Robinson & Roberts v. Wheble (1771): A New “First” Trademark Case at Common Law

The origins of trademark law have long been disputed; some legal scholars recognize JG v. Samford or Sanford’s Case (1584),[1] later described in Southern v. How, 79 Eng. Rep. 1243 (1618) as a case in which a clothier had misappropriated his rival’s mark, as the first example of a trademark dispute in the English legal tradition. The early twentieth-century trademark scholar Frank Schecter, however, dismissed Southern v. How as an unreliably-reported outlier.[2] His view has been echoed in more recent publications, despite Professor Sir John Baker’s discovery, translation, and publication of multiple reports of Sanford’s Case four decades ago.[3]

The description of Sanford’s Case in Southern v. How may be best known to trademark lawyers from its appearance in Blanchard v. Hill, 2. Atk. Ch. (1742). There, Lord Chancellor Hardwicke distinguished the earlier case from the present issue of playing card monopolies, noting that the rival clothier had used the claimant’s mark on inferior products “with a fraudulent design” to draw away his customers. Schecter himself identified Sykes v. Sykes,107 ER 834(1824) as the first trademark case at common law.[4]

Another contender as the first trademark case at common law is Singleton v. Bolton (1783), in which Lord Mansfield presided over the first reported trademark case at the King’s Bench. Lionel Bently has ably addressed the significance of Singleton v. Bolton, while also pointing out that Lord Mansfield’s own trial notebooks and newspaper reports suggests greater trademark activity in the eighteenth-century courts than the standard historical narratives acknowledge.[5] There are indeed reports of successful passing off actions in eighteenth-century periodicals, from Dicey & Co. v. Ruffel (1755) to Greenough v. Dalmahoy (1769)and Stocker v. Anderson (1777). None of these print reports, however, can compare with the level of detailed documentation that the contemporary sources provided for the case of Robinson v. Roberts v. Wheble (1771), also presided over by Lord Mansfield and not mentioned in his notebooks.

Robinson and Roberts v. Wheble (1771) may not have been a true “first,” but it is an extraordinary, and largely unrecognized, example of eighteenth-century trademark litigation. The action saw Robinson and Roberts, the purchasers of a magazine, successful in their suit against Wheble, a printer who had used the same title and sold his product as the authentic publication. Absent from the law books, Robinson and Roberts v. Wheble has previously gone unnoticed by legal scholars, despite the rich historical record of the case and its significance as an early trademark dispute with a victorious plaintiff. Printed sources describing the case, including a published trial transcript taken down by a shorthand reporter, shed much light on Lord Mansfield’s reasoning in passing off cases, including his reference to the facts of Sanford’s Case as authority and his practice of considering both industry customs and legal doctrines in commercial disputes. While some literary scholars have discussed the case, there is much for legal historians to gain from close examination.

The Lady’s Magazine

The Lady’s Magazine was established in August 1770 by John Coote, who intended to publish monthly.[6] He engaged a neighboring bookseller John Wheble for the day-to-day publishing activity, and it was Wheble who would receive submissions to the publication. According to Coote’s testimony at trial, he had refused an initial offer from Wheble to buy a share in the magazine.

After publishing seven financially successful issues of The Lady’s Magazine, Coote sold his interest in the business to booksellers Robinson and Roberts for the considerable sum of five hundred pounds. Following their purchase, Robinson and Roberts used many of the same authors and kept the same compiler and printer, but they chose a different publisher instead of Wheble. This decision may have been influenced by the knowledge that Wheble was under fire for illegally publishing Parliamentary Reports.

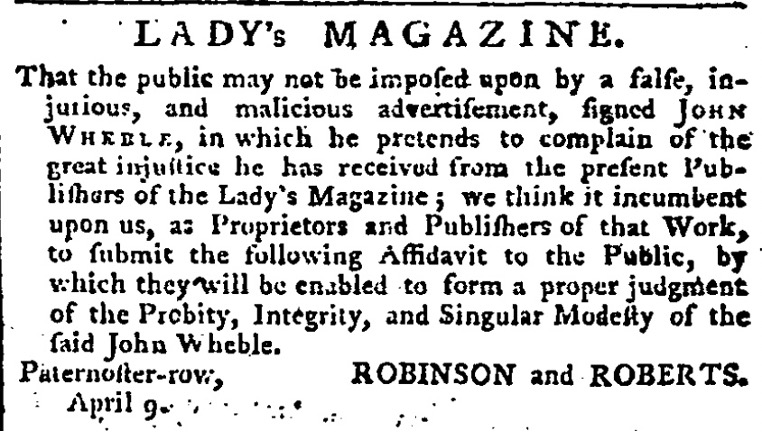

The next issue, or “number,” of The Lady’s Magazine was to be the eighth. One of the key attractions of the publication was a serial work by an anonymous author called “The Sentimental Journey,” and Robinson and Roberts assured their reading public that this story would be continued in the new eighth issue under their direction.[7] Wheble responded with his own advertisements appealing “to the Ladies” as the “original publisher” of the Lady’s Magazine, claiming that the issue soon to be published by Robinson and Roberts was “spurious” and “formed to deprive him of the honest emolument of his publication.” He pleaded with the public not to “permit any other Magazine in imitation of his, to be obtruded on them.”[8]

