In nineteenth century France, women organized to demand the right to sit on criminal juries as a matter of fairness and equity. Activists argued that a jury of “peers” required that female defendants, at least, should be judged by female jurors, or else justice was denied. After reformers tried the usual political routes – such as sending petitions to the Chamber of Deputies and drumming up public support, a socialist deputy proposed a bill in 1901. This bold legislative act was not successful but demonstrated the political power of women to catalyze change even though women were formally outside the political process as yet-to-be enfranchised citizens. Although French women would not vote until 1944, feminist activists from the nineteenth century articulated a political platform intent on fundamentally altering society to render it less disadvantageous to women especially in the areas of family law, economic opportunities, and civil and political rights.

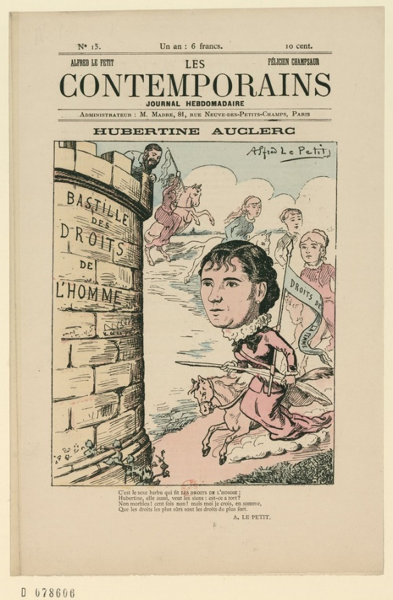

These activists were engaged in a battle of words, as reflected in the cartoon of Hubertine Auclert astride a horse carrying her quill and the standard of “droits de la femme,” (women’s rights) endeavoring to break through the bastille of “des droits de l’homme” (men’s rights). In 1882 Auclert began using the term “féministes” in her critique of marriage laws and noun féminisme in her newspaper La Citoyenne.[i] The cartoon, like too many scholarly works, omits the men who were important allies in this fight, including deputies who introduced bills or writers who defended women’s rights and opportunities. Female and male feminists recognized that the promise of democracy was unfilled when the enjoyment of its rights was gender-exclusive.

In my research more broadly, I am challenging the accepted chronology of the origins of “legal feminism,” that is, the systematic and sustained critique of gender bias in the law combined with egalitarian advocacy to reform institutions of law and jurisprudence, was alive and well in late nineteenth century France.[ii] Feminism as a socio-political movement that challenged male dominance and inequality of power is older than many readers recognize.

French feminist legal arguments were also advanced in the courtroom and in the public advocacy by avocates engagées, female lawyers who took into account the structural ways in which women were disadvantaged through laws, notably in educational and employment discrimination, restrictions on paternity suits and unequal adultery law, political and civil disenfranchisement.

The admission of women to the legal profession in 1900 in France facilitated the advancement of feminist legal arguments in courtrooms, Palais de Justice debates, and the legal press. Maria Vérone, leader of the French Women’s Rights League (Ligue Française pour le droit des femmes) was among the most venerated of her generation for her professional acumen and effective advocacy, including women’s right to stand for municipal election in 1908. The significance of feminist engagements with in legal professions and legal questions raised by women’s participation are among the historical issues I explore with my colleagues from a comparative lens in New Perspectives on European Women’s Legal History (Routledge, 2017).

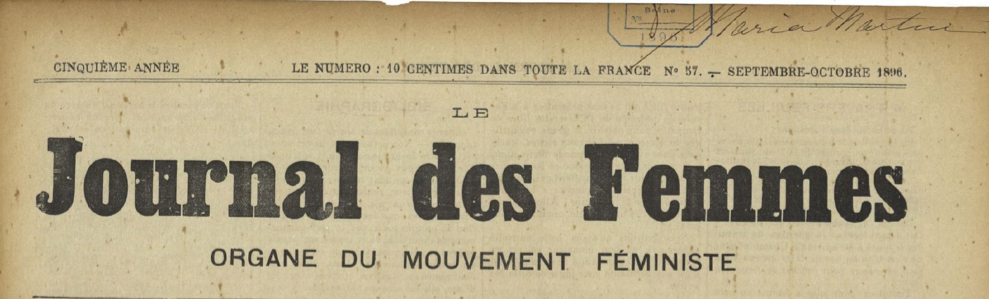

As a historian, I seek to unearth and examine the ways in which men and women have questioned the gendered organization of their society requires looking for different voices. In research for this article in the Law and History Review, I examined traditional political sources including parliamentary debates and committee deliberations, political meeting reports, congress proceedings, published legal treatises, and copies of the burgeoning women’s press including Le Journal des femmes edited by Maria Martin. By 1896 Martin’s journal claimed to speak for the “mouvement féministe.”

