In the 2008 film, Frost/Nixon, James Reston, played by Sam Rockwell, looks into the camera and says of President Richard M. Nixon, “His most lasting legacy is that today any political wrongdoing is immediately given the suffix ‘-gate.’” Whether apocryphal or not, the quote is both incisive and superficial.[1]

On the one hand, Reston was correct. Every subsequent scandal since Watergate has been viewed and framed by, the 1973 break-in and cover-up often even down to its name and the aforementioned suffix. “The Watergate Affair has been called the greatest political scandal of the twentieth century, the standard against which all subsequent scandals have been judged,” writes historian Geraldo Cadava. “It caused many to lose faith in government, led to campaign finance reform … and drove Americans to demand greater transparency in politics, which led to broad transformations that reshaped the cultural and political landscape for decades to come.”[2] Though historians have questioned how much transparency improved and government corruption declined after the scandal, much of Cadava’s point remains true, a testament to Watergate’s enormous influence.

“Nixon’s continued impact on the presidency and the upcoming fiftieth anniversary of the scandal next year, are why the Manuscript Division recently published Richard Nixon’s Political Scandal: Researching Watergate in the Manuscript Collections at the Library of Congress, an exhaustive review of the division’s holdings pertaining to Watergate.”

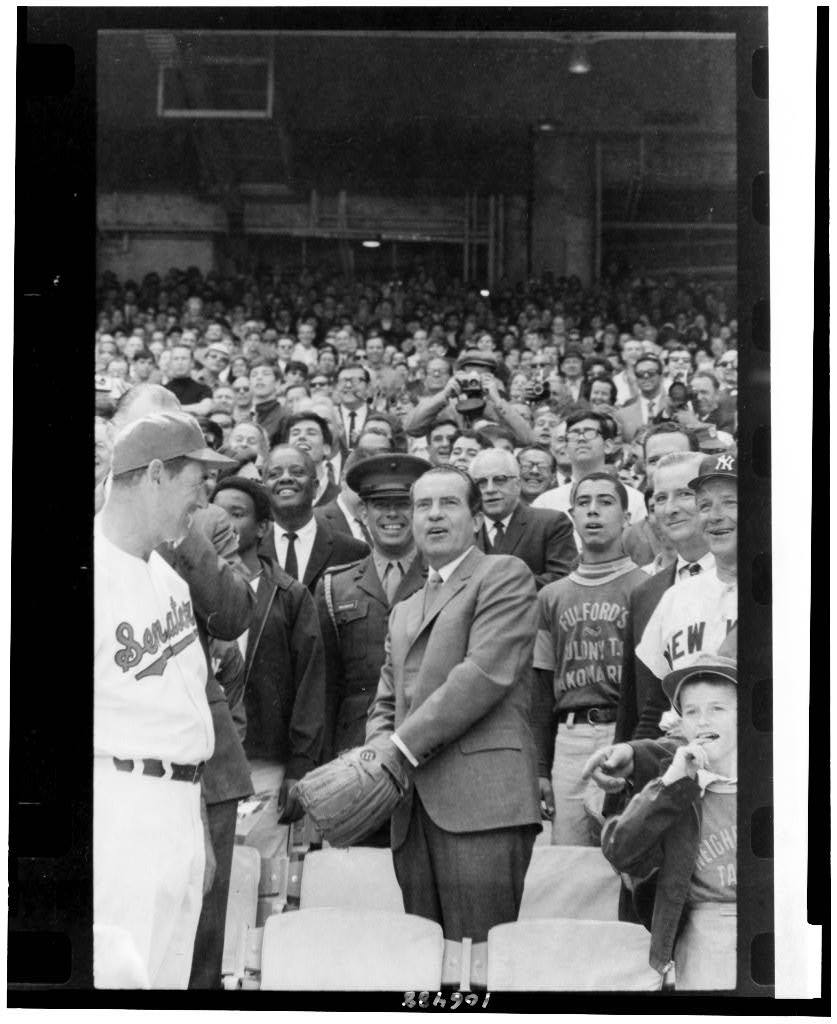

Rockwell’s Reston was speaking before Nixon’s proverbial “long tail” of political rehabilitation began. Twenty years after his resignation, historian Richard Norton Smith described Nixon not as a disgraced president but rather “a White House adviser, prolific author and much-sought-after interview.”[3] While Nixon’s reputation had benefitted from his death a year earlier, the late president played a critical role in reestablishing his own legitimacy. Indeed, the Manuscript Division collections at the Library of Congress are replete with post-Watergate correspondences from Richard M. Nixon to figures such as Jack Kemp (cabinet official and U.S. representative from New York) and Donald T. Regan (White House chief of staff and cabinet official) among numerous others.

