For observers of academic legal discourse, the invocation of “natural law” in recent scholarship ought to seem somewhat unremarkable. Since the publication of Adrian Vermeuele’s 2020 essay in The Atlantic, “Beyond Originalism,” in fact, natural law—and especially its relevance to modern constitutional interpretation—has become a frequent subject of debate in the legal academy. From Vermeule’s own Common Good Constitutionalism (2022) to the voluminous scholarship of Joel Alicea, Jud Campbell, Jeffrey Pojanowski, Lee Strang, and Kevin Walsh, there is no shortage of new books and articles that engage questions related to natural law and the American constitutional tradition. Moreover, several important historical treatments of natural law have appeared in recent years, including Stuart Banner’s The Decline of Natural Law (2021) and Kody Cooper and Justin Dyer’s The Classical and Christian Origins of American Politics (2022). Since 2023, I myself have published a series of articles on, among other topics, natural law’s relationship to civil rights and legal education, devoting particular attention to often-overlooked religious figures who helped to shape twentieth-century debates about American law and politics. And I have offered constructive criticism of recent scholarship that has not, in my view, sufficiently captured natural law’s importance to the legal history of the twentieth-century United States.

As I observe in a forthcoming article in the Georgetown Journal of Law and Public Policy, the legal profession has largely purged from its “constitutional memory” the frequency with which debates about natural law and the Constitution have recurred in the United States. Indeed, even today’s most thoughtful proponents of natural law jurisprudence appear to have impliedly accepted the narrative that natural law was excised from the United States during most of the twentieth century such that the frequency with which natural law has recently been invoked seems representative of a new “natural law moment in constitutional theory.”

Regardless of whether one is a proponent or opponent of today’s “natural law moment,” it remains true that invocations of natural law have been a consistent feature of American legal history. As Stuart Banner, Andrew Forsyth, and R. H. Helmholz, among others, have demonstrated, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century lawyers and jurists in the United States were widely informed by the natural law tradition of their English predecessors—who were themselves drawing on and reformulating the insights of continental scholastic philosophers. As one participant in today’s “natural law moment” remarks in a forthcoming article, “The [natural law] tradition … was expanded upon by the likes of Cicero, Augustine, and Aquinas. Thinkers like Suarez, Grotius, and Locke carried the tradition into the modern period. And learning from them, the Founders carried the tradition across the Atlantic to the New World.” Unsurprisingly, Johnathan Gienapp’s much-discussed Against Constitutional Originalism (2024) thus substantiates its most poignant critique of originalism on the premise that today’s originalist jurists and legal scholars largely misunderstand how the Constitution’s eighteenth-century drafters and ratifiers understood the nature of law (and, relatedly, of written constitutionalism).

Historians ought to be wary of making predictive judgments, but it seems likely that originalists may respond to Gienapp’s critique by turning to scholarship on the founding that emphasizes natural law’s centrality to the “intellectual air” in which the Constitution’s drafters and ratifiers were situated. Should they do so, the originalist movement that was catapulted into the national mainstream in the 1980s and 1990s by the Federalist Society—a movement that was philosophically positivist and, in many respects, seeks to remain so today—may soon be reshaped in ways that the movement’s earliest leaders might not have anticipated. As I have noted elsewhere, for example, future originalists may conclude with increased frequency that “ascertaining the original meaning of a legal text requires an inquiry into how the drafters of that text might have themselves proceeded from natural-law priors in their drafting.” But notwithstanding the eventual accuracy of this predictive judgment, an important task remains for American legal historians—namely, to explain what became of natural law after it was seemingly excised from domestic legal discourse during the last century.

According to Stuart Banner and most other scholars of nineteenth- and twentieth-century American legal history, whatever influence natural law had on the legal profession quickly diminished between the end of the Civil War and the advent of legal realism in the 1920s and 1930s. To be sure, Edward Purcell demonstrated decades ago how natural law-inflected modes of legal and philosophical reasoning endured during the 1930s and 1940s, but an important question nevertheless remains about what happened in the American legal profession after the so-called “decline of natural law.” To offer one (far from comprehensive) response to this question, I turn in my new Law and History Review article to the Natural Law Institute (NLI), an academic initiative of the University of Notre Dame that effectively promoted natural law jurisprudence in the legal academy and the public square during the mid-twentieth century.

After natural law’s “decline,” a wide array of American lawyers and scholars developed programs to restore natural law’s once-dominant position in mainstream legal discourse. As John Breen and Lee Strang argued in a 2011 article in the American Journal of Legal History, these lawyers and scholars were frequently affiliated with Catholic educational institutions in the United States—in part because of the Catholic Church’s longstanding association with scholastic philosophy. As the most prominent Catholic university in the mid-twentieth-century United States, it is therefore of little surprise that Notre Dame established the NLI in 1947.

