Dr. Felicity Turner’s book, Proving Pregnancy: Gender, Law, and Medical Knowledge in Nineteenth-Century America was published by The University of North Carolina Press in the fall of 2022. Dr. Turner was kind enough to discuss her new book with The Docket. Here is our conversation.

The Docket [TD]: Readers will take a look at your title and see how contemporary legal and political developments might have influenced you to write about this topic. But the reality is that you’ve been working on this for a while now, first as a graduate student and now as a professor. How did you arrive at this topic and decide you wanted to write this book? Was there a specific moment that comes to mind, or was this more of a gradual historical development?

Dr. Felicity Turner [FT]: This book began, really, in the North Carolina State Archives. I had arrived at graduate school intending to write a dissertation about the post-1960s civil rights movement, but quickly abandoned that idea after I realized that oral history was not my medium. I preferred reading scrawly nineteenth century handwriting. So, in my second year of graduate school, I headed over to the state archives and started searching for cases of infanticide. I wasn’t really sure what I was going to do with them. But I just wanted to know if there was enough for any kind of larger project to be feasible.

Over time, I became known as the person who was researching infanticide in the nineteenth-century United States. And so, colleagues, and colleagues of colleagues (people I had never met) from all over sent me records of infanticide they had stumbled across in their archival journeys.

But, after all that, the word “infanticide” is not in the book’s title. There was not an “a-ha” moment when I decided to jettison the word. Somewhere along the way, as I was revising the dissertation to transform it into a book, I realized the book was about the bodies of women, far moreso than the corpses of infants. More particularly, the book is about knowledge of women’s bodies, and how who possessed and laid claim to that knowledge changed over time.

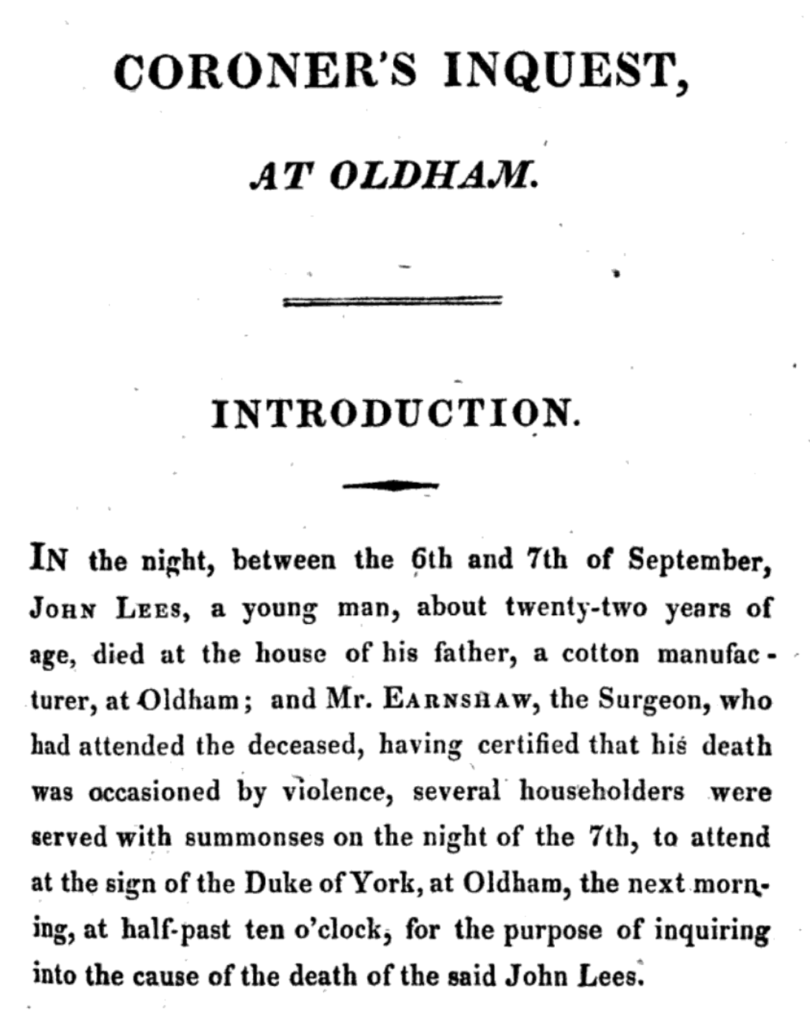

TD: In the introduction you spend some time discussing the incredibly rich sources that form the heart and soul of this book.[1] Here you introduce the importance of inquests and throughout the book return to the testimony presented in these investigations to give readers a granular sense of what these sources were like. Why do you think these inquests came to occupy such an important role?

