In August of 1973, Justice Harry A. Blackmun addressed the American Bar Association at its annual prayer breakfast. Blackmun referenced the biblical story of Nehemiah, who upon return from Babylonian exile discovered Jerusalem in ruins. “The pall of Watergate,” Blackmun told the audience was similar. “There is a sadness all about us … The very glue of our government structure seems to have become unstuck … which will prevail – the ‘better angels of our nature’ – to use Mr. Lincoln’s words, or something far less.”[1]

His fellow justices shared his concern. In an annual summary of the Court’s proceedings known as case histories found in the papers of William J. Brennan in the Manuscript Division at the Library of Congress, Justice Brennan revealed that members of the Court had been following the controversy and were attentive to its possible ramifications: “I was not the only Justice who many months before had prepared the groundwork.” For Brennan, it was time for the “Nation to have access to the evidence” such that the people would know the “truth about Watergate.” “Decisive action” by the Court, he wrote, promised to bring things to a conclusion enabling the country to “heal its Watergate wounds.” Brennan dismissed out of hand administration arguments that maintained “an early grant of certiorari would lead to a hasty, ill-conceived decision,” such admonishments were simply a “bugaboo.”[2]

The fiftieth anniversary of United States v. Nixon (U.S. v. Nixon) occurs this summer, while the Court deliberates on a similar case involving a former president. The machinations of the Court five decades ago provide insight into the decision that thwarted Nixon, but also codified the idea of executive privilege. The case also provides a window into the Court’s relationship with the media, unfolding political scandal, and the dynamics of such cases between sitting justices.

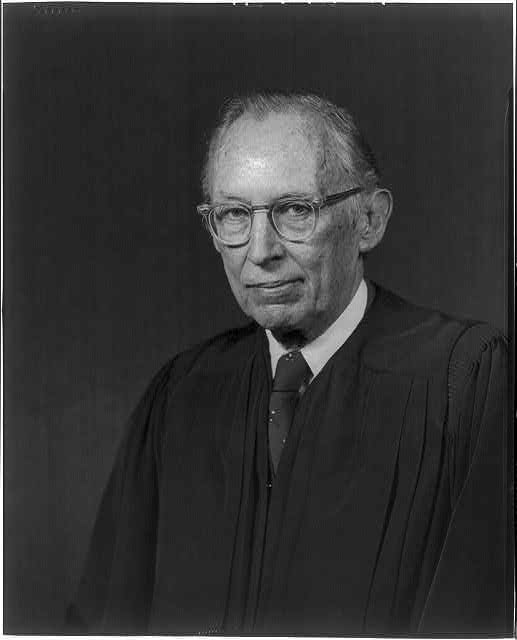

One of the first inside accounts of U.S. v. Nixon emerged in the controversial best seller by Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong, The Brethren, published in 1979, five years after the decision. Though numerous aspects of the clerk driven book remain questionable, in his oral history, Justice Blackmun, who admitted he didn’t consider The Brethren to be “very good”, acknowledged its accuracy, expressing surprise at “the detail set forth in the book.”[3]

While many observers pointed fingers at Brennan as the source, the justice denied any connection to the two journalists. “I have never met either Woodward or Armstrong. I have never talked with them or either of them personally or by telephone. I have never been interviewed by them or either of them,” Brennan wrote to New York Times columnist Anthony Lewis in mid-January of 1980. He further denied that he had ever provided the two men with any “files or case histories.”[4] Instead, if Justice Blackmun is to be believed, Justice Potter Stewart served as a, perhaps, the main source for the two writers. “I think the so-called leaks …. were attributable to” Potter, who Blackmun added “was always friendly with the press, he liked the press, they liked him, he was a good subject.”[5]

