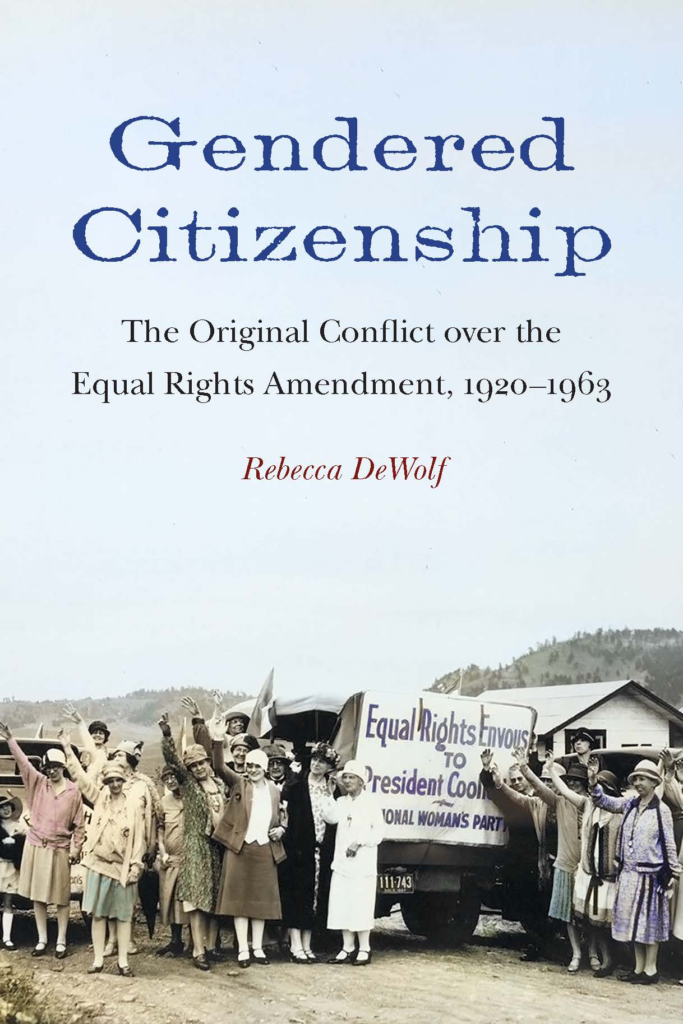

Editor’s Note: Rebecca DeWolf’s book, Gendered Citizenship: The Original Conflict over the Equal Rights Amendment, 1920-1963, was recently published by The University of Nebraska Press. Dr. DeWolf discussed her research and some of the big ideas within the book with The Docket this past December. Here is our conversation.

The Docket [TD]: Rebecca, thanks so much for taking the time to discuss your new book with us! Reading through the acknowledgements, it is clear that this project began years ago as a dissertation. Can you explain a bit for our readers how you came upon this topic, and why it was so compelling to you as a graduate student?

DeWolf:. Thank you so much for giving me this opportunity to talk about my book. I am excited to share a few of my book’s insights with you.

I became interested in the history of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) early in my PhD program. During the first year of my program (2008-2009), I was a teaching assistant for my PhD advisor’s class on the history of women in the United States. During that time, my advisor asked me to give a class lecture on the ERA. So, I began digging into the ERA’s history at that point to prepare for the lecture.

When I gave that lecture on the ERA, I opened the class up for a discussion period. To my astonishment a considerable number of students insisted that although persistent gender and sexual inequities in society continued to disadvantage women, the ERA was not a solution to those problems. That response set off a lightning bolt of curiosity for me and I began to think about several questions: Why had the recognition of persistent sex discrimination not caused a more robust push for the ERA? Why was complete constitutional sexual equality not being seen as an answer to the problems that had resulted from ongoing sex discrimination? Why did the ERA appear to be unnecessary?

