This short essay is about the problem of what to do with the accidental discovery of a primary source, a research gem, that is beyond the scope of one’s current projects. It is also a reflection about the legal history community and the subjective necessity for writing.

Part I. The Journey to Discovery

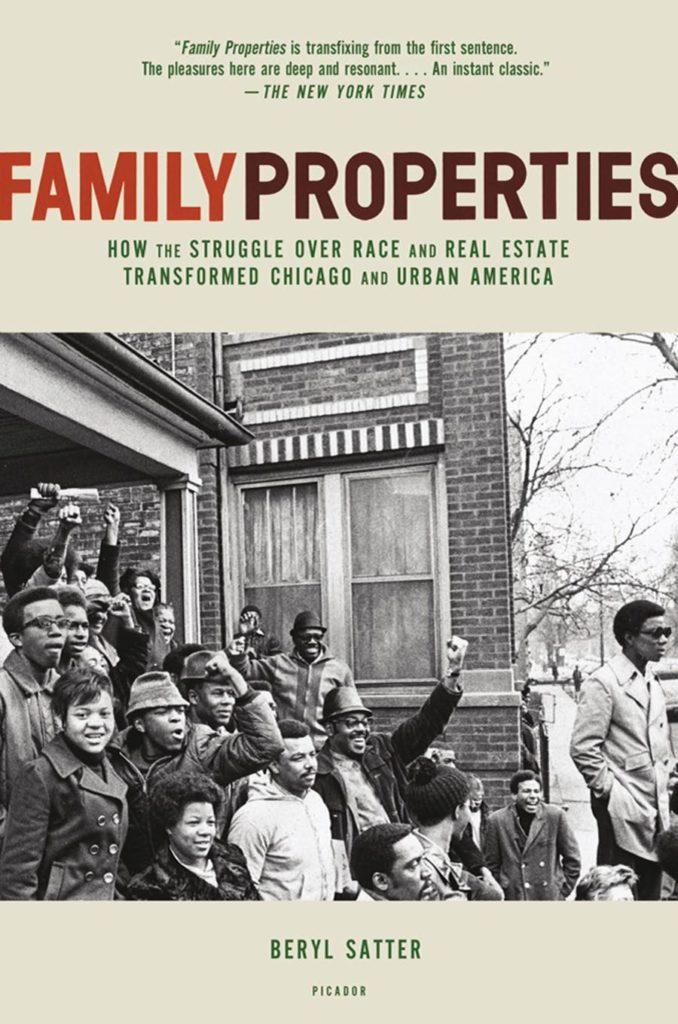

Thanks to an after-dinner conversation with Daniel Sharfstein and Andrew Wender Cohen at the recent annual meeting of the American Society for Legal History in Chicago, I ordered a copy of Beryl Satter’s Family Properties. It’s a searing account of real estate and racial exploitation in mid-twentieth-century Chicago. Satter tells the story of her father’s legal advocacy for his African American clients and his simultaneous struggles as a landlord that led to his early death. Beryl was only six when her father passed away and barely knew him. The book spoke to me because I had lost a father as a child and only later learned about his scholarship and professional identity. In addition, I did my graduate work at the University of Chicago and had lived in Hyde Park—one of the peripheral sites of Satter’s study—during the early 1990s. I have haunting memories of the university police presentation during the graduate student orientation. The officer sternly warned us not wander into the surrounding neighborhoods on the South Side.

I initially hoped that Family Properties would help Máximo Langer and me puzzle through an empirical research finding about race and juvenile incarcerations rates in the 1950s for the book that we are writing about the arc of American juvenile justice. We had already written a section about a key meeting in 1959 of reformers at the University of Chicago but had not contextualized the neighborhood where they met. Satter’s book helped us to understand more precisely how an urban renewal program had transformed Hyde Park.

While searching for additional primary sources, I found a fascinating 1959 journal article, “Residential Integration: the Case of Hyde Park in Chicago,” by Sol Tax. At the time, he chaired the university’s Anthropology Department and served as President of the American Anthropological Association. Tax explained the role that faculty members and Hyde Park residents such as himself had played in the planning process that had prevented the neighborhood “from becoming a slum” and instead to “develop a stable, interracial community of high standards.” And, as he noted, “We needed to keep our skirts exceedingly clean on the race issue. Yet, we were forced, in fact, to discriminate heavily, in the matter of housing, against the Negroes, the most deprived group in the city.”

After learning more about Tax, his field of action anthropology, and his role in bringing representatives from Indigenous nations to Hyde Park in 1961 to unify around the idea of tribal sovereignty, I knew enough to write a short paragraph for our long book.