Robinson and Roberts responded with further advertisements contesting Wheble’s claims, even including an affidavit from Coote asserting them as the rightful owners.[9] Eventually, the partners turned to the law, bringing an action of trespass against the case against Wheble. Their claim asserted that they had purchased Cootes’s interest in the magazine “in full confidence that sort of property, in the view of the whole trade, was not to be invaded by any of those, who knew in their consciences it had been in the possession of them.”[10] Their attorneys sent a clerk to Wheble’s shop to purchase copies to be used as evidence; the clerk later testified that Wheble claimed his “was the true Lady’s Magazine, the original Magazine, and there were others out that were bad.”[11]

The case was tried at Guildhall before Lord Chief Justice Mansfield and a special jury on Monday, July 8, 1771. Counsel for the plaintiffs used Wheble’s own words from the advertisement to show that he too had recognized the magazine as “property.” Many witnesses were called, including the magazine’s printer John Johnson and its founder Coote for the plaintiffs. Coote gave evidence pertaining to his sale of the magazine to Robinson and Roberts, producing the receipt that he had “[r]eceived 18th March, 1771 the sum of 500l. for the Lady’s Magazine, an assignment of which is to be made when required.”[12]

A bookseller in St Paul’s Churchyard was called as a witness to establish the custom of the trade; he asserted that rights to publish a magazine were regularly bought and sold as property and that he had given “two hundred and four score pounds for the eighth part of a Magazine.”[13] Other witnesses also established the trade custom of buying and selling, as well as inheriting, shares in periodical publications.

Defendant’s counsel tried to frame the case as a flimsy claim in a nonexistent copyright and to bring into question the legitimacy of the financial transaction. Lord Mansfield, however, was careful to distinguish the right at issue in the case—and its limitations—from copyright. While periodical titles at this time were often very similar and did not alone constitute property as such, Wheble had repeatedly made misleading claims to the public that his magazine was the true continuation of the original. In the eminent jurist’s view, Wheble’s misrepresentation that his ninth issue was a continuation of the original publication and his accusations that the plaintiff’s magazine was fraudulent formed a basis for the plaintiffs’ action. In his instructions to the jury, Lord Mansfield articulated the basis for liability in terms strikingly familiar to the ears of modern intellectual property lawyers. Wheble had:

made use of his mark to take the benefit from him, and representing his as being the Original and the other Spurious; therefore he does an injury to the Plaintiff. Therefore an action lies.—With regard to dealing in cloth, suppose one puts a lion’s head and three stars upon it, if another puts a lion’s head and three stars, he may sell it, that would not hurt the original maker, but if he was to say, I am the original maker of all such cloth mark’d with such mark, it would hurt the first person who put such mark. Upon that ground you will find a verdict for the Plaintiffs.[14]

Lord Mansfield’s example of selling one’s cloth as another’s cloth, resulting in damage to the original seller, clearly refers to the facts and holding from Sanford’s Case as articulated by Lord Hardwicke in Blanchard v. Hill.

While recognizing that there was a property right at issue, in Lord Mansfield’s view, it was through the deception of the public that the right was violated. “Upon this sort of property, if there was not a promise of assignment, it is sufficiently conveyed by a receipt in full for the right to the copy”—the property which had clearly been sold by Coote to Robinson and Roberts. Wheble was free to set up a rival publication, but he could not claim “his No. 9 [issue of The Lady’s Magazine] was a continuation of the original work, of which eight numbers had been sold” because to do so was “a fraud.”[15]

The jury shared Lord Mansfield’s opinion that Wheble had sold his version of The Lady’s Magazine as that which was now owned by Robinson and Roberts. Without evidence of damage to the plaintiffs, only nominal damages of one shilling were assessed. Neither side was particularly happy with the outcome in the case, as both parties had wanted to be recognized as the sole, legitimate owner of a property right in selling a publication called The Lady’s Magazine. As it was, both publications continued in competition for several months until Wheble’s version eventually folded in 1772.[16]