Although Watergate remains the issue/event that most Americans associate with Nixon, perhaps its use as a synecdoche for the Nixon administration misses the mark. As Joan Hoff argues in her 1993 work, Nixon Reconsidered, the former president’s legacy consisted of much more than Watergate despite the scandal, “his name continues to dominate public awareness as few presidents [of the twentieth century] have … No better case study of the strengths and weaknesses of the modern presidency exists than the administration of Richard Nixon.”[4]

Nixon’s continued impact on the presidency and the upcoming fiftieth anniversary of the scandal next year, are why the Manuscript Division recently published Richard Nixon’s Political Scandal: Researching Watergate in the Manuscript Collections at the Library of Congress, an exhaustive review of the division’s holdings pertaining to Watergate. The guide serves several roles; a tool for researchers hoping to dig deeper into the Watergate narrative; a resource for high school and college students looking into primary documents for research papers but also historiographical insights into the scandal and those that experienced it be they judges, justices, journalists, members of congress, congressional staff, or administrative officials. Finally, for academics and journalists searching for new narratives or interpretations of the scandal and the larger administration, the guide provides a means to these discoveries. Collections such as the newly acquired L. Patrick Gray III Papers, the addition of Judge John J. Sirica’s Watergate era diary to his papers already housed in the division and the recently opened papers of Meg Greenfield and Ronald L. Ziegler among numerous others provide opportunities for new insight and reflection on not only the scandal, but Nixon and the broader era.

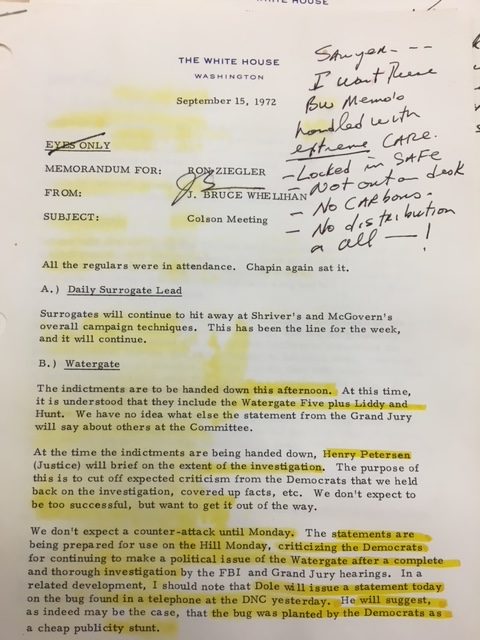

What might an inquisitive researcher find? The Ronald Ziegler Papers feature several folders documenting the 9:15 White House Attack Group which historian Joan Hoff describes as a series of meetings during the summer of 1972 between Chuck Colson, “[H.R.] Haldeman, [John] Ehrlichman, and press secretary Ziegler in so called ‘nine fifteen [in the meetings] … to plan daily public relations tactics.”[5]

Strategies of the group included accusing Democrats of bugging themselves: “[Robert Dole] will suggest, as indeed may be the case, that the bug was planted by Democrats as a cheap publicity stunt”; and sending Black Nixon supporters to Vice Presidential candidate Sergeant Shriver’s “homestead in Maryland” where they were to distribute “a brochure prepared by some unknown and unsuspecting foundation,” about “the Shriver family, its slaves and Shriver’s confederate ancestors. The media are being encouraged to come along.” [6]