FT: The inquests came to occupy such an important role because, in most cases, I don’t have the luxury of trial testimony, if indeed there was a trial (as opposed to a plea). That means I don’t know what was said in courtrooms. For most cases, I usually have one or two pages of documents. Those two pages include indictments, which can be very formulaic and lists of witnesses, for example. If I’m really lucky, I can find out the outcome of a case by looking through court dockets or minute books, if any of those records survived. Beyond that, I might find the outcome in a newspaper report. So the inquest testimony, as mediated through the hand of the person who wrote it down (presumed to be both white and male), became my most important window into what happened in these cases.

As Laura F. Edwards (amongst others) has observed, inquests are so important because they are distinct legal forums in which anyone—regardless of status—can speak.[2] Enslaved people could provide testimony about a white woman; free Blacks could testify as to the actions of a white man. This contrasted with courtrooms where enslaved people and free Blacks could not testify against whites in a criminal trial. Children could also speak in inquests, so I have a number of inquests where the testimony of young girls proved important. Although an inquest jury always consisted of white males, these particular sources possessed a particular value for me because of the range of witnesses who could testify.

TD: There’s been some really fascinating literature on the intersection of histories of gender, medicine, law, and power, such as Susanna Blumenthal’s Law and the Modern Mind: Consciousness and Responsibility in American Legal Culture and Deirdre Cooper Owens’ Medical Bondage: Race: Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology, to name a couple of examples.[3] How do you see Proving Pregnancy as building on and contributing to this literature? And what do you think is specifically new in your book’s argument?

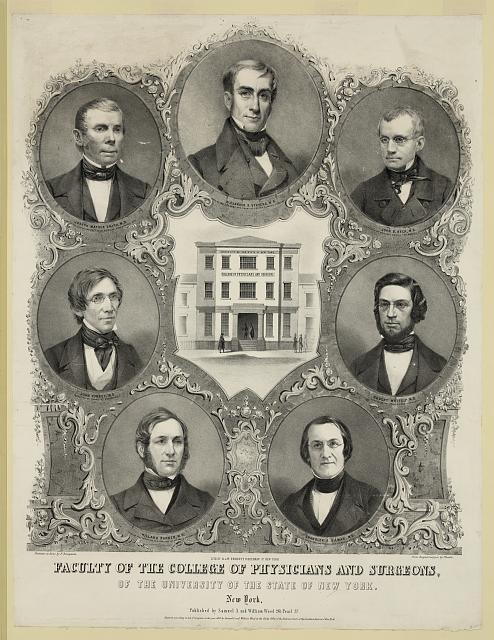

FT: Much of the existing literature, including the impressive work cited here, is about the slow evolution toward the professionalization of law and/or medicine in the nineteenth-century U.S. This work traces how experience as a lawyer or as a medical practitioner came to be displaced in favor of formal training within an institutional setting. Susanna Blumenthal, in particular, focuses on the development of a particular field known as “medical jurisprudence” which was very important to both nineteenth-century physicians and lawyers as they endeavored to establish their status and assert authority during this time. Further, much of the recent literature in the history of medicine—particularly at the intersection of gender and race such as that of Deirdre Cooper Owens—has worked to complicate narratives of power, illuminating how the knowledge of free Blacks and enslaved women contributed, in complex ways, to the growth of medical professionalization.

Most of this scholarship has, however, focused upon state legislation, legal or medical treatises, medical technology, and decisions in state appellate courts. Proving Pregnancy, then, adopts a different approach, arguing that what happened in local communities in legal forums such as inquests merits close attention as changes in state law that elevated the status and importance of physicians made little difference if everyday people didn’t accept the authority of male doctors in matters of childbirth. This then explains, in turn, why the particular sources I use became so important. When juries of inquest routinely began to request that physicians physically inspect the bodies of white woman suspected of having been pregnant (a transition that can really only be traced through a close analysis of inquests), this signified a very important shift in understandings about how people understand the authority of physicians in daily life.

TD: Medical science and legal rights are both things that contemporary readers tend to associate with the expansion of women’s rights, especially in thinking about the legal history of the late twentieth-century United States. But in your argument, both play a very different role. Can you explain how physicians professionalization and “medicalization” in nineteenth-century America actually hindered ordinary women’s lives?

