The 1880s in the British colony of India saw the emergence of the “New Women,” reflected in numerous writings by women speaking against their suppression and subordination. This meant that womens issues were no longer an adjunct issue, but a core issue of women living in the “shade of Manu,” who had so far been deemed incapable of independent action and thoughts.[1] Women of this era also challenged the existing Hindu ideologies with the claim that “we need new Sastras,” so as to remove religious obstacles for equality among genders. Feminists including Tarabai Shinde critiqued, for example, the sentencing of a young child-widow of Brahmin caste who killed her illegitimate child (1881), and called it ‘Brahmanical patriarchy’, in her book, Stri-Purush tulana (A Comparison between Men and Women): “So is it true that only women’s bodies are home to all the different kinds of recklessness and vice? Or have men got just the same faults as we find in women?”[2]

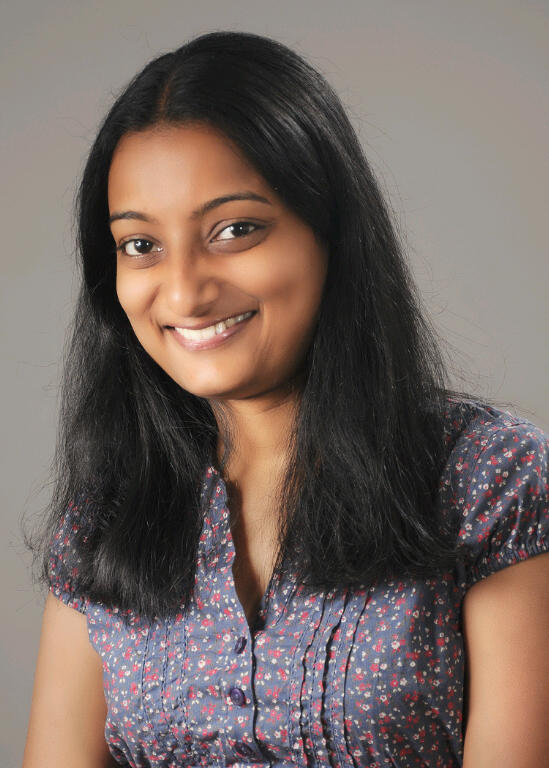

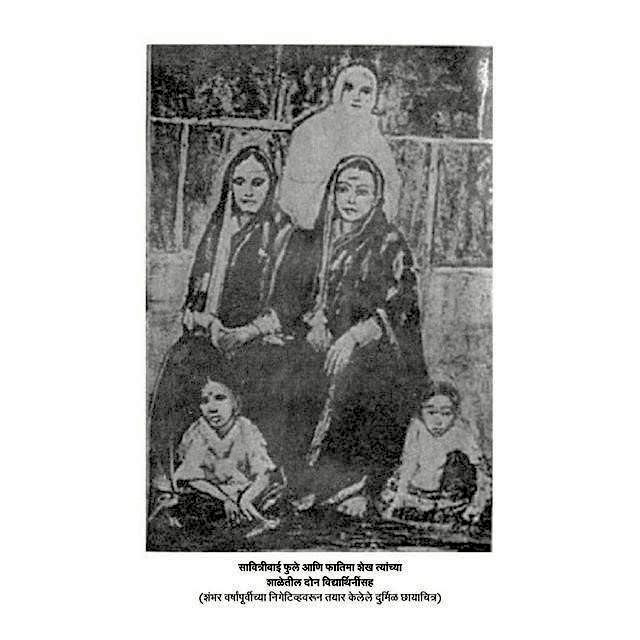

These views were endorsed by the reformers Jotiba Phule (1827–90) and his wife Savitribai Phule (1831–97). Among other endeavours, they opened the first of its kind Dalit girls’ school and taught alongside colleagues from other religions, notably Fatima Sheik, a Muslim woman teacher. This was also a period of emergence of numerous feminists who campaigned against a host of issues including child marriage and saw the formation of associations and schools run by women for the welfare of girls and women.

The emergence of the “New Women” brought about discussions to increase the age of marriage for women, and to enable an age for consummation of the marriage. The colonial government’s attempt to raise the age of marriage for Indian women was coloured with questions of nationalism and tradition. British intervention was deemed to be unacceptable on the ground that imported customs and practices would be anti-traditional and, therefore, this was anti-national.