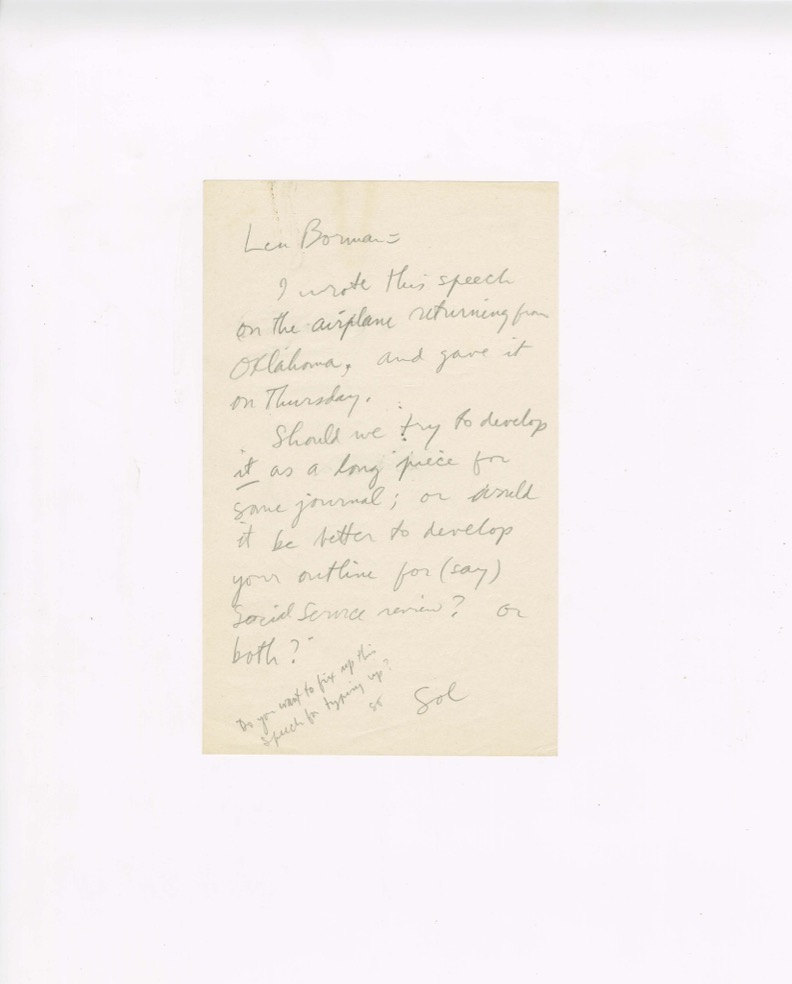

Before moving on, I wondered whether Tax had written about juvenile delinquency. The Hanna Holborn Grey Special Collections Research Center at the University of Chicago holds Sol Tax’s papers, all 351 boxes of them. A search revealed only one item: “An Anthropologist Looks at Juvenile Delinquency, [1957], typescript, notes.” Several days later I had secured a scan of the file that contained a hand-written note, an outline, and a typescript of the speech.

II. The Power of a Primary Source

In a hand-written note to his graduate assistant Leonard D. Borman, Tax stated, “I wrote this speech on the airplane returning from Oklahoma, and gave it on Thursday.” Thanks to newspapers.com, I learned that Tax had been in Tulsa at the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) annual meetings. On Wednesday, October 30, before departing he had participated in a panel discussion held at the Oklahoma Military Academy—”the West Point of the Southwest”—on the past, present, and future of U.S. Indian Policy. The famous psychiatrist Karl Menninger and NCAI President Joe Garry were his fellow panelists, and Oklahoma Supreme Court Justice N.B. Johnson moderated the discussion. Tax and his fellow panelists may even had attended a morning breakfast on youth programs, which the NCAI and the Boy Scouts of America had co-sponsored.

I tried to imagine what Tax’s flight from Oklahoma to Chicago was like near the end of the first era of mass air travel and before jet passenger service began.[1] The frontpage of the Tulsa Tribune included a description of plane crash in Arizona that had killed sixteen airmen. Was Tax worried about flying? Did writing a speech help distract him?

I still don’t know who invited him to discuss juvenile delinquency, or where he delivered the speech. I confirmed that he was back in Chicago on Thursday. Rabbi Ralph Simon and Tax participated in a dessert luncheon where they discussed “the problems of religious identity, individuality, and community responsibilities.” The public affairs committees of eleven South Side Sisterhoods sponsored the event, which was held at Congregation Rodfai Zedek in Hyde Park. Did Tax depart after dessert to discuss delinquency? Perhaps back to campus.

