How should the courts interpret “due process?”

The Fifth Amendment indicates to the federal government that no one shall be “deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law.” The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, uses the same words, often called the Due Process Clause, to describe an obligation of the states. That amendment was designed to protect the rights of former slaves in the South against state laws to restrict their freedom.

But the actual meaning of those words has been the subject of discussion and debate for more than two centuries.[1]

Judges and courts have interpreted and applied the clause in particular cases, depending on the circumstances. Occasionally, judges have written in other venues about what due process means. These infrequent pronouncements are meant to set forth general principles, unconstrained by the need for a specific application. But they may also be intended to affect the way other courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court, looks at things.

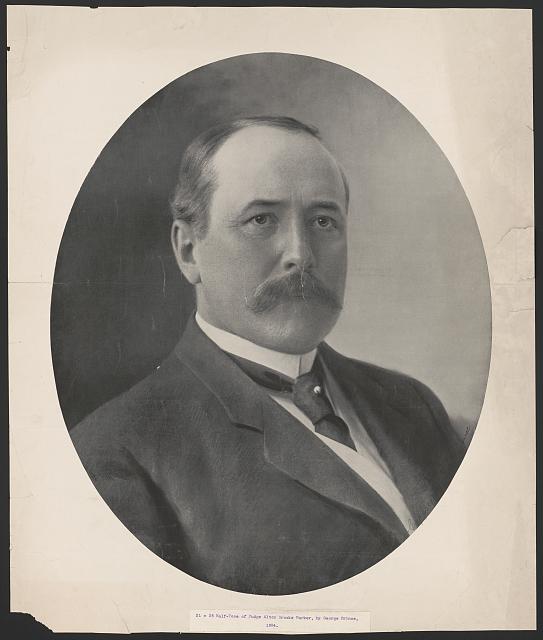

Alton B. Parker, Chief Judge of the New York State Court of Appeals, 1897-1904, publicly explored the due process clause in 1903.

Parker (1856-1924) is usually ignored by historians today, but in his time he was one of the nation’s leading judicial statesmen. In those days, it was states’ courts where most constitutional issues were thrashed out and settled; appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court were much less common than today. The New York Court of Appeals was arguably the most important state court in the nation. Other state courts heeded what the court – and in particular its Chief Judge — said.[2]

Moreover, by 1903, Parker, a proven vote-getter in New York, a state whose electoral votes were critical at that time to winning the presidency, was a frontrunner in the quest for the Democratic party presidential nomination in 1904. That meant his opinions were all the more important.

Parker Explains Due Process to the Public

Parker journeyed to Tallulah Falls, Georgia, in July 1903 to address the state bar association on the topic of “Due Process of Law.”[3] Parker was testing the waters and building support for his presidential candidacy in the south. His masterful speech was also intended to influence other courts, including hopefully the Supreme Court, and appeal to the general public. It was replete with references to court decisions but also explained things in terms the public could understand.

The judge made three key points.

*”Due Process of Law” is synonymous with “the law of the land.”That concept, said the judge, traces to the English Magna Carta. That document restrained the king of England; the “due process” clause restrains the federal and state governments.

*The due process clause in the 14th Amendment originated in the need to protect the rights of newly-liberated slaves in the south, Parker insisted. He denied the interpretation that underlay several recent court decisions, that the amendment was actually designed to protect businesses from government regulation. If that had been the justification, he explained, voters would not have ratified the amendment when it was adopted in 1868. The years around 1900, often called the Progressive Era, saw the passage of many state laws to reign in and regulate business. Courts too often were invoking the 14th Amendment “to challenge the action of State Government” in exercising appropriate regulatory oversight. That needed to be curtailed, said the judge.

*The Supreme Court has confirmed the states’ broad regulatory powers.Parker sounded a note that had characterized several of his own decisions in New York: the states have broad “police power” to regulate in the public interest.

Challenges to those powers, particularly power to tax, have usually been turned back by the high court. “[T]he tendency of later years to assume that the judicial department of the government should review and correct the errors of the legislative and executive authorities has received little support from the United States Supreme Court” said Parker. The Supreme Court has applied the restriction “far more conservatively” than some of the state courts. That was a good thing, and it should continue.