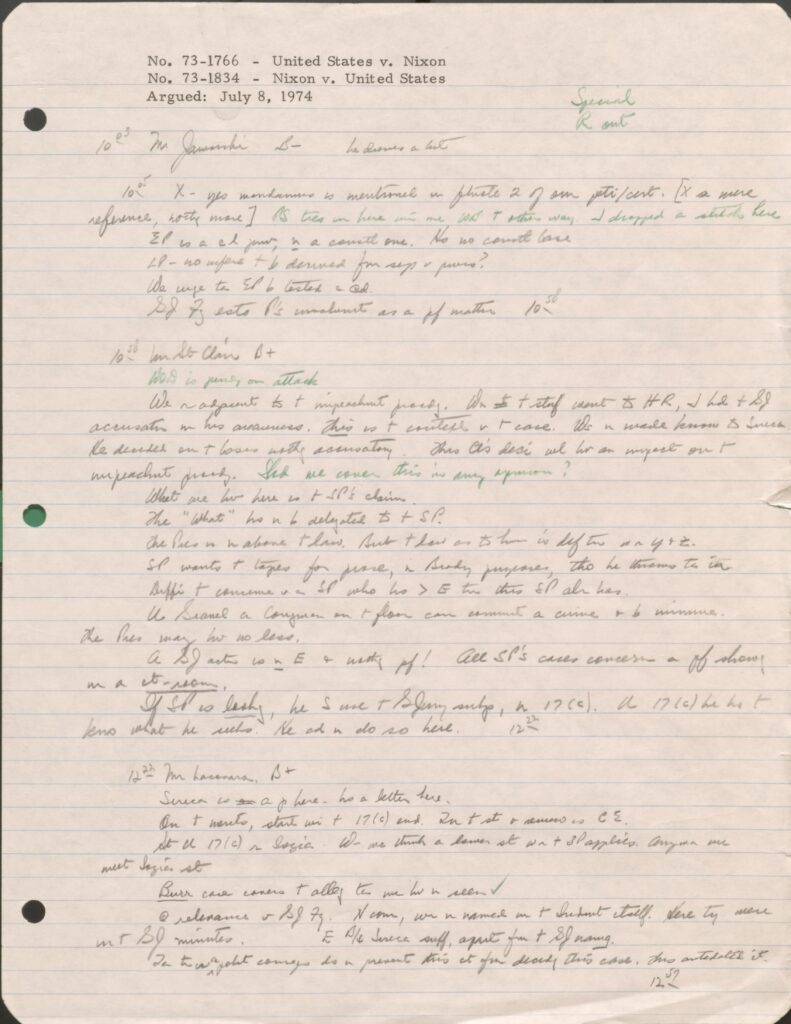

In their narrative, Woodward and Armstrong describe the activities of seven justices, William Rehnquist recused himself, circulating around Chief Justice Warren Burger. From the first seconds of conference, Burger expressed an intent on writing the opinion, one that, according to Linda Greenhouse and Michael J. Graetz, depended heavily on the precedent established by Chief Justice John Marshall in the trial of Aaron Burr, United States v. Aaron Burr (1807). Brennan had attempted to build support among the justices about the possibility of a joint opinion process which was dashed by Burger’s decision.

Burger was not alone in his dependence on the Burr case, the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia also cited it in its decision. Blackmun gave the ruling consideration, drafting a three-page memorandum to himself regarding its import. “Chief Justice Marshall obviously was in unfamiliar ground and in effect plowing virgin territory,” recognizing this Marshall “protected his flanks,” wrote Blackmun. The president is not immune from subpoena. For Blackmun “the right of the accused” served as “the central theme of this opinion.” Yet, while the president deserved special consideration in this regard, “the court has a duty to protect the President from vexatious subpoenas … the executive was not above judicial review.”[6]

Blackmun aside, his fellow justices failed to grasp “the parallel that Burger saw between” the two cases, nor Burger’s passion in ratifying Marshall’s decision. “Had his colleagues understood this, they might have wasted less energy trying to wrestle the Nixon opinion away from him,” speculated Greenhouse and Graetz.[7]

