[Ed. Note. This fall, Law and History Review’s Editorial Assistant, Elinor Aspegren, had the opportunity to discuss Professor Sarah Balakrishnan’s fascinating work. Most historians would bristle at being described as being a historian and writer of fiction, but Professor Balakrishnan in fact has managed to pursue careers as both a scholar as well as an author of fictional works. In fact, the closer we looked, the more it appears that these two seemingly distinct endeavors are quite intertwined. We were intrigued to learn more about Professor Balakrishnan’s journey.]

Elinor Aspegren [EA]: How did you get into writing fiction in addition to academic work? Did one come first?

Sarah Balakrishnan [SB]: My love of fiction started very young. In my earliest yearbook –the 1st grade – I said that I wanted to be a writer when I grow up. That was always the plan. I started out as an English and History major at McGill University, which is where I did my Bachelor’s degree. However, academia pulled me in. I found my History classes interesting, easy, and more creative than the English ones. My professors encouraged me to follow their path to grad school, and before long I was off to pursue my PhD in History at Harvard. But my love of writing never stopped. At Harvard, I took creative writing classes with Claire Messud and Jamaica Kincaid. When I graduated from my PhD in the Spring of 2020, the whole world was in flux, and that allowed me a lot of space to think about what else I wanted to do with my time. Due to the pandemic, my postdoc at the University of Virginia was online. On a whim, I applied to an artist residency at Craigardan, in New York, to work in an all-female writing group for the year with a mentor, Kate Moses. I was accepted to the online residency. From there, everything snowballed. A year and a half later, I had my first fiction publication, I’d won my first award, and I had my wonderful agents, Ellen Levine and Audrey Crooks. In a way, both my careers unfolded at exactly the same time after graduation. In large part, that was because the pandemic, combined with graduation, finally gave me the freedom to write a lot—and to write what I want.

EA: How do you balance your academic writing with your work in fiction writing?

SB: It’s tough to balance two writing careers, involving two very different types of writing. Usually, I go with whatever excites me most. I’m a day-to-day person. If I wake up feeling like writing fiction, I do that. If I’m thinking about history, I work on an academic piece. I write every morning, no exceptions. Sometimes I only have an hour, sometimes two. On a good day, with no meetings, I can write from 8 am until 1 pm without any major interruptions. All my productivity happens before lunch. On a day that I’m not teaching, I can get quite a lot done. Right now I’m working on two books: my first history monograph, which builds off my dissertation, and a collection of short stories that includes some that have already been published. Both of these projects are totally rewarding and exciting. Whenever I feel frustrated with one of the projects, it also really helps to switch to the other. Suddenly, everything feels new and possible again.

EA: Your work on African history centers on how African institutions wield political power. Your work writing fiction focuses on aspirations and relationships, which runs parallel to your academic work in many ways. How does your fiction writing converse with your nonfiction work?

SB: Fundamentally, I am interested in power: how structural relations shape intimate situations, and how certain people are able to gain the upper hand. Both my fiction and academic work explore relationships like this, whether between parents and children, prisoners and prison guards, professors and students, the colonists and the colonized. I want to understand how certain people and processes determine the fate of others, and how those who supposedly have little power can often transform, if not entire upend, their set of circumstances.

In studying Ghanaian history, I have come to believe that the “colonized” always had more power than the “colonizer.” On first glance, that idea seems counterintuitive because colonialism was, of course, a process of political domination. But, by studying why history unfolded the way it did—how the colonial state grew, and changed, and why it eventually toppled—it’s hard for me not see Ghanaians as the ones in charge.

Before colonial rule, Ghanaians had a sophisticated land tenure system that looked a lot like European private property. In fact, Ghanaian lawyers successfully argued to Westminster that their land was private property, and that is what prevented the colonial state from dispossessing the soil. Of all the colonies in Africa, the Gold Coast (today’s southern Ghana) is remarkable because almost 100% of the land remained in African hands. Land was a source of power, which meant that the people were extraordinarily powerful.