FT: That is a great question as this transition is really central to the book’s argument. As I argue, the process of professionalization was problematic as it marginalized existing claims by women to possession of medical knowledge, particularly in relation to pregnancy. So, in that sense, this change was—as I, and others, have argued—less than ideal for women, as they had historically laid claim to such knowledge and identified it as a source of authority and power.

It’s important to keep in mind, though, that this transition was complex. As I demonstrate in Proving Pregnancy (chapter five), white, male physicians often rode into town and reexamined the evidence from inquests where the community had already decided the mother was guilty of killing her newborn infant. The findings of those physicians that the infant had died by some natural cause or by accident then transformed the outcome for the accused woman. The community may still have held a low opinion of the single woman who had secretly given birth to an illegitimate child, but the (white, male) physician actually saved her from a trial and potential jail term.

What makes this transition even more complex is that we can’t actually assume the physician was accurate in his diagnosis “just because” he was a physician. Medicine still got a lot of things wrong in those days (as it does now). But what had changed is that the community now accepted the word of the physician as more important than their own consensus about the cause of death, as informed by the medical expertise and experience of women. And while I emphasize, in my narrative, that the changes meant more complicated outcomes for women, the extension of this argument is that—eventually—this meant more problematic outcomes for males without access to power too.

TD: If we can return for a moment to the present, do you think that your book does in fact help us understand contemporary legal and political events in the United States?

FT: Given that I write about infanticide, I acknowledge that the most obvious parallel in contemporary terms is reproductive justice. And whether we like it or not, questions about reproductive justice are very much part of the American legal and political landscape today.

I think what the past shows us is that people understood the issues associated with reproductive justice in very different terms in the nineteenth century. In the first half of the nineteenth century United States, questions about infanticide were most frequently adjudicated within and amongst local communities. That meant processes and outcomes were more individualized, in spite of what “the law” might have said about infanticide. In antebellum rural North Carolina, for example, suspected cases of infanticide were frequently resolved at an inquest, with many never making it beyond that level. Other cases, in turn, might result in an indictment, and eventually a verdict at trial, but how each case was resolved was largely contingent upon circumstances individual to each accused woman.

I also think one of the more important things my book demonstrates is that ordinary, everyday people possessed what we might think of today as very nuanced and sophisticated understandings of pregnancy and childbirth, particularly in the first half of the nineteenth century. As I discuss in the second chapter of my book, people knew the difference between abortion and infanticide. They did not rely on doctors to explain things to them about women’s bodies at inquests because they trusted experienced women in the community to be able to do this for them. This then helps explain why local communities made decisions at an individualized level, rather than relying on male physicians who had been trained in out-of-state medical colleges.

But once physicians organized and assumed authority to claim knowledge of obstetrics and pregnancy as their exclusive province, the legal and political landscape in relation to reproductive justice changed, albeit gradually. And we see the ramifications of that today.

TD: To end on a lighter topic: you are an extremely well-traveled person, but you originally hail from Australia. Tell us about some of your favorite places back home!

FT: All of my favorite places are in Melbourne, the city of my birth. I usually try and visit to catch up with my family every few years, although COVID put a bit of a dent in that.

For good coffee, I recommend Pellegrini’s Espresso Bar at the top end of Bourke Street or Mario’s on Brunswick Street in Fitzroy. Both are institutions. Back in the day when Jerry Seinfeld was someone (remember him?), Mario’s famously declined to let him make a reservation when he was visiting town. They didn’t take reservations back then and that policy has thankfully never changed, no matter how famous the person attempting to make the reservation may be.

Beyond coffee spots, one of my favorite places in Melbourne is Flinders Street Station, at the corner of Swanston and Flinders Street, particularly in the winter at rush hour, when it’s dark, the lights are on, and the intersection is packed with pedestrians running to catch a train or a tram. It’s like an entire cross-section of Melbourne is crammed into that small space for an hour or two. Although it’s smelly, noisy, and crowded, it always seems to me that you can feel the heartbeat of Melbourne for these few hours every night.

[1] Felicity Turner, Proving Pregnancy: Gender, Law, and Medical Knowledge in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2022), 12-13.

[2] Laura F. Edwards, “Status Without Rights: African-Americans and the Tangled History of Law and Governance in the Nineteenth-Century U.S. South.” American Historical Review 112 (2007): 372-73.

[3] Susanna L. Blumenthal, Law and the Modern Mind: Consciousness and Responsibility in American Legal Culture (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016); Deirdre Benia Cooper Owens, Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2017).