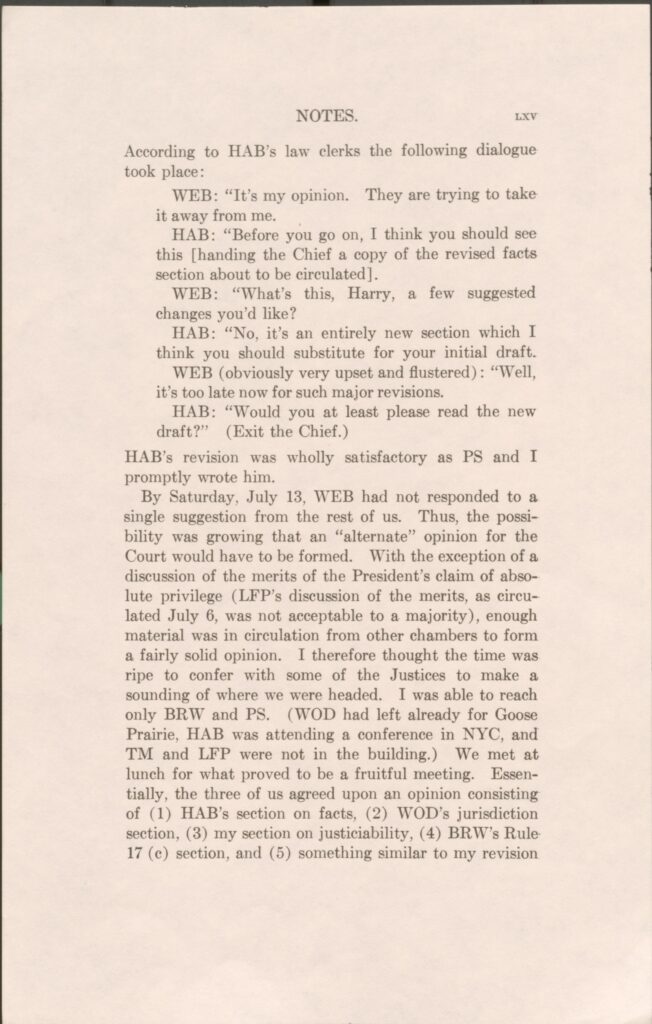

Wrestle it away they did however. None of the justices wanted Burger to write the opinion. If Nixon were impeached, the chief justice would preside over the trial in the Senate. Moreover, Brennan noted, “the CJ had often displayed an unwillingness to change opinions he authors.” Nixon had indicated before the trial that he would abide by a “definitive” ruling, a point that concerned Brennan since he believed if Burger were to author the opinion, “the Court might end up with several opinions supporting a unanimous result, hardly a ‘definitive’ resolution.”[8]

Through memorandum and the occasional private conference, the participating justices addressed various aspects of the case, dividing the six specific issues between them: (1) the facts, (2) justiciability, (3) appealability, (4) Rule 17 (c), (5) executive privilege, and (6) executive privilege.[9] Burger resisted their advice repeatedly, but eventually gave in, incorporating and in many instances adopting the work of his colleagues in the final opinion.

According to Brennan’s account, Justice Lewis Powell shined the brightest. Powell, designated LFP by Brennan in his case histories, had drafted the section on executive privilege. Powell’s initial draft did not secure the support of the other justices. They were troubled by his argument that the legitimacy of executive privilege could be determined according to “which branch had the greatest particularized interest.” Benjamin S. Sharpe, who clerked for Blackmun that term concurred. “I don’t think LFP’s section was well received … I would guess that people will go along with this if the requested revisions are made.”[10]

Clearly, Brennan, who played a key role in the decision throughout, found this unsettling as well. He and the others thought Powell could revise the section, and it could serve as the “basis of the Executive Privilege” portion of the final opinion. Powell was open to debate and revisions in which Brennan assisted. While the edits hung on several details, the fundamental idea came down to a fairly simple concept: “even in the areas of national defense, etc., we should hold that the judiciary would be the final decisionmaker – not the Executive branch.”[11] Brennan gushed about Powell’s adaptability: “LFP’s magnificent approach to decision making – that he should do his utmost to find common ground with his brethren without sacrifice of basic principles – was never more evident.”[12]