While the division holds the papers of many judges from both the United States District and Appellate Court for the District of Columbia, featured in our library guide, The Federal Paper Chase: Judges’ Papers in the Manucript Division, it has added to its John J. Sirica collection by recently acquiring the judge’s diaries from 1973 to 1977. In his diary, he recounts various episodes from Watergate related trials such as Nixon advisor, John Ehrlichman “drawing sketches of Hammurabi, Moses, Solon, and Justinian from the white marble statues built into the marble wall in back of the judges’ bench representing the famous lawyers of ancient times.” Sirica conveys his disappointment in lamenting President Gerald Ford’s pardon of Nixon and its effect on the public: “It’s unfortunate that Pres. Ford announced his pardon of Richard Nixon when he did because it’s making it extremely difficult to get a jury. The people being questioned feel it is unfair to try the five defendants in view of the fact that Nixon was granted a pardon.”[7]

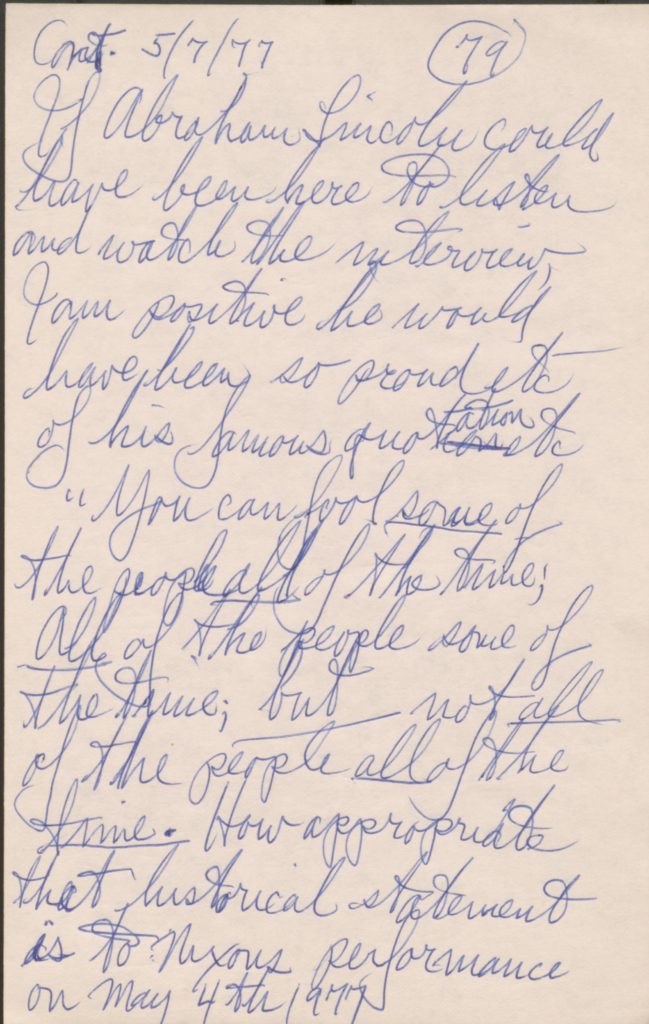

Sirica also opines about journalistic coverage. In one passage, he forgives William Safire for his harsh bromides, “He has his job – I have mine and you can’t please all the people. I guess reporters have the same problem – they either get praised or criticized.” In another entry, Sirica celebrates Anthony Lewis, for his laudatory column about him in late February of 1975 that repudiated Sirica’s critics. “I thought it was an excellent statement by him. I am attaching a Xeroxed copy of the article to this memo. I also wrote the article out in longhand and I subscribe to practically everything Lewis said,” Sirica predictably confided. In yet another, he discusses a dinner party with journalist Nancy Dickerson. [8]

Later, Sirica captures Watergate’s impact on governments around the world. After meeting with a Japanese judge who tells him the scandal had led to greater governmental transparency in other nations. Sirica argues, based on additional conversations with other international figures that “not only Japan, but other countries as well, now expect honesty and integrity from their public officials. One of the reasons, [Japan’s] Prime Minister was replaced so quickly was due to Watergate.” Of course, Sirica’s papers extensively document the affair’s litigation including docket books, memoranda, correspondence, transcripts, briefs, and other legal documents from the various Watergate related trials over which he presided. [9]

