This post traces the development of suits for restitution of conjugal rights (RCR) in Hindu personal law in independent India. Against this backdrop, Nikita Samanta and I subsequently interview Public Interest Litigants who have recently challenged the validity of RCR in the Indian Supreme Court. You can read about the early years of restitution of conjugal rights in India in my Law and History Review article ‘Withholding Consent to Conjugal Relations within Child Marriages in Colonial India: Rukhmabai’s Fight’ where I closely examine the famous Rukhmabai case of the 1880s.

In the late nineteenth century suits for restitution of conjugal rights were transplanted into the marital laws of the native religions in India from English ecclesiastical laws and quickly gained popularity. Such suits were mainly brought about by abandoned wives who hoped that the courts would allow them to regain access to their marital homes or compel their husbands to provide some maintenance, or by husbands who desired that their wives were forced to return home. Since at the time there was no divorce within Hindu marriages and both Hindu and Muslim personal laws allowed for polygamy such suits often exacerbated the legally sanctioned inequalities between the sexes.

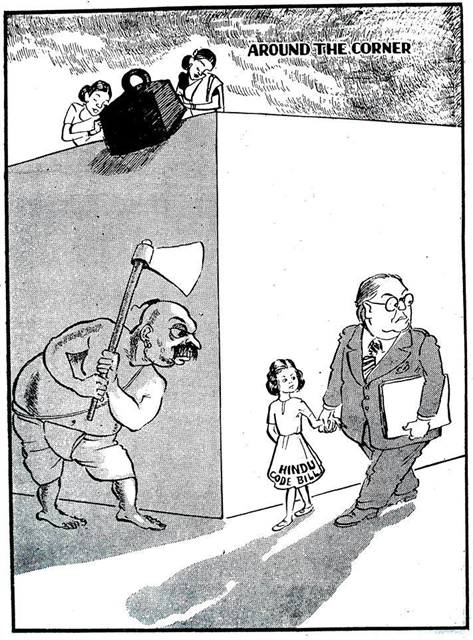

Restitution of conjugal rights ceased to be ‘alien’ when in post-Independent India, such suits were give a statutory footing under sec 9 of the Hindu Marriages Act of 1955. Sec 13 of the same Act introduced divorce within the Hindu marriage. The HMA was one of one of four statutes grouped together as the Hindu Code Bills which sought to reform Hindu personal laws in India. Sec 9 is one of many ways in which the reform failed to live up to its aim of bolstering the rights of Hindu women.

As women started gaining more independence, a discernible shift could be perceived within suits for RCR, where men began to bring about significantly more cases for restitution of conjugal rights than women. Many of these cases focused on ‘weekend marriages’ where the couple lived apart due to work constraints. For instance, in Tirath Kaur v Kirpal Singh (1964) when after her marriage a woman took a job in another town in order to support the family, she found herself faced with a suit for RCR. The lower court found that: “the husband was justified in asking the wife to live with him even if she had to give up service”. The decision was reinforced by the Punjab High Court which argued that “a wife’s first duty to her husband is to submit herself obediently to his authority, and to remain under his roof and protection.”

Long deemed toothless the action of RCR was abolished altogether in England through the Matrimonial Proceedings and Property Act 1970. Meanwhile, in India it went from strength to strength. As middle-class Hindu women became more independent and often had careers before their marriage the courts ordered them to give up their jobs if that is what the husband desired. For instance in Kailash Wati v Ayodhia Parkash (1977) the court held that“[T]he true position in law appears to be that any working woman entering into matrimony by necessary implication consents to the obvious and known marital duty of living with a husband as a necessary incident of marriage.” And in case the woman was in any doubt, the court reiterated that only the husband had the “right to choose and establish the matrimonial home”.

A handful of cases in the mid 1970s across India found in favour of the working wife who wished to live away from her husband, but this was contingent on her still being willing to let her husband exercise his ‘marital rights’ if he wished to do so [Mirchumal vs Smt. Devi Bai (1977)].

The biggest blow to the notion of RCR was dealt by the Andhra Pradesh High Court in 1983 in the case of T Sareetha v T Venkata Subbaiah (1983), where the famous South Indian actress Saritha sought to defend herself against a suit for RCR from her actor husband.