In fact, the judge was being optimistic or perhaps engaging in a bit of wishful thinking. The court had been mostly light-handed in applying the due process clause to kill regulatory laws. But as its membership changed, it had sometimes been more amenable to arguments from business interests to use the clause to strike down the laws. For instance, in 1897, in Allegeyer v. Louisiana, the court had struck down a state law regulating insurance companies, citing the 14th Amendment’s protection of individual liberties.[4] In his address, Parker had chosen to emphasize evidence that proved his point and to downplay contradictory evidence.

The Georgia attorneys liked the notion of states’ rights and the implied pushback on federal interference, in this case the Supreme Court striking down state laws. The Association hosted a banquet in Parker’s honor. There were cheers of “Our Next President!” The speech was widely covered in the newspapers.[5]

The judge had scored a hit.

Parker Explains Due Process to the Judicial Community

Parker quickly followed his Georgia speech with a three-part article in the legal journal American Lawyer in July-September 1903.[6] Writing in a journal widely read by attorneys and judges (hopefully including Supreme Court justices) was intended to convey his views to the judicial community.

The Supreme Court should show restraint in applying the 14th amendment to state regulatory laws, said Parker. After a scholarly review of the history due process clause in both the 5th and 14th amendments, Parker cited many cases where the Court had done just that – decisions where state laws “have been sustained as a valid exercise of the police power.” The list of cases was long, varied, and impressive, showing the judge’s grasp of judicial history.

Parker expressed the hope that the court would continue in that vein.

In support of his position, he concluded the last of his three in the journal articles by quoting the high court’s own pronouncement in Holden v. Hardy (1898).In that decision, the court had sustained a Utah law regulating working hours. “[W]hile the cardinal principles of justice are immutable, the methods by which justice is administered are subject to constant fluctuation…. [Because] the Constitution of the United States is necessarily and to a large extent inflexible and exceedingly difficult of amendment, [it] should not be so construed as to deprive the States of the power to amend their laws to make them conform to the wishes of the citizens as they may deem best for the public welfare without bringing them into conflict with the supreme law of the land.”

That made Parker’s point very nicely, using the Supreme Court’s own words.

Parker Applies His Interpretation

Parker had already applied his interpretation in a number of New York decisions. As he spoke and wrote, he had one eye on another case making its way through the court system in his state. People v Lochner focused on the constitutionality of an 1895 state law regulating bakers’ working hours and conditions. That seemed relatively trivial in the grand scheme of things. But if the law stood, that would be a green light to other, more expansive state regulatory legislation. If it fell, that would be a red light, or at least an orange one, for legislators. Parker anticipated the case would reach his court on appeal, which it did in October 1903. By then, it had garnered a good deal of public attention and was regarded as something of a test case.

The Chief Judge assigned himself to write the court’s opinion. Parker had three motives. One, to decide a high-visibility case (and hopefully set a model for) broad regulatory authority in spite of the 14th Amendment. Two, to influence other courts (hopefully including the Supreme Court) to endorse his ruling and views. Three, to boost his quest for the presidency – he would appear as a judicial statesman that others respected and also a champion of regulating business, a theme of growing popularity in the emerging progressive era.

Parker issued the court’s decision on January 12, 1904.[7] It was a well-argued opinion with a strong endorsement of the law, of states’ regulatory powers, and of a limited interpretation of the 14th Amendment. Due process should not deter state regulations, said Parker. “The courts are frequently confronted with the temptation to substitute their judgment for that of the legislature,” Parker wrote, but whether legislation is wise “is not for us to consider.” When a judgment is needed, “the court is inclined to so construe the statute as to validate it.” The court divided – it was a 4-3 decision, with the minority citing 14th Amendment constraints – but Parker’s opinion elevated his stature as a judicial statesman and a modest progressive reformer.

As it turned out, the Democrats were short on strong presidential candidates that year. Parker had shown his popularity with voters in New York, whose electoral vote would be critical to victory in November. He was a recognized judicial statesman. His friends (particularly former New York governor and senator David B. Hill) had quietly built support for his nomination. His Lochner decision burnished his credentials as a progressive reformer and put him over the top. In July 1904, he easily secured the presidential nomination.

To that point, Parker’s judicial and political strategies had worked well.