Now, I gave that class lecture over a decade ago when there was still a general lack of knowledge around the ERA and nowhere near the level of support for the amendment that there is today with the recent state ratifications.[i] Even so, that response from my students made me incredibly curious about the ERA and its history. At that point I became quite obsessed with the amendment because I wanted to solve what I saw as a disconnect between the recognition of persistent sex discrimination and the reluctance to envision the ERA as a solution to that issue.

Around this time, I also had to read Susan Douglas’s Where the Girls Are for a graduate course. Douglas’s work is a brilliant exploration into the history of the media’s depiction of women and she provides an insightful discussion on how the ERA struggle represents the classic “catfight” imagery that the media has typically employed when it portrays women. This imagery depicts women as constantly fighting with each other. According to Douglas, the implicit suggestion of such imagery is that women are unfit for leadership positions because they are overly emotional and incapable of working together. Douglas explains that in the case of the ERA the media oversimplified the dynamics of the struggle as merely a fight between two groups of women: feminists (represented by Gloria Steinem) vs. antifeminists (represented by Phyllis Schlafly).[ii] My desire to get away from that catfight imagery strongly impacted the way I thought about the ERA struggle. I wanted to see if and how the ERA struggle may have been more than a fight between two groups of women.

At first, I was fascinated by all the facets of the ERA’s history, but I increasingly became more drawn to the ERA’s earliest years because the original ERA conflict calls into question central assumptions that many of us might hold about aspects of U.S. history. For instance, conservatives and liberals were not directly opposed to one another in the original conflict. As well, there were feminist supporters and feminist opponents of the amendment during the original conflict. Men also played consequential roles in the original ERA conflict as amendment backers and critics. What is more, there were prominent Democratic and Republican ERA advocates and foes during the original conflict.

In all, the history of the ERA before the 1970s complicates the typical dividing lines that have shaped other areas of U.S. history. So, I wanted to make sense of the original conflict. I wanted to see how it could fit into larger patterns and trends in U.S. history and I wanted to figure out the determining factors that were motivating people to fight for or against the ERA.

TD; One of the things that jumps out at the reader about the book is the way you are extremely precise with the language you use to explain key ideas, institutions, and moments. We have “emancipationist” activists; “protectionist” rationales; “masculine citizenship”. Did you find that the vocabulary with which scholars have discussed the ERA was too constraining? Or was this more a case of the evidence from the archives demanding a new set of ideas?

DeWolf: That’s a great question and I think it is a little bit of both.

As I suggested above, I wanted to provide a wider perspective on the ERA’s historical significance. Primarily, I wanted to see if and how the ERA struggle may have involved more than just a fight between two groups of women. As I argue in my book, when you take a wider view of the ERA’s history, so when you look at the amendment before the 1970s and when you realize that the participants in the original conflict involved more than just women who had been associated with the suffrage struggle, you start to see how the original ERA conflict changed the nature of U.S. citizenship.

Before I dive deeper into why I chose the categories of emancipationists and protectionists, I should provide a few details on the existing scholarly literature of the ERA struggle. The scholarship on the ERA has mainly looked at the amendment during the 1970s state ratification battles.[iii] While these works are important, they tend to make it seem like the ERA was a dormant or static issue before the state ratification battles. As I show in my book, the original ERA conflict was quite dynamic and consequential. There are important works that have looked at the ERA in its earliest years. These works have mostly examined the ERA in the 1920s and early 1930s. These works are essential for understanding how the ERA sheds light on the history of the women’s movement after the Nineteenth Amendment.[iv] But their focus on the ERA as mainly a fight between feminists over the priorities of women’s activism reduces the original conflict to a fight among women, about women, and only concerning women.

As I show in my book, the original ERA conflict not only took place in the 1920s and early 1930s; it lasted all the way up until the early 1960s. As well, the original conflict not only involved former suffragists; it also included an array of men and women government officials, politicians, legal authorities, intellectuals, reformers, and activists. The participants not only argued about women’s legal status, but they also contested the nature of U.S. citizenship.

