Jeffery Jenkins and Justin Peck kindly agreed to discuss their new book Congress and the First Civil Rights Era, 1861-1918 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021), with The Docket. They had previously published a major article in Law & History Review entitled, “Building Toward Major Policy Change: Congressional Action on Civil Rights, 1941-1950” (vol. 31, no. 1, 2013). Below we discuss the origins of their project, some of their main arguments and interventions and more.

The Docket [TD]: Hi Jeffery and Justin, thanks very much for taking the time to discuss your new book for our readers. Our first question is about the origins of this project. Can you tell our readers how you came upon this topic, and how you decided to collaborate on it?

Jeffery Jenkins and Justin Peck [J&P]: Typical histories of civil rights in America often talk about what happened after the Civil War – during Reconstruction – and what happened in the 1950s and 1960s. Left largely undiscussed is congressional (in)action on civil rights between these periods. We talked about this while we were both at the University of Virginia — Jeff as a professor and Justin as a PhD student — and we wanted to answer that basic question. With the help of Vesla Weaver, we subsequently wrote and published an article looking at the period between 1890 and 1940. We found that there were efforts to engage civil rights in Congress during this period, but often with little to show for it.

Once we wrote that article, we became increasingly interested in the story of civil rights legislation in Congress from the outbreak of the Civil War to the present. There was no analytical history that covered this entire period, and we thought the topic was important and needed to be understood. Thus, we decided to write a book. Before long, we saw that analyzing the entire period was going to be really unwieldy, especially if we wanted to cover the details of particular legislative efforts in depth. In time, we determined that the project could be split into two books, with the break point occurring in 1918, at the end of the first World War.

TD: Regarding the book, you are making a bold argument about the origins and experience of “the first civil rights era.” What do you mean by that phrase “first civil rights era,” both in terms of how it came about, and how we should understand it in connection with subsequent ‘civil rights eras.’

J&P: While writing the first book, we eventually came to the idea that since the Civil War there have been two civil rights eras (or “arcs”). At the beginning of each era, civil rights initiatives win the necessary support to be enacted into law. By the end of each era, the enacting coalitions responsible for them collapse and they are either repealed outright, ignored, or slowly weakened. The first civil rights era covers the 1861-1918 period and forms the basis of this first book. The second civil rights era covers the 1919-1990 period, and is the basis for the second book, which we are now writing.

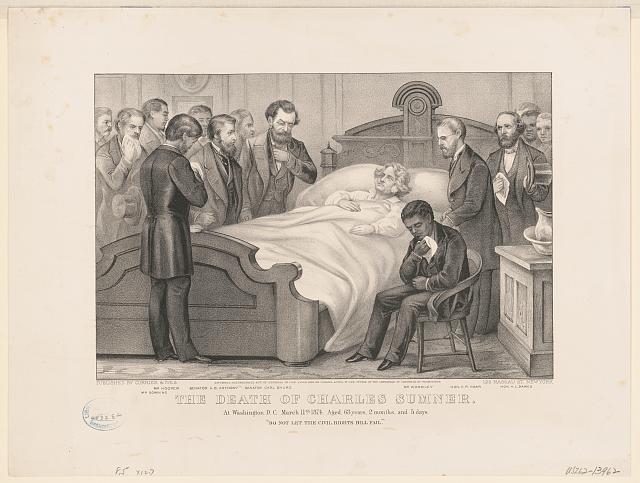

The first civil rights era is a true “arc” in the sense that there is a rise, a peak, and a fall. Slavery was eradicated, former slaves were given the right to vote in the South, and that helped lead to foundational civil rights achievements like the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. But those achievements were not durable. As the Democrats in the South returned to power, and white opinion in the North turned away from further support of civil rights, civil rights advocates found themselves with few reliable allies. New initiatives focusing on education and enhanced protection of voting rights in the South failed in Congress, and enforcement laws created to support earlier initiatives were repealed. Eventually, Jim Crow laws (supporting segregation) and disenfranchisement legislation were adopted throughout the South. And national Republican politicians eventually gave up on protecting Black rights in favor of sectional reconciliation. This was the civil rights “nadir” in the post-Civil War era.

The second civil rights era is similar in that there is an arc with a rise and a peak. But the fall is more gradual. The rise starts with the Civil Rights movement in the 1950s and new civil rights laws in 1957 and 1960. The peak occurs in the mid-1960s with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The fall, we argue, begins with the Civil Rights Act of 1968, continues with the anti-busing debates in the 1970s and early 1980s, and culminates with the failure of the Civil Rights Act of 1990. In some sense, the back-end of the second civil rights era is more a story of failed momentum and lack of continued progress than one of outright repeal. Although, if we were to take the story up through the present day (as we plan to in the second book’s conclusion), there are signs that true erosion of voting-rights gains in the South might be occurring.

TD: Much of the analysis focuses on the Republican Party and its willingness, at least for a while, to emphasize the theory and enforcement of civil rights legislation. Why was the “Grand Old Party” (GOP) so committed to a substantive program of civil rights, and why did that commitment fade over time?

