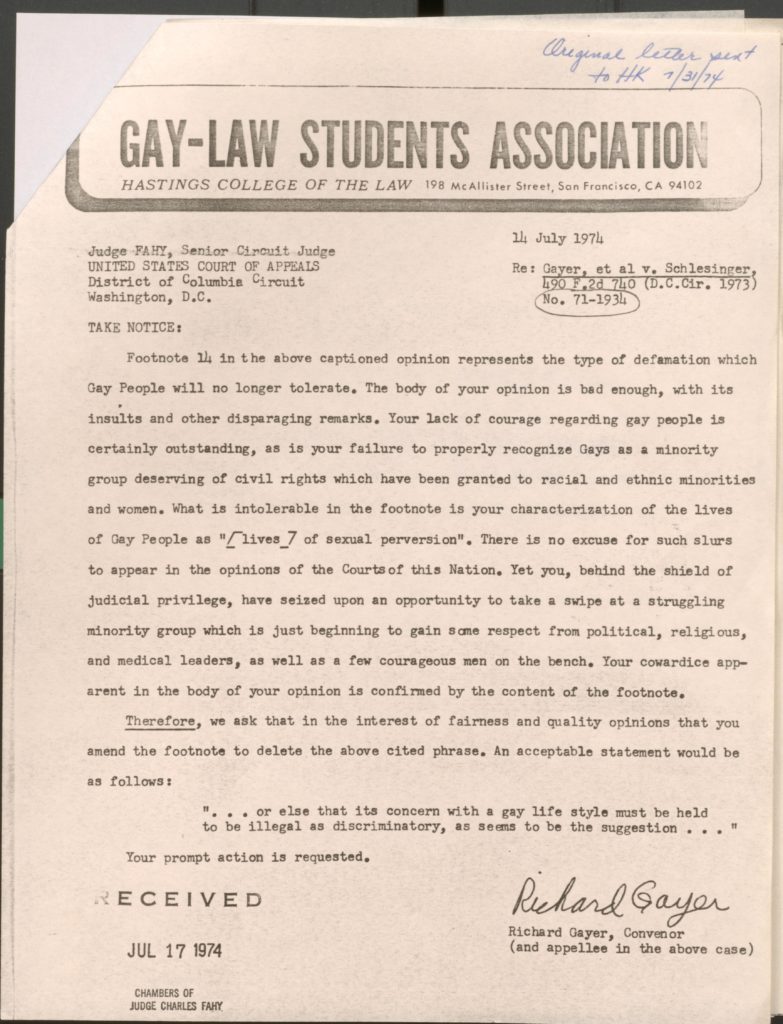

San Francisco resident and LGBT activist, Richard Gayer had had enough. A plaintiff in a suit against the government regarding the denial of his security clearance due to his homosexuality, Gayer wrote angrily to appellate judge Charles Fahy following a 1973 decision in Gayer, et al v. Schlesinger, focusing notably on footnote 14. “The body of your opinion is bad enough, with its insults and other disparaging remarks. Your lack of courage regarding gay people is certainly outstanding, as is your failure to properly recognize Gays as a minority group deserving of civil rights which have been granted to racial and ethnic minorities and women.” Gayer rejected Fahy’s characterization of the LGBT community in the footnote as conducting “[lives] of sexual perversion,” arguing that such slurs had no place in judicial opinions. “[Y]ou, behind the shield of judicial privilege, have seized upon an opportunity to take a swipe at a struggling minority group which is just beginning to gain some respect from political, religious, and medical leaders, as well as a few courageous men on the bench. Your cowardice apparent in the body of your opinion is confirmed by the content of the footnote.”[1]