Through my research I found that while feminism certainly influenced the contours of the original ERA conflict, it did not encompass the pro or anti-ERA positions in their entireties. For instance, on the pro-ERA side, you have amendment supporters who were clearly feminists, like the members of the National Woman’s Party (NWP). These ERA advocates supported the amendment to empower women. But also, on the pro-ERA side you have conservative-leaning amendment advocates, like Senator Edward Burke of Nebraska, who did not necessarily support the ERA primarily to empower women, rather they backed the amendment to attack what they believed to be superfluous government involvement in the economy.

Likewise, on the anti-ERA side, you have individuals who identified themselves as feminists, such as Mary Anderson of the Women’s Bureau. These individuals opposed the ERA and supported sex-specific laws, because, in their view, such laws improved women’s status by attending to women’s special needs. But you also have individuals on the anti-ERA side like the conservative Margaret Robinson of The Woman Patriot who denounced feminism as a threat to American society. As I discuss in my book, at its core the original ERA conflict represents a conflict between competing civic ideologies and not mainly a struggle between divergent feminist ideologies.

I use the terms “emancipationists” and “protectionists” to represent the pro and anti-ERA positions because variations of those words popped up repeatedly in the primary source materials. For example, in their arguments for the ERA, amendment supporters consistently underscored the need to fully emancipate a class of voters from their subservient legal position through the strength of a constitutional amendment that would guarantee that men and women could participate as citizens on the same terms. In contrast, ERA opponents consistently emphasized the need to protect a distinct citizenship for women to ensure what they believed to be women’s natural right to special consideration. The original ERA conflict, then, involved a profound dispute over the rights of citizenship, as emancipationists contended that American ideals affirmed the right of men and women citizens to be held to the same legal standard while protectionists insisted that true sexual equity demanded two separate collections of rights for men and women citizens.

TD: In many ways the “protectionists” lie at the crux of the narrative of your book. Can you explain for our readers who these people were and why their story was so complicated?

DeWolf: Before jumping into the protectionist outlook on citizenship and rights, I should note that I do show that there was hope for the ERA during the original ERA conflict. Although the protectionist position was dominant in the 1920s, support for the ERA increased quite dramatically in the 1930s and 1940s. While protectionists regained the dominant position in the post-World War II era, the socioeconomic and political upheavals of the Great Depression and World War II helped emancipationists create a considerable drive towards the pro-ERA position that transcended traditional political and social divides. Thus, the protectionist victory over the ERA was not a foregone conclusion to the original ERA conflict.

As I discuss in the first section of my book, the transformative possibilities of the Nineteenth Amendment produced two very different ways of looking at the rights of U.S. citizenship: emancipationism and protectionism. As noted above, emancipationists supported the ERA to ensure that a single standard of rights applied to men and women equally. Protectionists, in contrast, espoused the virtues of sex-specific rights. They opposed the ERA as a threat to what they assumed to be women’s natural right to special legal protection and consideration.

In my book, protectionism does not refer exclusively to advocates of special labor legislation for women. As I describe in my book, the protectionist habit of mind not only included liberal-minded persons who opposed the ERA and backed sex-specific labor laws for women; it also included conservative individuals who did not like labor laws. So, the protectionist position included conservatives, such as Senator Robert Taft (R-OH) and Representative James Wadsworth (R-NY), as well as liberals like Representative Emanuel Celler (D-NY) and the first woman Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins. In addition, women’s organizations that followed the maternalist reform tradition, such as the League of Women Voters (LWV), the National Consumers’ League (NCL), and the National Women’s Trade Union League (NWTUL) embraced protectionism during the original ERA conflict.

Both liberal and conservative protectionists thought that women needed special protection, they just differed in where that protection should come from. For conservative protectionists, women’s special protection should come from the male head of the household. In contrast, liberal protectionists believed that government reform efforts could also serve as effective instruments of protection for women. Even with these differences, both conservative and liberal protectionists opposed the ERA as a threat to women’s right to special protection.