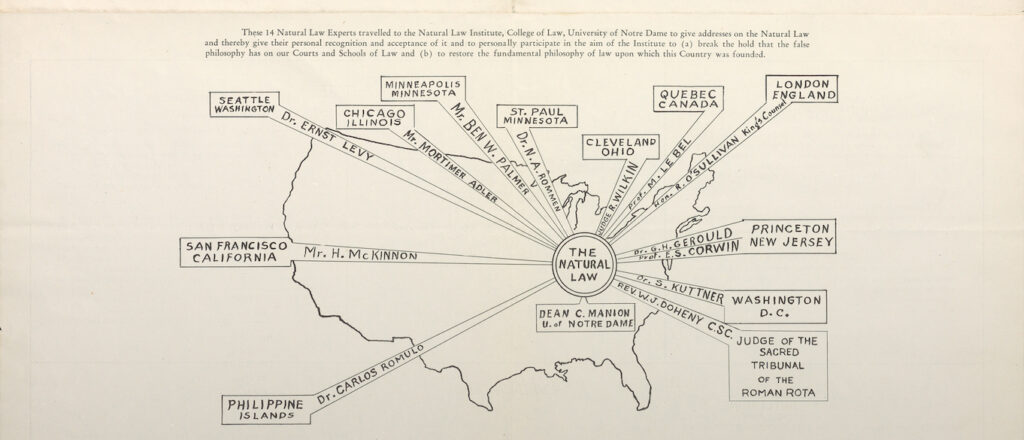

To demonstrate the NLI’s significance for our understanding of twentieth-century constitutionalism in the United States, my new Law and History Review article uncovers the aspirations that natural lawyers had for the NLI, the ideas about the American constitutional tradition that they developed, and the day-to-day efforts that they undertook to expand their mid-century natural law movement. Following Amanda Hollis-Brusky’s Ideas with Consequences (2015), the article reveals how the NLI built a “political epistemic network” of natural lawyers that was not as marginal at mid-century as scholars have traditionally assumed. Indeed, understanding the history of the NLI reveals that, during this creedal period in American legal history, influential ideas about natural law’s relationship to the Constitution were developed; institutions were built to add theoretical complexity to those ideas; and interpersonal networks were forged to bring those ideas to ever-wider audiences of lawyers, jurists, and lay Americans. In my view, these findings challenge the conventional wisdom about natural law’s “decline” because they illustrate that natural law was a pervasive theme in the last century’s constitutional discourse.

In concluding, it bears noting that the NLI was distinctive (as compared to other twentieth-century natural law initiatives) in the sense that it was identifiably conservative in its political-philosophical orientation. This is largely attributable to the NLI’s founder, Clarence E. Manion—a former dean of the Notre Dame Law School who would later become a prominent conservative radio broadcaster. From issues of sexual morality to economic regulation, most jurisprudential positions that the NLI attempted to popularize were “conservative” in the way that scholars understand this term today. For example, I note in my article that one undergraduate student at Notre Dame looked to the NLI to explain the “basic[] immoral[lity]” of New Deal-era labor regulations. Likewise, Clarence Manion characteristically invited conservative “spokesman” George Sokolsky to offer a keynote address at the NLI’s 1950 convening in which Sokolsky critiqued, among other deleterious trends, the decline of the so-called American “family system.”

As Amanda Hollis-Brusky, Steven Teles, Ann Southworth, and other political scientists have long-argued, American conservatives have been skilled institution-builders—that is, architects of well-funded and well-connected institutions that enable “conservative” ideas to reach judges and policymakers. Hollis-Brusky, for instance, has therefore devoted much of her incisive scholarship to understanding the history of the Federalist Society, the institution widely credited with the originalist re-shaping the federal judiciary during the first Trump Administration. As I demonstrate in my new article, however, the Federalist Society was far from the first (or most influential) “conservative” law and public policy institution established in the United States during the twentieth century. Indeed, the NLI not only enabled (in)famous conservative pundits like Clarence Manion to enter the American political mainstream, but it also helped to supply young law students—such as William Bentley Ball, a 1948 Notre Dame graduate who argued Wisconsin v. Yoder and several other high-profile First Amendment cases before the Supreme Court—with intellectual capital on which they later relied in practice.

The NLI’s conservative political-philosophical orientation is but one feature of natural law’s twentieth-century American history. In fact, natural lawyers like William J. Kenealy—who, as my article notes, publicly praised the NLI—was himself a prominent leader of the Civil Rights Movement. Moreover, many (especially Catholic) natural lawyers praised New Deal economic policies because they seemed well-poised to advance the Catholic Church’s vision of a more just economy. As such, if future historians turn to the twentieth century to understand what became of natural law after its so-called “decline,” the temptation to reflexively associate natural law with American conservatism merely because many leaders of today’s “natural law moment” are pejoratively labeled as “conservative” ought to be resisted. If scholars instead seek to recover the nuances in twentieth-century debates about American law and politics by remaining attentive to natural law’s place therein, I suspect that our understanding of conservative constitutionalism will be enriched, and that we may also find that natural lawyers’ “constitutional imaginations” have often resisted categorization along neat conservative/liberal ideological lines.