In this example, like many that I have studied, the take home message is that every colonial situation is different, just like every relationship is different. To understand the driving force behind history, we have to pay attention to the nuances of power. My stories and my academic work are about these kinds of complex situations, in which social dynamics can change and unfold, and where advantage is often unpredictable.

EA: Your most recent work and upcoming work focuses on how the colonial institutions harnessed mortuary practices for their own imperialist purposes. What got you interested in that topic?

SB: That’s a funny story. When I first started my archival work, I kept coming across reports of colonial police patrolling the cemeteries at night. It was such a strange practice. I had no idea what was going on. Of course, I knew that, before colonial rule, people in the Gold Coast buried their dead in their houses, which was a common practice in Africa. And I imagined that the colonial state probably enforced cemetery burial because home burial seemed unsanitary or gross. But still, to deploy the police this way, and fine people so much for home burial? It all seemed a little crazy.

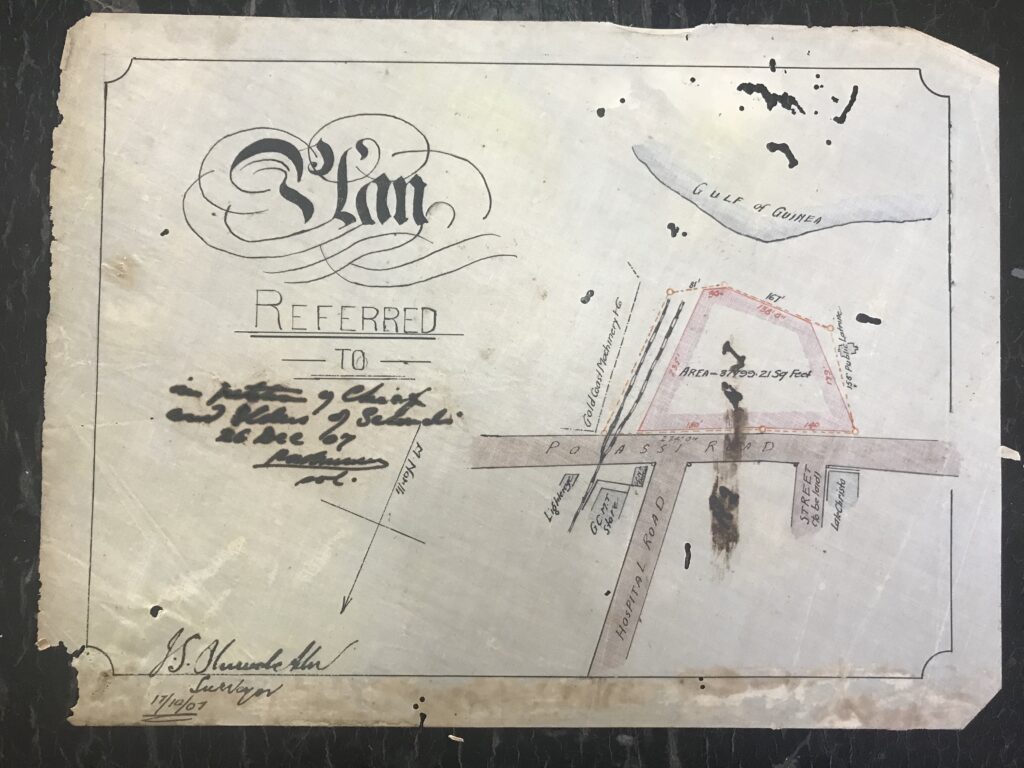

Then, one day, I was working at the National Archives at Kew, and I found a document by a colonial officer complaining that no Gold Coast person would sell their land to the colonial state because the land contained the remains of their elders. And that’s when it all clicked to me. My work on land was tied to the cemeteries! My PhD thesis was about how Gold Coast people dispossessed colonists of their claims to the land by virtue of their sophisticated land tenure system. This meant that the colonial state in Ghana had no rights to the land, and were desperate to buy property. Meanwhile, Gold Coast people would not sell the state their property because it contained the remains of their elders. Colonial cemeteries were invented by a project of desacralizing private land by relocating the ancestors to public community spaces. Public cemeteries helped make private property profane, and therefore, buyable and sellable.