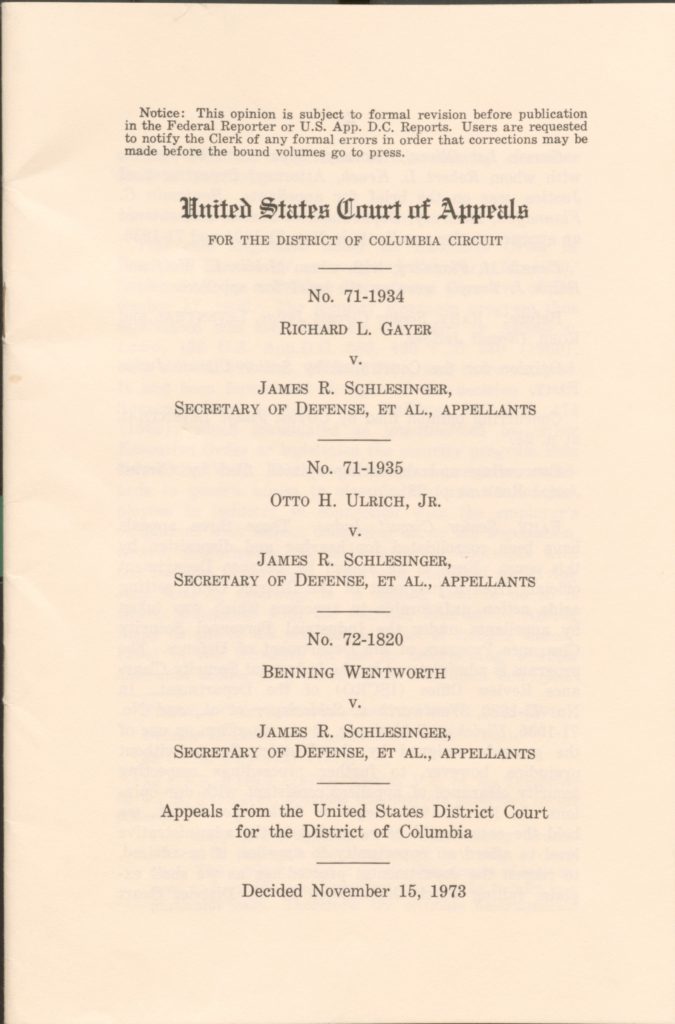

While the subject of security clearance policy might seem somewhat esoteric, during the 1970s, the process for granting clearances ran head long into the growing LGBT rights movement. The 1973 ruling included three cases, Wentworth v. Laird, Ulrich v. Laird and Gayer v. Laird (later changed to Schlesinger to reflect the then current Secretary of Defense) found in the papers of appellate judges Charles Fahy and Harold Leventhal in the Manuscript Division at the Library of Congress reveals a court grappling, or perhaps more accurately, struggling with ideas regarding sexuality that would take decades to address, but also illustrates how federal judges approach, shape, and rule on such cases. Researchers can find the division’s full array of federal judges in its recently published library guide: The Federal Paper Chase.

Earlier cases such as Scott v. Macy and Scott v. Macy II pushed back against naked exclusion of homosexuals in government and regarding clearances. Both cases endured defeat in the district Court and semi-victories at the appellate level.[2] In the second case, Judge Carl McGowan’s opinion proved somewhat ambiguous, notes historian Eric Cervini, as the judge acknowledged that public policy on the issue remained in flux and the court was asking for a “clear policy line to the demarcation of appropriate disclosure requirements.”[3]

Gayer et al. v. Schlesinger

McGowan’s ruling was soon after followed by the convergence of three other clearance cases involving Bennington Wentworth, Otto Ulrich, and Gayer. Gay rights pioneer Frank Kameny had initially represented each in board hearings with the government. Despite repeated appeals to have the hearing open to the media, the government refused. Kameny and fellow activist, Barbara Gittings who often worked with him on such appeals, recognized the importance of educating the public on issues of sexuality through newspaper and television coverage. The proverbial closet had only made gay men and lesbians more threatening not less; homosexuality served as a useful societal scapegoat and homophobia remained pervasive. The government’s first open appeals hearing would take place in 1972 Los Angeles, and perhaps in part due to the media exposure that followed, would make Otis Tabler Jr. the first openly gay individual to attain a security clearance in 1975.[4]

The specifics of each man’s ordeal differed slightly, but some general similarities can be drawn. Wentworth, Ulrich, and Gayer all openly admitted their homosexuality which then freed them from possible blackmail over the issue, one of the most cited reasons provided by the government for denying clearances. Predictably, each found their security clearance revoked and/or denied, though the reasons and tactics somewhat differed.