A potent desire to maintain the law’s ability to treat men and women differently on account of sex after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment animated the protectionist position. Protectionists believed that while women should be respected as rights-bearing citizens, the law should not categorically combine women’s rights with men’s rights. From the protectionist mindset, “real equality” meant securing two distinct, but equally valued, sets of rights for men and women citizens.

So, a key point here is that the arguments against the ERA, especially as we see them during the original conflict, didn’t simply revolve around the idea that women shouldn’t have rights or that they should be denied their rights as full citizens. In actuality, ERA opponents insisted that they were the ones who were protecting women’s rights as citizens. Over the course of the original ERA conflict, protectionists pushed the argument against equal rights or equal legal treatment away from a pre-Nineteenth Amendment emphasis on the reasons to exclude women from certain rights of citizenship towards a post-Nineteenth Amendment emphasis on the need to develop a distinct citizenship for women that supposedly came with its own set of rights. For protectionists, women’s special rights included being exempted from military service, shielded from industrial capitalism, and kept safe in their domestic roles. In this way, protectionists modernized the rationale for sex-specific treatment during the original ERA conflict by forming a new concept of full rights-bearing U.S. citizenship that included two separate standards for men and women citizens.

TD: Anyone who opens this book will be impressed by the incredible depth of your archival research. Can you speak a bit about your archival research process? Were there any particular experiences or ‘aha!’ moments that you remember while doing your research?