Burger’s resistance to these efforts may have been an expression of his personal frustration with his inability to control the conference. “I think he was upset … with the way the thing was working, because very little of his opinion was automatically accepted,” Blackmun commented in an oral history contained in his papers. Blackmun, whose responsibility entailed a rewriting of the statement of facts, drew the ire of the chief justice. Blackmun believed Berger “resented” his role in the decision. “It was a situation that was built for resentments and misunderstandings and certainly developed them.” Between the Roe v. Wade decision during the previous term and U.S. v Nixon, the two men’s paths, which had converged during their childhoods in St. Paul, Minnesota, diverged. The case functioned as a “signal event in the dissolution of the friendship” between the Minnesota Twins, as they were sometimes dubbed, writes Greenhouse.[13]

Eventually, by July 23, an opinion, crafted by each member of the Court but credited to the chief justice, had been willed into existence. Even in this, there was debate. Demonstrating a grasp of national politics, Powell questioned when the decision should be announced. Powell noted that several congressman and pundits had suggested the GOP members of Congress might use a negative decision to delay impeachment. If that occurred, it could interfere with congressional impeachment proceedings if “the decision requires the President to disgorge new evidence, it would be argued then the committee should not vote until it has had time to assess the evidence.”[14] Ultimately, the Court decided to issue the ruling on the 24th without delay. “[T]here are always political repercussions for a decision of the Supreme Court,” Brennan wrote, “and the only safe course for the Court, for its prestige and for its image in the minds of the American people is to ignore them completely and announce a decision when it is ready.”[15]

In his case history, Brennan hailed the decision as “a collegial product in the best sense of that term.” Delivered by the chief justice, it was a product of all eight participating justices. “That is why in only 16 days-time, the Nation had a unanimous, definitive decision on a question of greatest movement to the Nation.” Years later, however, Blackmun wondered. “I’m not sure it’s a very good opinion. One could hardly be written and be good under the circumstances as they existed … but it was acceptable and got by.”[16]

In general, legal experts agree with Blackmun. The decision enabled prosecutors to gather evidence that adversely impacted defendants by “overriding a constitutional privilege in order to make it possible to prove their guilt. However, plenty of examples of common confidential legal privileges exist: attorney-client, husband-wife, and physician-patient to name three. State and federal courts have struggled to square the ruling with these “far more ordinary circumstances,” observe Greenhouse and Graetz.

Yet, whatever its juridical value, the decision “got the politics right.” Nixon had demonstrated his criminality; his resignation which followed in August, “was well deserved.” With Ford’s pardon of Nixon, the nation had avoided a painful impeachment trial. Moreover, the decision while deleterious for Nixon, actually strengthened the presidency. Executive privilege was ratified and succeeding presidents have drawn upon it. It also shielded presidents from civil damages “for wrongful acts committed while in office.” The office of president emerged stronger than ever.[17]

Before Trump v. Anderson this term, the most immediate and closest parallel to U.S. v Nixon was the Bush v. Gore decision in 2001, when the conservative majority cobbled together a narrow and controversial opinion regarding the 2000 presidential election. According to Evan Thomas, Sandra Day O’Connor offered a similar critique in 2001, telling one of her former clerks that she regretted the decision, which though far from “a collegial product” did resemble a similar all hands-on deck approach, at least among the Court’s more conservative justices.[18]

Justice Stevens who dissented in the case drew direct comparisons to U.S. v. Nixon writing in his memoir, that the earlier case had burgeoned the Court’s standing, but that the Court had yet to recover from the 2001 decision.[19] When told of O’Connor’s 2016 comments, Stevens responded “She voted incorrectly. She made a terrible mistake.” In 2017, when asked if she had regrets, O’Connor admitted that she did but that “second thoughts don’t do you a lot of good. It looked like a party-line vote, I know.”[20] In contrast, in U.S. v. Nixon, the justices ruled 8-0 against the president even though it was widely seen as Nixon’s Court. He had appointed four of Court’s nine members: Burger, Blackmun, Powell, and Rehnquist.