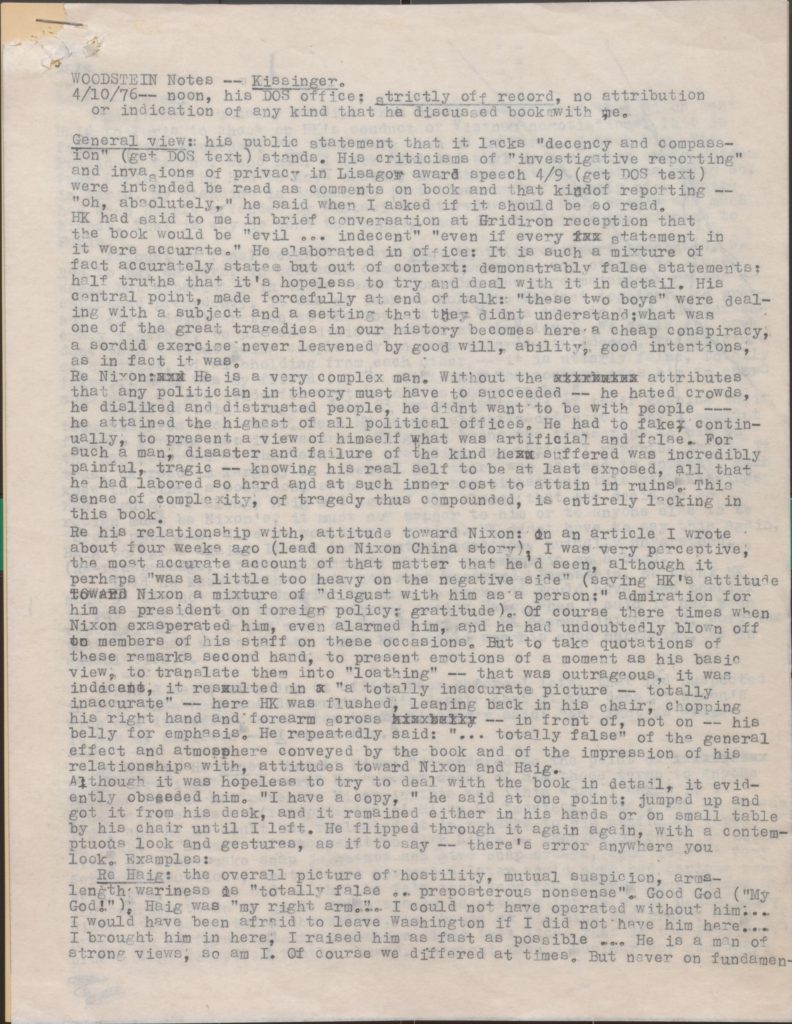

Enterprising researchers will discover in the papers of New Republic journalist John Osborne, described by historian Rick Perlstein as THE White House correspondent of the era, interview notes, many off the record and on deep background, with numerous Nixon officials including Patrick J. Buchanan, Diane Sawyer, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Ronald Ziegler, and Henry Kissinger among others.[10]

In six pages of single-spaced interview notes, Osborne captures the reflections of a disgruntled Henry Kissinger about Watergate, all of them either off the record or on background without attribution. The New Republic journalist spoke with an aggrieved Secretary of State in April 1976, following the publication of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s Final Days. Unsurprisingly, Kissinger denigrates the book telling Osborne, it would “be evil … indecent even if every statement in the book were accurate,” decrying the work, paraphrased by Osborne, as a series of “demonstrably false statements,” “half-truths” and a “mixture of fact accurately stated but out of context.” “’These two boys’, he tells Osbourne, “were dealing with a subject and setting that they didn’t understand.” [11]

When interviewing individuals in person, Osborne’s talents as an observer shine through as well. While Kissinger discusses the book’s depiction of his relationship with Nixon, notably accusations that he loathed the president, Osborne describes the scene, “here HK was flushed, leaning back in his chair, chopping his right hand and for[e]arm across – in front of, not on – his belly for emphasis. He repeatedly said: ‘totally false’ of the general effect and atmosphere conveyed by the book …” Similar interviews with various administration officials from the Ford, Carter, and first term Reagan presidencies can be found in the collection.[12]