For Wentworth, government examiners pointed to testimony that Wentworth had engaged in sexual activities with a minor. Despite Wentworth’s disavowal of said relationship, the government used the testimony as reason to revoke his clearance. Moreover, one of the government examiners adjudicating the appeal hearing admitted he had dismissed Wentworth’s testimony regarding the alleged relationship due to his homosexuality and suggested that though theoretically possible for an active homosexual to obtain a clearance, he could not conceive of conditions under which that might become a reality.[5]

The District Court had “characterized” the questions put to Wentworth by investigators, which included very specific inquiries regarding various sexual acts, “as “shocking.” The court ruled that the interrogation amounted to an “unjustified invasion of his privacy while also serving to prejudice” the hearing as a whole thereby denying “Wentworth a fair and impartial adjudication.”[6]

The second case involved Otto Ulrich. While a technical aide for Bell Labs in New Jersey, Ulrich had become a member of Mattachine Society of Washington (MSW) founded by Kameny. He maintained his membership for several years and participated in the MSW’s 1965 picketing of the Pentagon for the Department of Defense’s discriminatory hiring policies, a protest for which the government had been pursuing him for several years even circulating a photo of Ulrich among his former co-workers at the Library of Congress.[7]

In 1968, he began a job with Bionetics Research in New Jersey and having admitted his MSW membership was denied a security clearance. During his government hearing, Ulrich bristled at the examiner’s questions such as “the nature of acts [he] engaged in, their frequency, surrounding circumstances, the number of persons and the duration of their relations.” Ulrich subsequently refused to answer and informed the screening board that he had already disclosed his sexuality to his employer and secured an exemption from the military due to his homosexuality, so his sexual orientation was widely known.[8]

Electrical engineer, Richard Gayer represented Kameny’s first West Coast case.[9] As with Ulrich, Gayer acknowledged his membership in two homophile organizations, Society for Individual Rights (SIR) and the Janus Society, and soon found his clearance revoked. Gayer’s sexuality had also long been publicly known. He served as a liaison between San Francisco’s LGBT community and the city’s police and religious leaders. While Gayer acknowledged his homosexuality, he too refused to answer what he deemed to be intrusive and unnecessary questions regarding his sexual activity.[10]

After exhausting all administrative options, Wentworth, Ulrich, and Gayer, with the help of the ACLU and NCACLU took their cases to the federal courts finding victories in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia Circuit. However, the government appealed each of the decisions resulting in their aggregation at the appellate court before a three-judge hearing consisting of Judges Harold Leventhal, Charles Fahy, and Roger Robb.

Having heard the appeal in late January 1973, by May, Fahy indicated to Leventhal that the two judges had achieved a general common ground on the issue, but anticipated a dissent from Robb.[11] Beginning later that month, Leventhal and Fahy exchanged memorandum regarding an early draft of Fahy’s decision.