The media’s coverage of the case did not go unnoticed by the Court. A New York Times article, published after the decision and immediately before Nixon’s resignation, drew the attention of the justices, possibly due to the chief justice’s role in creating it.

Barrett McGurn, a Supreme Court spokesperson, told the New York Times that the case had been assigned to Burger on July 9, without controversy, and that the chief justice had from the start, opposed Nixon’s argument. McGurn also refuted rumors that Burger had tried to convince his fellow justices that Nixon had the right to withhold the tapes from the special prosecutor. According to McGurn, Burger and his clerks worked for 41 consecutive days “often worked without leaving the Chief Justices office, eating a picnic lunch that was generally prepared by Mrs. Burger.”[21]

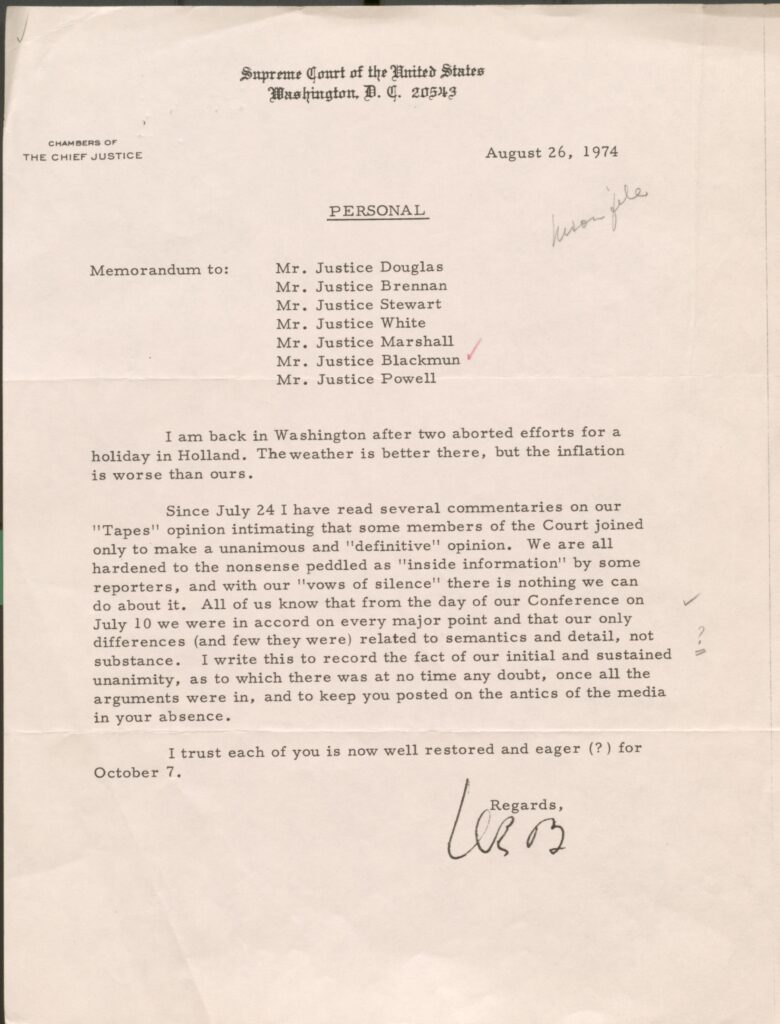

When the justices returned from their break in late August, Burger greeted them with a memorandum labeled “Personal.” After the decision, the chief justice had read several “commentaries” on the tapes case “intimating that some members of the Court joined only to make a unanimous and ‘definitive’ opinion. We are all hardened to the nonsense peddled as ‘inside information’ by some reporters and with our ‘vows of silence’ there is nothing we can do about it.” Burger continued dismissing the narratives put forth by Blackmun, Brennan, and The Brethren. “All of us know that from the day of our Conference on July 10 we were in accord on every major point and that our only differences (and few they were) related to semantics and detail, not substance.” The Court’s “unanimity … was at no time in any doubt.”[22]

For his part Brennan stated, “the reader of this history must decide for [themselves] whether [they share] the opinion of the Chief Justice,” but he added Burger claimed the opinion from the first moment, “killing off the effort to have all members sign the joint opinion.” As for the drafting of the decision, the primary obstacle was throughout Burger’s resistance to other drafts before accepting and adopting them when it was clear that a clear majority favored their drafts to Burger’s.[23] The chief’s statement drew a simple question mark from Blackmun.