J&P: The Republican Party began as an anti-slavery party — specifically, a party opposed to the extension of slavery into the territories — in the 1850s. When the GOP came to power during the Civil War, they ultimately came to believe that the eradication of slavery was crucial to winning the war. After the war, they were faced with sectional reconciliation and developing a policy to deal with the new “freedpeople” in the South. In short order, some Republican politicians saw that granting the former slaves voting rights would help ensure their safety and survival — and create a new class of Republican voters (and states) in the South.

More specifically, when Republicans controlled Congress following the war, and when a majority of them believed their political fortunes were contingent on the support of Black voters, they passed civil rights initiatives. As Union troop levels in the occupied former Confederate states dropped after 1868, however, white elites in the South orchestrated a systematic campaign of violence and political terrorism against Black voters. The constant “drama” coming out of the South — often covered in lurid detail by partisan newspapers — amid a nationwide economic downturn in the 1870s ultimately turned the Northern white public against civil rights. As Northern opinion shifted, Republicans in Congress neglected and undermined those policies they had once advocated. And though federal authorities fought Southern white reactionaries for a time, violence and intimidation were ultimately successful in dampening Black political participation and culminated in the “redemption” of Southern state governments.

Taken together, conflict within the Republican Party regarding the use of federal power to protect the Black minority and electoral trends driven by shifting white attitudes in the North explain the rise and fall of what we call the “first civil rights era.” In the immediate aftermath of the war, the GOP served as a mechanism for advancing and defending Black freedom. Yet the progressive disenfranchisement of Black voters in the South, while the Northern public sought to refocus attention on economic issues that were central to their concerns, persuaded many congressional Republicans to withdraw their support for civil rights. As the electoral influence of Black voters declined, the political power of those within the GOP who opposed expansive federal authority to protect Black freedom grew. By the second decade of the twentieth century, the Republican Party had almost entirely abandoned its historic support for the protection and extension of Black civil rights.

TD: Methodologically speaking, the focus on the United States Congress is interesting and a bit different from much of the relevant scholarly literature–”an explicitly Congress-centered perspective,” (300) you call it. Can you discuss what you mean by this concept and what the advantages are in pursuing this kind of approach?

J&P: We focus on Congress because it was the preeminent branch of the national government during the period in question and was formative in defining and enforcing civil rights protections. The constitutional questions at stake ensured a role for the president and the Supreme Court, but during the first civil rights era they were most often reacting to decisions made by Congress. Thus, to understand the behavior of a president or the Supreme Court during this era, we argue that we must first understand how and why Congress enacted the policies it did.

We also focus on Congress because it allows us to explore the ways politics and policy were linked, as well as the relationship between ideas and interests. For example, we argue that congressional debate clarifies how lawmakers thought about the relation between civil rights and the Constitution from the Civil War through the second decade of the twentieth century. The arguments members of Congress made were published in newspapers and otherwise communicated to constituents. They both reflected and influenced public opinion. When written into policy, these ideas shaped subsequent politics concerning civil rights.

TD: Do you think that the story you tell in this book can help people make sense of the contemporary political world?

J&P: We think that there are definitely insights on civil rights conversations of today.

One big insight is: laws aimed at protecting the civil rights of Black citizens are never self-enforcing and they are rarely durable. Even when a law is enacted, the story doesn’t end. We find that most often additional laws are adopted that strengthen and expand the rights specified in landmark achievements. At the same time, successful enactments also generate opposition movements aimed at eroding – or even eliminating – those rights.

As noted above, as we complete the second book, we think a big part of what we’ll write about – in terms of the second civil rights era – will focus on how various types of civil rights policy (especially voting rights) have become contested terrain. For example, liberals want to make it as easy as possible for people to vote while conservatives want to establish more stringent parameters.

“We think that there are definitely insights on civil rights conversations of today.”

Another big insight is: federalism is an underappreciated aspect of civil rights policy. One thing that has hindered the enactment of national civil rights policy is the strong history we have on decentralized decision making in the United States, and the value we place on making policy “close to home.” So much of the battle on voting rights policy today, for example, is conducted at the state level, with “red states” and “blue states” pursuing different paths. Congress has the ability to produce federal policy, but the strong states’ rights interests that shaped civil rights policy in the late-19th century and the mid-20th century still operate today. Recent decisions by the Supreme Court have eroded federal voting rights law and opened up new ways for states to fill that power vacuum. Congress has mostly abdicated and let states make their own decisions.

The last big insight concerns the consequences of territorial representation. For much of American history, Black citizens were most heavily populated in the South. As a consequence, they relied for political support on legislators who were not from their states or districts. This ensured that elite advocacy for Black civil rights always hinged on strong levels of support from northerners who were happy to enforce civil rights laws in the South, but were less willing to apply those same laws to their own constituents.

TD: For our final question, let’s end with a fun one. Recommend to our readers your favorite non-scholarly website or podcast and let us know why we should check it out.

Jeff: I don’t really listen to podcasts! But I’m a big sports fan. So I’m often on ESPN.com. And I’m a big Chicago Cubs fan, so I’m often on Bleacher Report.

Justin — I’m a big fan of George R.R. Martin’s fantasy series, A Song of Ice and Fire. For any readers who are also fans, I recommend the NotACast Podcast for deep analysis of the books, show, etc.