What do we mean when we say the secularization of law? What exactly becomes secular? I puzzled over this question while researching the Bible War which began in Ohio in 1869 when Cincinnati’s public school board voted to end opening the school day with Bible reading. The board was trying to entice into the schools the growing Catholic population which did not use the King James Version of the Bible. Outraged Protestants sued to stop the school board, won an injunction at the local level, and then lost before the Ohio Supreme Court.

Two clauses in the Ohio Constitution of 1851 were at issue in Board of Education v. John D. Minor et al. A guarantee of religious liberty and this: “Religion, morality, and knowledge, however, being essential to good government, it shall be the duty of the General Assembly to pass suitable laws… to encourage schools and the means of instruction.” Did starting the school day with the Bible fulfill the mandate of the religion, morality and knowledge clause? Or violate the religious liberty clause? Did state law require the school board to keep the Bible, remove it, or do as it pleased? Scholars often portray the decision as a landmark in the separation of church and state, but the decision did not end Bible reading in Ohio schools. It declared that state law did not require religious education (or any specific branch of knowledge) and that school boards had discretion over what was taught. This hardly looked like a landmark of secularization.

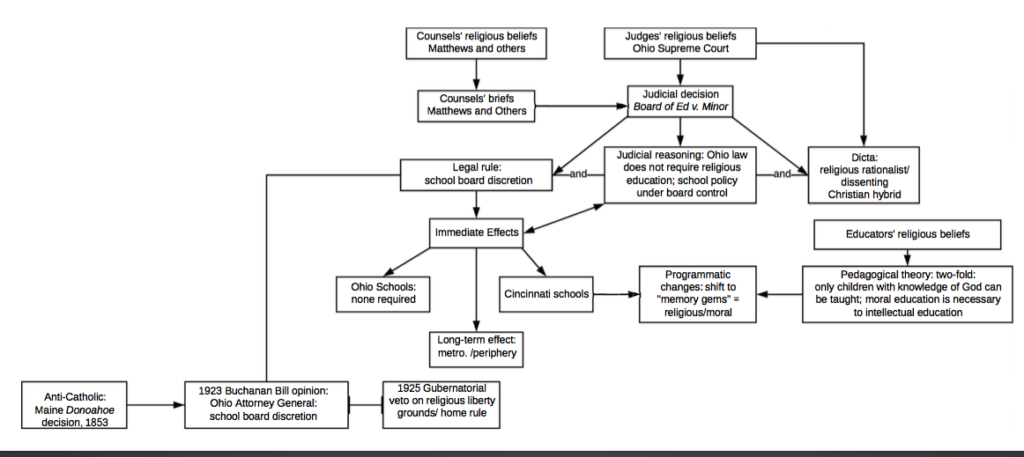

I developed this chart to sort out the levels and spaces where individuals raised and resolved constitutional questions regarding Bible reading in Ohio’s public schools. The boxes represent multiple phenomena: juristic or pedagogical consciousness, as well as levels or spaces where such ideas were expressed in documents or practices. It is a flexible tool that can be expanded at every level, rather than a definitive model. As with other legal scholars, my aim is to place an appellate decision within a wider context. All boxes connect to the Ohio decision which appears at the second level down. The chart moves generally forward in time from the top to the bottom. It captures my insight that, for all the participants, religion framed law. Which is to say, religious beliefs created assumptions about the nature and purpose of law. Religion framed pedagogy as well.

Starting from the top, you see the religious beliefs of the counsel and judges which are then connected to the second level in their briefs and the Ohio decision. Counsels’ religious beliefs framed certain of their legal arguments. Most importantly, lead counsel for the school board Stanley Matthews confessed his Presbyterian faith from the courtroom floor even as he expressed the Christian dissenting tradition’s belief that state involvement damaged religion. Matthews also paired the Protestant belief that a soul achieved spiritual grace by freely accepting Jesus Christ as Savior with the guarantee of religious liberty found in the Ohio Constitution. Compulsion could not produce true religious faith and violated constitutional law.

Moving down from the Ohio decision, you see both the legal rule’s impact to the left and the accompanying dicta to the right. Under the rule, Ohio school districts did not need to do anything immediately or ever: Bible removal was merely a policy option. The limited effect of the rule may explain the repeated re-election of Chief Justice John Welch who delivered the Ohio decision for a unanimous court. Or it may have been his dicta. Welch was an Emersonian, but his decision hybridized his religious rationalism with elements of the Christian dissenting tradition taken from Matthews’ brief, and ignored the more rationalist ideas offered by Matthews’ co-counsel. Anyone expecting to find a fully secular rationale in Minor will be surprised to learn that “Christian republicanism” barred the state from requiring Bible reading according to Welch. But this was dicta.

Most Ohio school districts did not choose to end Bible reading. The immediate and long-term effects which appear below the legal rule were limited. Within the decentralized Ohio educational system, the long-term effect was the continued development of a metropole/periphery divide with larger, heterogeneous cities less likely to require Bible reading in schools than smaller, homogeneous towns. A 1939 study estimated eighty-five percent of Ohio students were still doing Bible reading, a fact that reduces Minor to a not-very-prominent landmark in the secularization of the law.

In Cincinnati, which you see below and to the right of the immediate effects box, educators struggled to comply with the end of Bible reading. Minor collided with two pedagogical theories dating to that the early crusade to create public schools. The first held that only children who respected God, the ultimate Authority, and thus respected all authority, could be taught at all. The second was that intellectual education without moral education was dangerous. These theories fed into the educators’ reaction to Minor. The city’s principals shifted to a program of memorization and recitation. These “memory gems” taught belief in God, in heavenly life after death, and in the religious duty to adhere to virtue. In 1886, the city’s school superintendent identified what had survived the end of Bible reading: “Sacred song, the literature of Christendom [i.e. the memory gems program], and best of all, faithful and fearless Christian teachers, the living epistles of the truth. Against these there is no law.” Cincinnati’s educators did their best to outflank Minor.

Out to the left of the legal rule and dropping down to the bottom of the chart, you see developments in the 1920s when the Ohio Attorney General voiced his official opinion that no law prevented compulsory Bible reading in the public schools while citing the infamous anti-Catholic decision from Maine: Donahoe v. Richards. This facilitated the passage of the Ku-Klux-Klan-sponsored Buchanan bill, which required Bible reading. But the governor vetoed it while praising both “separation of Church and State” and home rule, thus leaving the metropole/periphery divide in Ohio educational practices undisturbed.

The chart ends there, but it might well follow out the long-term effect in Cincinnati. After the U.S. Supreme Court struck down compulsory school prayer as unconstitutional in the early 1960s, a survey of Cincinnati’s schools was published in 1964. All had Christian holiday programming, half had release-time sectarian programs, forty percent had prayer at school assemblies, and a handful still started the day with prayer and Bible reading. In fact, Bible reading continued in some Ohio urban, public schools into the 1970s.

Charting out levels and spaces where constitutional questions were raised and revolved allowed me to integrate the juristic and the pedagogical, consciousness and practices. It allowed me to recognize the power of religious within 19th-century American culture. Although Matthews and Justice Welch both supported an end to Bible reading, they did so by invoking the blessing of Christianity. Religion framed law on both sides of the controversy.