A brief postscript: a few months later, President Ford, in testimony before the House Judiciary subcommittee, mentioned the ruling this time to defend executive privilege from congressional interference. “In the United States v. Nixon the Supreme Court unanimously recognized a rightful sphere of confidentiality within the executive branch of the government which the court determined could only be invaded for overriding reasons of the Fight and Sixth Amendments,” a point Anthony Lewis found vexing. Sure, he wrote in a letter to White House counsel Phillip E. Areeda, the ruling was more or less limited to judicial inquiries by subpoena and made no judgment on the legislative branch’s power in this regard. “It certainly did not determine or even faintly suggest what sorts of Presidential materials Congress might rightly see,” Lewis wrote. “I do not like to see that case misused by a President – any President – as a weapon in his relations with Congress. Those ever-present issues of access to information should be worked out in terms of common sense and accommodation, not be reference to judicial authority that does not exist.”[24]

In testament to Lewis’s sway, Areeda responded, admitting that yes, the issue of Congress had not become before the Court, but that the New York Times columnist, would agree “that the access issue must be worked out in terms of common sense and accommodation.” The President and advisors, the Court acknowledged, required a level of “confidentiality to facilitate candid advice within the executive branch. The Court’s opinion certainly spoke of that need and in rather broad language.” Moreover, the ruling was not entirely irrelevant to “Congressional demands.” A true resolution, Areeda wrote, can only be found in the adjudication of “concrete cases.” After all, how does one balance the need for transparency while acknowledging that individuals working with and advising the President require a certain level of candidness to truly serve the country. As a nation, we continue to search for this equilibrium.

[1] Linda Greenhouse, Becoming Justice Blackmun: Harry Blackmun’s Supreme Court Journey (NY: Times Books, 2005), 122.