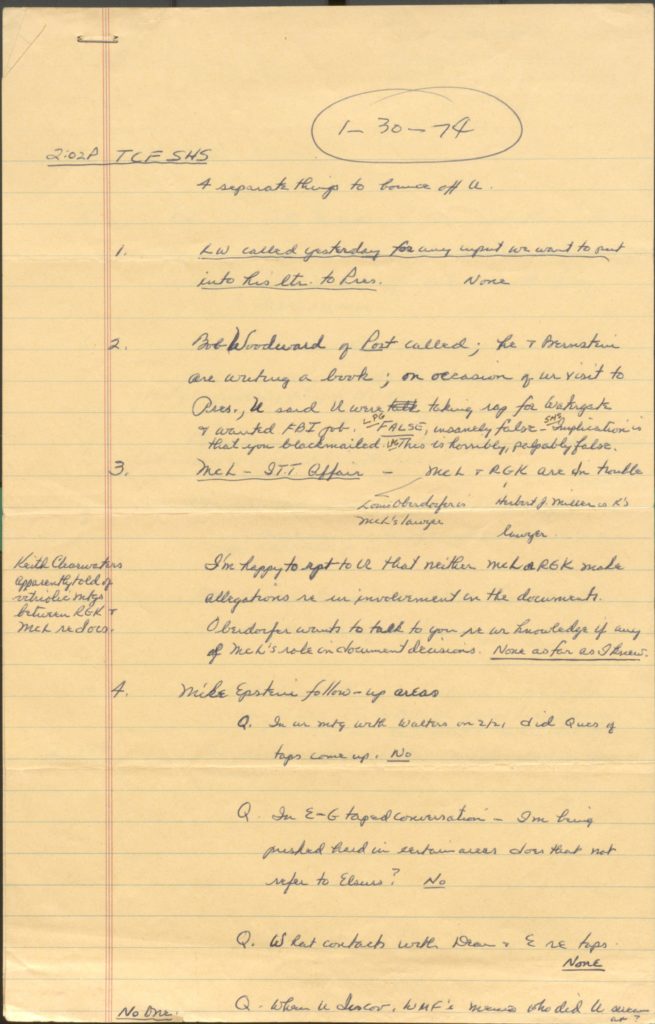

Unsurprisingly, Kissinger was not alone in his vehement disagreement with the two famous reporters. Former acting director of the F.B.I., L Patrick Gray expressed his own incredulity when in late January of 1974, Woodward and Bernstein contacted him in regard to the scandal as they were amidst writing All the President’s Men. “Woodward of Post called; he and Bernstein are writing a book; on occasion of [your] visit to President, he said [you were] taking the rap for Watergate [and] wanted FBI job.” To which Grey writes: “FALSE, insanely false.” Writing down his lawyer’s comments, “Implication is that you blackmailed,” to which Gray once again dismissed in his handwriting as “horribly, palpably false.” [13]