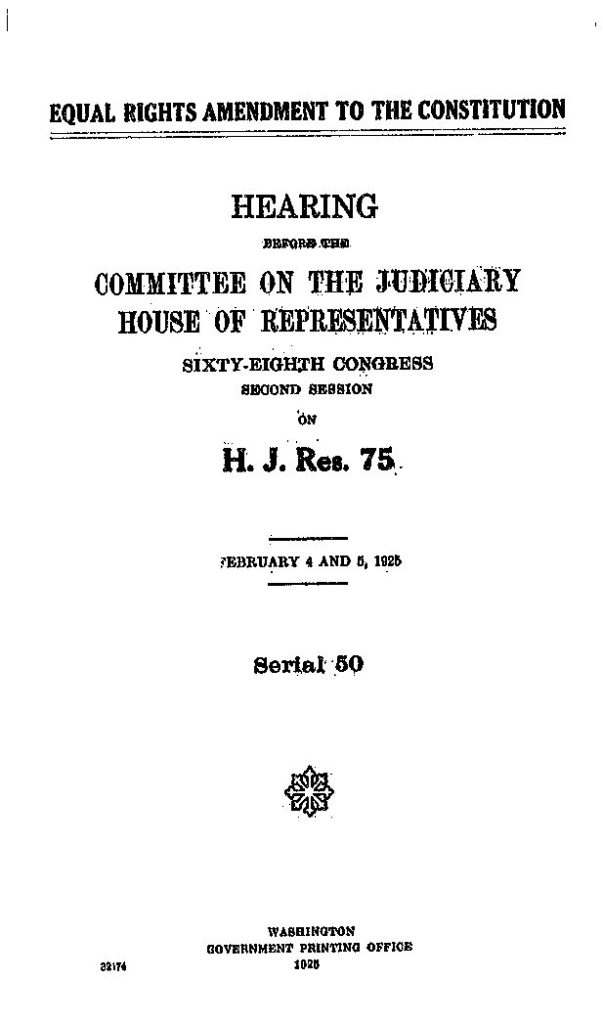

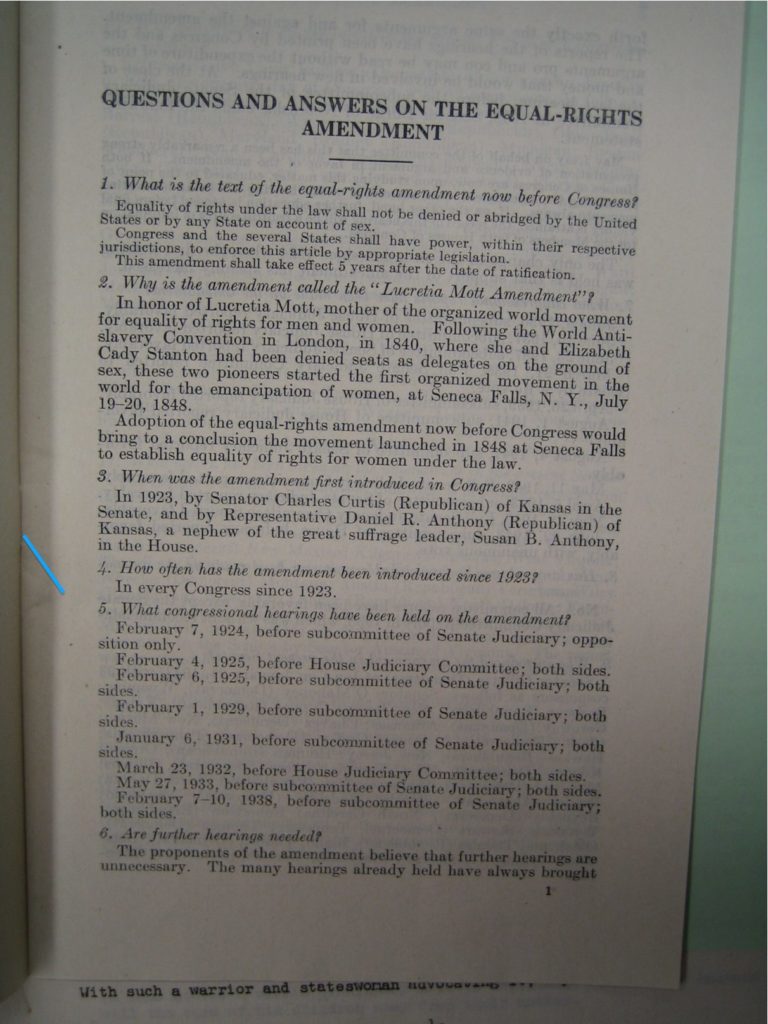

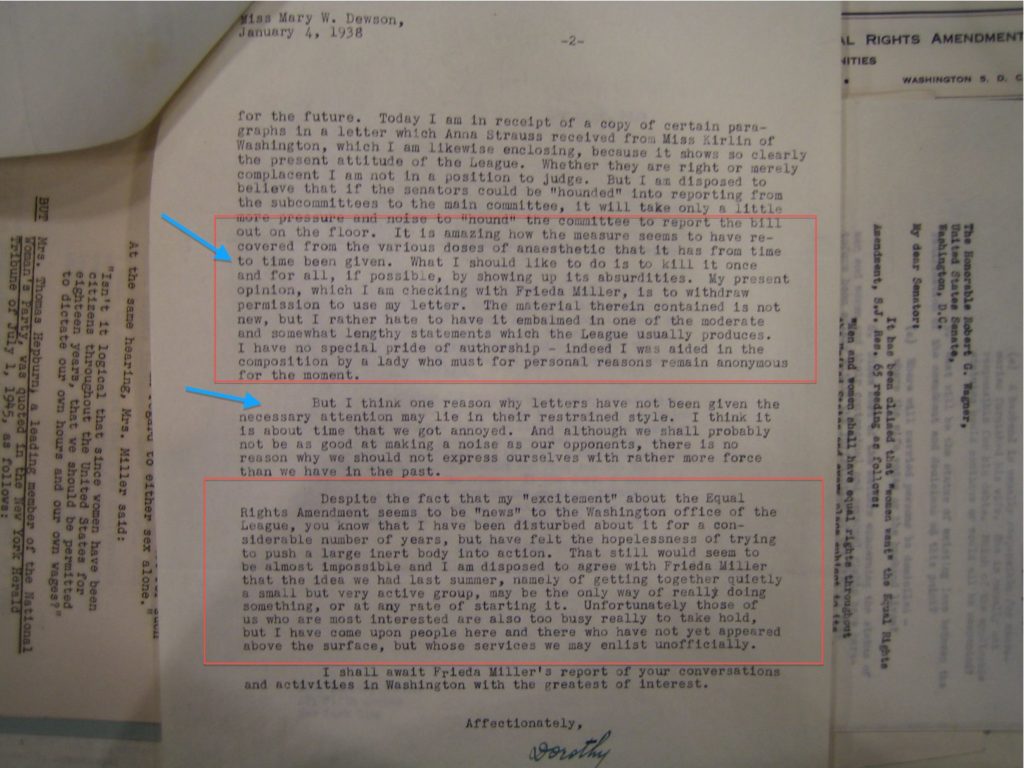

DeWolf: Since I wanted to provide a wider perspective of the participants involved in the original ERA conflict, I not only looked at the typical archival collections that other historians have used on related topics (such as the collections of major women’s organizations), but I also examined the papers of prominent legal scholars and congressmembers. As well, I explored various collections at several presidential libraries that held ERA-related materials. But the “meat” of my primary sources is the often overlooked, but extensive congressional materials on the ERA from the original conflict. Congress held numerous hearings on the ERA from the 1920s to the early 1960s. These were lengthy hearings with testimony for and against the amendment from a variety of people. Since I was most interested in understanding the core ideas embedded in the pro and anti-ERA positions, the congressional hearings were a treasure-trove of information because those hearings contained all the public arguments that ERA supporters and opponents had put forward to push the pendulum of public opinion in their favor.

Now for my “aha!” moment I need to be brutally honest about an inaccurate assumption that I held about the ERA. When I first chose the ERA struggle for my dissertation topic, I had thought that I would be writing a typical political history of the ERA’s earliest years. I was under that impression because other scholars who have given short summaries of the ERA’s early years have tended to offer up a generalization to the effect that in contrast to the political dynamics of the struggle in the 1970s early ERA supporters had been conservatives and Republicans while early ERA opponents had been liberals and Democrats. So, I thought to myself: “I will write a dissertation on what the original ERA conflict can tell us about the history of the Democratic and Republican parties.”

When I started to dig deeper into my primary source materials, I realized that I was wrong about the political undercurrents of the original ERA conflict. While going through the primary sources, I found that not only had conservatives and Republicans supported the ERA, but also various liberals and Democrats had backed the amendment in consequential ways. Likewise, I found that various conservatives and Republicans as well as liberals and Democrats had opposed the ERA in significant ways during the original conflict.