In a ruling reminiscent of Justice Pinhey’s judgment in Rukhmabai’s case in 1885, Justice Choudary reiterated the foreign nature of suits for restitution of conjugal rights before declaring Sec 9 of the HMA in violation of the Indian constitution. Specifically, Art 21 or the right to privacy wherein the court took into account the fact that a wife forced to live with her husband may have to endure ‘humiliating sexual molestation’ and/or be forced to give birth to children she may not wish to have. The court also found that to treat a man and a woman who are inherently unequal in Indian society as equal in front of the law was a violation of Art 14 or the right to equality.

However, the very next year the constitutionality of sec 9 was upheld by the Delhi High Court in Harvinder Kaur v. Harmander Singh Choudhry in 1984, where Justice Rohatgi criticised any attempt to hold personal laws accountable to the constitution: ‘Introduction of constitutional law in the home is most inappropriate. It is like introducing a bull in a china shop. It will prove to be a ruthless destroyer of the marriage institution and all that it stands for. In the privacy of the home and the married life neither Article 21 nor Article 14- have anyplace.’ This interpretation of Sec 9 was upheld by the Indian Supreme Court a few months later in Saroj Rani vs Sudarshan Kumar Chadha (1984).

Since the 1980s suits for RCR have continued to remain popular with Indian men. As the renowned Indian lawyer and women’s rights activist Flavia Agnes has noted, as divorce and separation have started becoming more socially acceptable, men are increasingly filing suits for RCR as a retaliatory measure against wives seeking divorce, judicial separation and annulment of marriage.

It is against this backdrop, and in light of the recent Indian Supreme Court decisions on the right to privacy in Puttaswamy v Union of India (2017) and Navtej Singh Johar v Union of India (2018) where the latter finally overturned another regressive colonial law – the criminalisation of homosexuality, that two young students in India have sought to challenge the existing validity of restitution of conjugal rights under the HMA 1955, the Special Marriage Act 1954 and the Code of Civil Procedure 1908.

Here Nikita Samanta and I ask Ojaswa Pathak and Mayank Gupta, and their lawyer Pranjal Kishore about their experiences with the case so far.

Interviewers:

Dr. Kanika Sharma is a lecturer at the School of Law at SOAS University of London, where she also serves as the Director of the Centre for Asian Legal Studies. Her research focuses on Indian colonial legal history, and she is currently interested in the development of the idea of ‘consent’ within Hindu marital law.

Nikita Samanta is currently undertaking a PhD at the University of Warwick (UK) in Gender and Education. She is researching a collaborative programme of action to facilitate access to education in Haryana, India. Prior to this, she completed her BA in Psychology and MA in Education, Gender and International Development as a Commonwealth Scholar at University College London.

Lawyer for Interviewees:

Pranjal Kishore is a lawyer and occasional writer. He represents a diverse set of clients in civil, commercial and criminal matters in courts and tribunals across New Delhi, India.

Interviewees:

Mayank Gupta is a penultimate year student pursuing Bcom, LLB (Hons.) at Gujarat National Law University. He is a voracious reader and used to be the club-head of the university’s volleyball team.

Ojaswa Pathak is a penultimate year student pursuing BBA, LLB (Hons.) at Gujarat National Law University. He loves to read and has an interest in psychology and sociology which he hopes to use in his career someday.

Q1. Could you tell us and the readers about the public interest litigation you have brought against restitution of conjugal rights (RCR) in India?

In March 2019 we had petitioned the Hon’ble Supreme Court challenging the law of restitution of conjugal rights in India. The said law is violating the right to privacy, individual autonomy and dignity of individuals (both men and women) guaranteed under Article 21. We believe that the state has no legitimate or compelling interest in enforcing companionship and cohabitation as an aid to prevent the break-up of marriage because genuine desire between two couples can never be negotiated let alone enforced through a court of law. This law not only violates the individual and decisional autonomy of a woman to not cohabit with her husband but also is an enabler for possible domestic and sexual abuse of a woman if she complies with the RCR decree to cohabit with her husband.

Q2. What stage is the case at today and when do you think the judgment will be given?