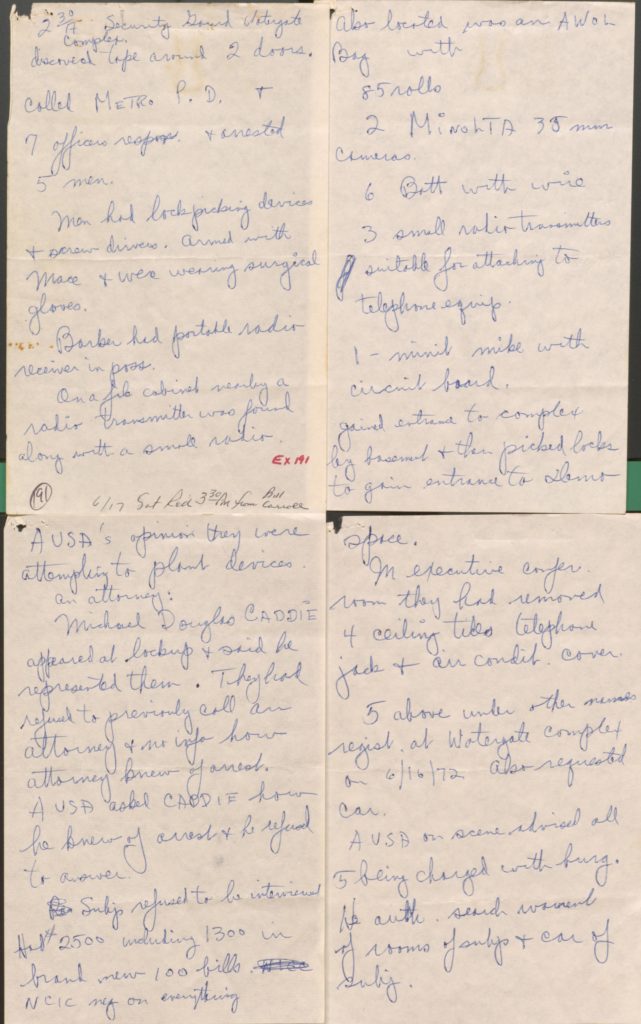

Gray’s papers also feature the first months of investigation into the scandal including his handwritten notes documenting details of the break in: “Security guard [at the] Watergate Complex discovered tape around 2 doors, called Metro P.D. [and] 7 officers respond [and] arrested 5 men. Men had lockpicking devices and screwdrivers. Armed with mace [and] were wearing surgical gloves.”[14] Subject to post-Watergate litigation, Gray’s papers bulge with not only with insights regarding the scandal but also documents from his nine months overseeing the F.B.I. as acting director from May 1972 to March 1973. In addition to Watergate which is prominent, other issues of the day such F.B.I. reform, Wounded Knee/AIM, the Weather Underground, the I.I.T. controversy, and policing among others.

Although Watergate was a turbulent and sometimes frightening time, America’s government survived the crisis. In a speech to staff the day after Nixon resigned, Ambassador to India Daniel Patrick Moynihan–whose papers are housed in the Manuscript Division and featured in the guide–stated: “…ours is a Government of laws not of men. . . . The corrective mechanisms of the system which seemed to be in good working order, the strong and moral men of the present administration . . . are coming to be valued for the integrity they sustained in murky times.” He continued: “Strong and ethical men in other institutions, the Congress, the courts, the press, are seen for what they mean.”[15] The papers of many of the individuals to whom Moynihan referred and who kept the government in tact are held by the Library of Congress’s Manuscript Division and described in Richard Nixon’s Political Scandal: Researching Watergate in the Manuscript Collections at the Library of Congress.

[1] Frost/Nixon, Directed by Ron Howard (Universal Pictures, 2008).

[2] Geraldo Cadava, The Hispanic Republican: The Shaping of an American Political Identity from Nixon to Trump (New York: Harper Collins, 2020): 113.

[3] Richard Norton Smith, “The Nixon Watch Continues,” New York Times, October 30, 1994, BR9.

[4] Joan Hoff, Nixon Reconsidered (New York: Basic Books, 1994), 2.

[5] Hoff, Nixon Reconsidered, 308; White House Attack Group meeting notes with Ron Ziegler’s annotations, September 15, 1972, Box 15, Ron Ziegler Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[6] Ibid.

[7] John J. Sirica, diary entry, October 9, 1974, Box 124, John J. Sirica Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[8] John J. Sirica, diary entry, February 24, 1975, Box 124, John J. Sirica Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[9] John J. Sirica, diary entry, February 24, 1975, Box 124 John J. Sirica Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[10] Regarding Osborne’s status, see Rick Perlstein, Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America (New York: Scribner, 2008), 389.

[11] John Osborne “Woodstein” interview notes off the record with Henry Kissinger, April 10, 1976, John Osborne Papers, Box 32, Folder 8, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

[12] See John Osborne Papers, boxes 35 (Ford), 45-46 (Carter), and 65 (first term Reagan, 1981).

[13] L. Patrick Gray’s notes regarding Woodward and Bernstein’s reporting, January 30, 1974, Box 47, Folder 4, L. Patrick Gray Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[14] L. Patrick Gray’s notes regarding the June 17, 1972 Break in of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate, June 17, 1972, Box 39, Folder 6, L. Patrick Gray Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[15] Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Speech of August 9, 1974, BoxI:368, Daniel Patrick Moynihan Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.