So, my big “aha!” moment came during the first few months of my preliminary research into the congressional materials as I realized that I would not be writing a typical political history because the original ERA conflict defied conventional categories of political ideology since both the pro and anti-ERA positions had included pronounced conservative and liberal variations. It was at that moment that I decided to stop putting my assumptions onto the sources and to let them speak for themselves. I made a concerted effort to focus on the language and discourse that the participants were using in their arguments for or against the amendment to understand them in their own historical context and to begin unraveling what was driving them to fight for or against the amendment. Not long after that change in approach, I began to understand that the dividing factor in the original ERA conflict was not political ideology, but rather a difference in how the participants were envisioning the role that sex should play in determining a citizen’s rights. From then on, I understood that the original ERA conflict was a dispute over the very idea of rights and that my project would be a look at how the ERA fits into the larger history of U.S. citizenship.

TD: Particularly given everything going on in the news these days, readers will likely see many connections between the story of the ERA and ongoing debates about women’s equality and citizenship in the contemporary United States. How do you think your book speaks to these debates?

DeWolf: I think that the original ERA conflict sheds important light on the reasons for the persistence of sex discrimination and the societal disadvantages that have continued to hold women back. One of my central arguments is that the original ERA conflict created the U.S.’s gendered citizenship, which has prolonged the gaps between men and women’s societal positions. As I explain in my book, ERA opponents, or protectionists, created a confidence in the supposed equity of sex-specific treatment during the original ERA conflict that still shapes society to this day.