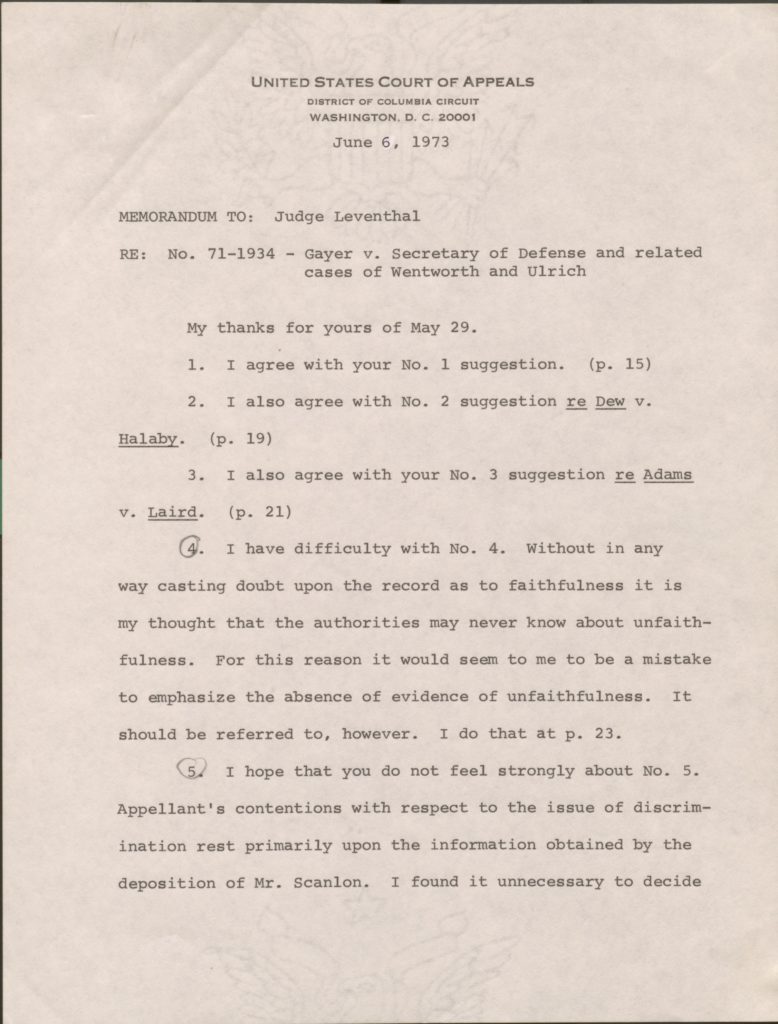

Charles Fahy to Harold Leventhal with annotations by Leventhal, June 6, 1973, Box 81, Harold Leventhal Papers p. 1.

Charles Fahy to Harold Leventhal with annotations by Leventhal, June 6, 1973, Box 81, Harold Leventhal Papers p. 2.

The exchanges between Fahy and Leventhal reveal a legal system, and larger society, struggling to address issues of sexuality. The law clerk’s summary of the cases identified several perplexing issues undermining the government’s larger policy, notably the possibility of a per se rule against gay and lesbian employees. Wentworth’s case in particular raised questions of equal protection since without a “discernible rational basis for distinguishing between homosexual acts and other illegal sexual activity” the failure to police both gay and straight employees equally despite “both types of conduct giv[ing] rise to the same susceptibility to blackmail.” Denying clearances based on an appraisal that deemed certain sexual activities “criminal” must be applied equally to applicants regardless of sexual orientation.[12]

A series of memorandum exchanged between Fahy and Leventhal from late May to late June of 1973 demonstrate the intersection between sexuality and law, but also the judges’ own struggle to come to terms with homosexuality as a political, social, and legal identity.

Fahy had shared an early draft of the opinion with Leventhal on May 23, 1973. “I have a number of suggestions with respect to the proposed opinion … But I begin by saying that I think you have handled with great skill and patience what is necessarily a sensitive and almost intractable problem,” Leventhal wrote six days later. The judge pointed out that a precedent such as Adams v. Laird, in which the plaintiff denied his homosexuality despite evidence to the contrary, was not applicable since all of the plaintiffs in the 1973 trial openly admitted their sexual orientation.[13] In regard to Wentworth’s personal trustworthiness, Leventhal asked that a statement attesting to the “absence of any record of unfaithfulness to duty,” be added to the opinion. Fahy agreed to reference this information but cautioned it did not prove loyalty, “the authorities may never know about unfaithfulness.” Leventhal argued even if inconclusive it mattered materially.[14] Leventhal pursued such “material” evidence throughout his correspondences with Fahy.

Leventhal also questioned the government’s denial of a per se rule regarding LGBT employees, writing that “[s]uch a rigid standard” suggested a possible a violation of the equal protection clause.[15]

Both Gayer and Leventhal raised the issue of equal protection. The long civil rights movement had fought hard to make the 14th Amendment’s promise of equal protection under the law a reality. The developing homophile movement believed equal protection could apply to the LGBT community as well. Dating back to the original Mattachine Society in Los Angeles, several founders of the organization including Harry Hay asserted that racial identities were also political ones; though defined by sexuality, so too was a homosexual or gay identity.

Sharpened by the events of World War II in Los Angeles – Japanese internment, the Zoot Suit Riots, and continuing prejudice against African Americans – Hay argued that these identities served as political formations around which groups could organize for rights. “To be homosexually active in Los Angeles in the 1950s, they argued, was equivalent to belonging to a racial minority group,” observers historian Daniel Hurewitz. “It conferred the same kind of identity, resulted in the same kind of oppression, and demanded the same kind of political action.” Though resisted initially, this identity eventually came to operate as undergirding to the modern LGBTQ community. It distilled perfectly “the politicization of the personal and the personalization of the political,” that shaped the nation in ensuing decades.[16]

Admittedly, the homophile movement had waned by 1974, eclipsed by the more militant Gay Liberation Front, but Gayer’s use of this argument and Leventhal’s concerns regarding it, demonstrate its slow accretion into American life and jurisprudence. Later in 1973 after the court’s ruling, the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its list of mental illnesses.