There are a few clues in Tax’s note to Borman. Tax asked “Should we try to develop it as a long piece for some journal; or would it be better to develop your outline for (say) Social Service Review? Or both?” He then added, “Do you want to fix up this speech by typing it up?” The original speech from the flight no longer exist; the file contains only the “fixed up” typescript. Let’s call it, the Tax-Borman text. Perhaps Margaret Rosenheim, who taught at the School of Social Service Administration and was a national expert on juvenile justice, had asked Tax and/or Borman to provide an anthropologist’s perspective on the topic. She later organized the 1959 conference at the university about justice for the child, which Máximo and I write about in our book. She also introduced me to the field of juvenile justice and helped supervise my dissertation during the 1990s.

I read the Tax-Borman text as a window into the intellectual world of 1957. It helps me to understand who social scientists such as Tax and Borman would have read to learn more about the pressing issue of juvenile delinquency. The text helped to confirm an argument that Máximo and I are making about the significance of the 1950s for the history of juvenile justice and due process. The speech, which was written before the Warren Court’s Due Process Revolution of the 1960s, concluded: “”A juvenile court system whose constitutionality has been questioned by many as denying due process of law to youth brought before the court may not be the best means for helping our youth become self-sufficient adults.”

The text is also a jarring reminder about that time period. “Equally honest, virtuous, people of good will,” Tax-Borman declared, “can differ on issues of

freedom vs. order or security

management vs. labor

states rights vs. civil rights

integration vs. segregation

federal control vs. private control

birth control vs. no birth control

breast feeding vs. bottle feeding

pacifism vs. militarism

etc.”

I keep returning to that list, and that damned etc. At one level, it’s a Cold War artifact, a reflection of the times. Perhaps because of the present uncertainty about constitutional rights I can’t stop thinking about how the list glides from federal control vs. private control to birth control vs. no birth control, followed by breast feeding vs. bottle feeding. The list is a stark reminder about how intimate relations, whether sexual intercourse or feeding a newborn, are intertwined with constitutional culture and the power of experts.

The text is also an extended argument for thinking historically about the problem of juvenile delinquency, or as the text asks: “What does our long view of history tell us about youth problems?” The answer begins with their living present:

“In 1956 Lindner said it was mutiny, that the gang of Pachucos, ‘with their identifying tatoo [sic], their code of violence and their uniform dress, seem to be spreading everywhere and welding the hitherto warring gangs into a solid front associated for common criminal purposes.’ He said that ‘something like it bids fair to become the mold from which the mutinous pattern of the young is to be cast in the future.’“

Tax/Borman juxtapose this assessment by Robert Lindner, the author of Rebel Without a Cause (1944) and Must You Conform? (1956), with a similar assessment of German and Irish children in Charles Loring Brace’s The Dangerous Classes of New York (1872). The juxtaposition shows how an earlier generation also condemned young people as different and inherently dangerous. This view from an anthropologist about the history of juvenile delinquency resonated with me because I had read excepts—perhaps the exact except—from Brace’s book as part of the collection of primary sources that Margaret Rosenheim used to teach generations of social workers about enduring issues in poor relief. Perhaps Borman had also taken Rosenheim’s course. Perhaps he had prepared his initial outline for her.

I was almost ready to move on from this text. But what about those Pachucos? My own scholarship on juvenile justice has too often overlooked Latinx youth. I emailed Bill Bush and Doris Morgan Rueda, both of whom have written about Latinx youth. They helped me to understand why these youth would inscribe Catholic imagery—often a small cross—between their thumbs and pointer fingers. And, as Doris wrote,

“It struck me after I sent the email, how youth might be using those tattoos as a way to protest the lack of Catholic services provided to them at juvenile detention centers and/or affirm their identity within spaces that may not recognize Catholicism. In both Texas and Arizona, it became apparent that Catholic services or Catholic priests were not readily available to incarcerated youth, despite Latinx and Catholic youth sometimes being the majority of the youth in places like Fort Grant. I could possibly see situations in which youth are utilizing found materials (most likely pens and pins or needles) to create these tattoos. Just a last minute thought!“

Wow.

III. The Subjective Necessity for Writing

A conversation with friends that began in Chicago in November about the city’s troubling history took me on a journey back to Hyde Park that ultimately led to a forgotten speech. To make sense of this source, I felt compelled to write about it. Maybe I had to write about this source because I had assumed that it was beyond the scope of my current writing projects. But was it? Addie Rolnick and I are writing a casebook, titled Enduring Issues in Juvenile Justice, that seeks to introduce law students to the field of juvenile justice via an introductory chapter of primary sources. Perhaps “An Anthropologist Looks at Juvenile Delinquency” should be included. I wonder what Margaret Rosenheim would say.

[1] https://airandspace.si.edu/explore/stories/evolution-commercial-flying-experience#1941, accessed on December 9, 2022.