In the public debates that emerged around this topic by Indian social reformers in the 1890s, the focus was on the need to regulate the age of cohabitation and consummation of marriage rather than on the age of marriage. The age of consummation of marriage was slated to be increased from 10 years to 12 years so that sexual abuse within the institution of marriage was curbed. In 1891 the age of consummation of marriage, irrespective of the early marriage was made to be 12 years. Later studies show that this measure “ignited political hostilities between reformists and religious orthodox figures as well as antipathy towards the colonial state.”[3]

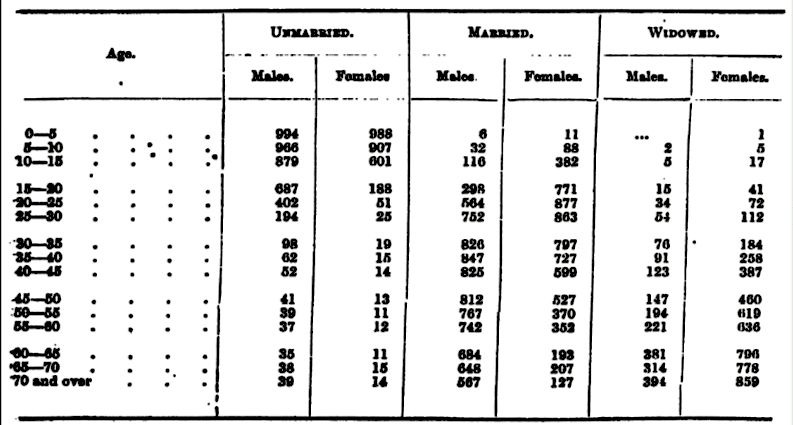

This paved the way for the practice of early marriage being countered by feminists and women who associated raising the age of marriage as a step towards building a healthy nation by reducing the child and mother mortality rate and enabling the health of new born, the health of girls, reduce violence associated with forced sex and bring down household responsibilities that are forced upon young girls at an early age that resulted in loss of education for them.[4] This was especially true for marriage of infants and children of tender age, as is seen in Table 1.

Earlier attempts on secular lines were made to increase the age to at least 14 years for girls and 18 for boys if not more under the Special Marriage Act, 1872, Brahmo Marriage Act, 1872 and the Indian Christian Marriage Act, 1982.

The raising of the age of consent for sexual relations in marriage, raising of the age of marriage in secular marriages, and a rise in public interest as a result of nationalist movements gathered momentum in the 1920s that brought to the forefront the problems of child marriage.[5] These women brought forth the needs of women by forming associations, developing institutions and critiquing rulers, both foreign and societal, thereby consolidating women’s interests and viewpoints. Critique of the movement emerged almost simultaneously with greater cohesion of the family being advocated through early marriages.

The attempt made in 1928 by Harbilas Sarda to criminalize marriage and sex with a girl below the age of 12 proved to be the most successful, and aimed to set the age of marriage at 14 for girls and 18 for boys. Thousands of conservative Hindus and Muslims protested against this bill. However, women’s organizations around this time held grassroots meetings promoting both the 1925 and 1928 Bills by correlating it to female health and access to educational opportunities for girls with the general consensus that girls below the age of 16 years should not engage in sexual relations.

An example of the rallying in support for the bill included the address by the Rani of Mandi to the AIWC in 1928 wherein she stressed on the practice of child marriage as common among Hindus and Muslims, and that ‘‘it is incumbent upon us to stop this evil’’ of child marriage. A small standing committee to report on the progress of bill in the legislature and to raise public awareness was also inaugurated with support from the Begum of Bhopal.

In 1929, a survey demonstrating the problems of child marriage was used by women’s groups to lobby for the Child Marriage Restraint Act (CMRA) and. The All-India Women’s Conference with its alliance with the Indian National Congress began the campaign for the CMRA. The CMRA saw uniting of Hindu and Muslim communities, except for opposition in small sections.[6] In the end the CMRA was passed and included Muslims but compromised on the minimum age of marriage for women at 14, and for men at 18. The age of consent was not mentioned. [7]

Significantly, child marriages post CMRA were neither

declared as void nor were they non cognizable. This resulted in the absence of

state intervention in child marriage thereby leaving the society to its own

means to regulate child marriages. The meagre fines that were to be imposed on

child marriage under the CMRA were seen as an extension of the dowry payable by

the girls’ family.

[1] See generally, Sarladevi, “A Womens’ Movement,” MR (Oct 1911) p. 345, as cited in Geraldine Forbes, The New Cambridge History of Women, Women in Modern India, Vol. 4 (CUP, 1996), p. 70.

[2] Tarabai Shinde, Stri Purush Tulana (1882) translated by Rosalind O’Hanlon. A Comaprision between Men and Women (OUP, 1994).

[3] Rajani Bhatia, Ashwini Tambe. Raising the age of marriage in 1970s India: Demographers, despots, and feminists, Women’s Studies International Forum, vol. 44 (May-June 2014), p. 90.

[4] Ibid at 89–100.

[5] Literature on these aspects is available in a host of writing that includes Mrinalini Sinha, Specters of Mother India: The Global Restructuring of an Empire (Duke University Press, 2006).

[6] WIA, Appendix, Report 1930-31, “Muslim Ladies Defend Sarda Act.”

[7] Samita Sen, Policy Research Report On Gender And Development Working Paper Series No. 9, Toward a Feminist Politics? The Indian Women’s Movement in Historical Perspective (January 2000).