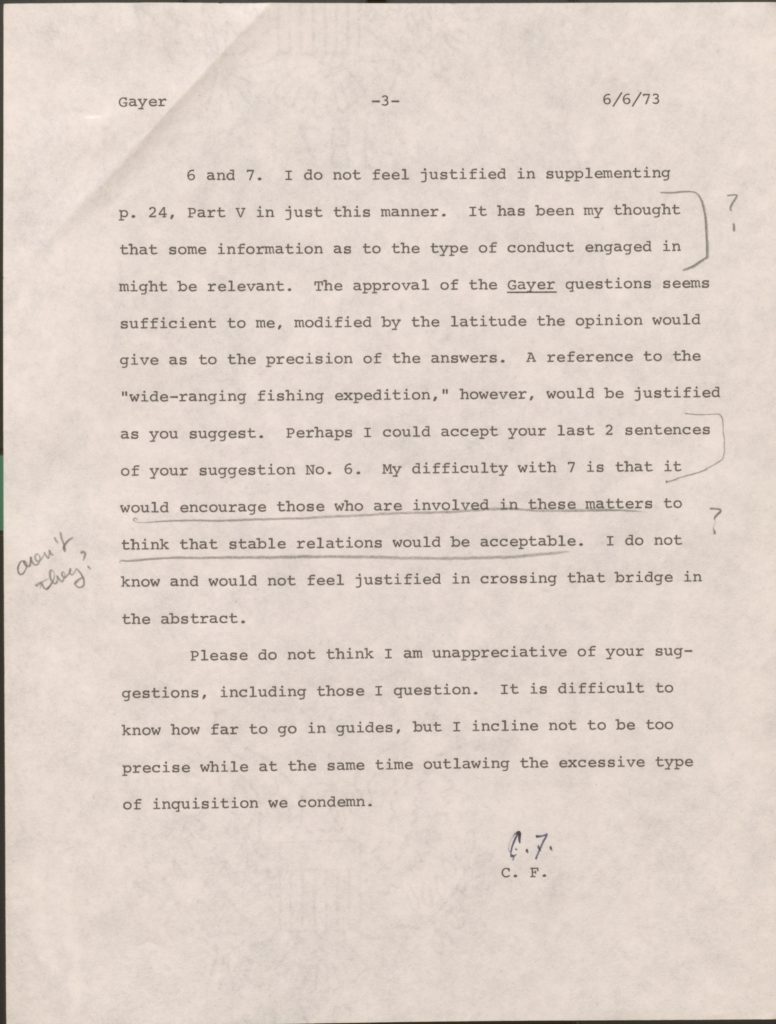

Leventhal also took issue with the nature of the questioning by officials agreeing with the District Court’s description of them as “shocking.” He requested that Fahy add language to the opinion that discouraged a process that pries into “the precise types of homosexual activity involved,” such intrusions exceeded the government’s authority. He continued characterizing the government’s questioning as “a wide-ranging fishing expedition” and that the government had failed “to develop a coherent and ascertainable approach for determining what homosexual activity and pattern is grounds for the denial of security clearance.”[17]

Fahy disagreed. Evidence of a per se rule rested on the deposition of one government examiner. The judge would not “foreclose … a rule denying security clearances to active homosexuals…” The government very well might have an acceptable rationalization and Fahy believed that “in the context of security clearances,” there might be a difference between “heterosexual activities which are criminal and homosexual activities or other forms of sexual perversion,” a point he made sure to add in the same footnote 14 that had drawn Gayer’s 1974 response.[18]

Unlike his colleagues, Robb and Fahy, Leventhal was able to both conceive of and accept LGBT relationships. He categorized as “material … established relationships that are stable and enduring,” differentiating them from “impersonal, brief relationships, accompanied by the kind of public promiscuity, as in seeking partners in public restrooms.”[19]

Again, Fahy disagreed. While willing to acknowledge that government examiners appeared to be casting their inquisitory net too wide, he held to the belief that officials had the leeway to inquire about the type of sexual conduct in which the Wentworth, Ulrich, and Gayer engaged. Fahy could not overcome his own discomfort with same sex orientation writing to Leventhal that he did not want to encourage LGBT couples to “think that stable relations would be acceptable.” A point to which Leventhal, annotated on his copy of the memorandum in the margins, “Aren’t they?”[20]

