In November 1818, Sarah Jeffreys of Caswell County, North Carolina, expelled something from her uterus. In a confession wrung from her after repeated denials, she testified that she “had lost something but she did not know what it was.”[1] She claimed she was alone when it happened, but that her mother, Fanny, and her friend, Betsy, later came to her aid. Together, the three women buried the remains and then went about their business. But someone, somewhere in the community thought something was amiss and notified the local Justice. And so the process of accusation, investigation, and recrimination began.[2]

What emerged as Sarah Jeffreys’s case wound its way through the legal system illuminates much about how people responded to instances of suspected abortion or infanticide in antebellum America. Jeffreys was an unmarried white woman, who already had a number of illegitimate children. The absence of a husband to provide financial support for Jeffreys and for the children probably singled her out as a particularly onerous economic burden to the community, a ‘public charge.’ That, more than anything else, possibly motivated the allegations against her and the women who aided her.

Legal approaches to pregnancy and childbirth in the early nineteenth-century U.S. were complicated and messy. Complex legal ideas became enmeshed with people’s feelings and emotions in inquests and in courtrooms. Communities knew that Infanticide and abortion may have been against ‘the law,’ but they also appreciated that law was flexible and adaptable.[3] This understanding of the legal process, though, was not necessarily seen as something requiring correction or specialized knowledge to navigate. Instead, it provided a welcome opportunity for community members to shape legal outcomes to specific situations.[4] Indeed, Jeffreys’s case was quite unusual in pre-Civil War North Carolina because she was actually prosecuted. Most women who faced accusations of infanticide, infant murder, or even abortion, never had their cases make it as far as a courtroom. That varied little whether the accused woman was white, Black, enslaved, or free.[5]Unmarried, poor women, like Jeffreys might be subject to extra scrutiny, but usually only if there was something especially suspicious. Women attracted the attention of prying neighbors, for example, if they were thought to be pregnant, gave birth unattended, and then there was no living infant. And, even if juries convicted a woman of a crime, then communities rarely punished the guilty party to the full extent, instead seeking some form of clemency.[6]