Parker’s Political Appeal Is Limited

Parker resigned from the court in August and his campaign began.[8]But he decided not to go around the country giving speeches to appeal to voters, instead hosting groups of the faithful at his estate in Esopus New York and making speeches there, which the newspapers sometimes, but not always, reported. Parker’s campaign was weakly organized, under-funded and uncoordinated. He had no real campaign issues to use against his opponent, incumbent president Theodore Roosevelt, who had compiled an energetic record of reform and international accomplishments, including starting the Panama Canal.

Surprisingly, Parker chose not to emphasize his Lochner opinion or his 14th Amendment views (though supporters circulated his Lochner opinion as a campaign document.) Instead, the candidate emphasized the value of common law (also known as “judge made law”) in interpreting and stretching the constitution and existing statutes to cover changing conditions. That seemed a bit at odds with his previous support for state regulation.

At the end of the campaign he accused TR of accepting campaign funds from big business. The president denied it and the judge could offer no proof. The accusation fell flat.

On election day in November, Alton Parker sustained one of the greatest defeats in American history, carrying only the southern states, which had been reliably Democratic since the Civil War. It is probable that no Democrat could have beaten Roosevelt in 1904.

But it was clear that Parker’s views on due process and the 14th Amendment had been an insignificant factor.

Parker’s Interpretation Fails at the Supreme Court

In the meantime, Parker’s Lochner decision had been appealed to the Supreme Court. Five months after the election, on April 16, 1905, the Supreme Court rendered its decision in Lochner v. New York.[9] By then, Alton Parker was no longer Chief Judge of New York and was a defeated presidential candidate rather than a leading jurist who merited deference.

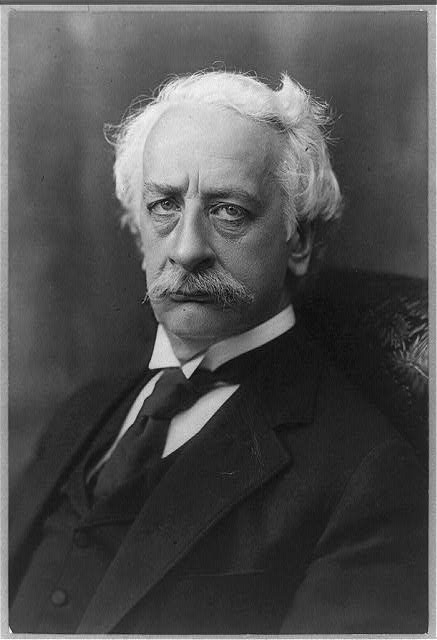

The court’s opinion was written by Associate Justice Rufus Peckham, who knew Parker from their days serving on the appellate divisions of the New York state supreme court. Peckham had gone on to Court of Appeals and then the Supreme Court in 1896; Parker was elected Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals in 1897. They also parted company on judicial philosophy. Peckham pushed the 14th Amendment as a bulwark against state regulation. He had written the majority opinion in Allegeyer v. Louisiana and had dissented in Holden v. Hardy, both mentioned above. In the ensuing years, Peckman’s influence on the court had grown.

Justice Rufus W. Peckham (c. 1898). Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

It was clear in Peckham’s spirited Lochner v. New York opinion that the Court had not heeded Parker’s advice to go easy on state regulatory law. In fact, close to the opposite.

The state had no business regulating bakers’ hours and working conditions said the court. It violated both the employer’s and the employee’s freedom of contract without due process. “There is no reasonable ground for interfering with the liberty of free contract by determining the hours of labor in the occupation of a baker,” said the court. New York’s law was unconstitutional. Moreover, the court’s expansive language laid out principles for broadly applying the due process clause as a bulwark against reform legislation.

The court’s Lochner decision had wide influence and was cited again and again over the next couple of decades in striking down state regulatory laws and discouraging the passage of new ones.

Parker’s Continuing Influence

Parker never ran for political office again. He blamed his 1904 defeat on division in his own party, “demagogic appeals” by Roosevelt and the corrupt corporate money that had fueled the Republican campaign.

Parker did not publicly comment on the Supreme Court’s New York v. Lochner decision at the time. But in 1910, his nemesis TR was seeking another term as president and as part of his campaign, he castigated the courts for overturning regulatory laws. Roosevelt had been president when Lochner v. New York was handed down in 1905, but, like Parker, he had made no public statement about it then. In 1910, though, he cited it as an example of the courts misusing the 14th Amendment to kill progressive reform.