Judge Leventhal made one more attempt to shape the majority opinion. “This case is indeed vexing,” he wrote later in June. He asked Fahy to reconsider his point about Wentworth’s long record of faithfulness admitting that while not conclusive, that it still had “impressed the District Court.” If one is allowed some interpretation of Leventhal’s margin notes from his copy of Fahy’s June 6 memorandum, he seemed to indicate that stable, same sex relationships should be acceptable for security clearances and society more generally, but in his June letter to Fahy, the judge backed away from such an opinion. “I do not propose that we say all stable relationships are acceptable,” he wrote omitting any reference to sexuality, “but I certainly think this quality in the relationships is ‘material.’” Leventhal held to his argument that the government could not on the one hand, declare homosexual acts criminal while heterosexual acts of similar nature also remained criminal but remained “widely understood not to be cause for unfavorable security action.” Officials need to identify “what is the extra ingredient, over and above the fact of criminality, that justifies the way they have handled the matter?”[21]

Fahy assented to several but not all of Leventhal’s requests. He acknowledged that Wentworth’s thirteen-year record of loyalty and good service though “not conclusive,” did matter materially. He also added that the government’s questioning amounted to a “wide ranging fishing expedition,” and that the process was “indicative … of an ill-defined approach to the problem which has not been justified.” Fahy, however, remained steadfast in his opinion that some difference existed between homosexual and heterosexual acts and that in regard to a security clearance “might be justified.”

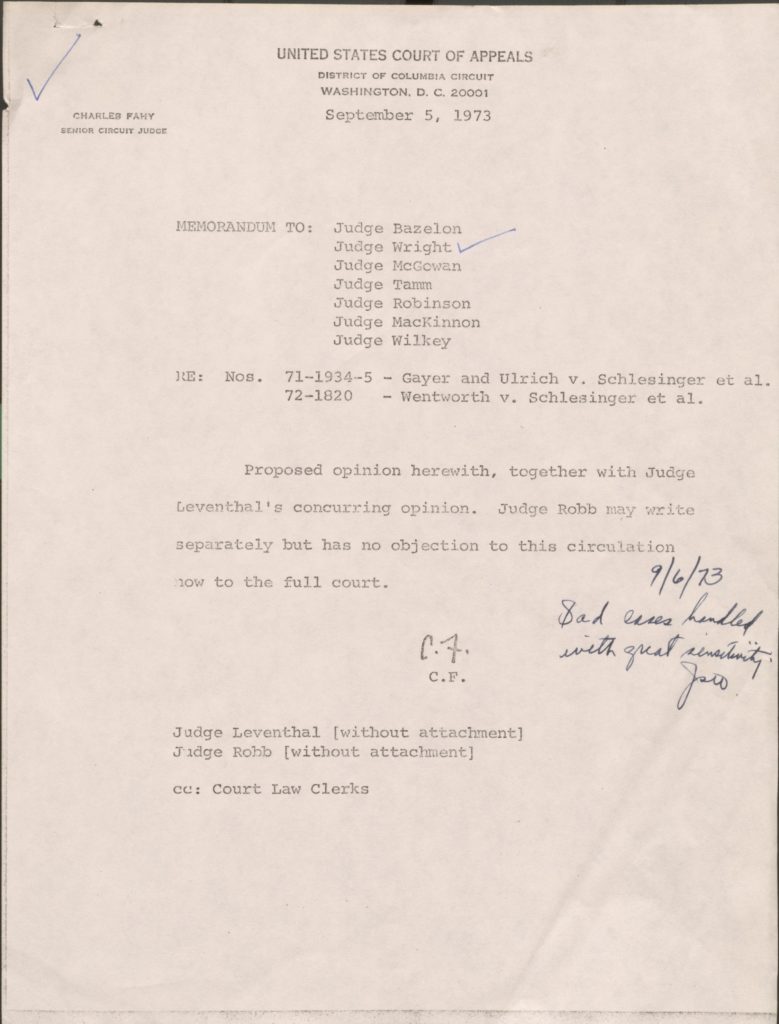

For his part, Fahy recognized the opinion lacked specificity in regard to providing guidelines, but he believed that it was progress. “[A]s a reviewing court, rather than as an initial decisional body, we should not try in the abstract to put the administrators of the program into definite guides at this stage of what I consider a developing process in the law.” Judge J. Skelly Wright, already famous for his work desegregating New Orleans’s schools and public spaces as a District Judge in Louisiana before being appointed to the D.C. appellate court in 1962, wrote on one circulated memorandum: “Sad cases handled with great sensitivity.[22]

In the end, in his decision, Fahy stuck to his points above both defending the government’s clearance regime while also critiquing it. To the former, Fahy found “no lack of fair procedure” in the process, even quoting Judge Warren Burger’s dissent in Scott v. Macy: “Do my colleagues now decide sub silentio that the government must employ sex deviates or that the efficiency of public service is promoted by doing so?” Footnote #14 in which he described homosexuality as “a life of sexual perversion,” that might be worthy of discrimination, served as further evidence of Fahy’s doubts regarding claims of equal protection.