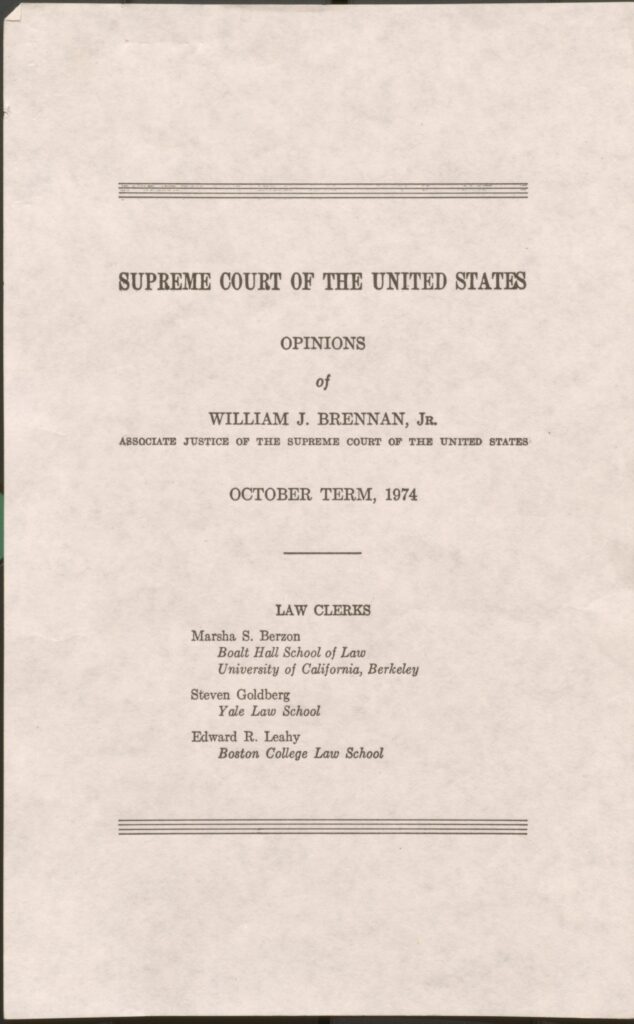

[2] William J. Brennan Marsha S. Berzon, Steven Goldberg, and Edward R. Leahy, “Opinions of William J. Brennan, October Term 1974,” p. XLIV Box II:6, William J. Brennan Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[3] Harry A. Blackmun, “The Justice Harry A. Blackmun Oral History Project,” Harold Hongju Koh interviewer, July 6, 1994 – December 13, 1995, p. 224. Box [1429], Harry A. Blackmun Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[4] William J. Brennan to Anthony Lewis, January 14, 1980, Box 197, folder 5, Anthony Lewis Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[5] Blackmun, “The Justice Harry A. Blackmun Oral History Project,” 224.

[6] Harry A. Blackmun, memorandum: United States v. Burr, 25 Frd. Cas. 30 (D. Va., Marshall, C.J. sitting as Circuit Justice), June 20, 1974, Box 191, Harry A. Blackmun Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[7] Linda Greenhouse and Matthew J. Graetz, The Burger Court: The Rise of the Judicial Right (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016), 335-337.

[8] William J. Brennan Marsha S. Berzon, Steven Goldberg, and Edward R. Leahy, “Opinions of William J. Brennan, October Term 1974,” p. LIX Box II:6, William J. Brennan Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[9] William J. Brennan Marsha S. Berzon, Steven Goldberg, and Edward R. Leahy, “Opinions of William J. Brennan, October Term 1974,” p. LII, Box II:6, William J. Brennan Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

[10] Benjamin S. Sharpe, memorandum No. 73-1766/No. 73-1834, July 18, 1974, Box 191, Harry A. Blackmun Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[11] William J. Brennan Marsha S. Berzon, Steven Goldberg, and Edward R. Leahy, “Opinions of William J. Brennan, October Term 1974,” p. LVIII, Box II:6, William J. Brennan Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[12] William J. Brennan Marsha S. Berzon, Steven Goldberg, and Edward R. Leahy, “Opinions of William J. Brennan, October Term 1974,” p. LXIX, Box II:6, William J. Brennan Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[13] Blackmun, “The Justice Harry A. Blackmun Oral History Project,” 228-229; Greenhouse, Becoming Justice Blackmun, 122.

[14] William J. Brennan Marsha S. Berzon, Steven Goldberg, and Edward R. Leahy, “Opinions of William J. Brennan, October Term 1974,” LXXXII, Box II:6, William J. Brennan Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[15] William J. Brennan Marsha S. Berzon, Steven Goldberg, and Edward R. Leahy, “Opinions of William J. Brennan, October Term 1974,” p. LXXIII Box II:6, William J. Brennan Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

[16] Blackmun, “The Justice Harry A. Blackmun Oral History Project,” 230.

[17] Greenhouse and Graetz, The Burger Court, 337-338.

[18] Evan Thomas, First: Sandra Day O’Connor (New York: Random House, 2019) 339.

[19] John Paul Stevens, The Making of a Justice: Reflections on My First 94 Years (New York: Little: Brown & Company, 2019), 374.

[20] Thomas, First: Sandra Day O’Connor, 339.

[21] “Burger Worked 41 Straight Days on Nixon Case,” New York Times, August 6, 1974.

[22] Warren Burger to Justices Douglas, Brennan, Stewart, White, Marshall, Blackmun, and Powell, August 26, 1974, Harry A. Blackmun Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[23] William J. Brennan Marsha S. Berzon, Steven Goldberg, and Edward R. Leahy, “Opinions of William J. Brennan, October Term 1974,” p. LXXXIII-LXXXIV, BoxII:6, William J. Brennan Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

[24] Anthony Lewis to Phillip E. Areeda, October 30, 1974, Box II: 75, Anthony Lewis Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.