace of statutes known as the Clarendon Code. Charles II had sought to mitigate these laws in 1672 through a Royal Declaration of Indulgence, a move made possible by French financial support, agreed upon in the secret Treaty of Dover. Though it was withdrawn in 1673 following protests by parliament that the king could not make law regarding religion without its support, Charles’s Declaration may have inspired Taylor’s outburst. In short, Taylor’s life traversed the religious and governmental upheaval of seventeenth century England.

Perhaps more significant, Taylor’s Case reveals two contests at play in Hale’s judgment relating to the exercise of sovereignty and the relationship between Church and state in early modern England. The pervasive image among scholars of the English Restoration is that of a Church and state union, a position championed, in particular, by J. C. D. Clark in his 1985 work English Society, 1688-1832, reprinted in 2000 as English Society, 1660-1832. There is superficial evidence to support Clark’s argument. The Clarendon Code statutes required taking the oath of allegiance and the Sacrament in accordance with Church of England practice to hold civil office, prevented meetings of nonconformists, prevented nonconforming preachers from returning to their parishes, and established ecclesiastical uniformity.

The problem with this argument is that legislation was only part of the story of the regulation of religious conformity; how it was applied, and whether it was applied, remains unaddressed. And this is one of the reasons why Taylor’s Case is so important, for it provides an opportunity to test the reception of legislation in court. Indeed, though Clark cites Taylor’s Case as evidence for the enforcement of the Clarendon Code statutes, and thus evidence of confessionalisation in legislation and courtroom, Hale eschewed the language of statute in his judgment. Offences like Taylor’s had long been governed as the religious offence of heresy, an offence triable in ecclesiastical courts, which were administered directly by the Church of England, unlike the common law courts. The key framing of statutory heresy was of heresy as an offence ‘spiritual’, for endangering the Church and its salvific role, and ‘temporal’, for endangering the peace of the realm. By the seventeenth century, Church courts had abandoned this framing, treating heresy as an exclusively spiritual offence. But the language of spiritual and temporal danger remained in statute, underpinning the Act of Uniformity, one of the Clarendon Code statutes.

In contrast to legislation and Church court practice, Hale rested his judgment on exclusively temporal foundations. He did this by describing Taylor’s offence not as heresy or nonconformity, but as defamation. Defamation was a longstanding common law offence, which had developed within the common law itself through the accumulation of judicial precedent over time, rather than through the legislative involvement of king and parliament. It was defined as the uttering of insulting words that caused or threatened temporal damage, and was a civil and criminal action; those accused of defamation could be sued in court for damages by the slandered party, or criminally tried for breaches of peace. Taylor’s offence was hardly a conventional example of defamation, and Hale relied on extensive linguistic improvisation to frame it in line with precedent.

Hale described Taylor’s words as insults: they were ‘contumelious reproaches.’ And they threatened temporal danger, risking the dissolution of ‘civil societies’ and ‘all government.’ But the slandered party was not a man or woman, but ‘God, or the religion establisht.’ Explaining his reason for regarding God as possessed of legal personality, Hale claimed that, as Christianity was part of English law, offences against God ‘are as punishable as to the King, or any common person.’ In sum, Hale modified common law defamation to present Taylor as having uttered insults against God that threatened temporal damage. In doing so, he explicitly framed his judgment as temporally oriented.

We now come to the heart of the meaning of Hale’s famous pronouncement. While he acknowledged Taylor’s words were of ‘ecclesiastical cognisance,’ and thus able to be tried in a Church court, they were ‘punishable here’ – in common law – because they ‘tend[ed] to the dissolution of all government.’ In other words, Taylor was on trial because his words were temporally dangerous. Given this context, Hale’s contention that Christianity was part of English law was most likely an allusion to the Clarendon Code’s requirement of confessional uniformity. Certainly, his dictum was not an assertion of Church-state unity. How could it be, when he explicitly contrasted the work of the common law against that of the Church courts? Rather, in ignoring the Church’s concerns regarding salvation for the imperative of state survival, Hale subordinated spiritual authority to temporal.

Does any of this matter for the world today? It does. First, if Taylor’s Case reflected the subordination of spiritual to temporal authority, then we ought to view it as a key moment in the history of the Church’s legal diminution. Our conventional narrative of the displacement of religion in the West treats secularisation as a consequence of liberalism begetting a humane, rational epoch, of which we are the inheritors. But Taylor’s Case suggests it was not the normative doctrines of liberalism, but the temporal quest to preserve the state that saw the Church’s marginalisation. Second, the case for sovereignty understood as the total control of a territory remains a potent political claim, central to arguments in favour of Brexit. But Taylor’s Case shows that, within English law, such claims were rejected in favour of an understanding of sovereignty as legally marginal. English society has always been more complicated than the rallying cries of philosophers and politicians have acknowledged.

[1] A Full and True Account of the Notorious Wicked Life of that Grand Impostor John Taylor (London: 1678), 3.

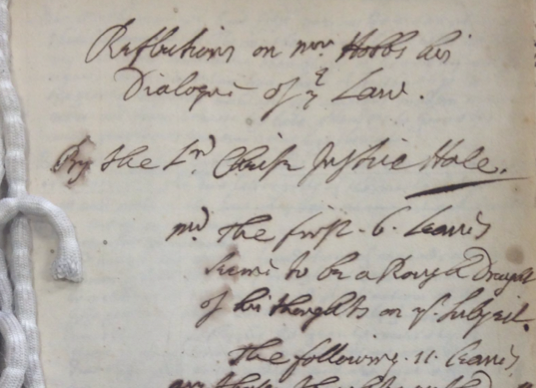

David Kearns’s article “Sovereignty and Common Law Judicial Office in Taylor’s Case (1675),” appears in Law and History Review 37.2.