However, the judge agreed that the questioning of both Wentworth and Ulrich did exceed reasonable bounds. Fahy reinstated both men’s clearance but noted the government could “initiate new proceedings to be conducted consistently” within the guidelines established by the decision. For Gayer however, Fahy made a distinction between his refusal to answer the questions put to him as compared with Ulrich and Wentworth, writing that Gayer’s failure to answer any of the questions “other than acknowledgment of his homosexual life, is fatal to his challenge …” Instead, Fahy remanded Gayer’s case to the administrative level so that Gayer might respond to the government’s questions.

Though he signed on to Fahy’s opinion, Leventhal issued a concurrence that reiterated his concern regarding a possible per se rule, asserted limitations on government interrogations into employees private lives and observed that the of enforcement of sodomy laws rendered them legally unmeaningful.

A dissenting Judge Robb agreed that the program did not suffer from a per se rule, that homosexual activity served as a determining factor in eligibility, and that the government remained well within its rights in questioning applicants regarding their sexual lives, but that such inquiries should be “no more extensive than reasonably necessary.” In contrast, however, Robb found the questions asked of Gayer, Ulrich, and Wentworth all acceptable. “I agree that some of the questions put to Mr. Wentworth were unpleasant and indelicate. They would not have been acceptable in a drawing room, but having announced to the world that he was proud to be homosexual Mr. Wentworth should not have been offended or shocked by questions seeking to determine precisely what he meant by his description of himself.” Instead, Robb argued for reversing all three judgments in favor of the government examiners.

In the conclusion of his 1974 letter to Fahy, Gayer asked that Footnote 14 be amended such that it focused not on alleged sexual perversion but rather on the perversion of civil rights by the nation’s courts “…or else that [the government’s] concern with a gay life style must be held to be illegal as discriminatory, as seems to be the suggestion …”[23] A sentiment that would gain increasing credence. Upon receipt, Fahy circulated the letter adding he intended to enter it into the court record, but not respond. Judge Robb concurred, adding that “the content and tone” of Gayer’s letter did not “suggest … that he is a likely candidate for admission to the bar.”

Gayer did receive his SECRET security level clearance in 1975, following the aforementioned Otis Tabler, but only after he responded to the very questions for which he had refused to answer in 1969, endured a re-investigation, and threatened yet another lawsuit. While thankful for his clearance, Gayer remained vigilant. “Has the DOD changed its policy on homosexuals? That’s anybody’s guess,” he noted in a 1975 press release.[24] Moreover, Gayer had entered law school at Hastings College in San Francisco and contrary to Robb’s assertion, eventually passed the bar in 1975 going on to represent numerous members of the LGBTQ community in discrimination cases, including the federal courts.

[1] Richard Gayer to Charles Fahy, letter, July 14, 1974, Box 76, Charles Fahy Papers, Manuscript Division Library of Congress.

[2] Eric Cervini, The Deviant’s War: The Homosexual v. The United States of America (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2020), 239.

[3] Cervini, The Deviant’s War, 286.

[4] Ryan Reft, “Military Industrial Sexuality: Urban California, Gay Liberation and Military Industrial Complex,” Boom California, December 20, 2018, https://boomcalifornia.org/2018/12/20/military-industrial-sexuality/ .

[5] RPC to Judge Fahy, Memorandum: Re: Wentworth v. Laird, No. 72-1820, January 23, 1973, Box 76 Charles Fahy Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress; Katherine M. Graham, “Security Clearances for Homosexuals,” Stanford Law Review, vol. 25 no. 3 (February 1973): 420, footnote #114.

[6] RPC to Judge Fahy, Memorandum Re: Gayer v. Laird, No. 71-1934, Ulrich v. Laird, No. 71-1935, Wentworth v. Laird, No. 72-1820; Cervini, The Deviant’s War, 311. The government frequently stuck to its increasingly thin argument that each man remained vulnerable to blackmail despite their open admittance of their sexual orientation. For example, in one of Wentworth’s subsequent hearings following his initial denial the examiner argued that he had not “proven he had actually sent his news releases” and therefore remained a target for blackmail.