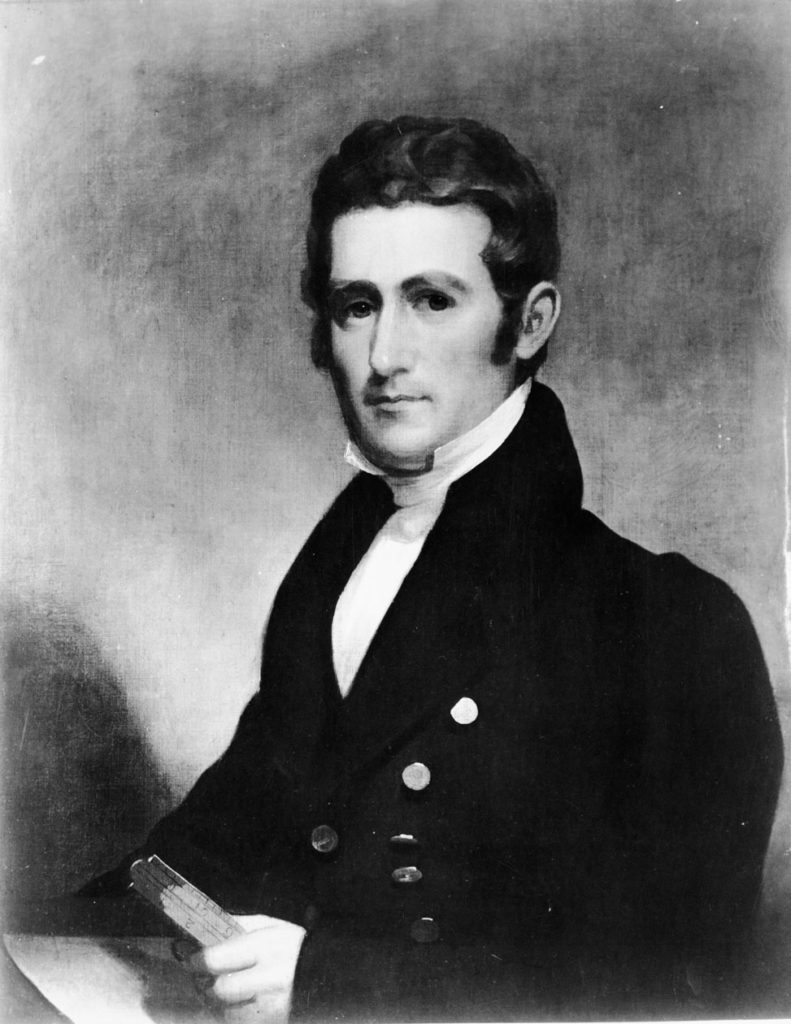

What the historical evidence can tell us about legal understandings of abortion and infanticide in the pre-Civil War United States is that local communities approached each case with an eye to every accused woman’s individual circumstances.[7] In Sarah Jeffreys’s case, once months had passed, and people’s temperaments cooled, punishing Jeffreys and her alleged accomplices for whatever had happened no longer seemed so important. Within that context, it was a problem that Jeffreys sat in jail awaiting a death sentence, but not one impossible to resolve. The Judge, Archibald Murphy; members of the jury; and other upstanding members of the community simply wrote a letter to the Governor, John Branch, asking for her release.[8]The notion that there were hard-and-fast, unyielding rules that existed in relation to crimes such as abortion, or infanticide, would have seemed alien to most people in the pre-Civil War United States. This complexity and nuance are what Justice Samuel Alito missed in his leaked draft opinion from Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health. In many states, statutes did criminalize the procurement or provision of abortion, but courts and communities did not then apply those laws in a uniform or “one-size-fits-all” way. The case of Sarah Jeffries, and of many other women like her, serves as proof of that.

[1] Information from Jennette [Jemimah] Montgomery, Initial Examination by Justices of the Peace Michael Montgomery and Archibald Samuel based upon information that Sally Jeffreys had recently been delivered of a bastard child, Caswell County, Criminal Action Papers, November 25–28 1818, North Carolina Office of Archives and History (hereafter NCOAH).

[2] State v. Sarah Jeffreys & Betsy Coombs, May Term 1819, Caswell County, Criminal Action Papers; State v. Sarah Jeffreys & Betsy Coombs, May Term 1819, Caswell County, Minute Docket Superior Court, 1807–1826; both at NCOAH.

[3] See James C. Mohr, Abortion in America: The Origins and Evolution of National Policy (New: Oxford University Press, 1978) and Leslie J. Reagan, When Abortion Was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and Law in the United States, 1867–1973 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997) for a history of changing legal approaches to abortion in the nineteenth century. For the history of changing legal approaches to infanticide and infant murder in the same period, see Felicity M. Turner, Proving Pregnancy: Gender, Law, and Medical Knowledge in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2022).

[4] As legal historians have argued, such an understanding of law and the legal process characterized the pre-Civil War legal landscape. See, for instance, Laura Edwards, Only the Clothes on Her Back: Clothing and the Hidden History of Power in the Nineteenth-Century United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022); Martha Jones, Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018); and Dylan Penningroth, The Claims of Kinfolk: African American Property and Community in the Nineteenth-Century American South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

[5] For an example of a case involving a free Black woman, see State v. Sooky Bishop, March Term 1843, Orange County, Criminal Action Papers, NCOAH. Like Sarah Jeffreys, Sooky Bishop was tried and found guilty of the crime of infanticide. But, in Bishop’s case, judgment was suspended and she never served any time in jail, either while awaiting trial or upon conviction.

[6] For relevant analyses of infanticide cases in pre-Civil War America, see Katie Hemphill, “‘Driven to the Commission of this Crime’: Women and Infanticide in Baltimore, 1835–1860,” Journal of the Early Republic 32 (2012): 437–61; Clare Lyons, Sex Among the Rabble: An Intimate History of Gender & Power in the Age of Revolution, 1730–1830 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006): 95–100; Keri Leigh Merritt, Masterless Men: Poor Whites and Slavery in the Antebellum South (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017): 128–30; and Marcela Micucci, “‘ Another Instance of That Fearful Crime’: The Criminalization of Infanticide in Antebellum New York City,” New York History 99 (2018): 68–98.

[7] See Turner, Proving Pregnancy.

[8] Request to Governor John Branch from Judge Archibald D. Murphy for Pardon of Sarah Jeffreys, March 16 1820, Governor’s Papers, 49: 356–57; Request to Governor John Branch from citizens of Caswell County for Pardon of Sarah Jeffreys, undated [@1820], Governor’s Papers, 49: 513–14; Governor John Branch, Pardon of Sarah Jeffreys, May 20 1820, Governors’ Letters Books, no. 23, vol. 2: 301; all at NCOAH.

She is the author of

She is the author of