EA: Previously, you concentrated on prisons and policing, before and after colonial rule influenced them. You say on your website that from an African context prisons and policing are a relatively new field of study. How do you do your research, especially in a new field?

SB: My work on prisons comes from another set of unexpected archival finds. When I was working in the public archives in Accra, I kept finding all these letters by female prisoners protesting against the chiefs’ prisons. The letters piqued my interest. The contents seemed so unusual. At the time, I knew enough about prisons in the American context to know that female prisoners were a radical minority. Most inmates, especially in the 19th century, were men. In Ghana, it seemed like the reverse was true. Women were possibly a majority of the prisoners. At that point, I thought to myself: That’s interesting. Maybe one day I will write an article about gender and imprisonment.

[Image: letter picture?]

Only when I started researching these prisons in the secondary literature did I realized that scholars hardly knew anything about the institution. A few articles suggested that the prisons emerged in 1888 because the colonial state had created them. I knew that wasn’t the case because the documents I’d read were well before 1888, and in the context of the colonial state debating whether to ban the institution. So, in other words, these were African prisons, run by African people, and they were imprisoning women, not men. It was such an interesting story, I had to run with it.

It is exciting to be opening the door to a new way of thinking, because that’s what a new field is. In carceral studies, most people today still think that no African society had prisons before colonial rule—that prisons were a uniquely European intervention. It is rewarding to upend that narrative and show that societies in the Global South had, in fact, invented prisons. But it does open a whole new host of questions. If prisons in precolonial Ghana looked so different from those in Europe, what makes them a prison? How do we define “prison” outside its European genealogy? Why would a state imprison women and not men—or, to put it differently, what role do prisons serve in a state’s economy and society? Such a new discovery allows us to return to some of the most fundamental questions as academics, and that’s where I think most of the fun is.

EA: Your work in fiction connects very strongly to current events. But what about your academic work?

SB: When I was staying in Cape Coast, in Ghana, researching in the archives, there was a little market up the hill where I would buy fruit every day. One day, I was picking up some bananas when a group of women surrounded me. They asked me what I was doing in Cape Coast. They were very friendly, joking with me, and laughed loudly when I told them that I worked down in the junction. The national archives are located behind a gas station at the junction, which is what the women thought I meant. When I clarified I worked at the archives, the laughter immediately died. Everyone turned serious. “That place deals in land,” one woman said to me.

That is how most Ghanaian people think about the role of the national archives in their lives. Because the colonial state never had public rights to the land in colonial Ghana, they had no financial incentive to undergo the expensive cadastral surveys conducted in other colonial cities. There was never a map made of all the property holdings in Ghanaian cities. People died not receive land titles from the state. Instead, they could voluntarily register their property in a Land Registry, but this meant nothing legally except their own testimony that they owned something.

Today, land disputes in Ghana are still adjudicated by people going into the archives to find any evidence that their ancestors once owned a piece land. The archives are a place that deal with land disputes. My research tells us why that’s the case, and what the long prehistory is. So, in that way, I think my research is profoundly shaped by current political dynamics.

EA: What’s next for you? What are you writing about in fiction or in academia?

SB: Next are the books! My two books are currently running a race to see who finishes first, and I can’t guess who the winner will be. Book Project 1 is my academic monograph, which analyzes the imperial encounter in Southern Ghana through changes to land, space, and political economy from approximately 1481 to 1957. Book Project 2 is a collection of short stories, loosely cohering around the themes of race, gender, and the intimate lives of men and women. Both projects are about 50% complete right now, though lately I’ve been making more progress on the academic monograph. That’s probably inspired by being back in the classroom this semester, and attending academic conferences in person for the first time in years. I strongly suspect, though, that the upcoming winter holiday will give me more time to write fiction, which always feels so rewarding.