[7] Cervini, The Deviant’s War, 254, 211

[8] Cervini, The Deviant’s War, 311; RPC to Judge Fahy, Memorandum Re: Gayer v. Laird, No. 71-1934, Ulrich v. Laird, No. 71-1935, Wentworth v. Laird, No. 72-1820, Box 76, Charles Fahy Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

[9] Cervini, The Deviant’s War, 312.

[10] RPC to Judge Fahy, Memorandum Re: Gayer v. Laird, No. 71-1934, Ulrich v. Laird, No. 71-1935, Wentworth v. Laird, No. 72-1820, Box 76, Charles Fahy Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. “Consequently, he was notified that his clearance was suspended for his wilful [sic] failure to answer the interrogatories which prevented the Screening Board from making a finding that it would be consistent with the national interest for him to be given a clearance,” noted an appellate clerk’s memorandum summarizing the issues of the case; Katherine M. Graham, “Security Clearances for Homosexuals,” Stanford Law Review, vol. 25 no. 3 (February 1973): 411.

[11] Charles Fahy to Harold Leventhal, June 21, 1973, Box 81, Harold Leventhal Papers, Library of Congress.

[12] RPC to Judge Fahy, Memorandum: Re: Wentworth v. Laird, No. 72-1820, January 23, 1973, Box 76, Charles Fahy Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[13] Graham, “Security Clearances for Homosexuals,” 424.

[14] Harold Leventhal to Charles Fahy, Memorandum: Re: 71-1934, Gayer v. Secretary of Defense, May 29, 1973, Box 76, Charles Fahy Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress; Charles Fahy to Harold Leventhal, Memorandum: Re: No. 71-1934, Gayer v. Secretary of Defense and related cases of Wentworth and Ulrich, June 6, 1973, Box 76, Charles Fahy Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress; for Adams v. Laird, see also Graham, “Security Clearances for Homosexuals,” 424.

[15] Harold Leventhal to Charles Fahy, Memorandum: Re: 71-1934, Gayer v. Secretary of Defense, May 29, 1973 Box 76, Charles Fahy Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. He continued noting, “and would require us to consider the proper scope of the ‘criminal acts’ criterion when it is virtually admitted that there are heterosexual activities that are forbidden by various state criminal laws that are not made per se grounds for dismissal.”

[16] Daniel Hurewitz, Bohemian Los Angeles and the Making of Modern Politics (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2007), 17-18, 272.

[17] Harold Leventhal to Charles Fahy, Memorandum: Re: 71-1934, Gayer v. Secretary of Defense, May 29, 1973, Box 76, Charles Fahy Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[18] Charles Fahy to Harold Leventhal, Memorandum: Re: No. 71934 – Gayer v. Secretary of Defense and related cases of Wentworth and Ulrich, June 6, 1973, Box 76, Charles Fahy Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[19] Harold Leventhal to Charles Fahy, Memorandum: Re: 71-1934, Gayer v. Secretary of Defense, May 29, 1973, Charles Fahy Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

[20] Charles Fahy to Harold Leventhal, Memorandum: Re: No. 71934 – Gayer v. Secretary of Defense and related cases of Wentworth and Ulrich, June 6, 1973, Box 76, Charles Fahy Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress; Charles Fahy to Harold Leventhal, Memorandum: Re: No. 71934 – Gayer v. Secretary of Defense and related cases of Wentworth and Ulrich, June 6, 1973, Box 81, Harold Leventhal Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[21] Harold Leventhal to Charles Fahy, Memorandum Re: 71-1934, Gayer v. Secretary of Defense, June 19, 1973, Box 76, Charles Fahy Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[22] Charles Fahy to Harold Leventhal and Roger Robb, Memorandum: Re: Nos. 71-1935-5-Gayer et al. v. Secretary of Defense, 72-1820 – Wentworth v. Secretary of Defense, June 22, 1973, Box 76, Charles Fahy Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress; J. Skelly Wright, handwritten annotation to Memorandum Re: Nos. 71-1934-5 – Gayer and Ulrich v. Schlesinger et al., September 5, 1973, Box 76, Charles Fahy Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[23] Richard Gayer to Charles Fahy, letter, July 14, 1974, Box 76, Charles Fahy Papers, Manuscript Division Library of Congress

[24] Richard Gayer, Press Release: “Gay Security Clearance Victory: Gay Activist is Found Eligible for Secret Clearance after Five Years of Litigation,” September 9, 1975, Frank Kameny Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.