Regarding Roosevelt as a threat to judicial independence if he should be elected, Parker came to the Supreme Court’s defense. Both the New York Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court had issued divided opinions on the case, a sign that “the case was a close one, about which minds much differ.” All judges and courts merited respect even if you did not agree with them said the ex Chief Judge.Presidents (and presidential candidates) should not presume to challenge the courts or encroach on their authority.[10] (In the event, TR failed to garner the Republican nomination in 1912, ran as an independent on the new Progressive Party, and lost the election to Democrat Woodrow Wilson.)

Parker wrote several law review articles after his campaign, but, something of a mystery, he did not continue emphasizing his interpretation of due process.

Instead, he explained that state legislatures, groping for remedies to complex social and economic problems or driven by the press or popular clamor, were passing too many laws. Many were poorly drawn and flawed by the time they reached the statute books. When they were challenged in court, judges had the burden of interpreting and applying them and, sometimes, striking them down as unconstitutional. That, in turn, subjected the courts to unwarranted public criticism. Relying on judges thoughtfully and judiciously making common law would be better than this excessive legislation. “The common law is expanded slowly and carefully by judicial decisions based on a standard of justice derived from the habits, customs, and thoughts of a people…[It is] an ideal method of building the law of a people.”[11]

The Supreme Court drew away from its 1905 Lochner philosophy in 1937. In West Coast Hotel v. Parish, it validated a Washington state minimum wage law.[12] That paved the way for a number of other pro-regulation decisions. But before long, the court also issued some anti-regulation statues, citing due process. Down to the present day, the court has varied its perspective, sometimes more supportive of applying due process to sidetrack reforms, other times more restrictive. Decisions depend on the courts’ interpretation of the “due process” clause in the Constitution.

Alton Parker is a good example of a judicial statesman, influential in his time, who wrestled with its meaning. His People v. Lochner opinion made the case for state regulatory reform upstaging due process. Rufus Peckham’s Lochner v. New York opinion made more or less the opposite point. In a sense, Parker and Peckham have been contending for more than a century, and the debate goes on.

Note: This essay draws on my book The Crucible of Public Policy: New York Courts in the Progressive Era (Albany: SUNY Press, 2022).

[1] Matthew W. Lunder,The Concept of Ordered Liberty and the Common-Law Due-Process Tradition: Slaughterhouse Cases through Obergefell v. Hodges (1872–2015) (Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2021); Adam Winkler, We the Corporations: How American Businesses Won Their Civil Rights ( New York: Liveright, 2019).

[2] Bruce W. Dearstyne, “New York’s Court of Appeals and Progressive Reform,” The Docket/Law and History Review (January 2022) https://lawandhistoryreview.org/article/bruce-w-dearstyne-new-yorks-court-of-appeals-and-progressive-reform.

[3] “Judge Parker Speaks,” New York Times July 4, 1903.

[4] U.S. Supreme Court, Allegeyer v. Louisiana, 165 US 578 (1897).

[5] “Speaking on Due Process, Judge Parker Charms Hearers,” Atlanta Constitution July 4, 1903; “Judge Parker Speaks,” Washington Post July 4, 1903.

[6] Alton B. Parker, “Due Process of Law,” American Lawyer 11 (August-October, 1903), 333-337, 388-391, 431-434.

[7] New York State Court of Appeals, People v Lochner, 175 NY 145 (1904).

[8] Bradley C. Nahrstadt’s Alton B. Parker: The Man Who Challenged Roosevelt (Albany: SUNY Press, 2024), 47-199 covers the campaign in detail.

[9] U.S. Supreme Court, Lochner v. New York (198 U.S. 45). People v. Lochner has received little study from legal historians but Lochner v. New York has gotten lots of attention, including Howard Gillman, The Constitution Besieged The Rise and Demise of Lochner Era Police Powers Jurisprudence (Durham, N.C.,: Duke University Press,1995); Paul Kens, Lochner v. New York: Economic Regulation on Trial (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1998); and David E. Bernstein, Rehabilitating Lochner: Defending Individual Rights Against Progressive Reform (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011).

[10] “Parker in Courts’ Defense,” Washington Post, September 1, 1910.

[11] Alton B. Parker, “President’s Annual Address,” American Lawyer 15 (October 1907), 469-479; Parker, “The Common Law Jurisdiction of United States Courts,” Yale Law Journal 17 (November 1907), 1-20.

[12] West Coast Hotel v. Parrish, 300 U.S. 379 (1937).