To unpack that argument, we need to go back to one of those questions that I had asked myself after giving that class lecture on the ERA so many years ago, which was “why had the recognition of persistent sex discrimination not caused a more robust push for the ERA?” The answer that I developed through my research and writing is that protectionists were able to suppress the allure of the ERA by putting forward the idea that sex-specific rights, rather than equal rights, were fairer and more beneficial for women. According to protectionists, equal rights would be harmful for women because they would take away the sex-specific rights that women needed as mothers and potential mothers. The problem with that viewpoint is that it rationalizes the discriminatory attitude that rights should be dependent on one’s sex. In the original ERA conflict, a core notion that fueled the emancipationist outlook, or pro-ERA position, was that if sex can be a reason to give rights, then sex can be a reason to take away rights.

As I discuss in my epilogue, I still see threads of protectionism influencing society today. For instance, the emphasis in the protectionist position that there is a biologically predetermined sexual division of labor in which men are held as the primary providers and wage-earners and women are cast as the essential caregivers and homemakers in society reinforces the subordinate position of women when they do choose to pursue activities that extend beyond their conventional roles in the home. In other words, the perpetuation of the sexual division of labor embedded in protectionism ends up restricting women’s range of choices and opportunities for how to participate in life and it preserves men’s greater access to political, economic, and social power in the public realm.

TD: We always like to wrap up with a fun question! If you had to design a soundtrack for your book, give us a few tracks that you think would be a good fit.

DeWolf: What a great question! I wish I had a great answer for you. I don’t have a lot of songs to list because this is the first time that I have ever really thought about a soundtrack for my book.

Here are a few songs that should absolutely be included because they capture the emphasis on women’s empowerment embedded in the feminist side of emancipationism.

- Lesley Grove’s “You Don’t Own Me.”

- Aretha Franklin’s “Respect.”

- Aretha Franklin’s “Do Right Woman, Do Right Man.”

- Destiny’s Child’s, “Independent Woman.”

- Gloria Gaynor’s, “I Will Survive.”

- No Doubt’s “Just a Girl.”

Thank you so much for letting me share my book with you!

[i] Thanks to the lobbying work of several pro-ERA groups, the ERA has received three additional state ratifications in recent years: Nevada (2017); Illinois (2018); and Virginia (2020). These additional ratifications have presumably given the amendment the 38 states necessary for full incorporation into the Constitution, but lingering questions over the viability of the 1982 deadline have prevented the ERA from being published as the 28th amendment. See Rebecca DeWolf, Gendered Citizenship: The Original Conflict over the Equal Rights Amendment (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2021), 238-242.

[ii] Susan J. Douglas, Where the Girls Are: Growing up Female with the Mass Media (New York: Three Rivers Press, 1994), 221-244.

[iii] See Mary Frances Berry, Why ERA Failed: Politics, Women’s Rights, and the Amending Process of the Constitution (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986); Jane Mansbridge, Why We Lost ERA (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986). See also Janet Boles, The Politics of the Equal Rights Amendment: Conflict and Decision Process (New York: Longman, Inc., 1979); Gilbert Steiner, Constitutional Inequality: The Political Fortunes of the Equal Rights Amendment (Brookings Institution Press, 1985); and Joan Hoff-Wilson ed., Rights of Passage: the Past and Future of the ERA (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986).

[iv] See William O’Neill, Everyone Was Brave: A History of Feminism in America (Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1969); J. Stanley Lemons, The Woman Citizen: Social Feminism in the 1920s (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1981); Susan Becker, The Origins of the Equal Rights Amendment: American Feminism Between the Wars (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1981); Felice D. Gordon, After Wining: The Legacy of the New Jersey Suffragists, 1920-1947 (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1986); Christine Lunardini, From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party, 1910-1928 (New York: New York University Press, 1986).

Dr. Rebecca DeWolf

Dr. Rebecca DeWolf