Reports of the Trial

Wheble’s next issue of The Lady’s Magazine included a full transcript of the trial before Lord Mansfield accompanied by footnotes detailing his own objections, criticisms, and general outrage. The news section of the issue of also included a brief summary of the case.[17]

The twelfth issue of Robinson and Roberts version of the Lady’s Magazine was not quite as thorough in its documentation of the court proceedings, but it included an editorial by the publishers, and a short report of the case in the “Home News” section. The report emphasized Lord Mansfield’s comparison of Wheble’s actions with “one man selling cloth by another man’s mark.”[18]

The report of Robinson and Roberts v. Wheble in The London Gazette of July 9, 1771 also noted Lord Mansfield’s reference to a clothier using another’s mark:

Monday was heard, before Lord Mansfield at Guildhall, a cause founded on a plea of trespass on the case. Messrs. Robinson and Roberts, book-sellers in Paternoster-row, were the plaintiffs, and Mr. John Wheble, of the same trade and place, was the defendant. The plaintiffs brought their action against the defendant for continuing to sell and publish the Lady’s Magazine, after they had purchased it for the valuable consideration of 500l. of Mr. Coote, who originally planned the work, and, before he disposed of his right of it, had employed the defendant as his publisher. Mr. Dunning, Council for the plaintiffs, remarked, that the defendant, not content with barely continuing the work, had publicly asserted in his appeal to the Ladies, that his was a continuation of the original genuine work, and the plaintiffs had imposed upon the world a spurious Lady’s Magazine, to his manifold injury and prejudice. In the course of the trial, it was declared by his Lordship from the Bench, that the selling of one Magazine for another, under the same title, was a fraud and an imposition upon the public of the same nature as one man selling cloth by another man’s mark. After examining many respectable witnesses in the trade, the Jury brought in a verdict with one shilling damages, in favour of the plaintiffs.[19]

Thus, the historical record demonstrates Lord Mansfield’s use of the sixteenth-century precedent of Sandforth’s Case in at least one eighteenth-century passing off action.

Significance of Robinson and Roberts v. Wheble

The case of Robinson and Roberts v. Wheble provides legal historians with the most thorough documentation of an eighteenth-century trademark dispute on the record and a glimpse of Lord Mansfield’s innovative jurisprudence in action. Furthermore, it provides strong evidence that the holding of Sanford’s Case continued to be cited with approval by the courts between Blanchard v. Hill (1742) and its apparent reemergence in mid nineteenth-century trademark doctrines. Perhaps the case can also serve as a reminder to legal historians to look beyond the law in their search for primary sources—such sources may even be found in publications designated “solely” for the “use and amusement” of “the fair sex.”

[1] “JG. v. Samford” in Baker and Milsom, Sources of English Legal History—Private Law to 1750, ed. John Baker (Oxford University Press, (2nd ed. 2010), 673-676. There are many spelling variations for the name of the case, including Samford’s Case, Sandforth’s Case, Sandforde’s Case, Sandford’s Case etc.

[2] Frank Schecter, The Historical Foundations of the Law Relating to Trade-Marks (New York: Columbia University Press 1925), 6-9.

[3] Keith M. Stolte, “How Early Did Anglo-American Trademark Law Begin? An Answer to Schechter’s Conundrum,” 8 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 505 (1997).

[4] Schecter, Historical Foundations, 137.

[5] Lionel Bently, “The First Trademark Case at Common Law? The Story Of Singleton v. Bolton (1783),” 47 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 969 (2014), 970, 1013.

[6] Jennie Batchelor, The Lady’s Magazine (1770-1832) and the Making of Literary History, (Edinburgh University Press 2022), 42-43.

[7] “Advertisements and Notices,” Middlesex Journal, April 30, 1771 – May 2, 1771.

[8] “News,” General Evening Post, April 9, 1771 – April 11, 1771.

[9] “Advertisements and Notices,” General Evening Post, April 13, 1771.

[10] The Lady’s Magazine (Wheble), July 1771, 42.

[11] Ibid, 48.

[12] Ibid, 46.

[13] Ibid, 49.

[14] Ibid, 50.

[15] Ibid, 52.

[16] “The Lady’s Magazine,” British Literary Magazines: The Augustan Age and the Age of Johnson 1698-1788, ed. Alvin Sullivan (Greenwood Press 1983): 183.

[17] “Home News,” The Lady’s Magazine (Wheble), July 1771: 54.

[18] “Home News,” The Lady’s Magazine (Robinson & Roberts), July 1771: 573.

[19] The London Gazette (July 9, 1771).