The jury féminin project, examined in my LHR article, emerged in the broader context of feminist criticism of socio-political inequalities that were bolstered by legal and judicial structures and practices. From the late nineteenth century, the French movement for women’s rights became organized, created newspapers, and held conferences that reveal their multivalent agendas and strategies designed to reorganize all aspects of society to emancipate women (and children) from the multiple disadvantages of living in republic that privileged wealthy men above all others.

Jeanne Chauvin, a stellar legal student and advocate of educating girls in legal fundamentals, broke the barrier that excluded women from the legal profession. She wrote a thesis on the history of gender bias in the liberal professions in which she exposed the historical construction of gender discrimination and brought to light moments of exceptional action by women in judicial contexts in French history. She argued that equal opportunity to work for men and women would be a rational and “modern” choice, would fulfilled the republican promise, and it would logically extend the educational reforms of the 1880s, ultimately promoting social harmony. Although her court case seeking admission to the lawyer’s oath was denied, she won legislation passed on her behalf and became a lawyer in December 1900. In the early twentieth century, Chauvin and other female lawyers demonstrated their intellectual capacities in hopes of dismantling the prejudicial claims undergirding the system of gender inequality. The jury féminin follows this same pattern of demanding equal treatment and arguing persistently for the advantages of women’s participation in public life.

The cases highlighted by jury féminin brought to life consequences of civil and penal code articles that disadvantaged women in the family. The women’s rights movement sought a single legal and moral standard for the sexes, sought legal reforms in the name of the best interests of children, and for the expansion of democratic ideals. As such, Camille and Hyacinthe Bélilon, the two activist-sisters behind the women’s jury, were involved with other male and female feminists who advocated numerous changes that impacted intimate life such as: paternal authority (puissance paternelle); paternity suits (recherche de la paternité); adultery laws; regulation of prostitution; divorce by mutual consent; infanticide; women’s right to serve as guardians (tutelle); and more.

A critical mass of female lawyers

in the early twentieth century functioned to spearhead the feminist claims to

equal treatment and equal rights under the law.[iii]

Members of the feminist movement and their lawyers promote women’s right to

serve in official judicial capacities in the juvenile courts as well as their

right to right to vote.[iv]

Such activism also had an international dimension. In the interwar years, the militant

of the American Women’s Party endeavored to launch an “equal rights treaty”

modeled on the ERA but intended for approval through the League of Nations.[v]

These generations of activism promoted equality in private and public life so

that republic societies would fulfill their fundamental promise from The Declaration of the Rights of Man and

Citizen (1789) that citizens were “born and remain free and equal in

rights” (Article 1).

[i] See Karen Offen, Debating the Woman Question in the French Third Republic, 1870-1920 (Cambridge University Press, 2018), 157-170.

[ii] Sara L. Kimble, “Transatlantic Networks for Legal Feminism, 1888-1912,” Forging Bonds across Borders. Transatlantic Collaborations for Women’s Rights and Social Justice in the Long Nineteenth Century, special issue of German Historical Institute Bulletin Supplement, edited by Britta Waldschmidt-Nelson and Anja Schüler, vol. 13 (2017), 55-73.

[iii] Sara L. Kimble, Women, Feminism, and the Law in Modern France: Justice Redressed (New York: Routledge, under contract).

[iv] Sara L. Kimble, “No Right to Judge: Feminism and the Judiciary in Third Republic France.” French Historical Studies, vol. 31:4 (Winter 2008): 609-641.

[v] Sara L. Kimble, “Politics, Money, and Distrust: French-American Alliances in the International Campaign for Women’s Equal Rights, 1925–1930.” In Nimisha Barton and Richard Hopkins ed., Practiced Citizenship: Women, Gender and the State in Modern France (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press (January 2019), 219-260.

Sara L. Kimble

Sara L. Kimble