When the matter first came up, a bench of two judges of the Court sought it fit to be listed before a bench of three judges. This was because a previous bench of two judges of the Supreme Court had upheld the validity of RCR in the case of Saroj Rani v Sudarshan Kumar Chadha (1984). The three-judge bench sought a response from the Union Government on 15th March last year. Unfortunately, the Union Government has failed to put in its response so far. When the matter was last heard – 15th January 2020, the Court sought a response from the Attorney General and gave the Union Government another 8 weeks to file a response. However, this has not yet been done. Given the situation with respect to COVID-19, the Court is not functioning at full capacity at the moment. The matter is expected to be heard again soon after normal court functioning is restored

Q3. What is the importance of the doctrine of RCR, and why do you think it has remained in the Indian legal system long after being abolished in the UK?

The Law of RCR provides that when either husband or the wife withdraws from the society of the other, the aggrieved party may apply to the Court for a direction that the other party should live with him or her. The remedy of restitution of conjugal rights traces its root back to the British Common Law and is premised on the discriminatory and archaic notion that women are the chattels of the husband. Every common law country from the United Kingdom to Canada has abolished this remedy from their legal system and India is the only legal system where it still survives. After Independence, while the Hindu Marriage Act was being formulated, various lawmakers had termed RCR as a mechanism for “legalized rape”. However, no deliberation was given to this provision because the energies in and out of the legislature were deeply concentrated in defending various other new provisions inter alia divorce. Resultantly, RCR did not go through intelligent and unbiased scrutiny and was perfunctorily copied from the English statute books. It can also be said that RCR is yet another colonial legacy of the British and is not at all unique to Indian society. Thus, it would be correct to say that the RCR law in India has survived perhaps due to legislative laxity and nothing else.

Q4. Suits for RCR are today recognised in the personal laws of all religions in India today. Why have you chosen to focus on certain personal laws alone?

Given the varied nature of different personal laws, the scope of a constitutional challenge to RCR in different personal laws would be much wider. We were advised that instead of one petition challenging RCR in different personal law systems, it would be better to file separate challenges. Further, the question of whether a person from a separate religious group can file a PIL challenging the validity of practices of another group is currently pending before a nine-judge bench of the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India that is hearing the Sabrimala Reference order. Given that both our matter and the Sabrimala reference are sub-judice, we do not want to say any further for the moment.

Q5. What inspired you to file this PIL? Did a particular case or story spark your interest?

We came to know about this archaic law in February 2018. We had read the Supreme Court’s ruling on the right to privacy and had an intuition that this law must be reviewed by the Supreme Court once again especially in view of the right to privacy being held as a fundamental right. We discussed this proposition with Advocate Pranjal Kishore and Senior Advocate Sanjay Hegde who were generous enough in helping us in fructifying this and representing us before the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India. We firmly believe that striking down of the law restitution of conjugal rights as unconstitutional would a step in the long journey towards gender justice.

Q6. In the litigation, you reproduce at length the judgment of Justice Pinhey in the historical case of Dadaji Bhikaji vs Rukhmabai (1885). As a law student, and now as a practitioner, how in your opinion can history help us understand something like RCR in the modern day?

Restitution of conjugal rights is not only a relic of our colonial past but is also based on the outdated and discriminatory premise of women being treated as chattels of their husbands. The linear nature of time has been taking us towards a future of equality and justice ergo our dynamic society has been evolving accordingly. The only place wherein laws such as restitution of conjugal rights only deserve to be is in the history books and not in the statute books.

Q7. Do you have any words of advice for fellow students who may wish to challenge historically unequal laws in their own countries?

OP: I saw a very remarkable quote in Senior Advocate Sanjay Hegde’s office. It was a story about four people named Everybody, Somebody, Anybody and Nobody. There was an important job to be done and Everybody was sure that Somebody would do it. Anybody could have done it, but Nobody did it. Somebody got angry about that because it was Everybody’s job. Everybody thought Anybody could do it, but Nobody realized that Everybody wouldn’t do it. It ended up that Everybody blamed Somebody when Nobody did what Anybody could have. We advise our fellow students to be that ‘Anybody’ who takes the initiative in the society to serve the cause of access to justice to all and challenge gender discriminatory laws without expectation of any private benefit.